Indian Art from Indus Valley to India Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symbolism of Woman and Tree Motif in Ancient Indian Sculptural Art with Special Reference to Yaksi Figures

International Journal of Applied Social Science RESEARCH PAPER Volume 6 (1), January (2019) : 160-165 ISSN : 2394-1405 Received : 17.11.2018; Revised : 02.12.2018; Accepted : 18.12.2018 Symbolism of Woman and Tree Motif in Ancient Indian Sculptural Art with Special Reference to Yaksi Figures ADITI JAIN Assistant Professor P.G. Department of Fine Arts, BBK DAV College for Women, Amritsar (Punjab) India ABSTRACT Tree worship has always been the earliest and the most prevalent form of religion since ages. Through the worship of nature and trees it became possible for man to approach and believe in god. In India tree worship was common even in the third or fourth millennium B.C. Among the seals of Mohenjo-daro dating from the third or fourth millennium B.C., is one depicting a stylized pipal tree with two heads of unicorns emerging from its stem which proves that tree worship was already being followed even before the rise of Buddhism. The trees were regarded as beneficent devatas because they were the only friends of man is case of any environmental danger. Buddhism adopted the cult of tree worship from the older religions which prevailed in the country. The particular trees which are sal, asoka and plaksha. Gautama achieved enlightenment under a pipal tree which was hence forth called the Bodhi tree, and he died in a grove of sal trees. It was on account of these associations with the Buddha that the trees were regarded as sacred by the Indians. The most important concept of tree worship also reminds us of the worship of a woman especially yaksi or queen Mahamaya associated with the birth of Bodhisattava in a sal grove while holding a branch of sal tree. -

247 Medieval Devanganas : Their Individual Motif

247 CHAPTER - VI DEVANGANA SCULPTURAL IMAGE STUDY PART-II - POST GUPTA AND MEDIEVAL DEVANGANAS : THEIR INDIVIDUAL MOTIF ANALYSIS 1. SVASTANASPARSA 2. KESHANISTOYAKARINI 3. PUTRAVALLABHA 4. KANDUKAKRIDA 5. VASANABHRAMSA 6. MARKATACESTA 7. VIRA 8. DARPANA 9. PRASADHIKA 10. ALASA 11. NATI-NARTAKI 12. NUPURAPADIKA-SANGITAVADINI 248 CHAPTER - VI DEVANGANA SCULPTURE IMAGE STUDY PART - II : VI. 1 POST GUPTA AND MEDIEVAL DEVANGANAS : THEIR INDIVIDUAL MOTIF ANALYSIS 13 The overlapping of meaning in the imageries of Salabhanjika, nadi devis, nayika-kutilaka group, mithunas, aquatic motifs, varuna etc.j implicit in their representation on religious architecture now lead us to the study of individual devangana imageries. In doing so our attention will focus on their varied representations and the contexts in which they have been placed on temple architecture. The aquatic connection emerges as major connecting link between the graceful imageries of celestial womeni often interpreted by scholars as representations of nayikas in stages of love and exhibiting their charms. Often looked at by scholars as apsaras, those infamous alluring 1 snarelike characters of the puranas, who when depicted on the temples^ perform their graceful charms on the spectators. The antithesis between woman and wisdom, sorrow lurking behind the sensual; are observed by some as the reasons why the so called apsaras are carved in profusion on the temple walls. This does not appear convincing. The intention with which I have built up the base, bridging the Salabhanjika, yaksini, nadidevis and apsaras, is to unravel the more chthonfc level of meaning which can be traced back to the Vedic sources. The presence of the woman is ever auspicious and protective, her nourishing aspect and the sensual aspect fuse together or imply fertility, and these concepts have remained in the Indian human psyche 249 perenninally, It is only the contemporary representation which changes the form and hence,? Khajuraho devanganas appear over sensuous than Jaga"t or Matnura yaksis. -

Post Mauryan Trends in Indian Art and Architecture (Indian Culture Series – NCERT)

