HISTORY of KAKARI GHARI (FOLK MUSIC) 30-46 Muhammad Asif, Prof: Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II

CAPSTONE 20-1 SWA Field Study Trip Book Part II Subject Page Afghanistan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 2 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 3 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 24 Culture Gram .......................................................... 30 Kazakhstan ................................................................ CIA Summary ......................................................... 39 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 40 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 58 Culture Gram .......................................................... 62 Uzbekistan ................................................................. CIA Summary ......................................................... 67 CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 68 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 86 Culture Gram .......................................................... 89 Tajikistan .................................................................... CIA World Fact Book .............................................. 99 BBC Country Profile ............................................... 117 Culture Gram .......................................................... 121 AFGHANISTAN GOVERNMENT ECONOMY Chief of State Economic Overview President of the Islamic Republic of recovering -

Zazai Tribe’ Mean Anything About the Origin of Zaza People? (Zazai Aşireti Zazaların Kökeni Hakkında Bir Şeyler Söyleyebilir Mi?)

Bingöl Üniversitesi Yaşayan Diller Enstitüsü Dergisi Yıl:1, Cilt:1, Sayı:1, Ocak 2015, ss. 115-123 Can ‘Zazai Tribe’ Mean Anything About The Origin Of Zaza People? (Zazai Aşireti Zazaların Kökeni Hakkında Bir Şeyler Söyleyebilir Mi?) Rasim BOZBUĞA1 Abstract The main purpose of this paper is to review bibliography and investigate relevant information about Zazai tribe and Zaza people in order to explore pos- sible connection between them. Findings about Zazas and Zazai Pastun tribe indicate that these two groups have strong connection which is more than ha- ving phonological similar names. Moreover, religious, cultural, historical re- semblances point out that these two groups share some mutual characteristics. Indeed, it is strongly possible that these two groups have originated from same ancestors or same areas (i.e. greater Khorasan or Northern Iran). Keywords : Zazas, Zaza People, The Origin Of The Zazas, Zazai Peshtun Tribe And Zaza Peshtun. Özet Zazai aşiretiyle Zaza halkı arasında ses benzerliği dışında ilişki bulunup bu- lunmadığı sorusunu cevaplamaya çalışan bu çalışmada Zazai aşiretiyle Zaza halkı arasında dilbilimsel, dinsel, kültürel ve yaşam biçimi açısından dikkat çekici benzerliklerin bulunduğu tespit edilmiştir. Zazaca’nın en yakın olduğu dillerden biri olan Partça bazı kelimelerin hem Zazaca’da hem Peştunca’da bulunması, Peştun aşiretlerinden sadece Zazai aşiretiyle soy birliği olan Turi aşiretinin Şii olması, Zazai Attan dansıyla Alevi semahlarının benzer figürleri 1 Gazi Üniversitesi Siyaset Bilimi Doktora Öğrencisi Yıl/Year:1, Cilt/Volume:1, Sayı/Issue:1, Ocak 2015 116 Rasim BOZBUĞA içermesi, Zazai aşiretinin yaşadığı bölgelerin Zazaların yaşadığı coğrafya gibi dağlık alanlar olması, Zazai aşiretinin ataları arasında Zaza-Goran gruplar ara- sında bulunan Kakai adında atanın olması, Zazai aşiretinin içinde bulundugu Karlan grubunun sonradan Peştunlaştığına ilişkin rivayetler Zazai aşiretiyle Zaza/Goran halkının ortak bir coğrafya yada ortak bir soydan gelmiş olabilece- ği varsayımını güçlendirmektedir. -

Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Kabul Times Digitized Newspaper Archives 9-1-1965 Kabul Times (September 1, 1965, vol. 4, no. 130) Bakhtar News Agency Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bakhtar News Agency, "Kabul Times (September 1, 1965, vol. 4, no. 130)" (1965). Kabul Times. 1087. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/kabultimes/1087 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Newspaper Archives at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kabul Times by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ...- . " - ~-;;-4 .;~-. -~ " -:'-' .. .-. - . '. .- '_., .-.. -.- :- .:-;;--'" -- - ' .. " ... : :- :;.... '" ~ • ,-- • '-: •••• :~._. _'i: ;' . -' ... ... '. -' • _'O~ ~ ; .- ;:-:: •• ...;.::••<_:. _...;; .'..-,. .... , '.=: ~ <'..'.:-:'-,:' ..'. ."'- -' .. ::.- .'. .' . .~ ; , ~ ..' " . : ' " ~ - . _::. ....,: . -.. •.. -- - .. ... - -. .-~ . ' . -:.~: ••/. -~ :- -::. ~ ~~- .. -~: -;: <: : . ;.'. ....---- .. " . ".-- .. ... - .: .. "~., ~.-""- . - :.. -.' _.- ':- . ....-. - -.- .. - : .'--..;.. ,:"' -~ •• • ..' • 0- -.. - .. :~ _.~ ~- _.- . -.... .. -' - .- ... ,. -.~.::..:- ~_. - -\ . - .' . _..: - . - _.. - -'. - _. • ·C-. - - - -' . .' ~ ':~NEwS':"ST~S-~",~·."',:C". - ~ - ';. .. .::..~: :..--;- ..... .' -'. yesterday'sTemperamre ' o. ~'~. ' .•.•~" ~b;.I'.~es. is.' ~~hblec 'IJ::~ - -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

