TS Art of India 4C.Qxp 7/6/2010 9:06 AM Page 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symbolism of Woman and Tree Motif in Ancient Indian Sculptural Art with Special Reference to Yaksi Figures

International Journal of Applied Social Science RESEARCH PAPER Volume 6 (1), January (2019) : 160-165 ISSN : 2394-1405 Received : 17.11.2018; Revised : 02.12.2018; Accepted : 18.12.2018 Symbolism of Woman and Tree Motif in Ancient Indian Sculptural Art with Special Reference to Yaksi Figures ADITI JAIN Assistant Professor P.G. Department of Fine Arts, BBK DAV College for Women, Amritsar (Punjab) India ABSTRACT Tree worship has always been the earliest and the most prevalent form of religion since ages. Through the worship of nature and trees it became possible for man to approach and believe in god. In India tree worship was common even in the third or fourth millennium B.C. Among the seals of Mohenjo-daro dating from the third or fourth millennium B.C., is one depicting a stylized pipal tree with two heads of unicorns emerging from its stem which proves that tree worship was already being followed even before the rise of Buddhism. The trees were regarded as beneficent devatas because they were the only friends of man is case of any environmental danger. Buddhism adopted the cult of tree worship from the older religions which prevailed in the country. The particular trees which are sal, asoka and plaksha. Gautama achieved enlightenment under a pipal tree which was hence forth called the Bodhi tree, and he died in a grove of sal trees. It was on account of these associations with the Buddha that the trees were regarded as sacred by the Indians. The most important concept of tree worship also reminds us of the worship of a woman especially yaksi or queen Mahamaya associated with the birth of Bodhisattava in a sal grove while holding a branch of sal tree. -

Trends in Indian Historiography

HIS2B02 - TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY SEMESTER II Core Course BA HISTORY CBCSSUG (2019) (2019 Admissions Onwards) School of Distance Education University of Calicut HIS2 B02 Trends in Indian Hstoriography University of Calicut School of Distance Education Study Material B.A.HISTORY II SEMESTER CBCSSUG (2019 Admissions Onwards) HIS2B02 TRENDS IN INDIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY Prepared by: Module I & II :Dr. Ancy. M. A Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Module III & IV : Vivek. A. B Assistant Professor School of Distance Education University of Calicut. Scrutinized by : Dr.V V Haridas, Associate Professor, Dept. of History, University of Calicut. MODULE I Historical Consciousness in Pre-British India Jain and Bhuddhist tradition Condition of Hindu Society before Buddha Buddhism is centered upon the life and teachings of Gautama Buddha, where as Jainism is centered on the life and teachings of Mahavira. Both Buddhism and Jainism believe in the concept of karma as a binding force responsible for the suffering of beings upon earth. One of the common features of Bhuddhism and jainism is the organisation of monastic orders or communities of Monks. Buddhism is a polytheistic religion. Its main goal is to gain enlightenment. Jainism is also polytheistic religion and its goals are based on non-violence and liberation the soul. The Vedic idea of the divine power of speech was developed into the philosophical concept of hymn as the human expression of the etheric vibrations which permeate space and which were first knowable cause of creation itself. Jainism and Buddhism which were instrumental in bringing about lot of changes in the social life and culture of India. -