Post Mauryan Trends in Indian Art and Architecture (Indian Culture Series – NCERT) In this article, we are dealing with the trends in the post-Mauryan art and architecture as a part of the Indian Culture series based on the NCERT textbook ‘An Introduction to Indian Art’- Part 1. We have already discussed the arts of the Mauryan period in the previous article. This post gives a detailed description about the Post-Mauryan Schools of Art and Architecture such as Gandhara, Mathura, Amaravati, etc. and also the cave traditions that existed during the period. This post also deals with some of the important architectural sites such as Sanchi, Ajanta, Ellora, etc. Take the Clear IAS Exam UPSC prelims mock test on Indian culture. You not only will learn the important facts related to Indian culture, but will also start to love the subject! Indian Architecture after the Mauryan Period From the second century BCE onwards, various rulers established their control over the vast Mauryan Empire: the Shungas, Kanvas, Kushanas and Guptas in the north and parts of central India; the Satavahanas, Ikshavakus, Abhiras, Vatakas in southern and western India. The period also marked the rise of the main Brahmanical sects such as the Vaishnavas and Shaivas. Places where important sculptures are seen Some of the finest sculptures of this period are found at Vidisha, Barhut (M.P), Bodhgaya (Bihar), Jaggaypetta (Andhra Pradesh), Mathura (UP), Khandagiri-Udayagiri (Odisha), Bhaja near Pune (Maharashtra). Barhut Barhut sculptures are tall like the images of Yaksha and Yakshini in the Mauryan period. Modelling of the sculpture volume is in low relief maintaining linearity. -

Aspects of Ancient Indian Art and Architecture

ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE M.A. History Semester - I MAHIS - 101 SHRI VENKATESHWARA UNIVERSITY UTTAR PRADESH-244236 BOARD OF STUDIES Prof (Dr.) P.K.Bharti Vice Chancellor Dr. Rajesh Singh Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. S.K.Bhogal, Professor Dr. Yogeshwar Prasad Sharma, Professor Dr. Uma Mishra, Asst. Professor COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Shakeel Kausar Dy. Registrar Author: Dr. Vedbrat Tiwari, Assistant Professor, Department of History, College of Vocational Studies, University of Delhi Copyright © Author, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 -

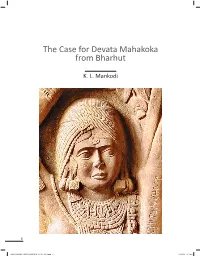

The Case for Devata Mahakoka from Bharhut

The Case for Devata Mahakoka from Bharhut K. L. Mankodi 6 FINAL DUMMY CSMVS JOURNAL 16_06_2016.indd 6 17/06/16 8:17 pm IT is assumed that everything worth 10, H. Lűders listed all the Bharhut inscriptions then known knowing about the ancient Buddhist Stupa of Bharhut has in Epigraphia Indica X.1 In the 1940s, during British rule, the already been published and is easily available. For, did not Archaeological Survey of India had proposed a publication Alexander Cunningham, pioneer of Archaeological Survey by Lűders which would present a revised version of of India, who discovered the great site nearly one hundred Cunningham’s original readings of the inscriptions from and forty years ago, himself give an exhaustive description Bharhut. Unfortunately, this project did not materialise. of it together with illustrations of hundreds of remains Later, in 1963, the Archaeological Survey of India published as early as 1879? And did not Cunningham himself, and Bharhut Inscriptions edited by Lűders and revised by E. thereafter Heinrich Lűders, followed by Ernst Waldschmidt Waldschmidt and M. A. Mehendale.2 In between, other and M. A. Mehendale, re-edit and revise the hundreds of books and articles by B. M. Barua-Gangananda Sinha, and inscriptions that Bharhut had yielded? by S. C. Kala have appeared on the subject. For this paper, references to Cunningham and Lűders-Waldschmidt- Mehendale will suffice. Bharhut: discovery and documentation Cunningham, in his explorations in central India during Devata Chulakoka 1873 came across the remains of the ancient stupa at the One sculpture recovered from the ruins and now in the village of Bharhut, twenty kilometres to the south of the Indian Museum bears the inscription Chulakoka Devata, present district headquarters of Satna in Madhya Pradesh the Sanskrit form of which would be Kshudrakoka Devata. -