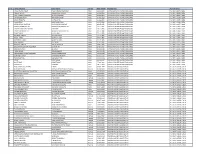

Sl. No. Name of Players Father Name Gender Date of Birth Member Unit

Sl. No. Name of Players Father Name Gender Date of Birth Member Unit PLAYER ID NO 1 VIKAS VISHNU PILLAY PILLAY VISHNU MANIKAM Male 20.11.1989 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00042 / 2013 2 YOUSUF AFFAN MOHAMMED YOUSUF Male 29.12.1994 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00081 / 2013 3 LALIT KUMAR UPADHYAY SATISH UPADHYAY Male 01.12.1993 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 00090 / 2013 4 SHIVENDRA SINGH JHAMMAN SINGH Male 09.06.1983 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01984 / 2014 5 ARJUN HALAPPA B K HALAPPA Male 17.12.1980 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01985 / 2014 6 JOGA SINGH HARJINDER SINGH Male 01.01.1986 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01986 / 2014 7 GIRISH RAVAJI PIMPALE RAVAJI BHIKU PIMPALE Male 06.05.1983 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01987 / 2014 8 VIKRAM VISHNU PILLAY MANIKAM VISHNU PILLAY Male 27.11.1981 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01988 / 2014 9 VINAYA VAKKALIGA SWAMY B SWAMY Male 24.11.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01989 / 2014 10 VINOD VISHNU PILLAY MANIKAM VISHNU PILLAY Male 05.12.1988 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01990 / 2014 11 SAMEER DAD KHUDA DAD Male 25.11.1978 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01991 / 2014 12 PRABODH TIRKEY WALTER TIREKY Male 15.12.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01992 / 2014 13 BIMAL LAKRA MARCUS LAKRA Male 04.05.1980 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD PL / AIR / 01993 / 2014 14 BIRENDAR LAKRA MARCUS LAKRA Male 22.12.1985 AIR INDIA SPORTS PROMOTION BOARD -

Primo.Qxd (Page 1)

daily Vol No. 50 No. 38 JAMMU, SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2014 REGD.NO.JK-71/12-14 16 Pages ` 3.50 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/1992 Omar for benefits of innovations to ‘Aam Aadmi’ Shabir quits, resignation accepted by Governor Vice-President asks Scientists to be Police summons ex-Minister Minister acted like a sexual cognizant of social, ethical imperatives through SSP Jammu Nishikant Khajuria on conclusion of the 101st physics, space technology etc predator: Doctor Indian Science Congress, here have transformed our world as JAMMU, Feb 7: The five- today in the presence of Chief never before but at the same *Ministry strength down to 24 Fayaz Bukhari day Indian Science Congress Minister Omar Abdullah, time also carry with them con- arrested as soon as he appeared before in Jammu University conclud- Governor N N Vohra, Union siderable social and ethical Sanjeev Pargal SRINAGAR, Feb 7: The separatist leader's wife, on whose complaint the police. ed amid a call from Vice- Minister Farooq Abdullah and implications, which must be police have registered a case against former Minister of State for Health, “Let us see. If he didn't appear, only President Mohammad others. addressed,” he said adding that JAMMU, Feb 7: Minister of State Shabir Ahmad Khan, alleged that Minister acted like a sexual predator. then we will initiate other legal courses Hamid Ansari to the Scientists Expressing his concern over impact of social media networks for Health (Independent Charge) The doctor in her complaint alleges: "The Minister acted like sexual predator. I of action,'' -