July-September 2016, Volume 18 No. 1

DIALOGUE QUARTERLY Volume-18 No. 1 July-September, 2016 Subscription Rates : For Individuals (in India) Single issue Rs. 30.00 Annual Rs. 100.00 For 3 years Rs. 250.00 For Institutions: Single Issue Rs. 60.00 in India, Abroad US $ 15 Annual Rs. 200.00 in India, Abroad US $ 50 For 3 years Rs. 500.00 in India, Abroad US $ 125 All cheques and Bank Drafts (Account Payee) are to be made in the name of “ASTHA BHARATI”, Delhi. Advertisement Rates : Outside back-cover Rs. 25, 000.00 Per issue Inside Covers Rs. 20, 000.00 ,, Inner page coloured Rs. 15, 000.00 ,, Inner full page Rs. 10, 000.00 ,, DIALOGUE QUARTERLY Editorial Advisory Board Mrinal Miri Jayanta Madhab Editor B.B. Kumar Consulting Editor J.N. Roy ASTHA BHARATI DELHI The views expressed by the contributors do not necessarily represent the view-point of the journal. © Astha Bharati, New Delhi Printed and Published by Dr. Lata Singh, IAS (Retd.) Secretary, Astha Bharati Registered Office: 27/201 East End Apartments, Mayur Vihar, Phase-I Extension, Delhi-110096. Working Office: 23/203 East End Apartments, Mayur Vihar, Phase-I Extension, Delhi-110096 Phone : 91-11-22712454 e-mail : [email protected] web-site : www. asthabharati.org Printed at : Nagri Printers, Naveen Shahdara, Delhi-32 Contents Editorial Perspective 7 Intellectual mercenaries, the Post-Independence Avataras of the Hindu Munshis 1. North-East Scan Assam Floods: Another Perspective 11 Patricia Mukhim Manipur: Maintaining Sanity in the Times of Chaos 14 Pradip Phanjoubam 2. Pre-Paninian India Linguistic Awareness from Rig Veda to Mahabharata 17 Dr. -

247 Medieval Devanganas : Their Individual Motif

247 CHAPTER - VI DEVANGANA SCULPTURAL IMAGE STUDY PART-II - POST GUPTA AND MEDIEVAL DEVANGANAS : THEIR INDIVIDUAL MOTIF ANALYSIS 1. SVASTANASPARSA 2. KESHANISTOYAKARINI 3. PUTRAVALLABHA 4. KANDUKAKRIDA 5. VASANABHRAMSA 6. MARKATACESTA 7. VIRA 8. DARPANA 9. PRASADHIKA 10. ALASA 11. NATI-NARTAKI 12. NUPURAPADIKA-SANGITAVADINI 248 CHAPTER - VI DEVANGANA SCULPTURE IMAGE STUDY PART - II : VI. 1 POST GUPTA AND MEDIEVAL DEVANGANAS : THEIR INDIVIDUAL MOTIF ANALYSIS 13 The overlapping of meaning in the imageries of Salabhanjika, nadi devis, nayika-kutilaka group, mithunas, aquatic motifs, varuna etc.j implicit in their representation on religious architecture now lead us to the study of individual devangana imageries. In doing so our attention will focus on their varied representations and the contexts in which they have been placed on temple architecture. The aquatic connection emerges as major connecting link between the graceful imageries of celestial womeni often interpreted by scholars as representations of nayikas in stages of love and exhibiting their charms. Often looked at by scholars as apsaras, those infamous alluring 1 snarelike characters of the puranas, who when depicted on the temples^ perform their graceful charms on the spectators. The antithesis between woman and wisdom, sorrow lurking behind the sensual; are observed by some as the reasons why the so called apsaras are carved in profusion on the temple walls. This does not appear convincing. The intention with which I have built up the base, bridging the Salabhanjika, yaksini, nadidevis and apsaras, is to unravel the more chthonfc level of meaning which can be traced back to the Vedic sources. The presence of the woman is ever auspicious and protective, her nourishing aspect and the sensual aspect fuse together or imply fertility, and these concepts have remained in the Indian human psyche 249 perenninally, It is only the contemporary representation which changes the form and hence,? Khajuraho devanganas appear over sensuous than Jaga"t or Matnura yaksis. -

Post Mauryan Trends in Indian Art and Architecture (Indian Culture Series – NCERT)