285 FOOTNOTES and REFERENCES 1. Kanwar Lai, Erotic

285 CHAPTER-VI DEVANGANA SCULPTURAL IMAGE STUDY PART-II - POST GUPTA AND MEDIEVAL DEVANGANAS - THEIR INDIVIDUAL MOTIF ANALYSIS FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES 1. Kanwar Lai, Erotic Sculptures of Khajuraho, Delhi, 1970, p.24-30. 2. Dr. V.G.Navangule, Lecturef^ Dept, of Art History & Aesthetics, Faculty of Fine Arts^ has helped me to formulate the terms and translation of some verses. 3. M.G.P. Srivastava, Mother Goddess in Indian Art, Archaeology and Literature, New Delhi, 1979, p.51-52. 4. ibid, O.C.Ganguli, IHQ, Vol.XIX, No.l, March, 1943, p.10. 5. O.C.Ganguli, ibid. 6. - Stella Kramrisch, in Khajuraho, Marg Publication. 7. K.S.Shrinivasan, op.cit, 1985, p.20. 8. Kalidasa, The Loom of Time, A Selection of His Plays and Poems, C&andra Rajan, Calcutta, 1989, p.124-128. 9. Subhasita Ratnakosa, K.S.Srinivasan^op. cit, 1985, p.12. 10. H.H.Ingalls, Subhasita Ratnakosa, 1965, op.cit. p.213 11. V.S.Agrawala, op.cit. p.227. 12. U.N.Roy, op.cit. Salabhanjika, 1979, p.22-23 13. V. Raghavan, Uparupakas and Nritya Prabandha^Sangeeta Natak, p.21. 14. The term Mar kata chesta has been formulated after consultation with Dr. V. G. Navangule. 15. T.A.Gopinath Rao, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol.II, Varanasi, 1971, p.568. 16. V.S.Agrawala, op.cit, p.228. 17. Kalidasa, Loom of Time, op.cit. 286 18. ibid. 19. Kalipa Vatsyayan, Classical Dance in Literature and the Arts, New Delhi, 1968, has amply demonstrated this! chapter IV - Sculpture and Dancing. 20. V. -

A Survey of Stone Sculptures from Sanghol

Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design, (ISSN 2231-4822), Vol. 6, No. 1, 2016 Eds. Sreecheta Mukherjee & Tarun Tapas Mukherjee URL of the Issue: www.chitrolekha.com/v6n1 Available at www.chitrolekha.com/V6/n1/05_sculptors_anghol.pdf Kolkata, India. © AesthetixMS Included in Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOHOST, Google Scholar, WorldCat etc. Embodiment of Beauty in Stone: A Survey of Stone Sculptures from Sanghol Ardhendu Ray Independent Researcher Introduction Sanghol, consisting of a group of high ancient mounds, locally known as Ucha Pind, is located in the tahsil Khamanon, district Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab. It lies at a distance of 40 km of the west of Chandigarh on Chandigarh-Ludhiana road and is at a distance of 32 km from Ropar. According to the local tradition, Sanghol was formerly known as ‘Sangaladvīpa’, and the folk tale of Rup Basant was associated with it like Ropar. The present name might have been derived from Saṅghapura, a name which may have been given for its being a stronghold of Buddhist congregation or Saṅgha.1 A terracotta clay Sealing with Gupta Brāhmī legend discovered from Sanghol mentions the name ‘Nandipurasya’ and carries a representation of a bull to right above. Some scholars interpreted this as the evidence of Sanghol was known as Nandipura in the 5th century CE.2 The river Sutlej once flowing by the side of the village but now it has shifted to a distance of about 10 km. The results of excavation and explorations of this site have provided evidence of continued habitation at this site from 2000 BCE to modern times with short breaks in between. -

Bulletin of Tibetology

6th NOVEMBER. 1914 PR.INTED BY THE MANAGBIl. SIJ(KIM GOVEIlMNENT PREIS AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, NAMGY AL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK , ' SIR TASHI NAMGYAL MEMORIAL LECTURES 1974 BUDDHIST ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN INDIA AND NEPAL By KRISHNA DEVA ARCHAEOLOGICAL ADVISER INDIAN COOPERATION MISSION KATHMANDU (NEPAL) CONTINI'S Pages I. Buddhist Art in India 5 II. Buddhist Architecture in India 12 III. Buddhist Art in Nepal 29 IV. Buddhist Architecture in Nepal 46 PREFACIL I am indeed grateful to the Chogyal of Sikkim and Dr. A.M. 0' Rozario, the Pre~ident and Director rei>pectively of the N;:mgyd lf1stAfute of Tibetology, for h<,ving invited me to deliver the 1974 Sir Tashi Namgyal Memorial Lectures. I have been a stmknt c,f Indian art and archItecture including Buddhist art during my long senice with the Archa.eologicd Survey Jt/india and have als(l <;tudied the art and architect me oj NepJ during the last ten years and more intensively during the lest two years as l\r,~haeological Ad,:i~er to His Majesty's Government of Nepal. Nepal has been open to the artistic and religious influences fl( wing from her great southern neighbour India. and her great northei n neighbour Tibet and has had tire genius to' (so catalyse these inflm ncf' that her at and culture have become truly Nepali. Sikkim h~,.s like wise ben' ( Fen to the cultur<ll, religious and artistic impacts coming fn-.m not only India and Tibet but also from Nepal and has similarly had the genius to assimilate them into her culture. -