Taliban Militancy: Replacing a Culture of Peace

Taliban Militancy: Replacing a culture of Peace Taliban Militancy: Replacing a culture of Peace * Shaheen Buneri Abstract Time and again Pashtun leadership in Afghanistan and Pakistan has demanded for Pashtuns' unity, which however until now is just a dream. Violent incidents and terrorist attacks over the last one decade are the manifestation of an intolerant ideology. With the gradual radicalization and militarization of the society, festivals were washed out from practice and memory of the local communities were replaced with religious gatherings, training sessions and night vigils to instil a Jihadi spirit in the youth. Pashtun socio-cultural and political institutions and leadership is under continuous attack and voices of the people in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and FATA find little or no space in the mainstream Pakistani media. Hundreds of families are still displaced from their homes; women and children are suffering from acute psychological trauma. Introduction Pashtuns inhabit South Eastern Afghanistan and North Western Pakistan and make one of the largest tribal societies in the world. The Pashtun dominated region along the Pak-Afghan border is in the media limelight owing to terrorists’ activities and gross human rights violations. After the United States toppled Taliban regime in Afghanistan in 2001, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) became the prime destination for fleeing Taliban and Al-Qaeda fighters and got immense * Shaheen Buneri is a journalist with RFE/RL Mashaal Radio in Prague. Currently he is working on his book on music censorship in the Pashtun dominated areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan. 63 Tigah importance in the strategic debates around the world. -

The Nexus of Religious Extremism and Pakhtun Culture: Myths and Realities

TAKATOO Issue 4 Volume 7 July- December 2015 14 The Nexus of Religious Extremism and Pakhtun Culture: Myths and Realities Dr.Abdul Qadir Khan * Z Dr. Adil Zaman Kasi Y Syed Amir Shah Abstract : After the end of cold war, the ascendency of Taliban in Afghanistan, the rise of religious extremism in frontier regions of Pakistan and Pashtun nationalism has become one of the hotly debated issues. The Pashtun identity, its historical evolution and relationship with religion can be depicted from a statement of Khan Abdul Wali Khan which he gave during 1980s that whether he was a Pashtun first, a Pakistani or a muslim. His famous reply was that he had been a Pashtun for last three thousand years, a muslim for thirteen hundred years and a Pakistani for only twenty five years. This statement shows a complicated nature of Pashtun nationalism especially in wake of post 9/11 world, in which a rise of Taliban phenomenon has overshadowed many of its original foundations. Many scholars in the west and from within the country attribute the rise of talibanization in Pashtun society to the culture of pashtuns. To them, Pashtun culture has many aspects that help promote radical ideas. For examplethe overwhelming majority of Pashtun population adheres to deobandi school of thought unlike in Punjab which follows brelvi school of thought. Similarly, the rise of talibanization is also cited as an evidence for their claim that Pashtun culture is very conducive for promotion of radical ideas. Thus, these scholars draw close relationship between Pashtun nationalism and talibanization and make them appear as two faces of same coin. -

Far Middle East: an Annotated Bibliography of Materials at Elementary School Level for Afghanistan,' Iran, Pakistan

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 732 SO 008 034 AUTHOR James, Eloise Lucille TITLE Far Middle East: An Annotated Bibliography of Materials at Elementary School Level for Afghanistan,' Iran, Pakistan. PUB DATE Aug 74 NOTE 126p. EDRS PRICE NF -$0.76 HC-$6.97 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; Bibliographies; Cross Cultural Studies; *Cultural Awareness; Elementary Education; *Instructional Materials; Instructional Media; Interdisciplinary Approach; International Education; *Middle Eastern Studies; *Social Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Afghanistan; Iran; Pakistan ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography presents sources of data on the culture of the plateau-region of Western Asia - -an introduction to its culture, way of life, values, customs, laws, religious beliefs, technology, social institutions, language, and creative products. Section 1 contains bibliographic listings for adult instructional team members. A bibliography of bound print items comprises section 2, including general references, trade books, and textbooks. Section 3 is a bibliography of audiovisual items including kits, films, records, slides, maps, and realia. The fourth section lists serial items such as stamps, magazines, newspapers, and National Geographic Educational Services. A bibliography of less tangible sources, such as international reference sources, handouts, and human resources is included in section 5. A section on the future concludes the document, giving a summary of attitudes and gaps to be filled in Far Middle Xastern materials. (Author/JR) U.S -

The Effects of Militancy and Military Operations on Pashtun Culture and Religion in FATA

ISSN: 2664-8148 (Online) LASSIJ Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal Vol. 3, No. 1, (January-June) 2019, 73-82 Research Article www.lassij.org ___________________________________________________________________________ The Effects of Militancy and Military Operations on Pashtun Culture and Religion in FATA Surat Khan1*, Tayyab Wazir2 and Arif Khan3 1. Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences University of Peshawar, Pakistan. 2. Department of Defence & Strategic Studies, Quaid-e-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. 3. Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Buner, Pakistan. ………………………………………………………………………………………………… Abstract Two events in the last five decades proved to be disastrous for the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), now part of KP province: the USSR invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and ‘War on Terror' initiated by the US against militants in Afghanistan in 2001. After the incident of 9/11, FATA became the centre of global terrorism and emerged as the most dangerous place. Taliban’s rule was overthrown in Kabul, and they escaped and found refugees across the eastern border of Afghanistan with Pakistan. This paper aims at studying the emergence of Talibanization in FATA and its impacts on the local culture and religion. Furthermore, the research studies the effects of military operations on FATA’s cultural values and codes of life. Taliban, in FATA, while taking advantage of the local vulnerabilities and the state policy of appeasement, started expanding their roots and networks throughout the country. They conducted attacks on the civilians and security forces particularly when Pakistan joined the US ‘war on terror.’ Both the militancy and the military operations have left deep imprints thus affected the local culture, customs, values, and religious orientations in FATA. -