Post Mauryan Trends in Indian Art and Architecture (Indian Culture Series – NCERT) In this article, we are dealing with the trends in the post-Mauryan art and architecture as a part of the Indian Culture series based on the NCERT textbook ‘An Introduction to Indian Art’- Part 1. We have already discussed the arts of the Mauryan period in the previous article. This post gives a detailed description about the Post-Mauryan Schools of Art and Architecture such as Gandhara, Mathura, Amaravati, etc. and also the cave traditions that existed during the period. This post also deals with some of the important architectural sites such as Sanchi, Ajanta, Ellora, etc. Take the Clear IAS Exam UPSC prelims mock test on Indian culture. You not only will learn the important facts related to Indian culture, but will also start to love the subject! Indian Architecture after the Mauryan Period From the second century BCE onwards, various rulers established their control over the vast Mauryan Empire: the Shungas, Kanvas, Kushanas and Guptas in the north and parts of central India; the Satavahanas, Ikshavakus, Abhiras, Vatakas in southern and western India. The period also marked the rise of the main Brahmanical sects such as the Vaishnavas and Shaivas. Places where important sculptures are seen Some of the finest sculptures of this period are found at Vidisha, Barhut (M.P), Bodhgaya (Bihar), Jaggaypetta (Andhra Pradesh), Mathura (UP), Khandagiri-Udayagiri (Odisha), Bhaja near Pune (Maharashtra). Barhut Barhut sculptures are tall like the images of Yaksha and Yakshini in the Mauryan period. Modelling of the sculpture volume is in low relief maintaining linearity. -

Aspects of Ancient Indian Art and Architecture

ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE M.A. History Semester - I MAHIS - 101 SHRI VENKATESHWARA UNIVERSITY UTTAR PRADESH-244236 BOARD OF STUDIES Prof (Dr.) P.K.Bharti Vice Chancellor Dr. Rajesh Singh Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. S.K.Bhogal, Professor Dr. Yogeshwar Prasad Sharma, Professor Dr. Uma Mishra, Asst. Professor COURSE CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Shakeel Kausar Dy. Registrar Author: Dr. Vedbrat Tiwari, Assistant Professor, Department of History, College of Vocational Studies, University of Delhi Copyright © Author, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 -

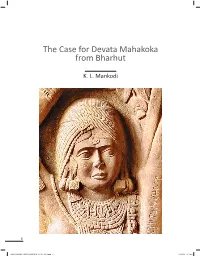

The Case for Devata Mahakoka from Bharhut

The Case for Devata Mahakoka from Bharhut K. L. Mankodi 6 FINAL DUMMY CSMVS JOURNAL 16_06_2016.indd 6 17/06/16 8:17 pm IT is assumed that everything worth 10, H. Lűders listed all the Bharhut inscriptions then known knowing about the ancient Buddhist Stupa of Bharhut has in Epigraphia Indica X.1 In the 1940s, during British rule, the already been published and is easily available. For, did not Archaeological Survey of India had proposed a publication Alexander Cunningham, pioneer of Archaeological Survey by Lűders which would present a revised version of of India, who discovered the great site nearly one hundred Cunningham’s original readings of the inscriptions from and forty years ago, himself give an exhaustive description Bharhut. Unfortunately, this project did not materialise. of it together with illustrations of hundreds of remains Later, in 1963, the Archaeological Survey of India published as early as 1879? And did not Cunningham himself, and Bharhut Inscriptions edited by Lűders and revised by E. thereafter Heinrich Lűders, followed by Ernst Waldschmidt Waldschmidt and M. A. Mehendale.2 In between, other and M. A. Mehendale, re-edit and revise the hundreds of books and articles by B. M. Barua-Gangananda Sinha, and inscriptions that Bharhut had yielded? by S. C. Kala have appeared on the subject. For this paper, references to Cunningham and Lűders-Waldschmidt- Mehendale will suffice. Bharhut: discovery and documentation Cunningham, in his explorations in central India during Devata Chulakoka 1873 came across the remains of the ancient stupa at the One sculpture recovered from the ruins and now in the village of Bharhut, twenty kilometres to the south of the Indian Museum bears the inscription Chulakoka Devata, present district headquarters of Satna in Madhya Pradesh the Sanskrit form of which would be Kshudrakoka Devata. -