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art

Rienjang and Stewart (eds) Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Since the beginning of Gandhāran studies in the nineteenth century, chronology has been one of the most significant challenges to the understanding of Gandhāran art. Many other ancient societies, including those of Greece and Rome, have left a wealth of textual sources which have put their fundamental chronological frameworks beyond doubt. In the absence of such sources on a similar scale, even the historical eras cited on inscribed Gandhāran works of art have been hard to place. Few sculptures have such inscriptions and the majority lack any record of find-spot or even general provenance. Those known to have been found at particular sites were sometimes moved and reused in antiquity. Consequently, the provisional dates assigned to extant Gandhāran sculptures have sometimes differed by centuries, while the narrative of artistic development remains doubtful and inconsistent. Building upon the most recent, cross-disciplinary research, debate and excavation, this volume reinforces a new consensus about the chronology of Gandhāra, bringing the history of Gandhāran art into sharper focus than ever. By considering this tradition in its wider context, alongside contemporary Indian art and subsequent developments in Central Asia, the authors also open up fresh questions and problems which a new phase of research will need to address. Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art is the first publication of the Gandhāra Connections project at the University of Oxford’s Classical Art Research Centre, which has been supported by the Bagri Foundation and the Neil Kreitman Foundation. -

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art

Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017 Edited by Wannaporn Rienjang Peter Stewart Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 855 2 ISBN 978 1 78491 856 9 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Acknowledgements ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Note on orthography ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Contributors �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 1 Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart Numismatic evidence and the date of Kaniṣka I ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 Joe Cribb -

SCULPTURES • • • Allahabad Municipal Museum • S

SCULPTURES • • • Allahabad Municipal Museum • S. C. KALA KITABISTAN '~'...vtures in the Allahabad unic~pal Mruseum By SATISH CHANDRA KALA, M.A. CURATOR ALLAHABAD MUNICIPALม MUSEUM ำนกั หอส ุดกลาง ส KITABISTAN ALLAHABAD MUNSHI RAM 1'1; & j Orientnl Fmc. , ~en.. P.B. 1165. Nai :;,,' D'::.LEl-r.. • FOREWORD Allahabad, at the junction of the Ganges and the Jumna, is one of the nodal points in. the geography, the history and doubtless the prehistory of the great northern plains of India. It is fitting, indeed necessary, therefore, that the city should possess a Museum, and inevitable that this, with lively direction, should rapidly accumulate material of outstanding range and quality. The present Museum is still a young one butกั alreadyหอ containsสมุด muchกล าof essential value. Next to registration and arrangement,สำน the most important task งconfronting the Cura tor is that of publication, and I have accordingly a special pleasure in blessing this, the first guide to a part of the collections under Mr. Kala's charge. It is particularly encouraging to note.,.. that the Museum itself is not a product of the "Government Machine" but is primarily the result of the wise enthusiasm of two citizens of Allahabad. May it prosper. SIMLA R. M. WHEELER September 1945 Director General of Archr.eology in India 3 • PREFACE This monograph is intended to serve a double purpose. Firstly, it will be a special guide to the Sculpture section of the Allahabad Municipal Museum and secondly, it will introduce to scholars and art critics some hitherto unknown specimens of Indian Sculpture. I have made an honest effort to identify and discuss the sculptures and deliberately refrained from drawing dogmatic con clusions. -

Renaud Montméat a R T D ' a S

renaud montméat artd’asie 36, rue étienne marcel 75002 paris montmeat-asianart.com Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art renaud montméat artd’asie 36, rue étienne marcel 75002 paris +33 6 17 61 21 60 [email protected] montmeat-asianart.com MAITREYA Grey schist Height: 60 cm 3rd century AD Pakistan, Ancient region of Gandhara Provenance: French diplomat collection, 1950-60’s Art Loss Register Certificate: S00120100 Unlike the Buddha represented dressed with the monastic robes, the Gandharan Bodhisattvas wear the sumptuous classical clothes of north Indian princes of the Kusana period. Here, Maitreya is adorned with a wide torque, elaborate necklaces, a string of amulets and floral armlets. His long hair is fastened into two loops on top of his head. The lower arms are missing but typically Maitreya holds a kundika or water flask in the left hand and his right hand is in abhaya mudra. Bodhisattva is the second most popular image in Gandharan Buddhist art after Buddha himself, revealing a shift in Buddhist practice that emphasized the veneration of bodhisattvas. In Mahayana Buddhism, this saintly being is capable of achieving enlightenment and thus saving himself from the cycle of rebirth, voluntarily renounces Nirvana in order to help others find the right path to salvation. For a very similar Maitreya see: Kurt A. Behrendt, The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. p. 54, Cat. 42. MANJUSHRI Bronze Height: 20,5 cm 9th century Central Java Provenance: Private collection, USA Marcel Nies Oriental Art, Antwerpen, Belgium, 2013 Art Loss Register Certificate: S00070163 Registered in the documentation Centre for Ancient Indonesian Art, Amsterdam.