Download in PDF Format

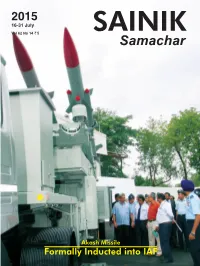

In This Issue Since 1909 COVERIndian STORY Air Force Formally Inducts The Akash Missile 4 (Initially published as FAUJI AKHBAR) Vol. 62 No 14 25 Ashadha - 9 Shravana, 1937 (Saka) 16-31 July 2015 The journal of India’s Armed Forces published every fortnight in thirteen languages including Hindi & English on behalf of Ministry of Defence. It is not necessarily an organ for the expression of the Government’s defence policy. The published items represent the views of respective writers and correspondents. Editor-in-Chief CNS Reviews the Passage from Karwar Hasibur Rahman 8 12 Editor Editor (Features) Passing out Parade to Salalah Dr Abrar Rahmani Ehsan Khusro Coordination Business Manager Sekhar Babu Madduri Dharam Pal Goswami Our Correspondents DELHI: Dhananjay Mohanty; Capt DK Sharma; Manoj Tuli; Nampibou Marinmai; Wg Cdr Rochelle D’Silva; Col Rohan Anand; Wg Cdr SS Birdi, Ved Pal; ALLAHABAD: Gp Capt BB Pande; BENGALURU: Dr MS Patil; CHANDIGARH: Parvesh Sharma; CHENNAI: T Shanmugam; GANDHINAGAR: Wg Cdr Abhishek Matiman; GUWAHATI: Lt Col Suneet Newton; IMPHAL: Lt Col Ajay Kumar Sharma; JALANDHAR: Naresh Vijay Vig; JAMMU: Lt Col Manish Mehta; JODHPUR: Lt Col Manish Ojha; KOCHI: Cdr Sridhar E Warrier ; KOHIMA: Lt Col E Musavi; KOLKATA: 6 Defence Minister Inaugurates… Gp Capt TK Singha; LUCKNOW: Ms Gargi Malik Sinha; MUMBAI: Cdr Rahul 10 IAF in Rescue and Relief… Defence Pension Sinha; Narendra Vispute; NAGPUR: Wg Cdr Samir S Gangakhedkar; PALAM: Gp Adalat Held 16 Capt SK Mehta; PUNE: Mahesh Iyengar; SECUNDERABAD: MA Khan Shakeel; 11 To Build and Promote Military… SHILLONG: Gp Capt Amit Mahajan; SRINAGAR: Col NN Joshi; TEZPUR: Lt Col 14 Release of IMA Journal and… Sombith Ghosh; THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Suresh Shreedharan; UDHAMPUR: 15 Naushera Ka Sher and his… Col SD Goswami; VISAKHAPATNAM: Cdr CG Raju. -

2016 Contested Spaces in Cities As Politicised As Jerusalem?

PROFILE HANNA BAUMANN DIVIDED CITY Hanna Baumann Can culture act as a bridge to connect groups who are in conflict? How do divided cities operate on a day to day basis? AndYEARBOOK how do people negotiate2016 contested spaces in cities as politicised as Jerusalem? Hanna Baumann [2012] has been fascinated by the subject of divided cities since she was young. Her PhD in Architecture will build on her undergraduate and Master’s research, which focused on the Israeli/Palestinian conflict as well as on work she has been doing in for the United Nations on minority cultural rights in conflict affected areas. Hanna showed an early interest in the intersection between culture and conflict. Growing up in what was then East Berlin, she was five when the Berlin Wall fell. “In some ways, it was a formative experience,” she says, “and was part of my interest in divided cities. Even after the Wall came down I could see the long-term effects on family and friends.” “I could feel the tension in the After graduating from Barnard, Hanna returned to the Middle streets of the old city, where East to work with Iraqi refugees in Jordan through the UNHCR. She then joined the humanitarian organisation ACTED in Jews and Muslims uneasily shared Jerusalem, working on agriculture, shelter and food security spaces holy to both groups,” projects. She says it was striking to see how in the Israel- Palestine context even seemingly innocuous activities like As an undergraduate at Barnard College, Columbia University, agriculture were deeply intertwined with questions of belonging she completed a dual major in Art History and the History of the and ownership.