Model Test Paper-1

MODEL TEST PAPER-1 No. of Questions: 120 Time: 2 hours Codes: I II III IV (a) A B C D Instructions: (b) C A B D (c) A C D B (A) All questions carry equal marks (d) C A D B (B) Do not waste your time on any particular question 4. Where do we find the three phases, viz. Paleolithic, (C) Mark your answer clearly and if you want to change Mesolithic and Neolithic Cultures in sequence? your answer, erase your previous answer completely. (a) Kashmir Valley (b) Godavari Valley (c) Belan Valley (d) Krishna Valley 1. Pot-making, a technique of great significance 5. Excellent cave paintings of Mesolithic Age are found in human history, appeared first in a few areas at: during: (a) Bhimbetka (b) Atranjikhera (a) Early Stone Age (b) Middle Stone Age (c) Mahisadal (d) Barudih (c) Upper Stone Age (d) Late Stone Age 6. In the upper Ganga valley iron is first found associated 2. Which one of the following pairs of Palaeolithic sites with and areas is not correct? (a) Black-and-Red Ware (a) Didwana—Western Rajasthan (b) Ochre Coloured Ware (b) Sanganakallu—Karnataka (c) Painted Grey Ware (c) Uttarabaini—Jammu (d) Northern Black Polished Ware (d) Riwat—Pakistani Punjab 7. Teri sites, associated with dunes of reddened sand, 3. Match List I with List II and select the answer from are found in: the codes given below the lists: (a) Assam (b) Madhya Pradesh List I List II (c) Tamil Nadu (d) Andhra Pradesh Chalcolithic Cultures Type Sites 8. -

285 FOOTNOTES and REFERENCES 1. Kanwar Lai, Erotic

285 CHAPTER-VI DEVANGANA SCULPTURAL IMAGE STUDY PART-II - POST GUPTA AND MEDIEVAL DEVANGANAS - THEIR INDIVIDUAL MOTIF ANALYSIS FOOTNOTES AND REFERENCES 1. Kanwar Lai, Erotic Sculptures of Khajuraho, Delhi, 1970, p.24-30. 2. Dr. V.G.Navangule, Lecturef^ Dept, of Art History & Aesthetics, Faculty of Fine Arts^ has helped me to formulate the terms and translation of some verses. 3. M.G.P. Srivastava, Mother Goddess in Indian Art, Archaeology and Literature, New Delhi, 1979, p.51-52. 4. ibid, O.C.Ganguli, IHQ, Vol.XIX, No.l, March, 1943, p.10. 5. O.C.Ganguli, ibid. 6. - Stella Kramrisch, in Khajuraho, Marg Publication. 7. K.S.Shrinivasan, op.cit, 1985, p.20. 8. Kalidasa, The Loom of Time, A Selection of His Plays and Poems, C&andra Rajan, Calcutta, 1989, p.124-128. 9. Subhasita Ratnakosa, K.S.Srinivasan^op. cit, 1985, p.12. 10. H.H.Ingalls, Subhasita Ratnakosa, 1965, op.cit. p.213 11. V.S.Agrawala, op.cit. p.227. 12. U.N.Roy, op.cit. Salabhanjika, 1979, p.22-23 13. V. Raghavan, Uparupakas and Nritya Prabandha^Sangeeta Natak, p.21. 14. The term Mar kata chesta has been formulated after consultation with Dr. V. G. Navangule. 15. T.A.Gopinath Rao, Elements of Hindu Iconography, Vol.II, Varanasi, 1971, p.568. 16. V.S.Agrawala, op.cit, p.228. 17. Kalidasa, Loom of Time, op.cit. 286 18. ibid. 19. Kalipa Vatsyayan, Classical Dance in Literature and the Arts, New Delhi, 1968, has amply demonstrated this! chapter IV - Sculpture and Dancing. 20. V. -

A Survey of Stone Sculptures from Sanghol

Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design, (ISSN 2231-4822), Vol. 6, No. 1, 2016 Eds. Sreecheta Mukherjee & Tarun Tapas Mukherjee URL of the Issue: www.chitrolekha.com/v6n1 Available at www.chitrolekha.com/V6/n1/05_sculptors_anghol.pdf Kolkata, India. © AesthetixMS Included in Art Full Text (H.W. Wilson), EBSCOHOST, Google Scholar, WorldCat etc. Embodiment of Beauty in Stone: A Survey of Stone Sculptures from Sanghol Ardhendu Ray Independent Researcher Introduction Sanghol, consisting of a group of high ancient mounds, locally known as Ucha Pind, is located in the tahsil Khamanon, district Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab. It lies at a distance of 40 km of the west of Chandigarh on Chandigarh-Ludhiana road and is at a distance of 32 km from Ropar. According to the local tradition, Sanghol was formerly known as ‘Sangaladvīpa’, and the folk tale of Rup Basant was associated with it like Ropar. The present name might have been derived from Saṅghapura, a name which may have been given for its being a stronghold of Buddhist congregation or Saṅgha.1 A terracotta clay Sealing with Gupta Brāhmī legend discovered from Sanghol mentions the name ‘Nandipurasya’ and carries a representation of a bull to right above. Some scholars interpreted this as the evidence of Sanghol was known as Nandipura in the 5th century CE.2 The river Sutlej once flowing by the side of the village but now it has shifted to a distance of about 10 km. The results of excavation and explorations of this site have provided evidence of continued habitation at this site from 2000 BCE to modern times with short breaks in between. -

Bulletin of Tibetology

6th NOVEMBER. 1914 PR.INTED BY THE MANAGBIl. SIJ(KIM GOVEIlMNENT PREIS AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, NAMGY AL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK , ' SIR TASHI NAMGYAL MEMORIAL LECTURES 1974 BUDDHIST ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN INDIA AND NEPAL By KRISHNA DEVA ARCHAEOLOGICAL ADVISER INDIAN COOPERATION MISSION KATHMANDU (NEPAL) CONTINI'S Pages I. Buddhist Art in India 5 II. Buddhist Architecture in India 12 III. Buddhist Art in Nepal 29 IV. Buddhist Architecture in Nepal 46 PREFACIL I am indeed grateful to the Chogyal of Sikkim and Dr. A.M. 0' Rozario, the Pre~ident and Director rei>pectively of the N;:mgyd lf1stAfute of Tibetology, for h<,ving invited me to deliver the 1974 Sir Tashi Namgyal Memorial Lectures. I have been a stmknt c,f Indian art and archItecture including Buddhist art during my long senice with the Archa.eologicd Survey Jt/india and have als(l <;tudied the art and architect me oj NepJ during the last ten years and more intensively during the lest two years as l\r,~haeological Ad,:i~er to His Majesty's Government of Nepal. Nepal has been open to the artistic and religious influences fl( wing from her great southern neighbour India. and her great northei n neighbour Tibet and has had tire genius to' (so catalyse these inflm ncf' that her at and culture have become truly Nepali. Sikkim h~,.s like wise ben' ( Fen to the cultur<ll, religious and artistic impacts coming fn-.m not only India and Tibet but also from Nepal and has similarly had the genius to assimilate them into her culture. -

Study Material Ma History – Ii Year Mhi33 – Historiography

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY STUDY MATERIAL MA HISTORY – II YEAR MHI33 – HISTORIOGRAPHY DR. N. DHAIVAMSAM Assistant Professor in History 1 UNIT CONTENT PAGE NO History- Meaning – Definition – Nature and I Scope – Value of History 3 - 12 History and Allied Studies – Types of II History – Whether Science or Art 13 - 21 Genesis and Growth – Greek – Roman Historiography – Medieval Arab III 22 - 31 Historiography French and Marxist Historians – Evolution of Quantitative History – Modernism - Post IV 32 - 40 Modernism. Indian Historiographers – Bana - Kalhana – Ferishta – Barani – Abul Fazl – V A Smith – K.P. Jayaswal – J N Sarkar – DD Kosami – V 41 - 64 K.A. Nilakanta Sasthri, K.K. Pillay – N. Subrahmaniyam. 2 MA HISTORY (II- YEAR) MHI33 - HISTORIOGRAPHY (STUDY MATERIAL) UNIT- I The term historiography refers to a body of historical work on various topics. It also refers to the art and the science of writing history. Historiography may be defined as “The history of history”. Historiography is usually defined and studied by topic, examples being the “Historiography of the French Revolution,” the “Historiography of the Spanish Inquisition,” or the “Historiography of Ancient India". Historiography also encompasses specific approaches and tools employed for the study of history. Introduction: History is the study of life in society in the past, in all its aspect, in relation to present developments and future hopes. It is the story of man in time, an inquiry into the past based on evidence. Indeed, evidence is the raw material of history teaching and learning. It is an Inquiry into what happened in the past, when it happened, and how it happened.