Comparing the Methods of Andronikos I and Alexios I Komnenos of Constructing Imperial Power*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Περίληψη : Manuel Laskaris Was a Member of the Laskaris Family and One of the Six Brothers of Theodore I Laskaris (1204-1222)

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Γιαρένης Ηλίας Μετάφραση : Βελέντζας Γεώργιος Για παραπομπή : Γιαρένης Ηλίας , "Manuel Laskaris ", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=7801> Περίληψη : Manuel Laskaris was a member of the Laskaris family and one of the six brothers of Theodore I Laskaris (1204-1222). In the years of John III Vatatzes (1222-1254), he was in disgrace, while when Theodore II Laskaris assumed the throne (1254-1958), he was recalled along with the rest of his relatives. He became an important trusty counselor of the emperor and was honoured by him with the notable title of protosebastos. He was not a successful fighter in the battlefield, though. After Theodore II died in 1258, he did not support the election of Michael Palaiologos as the regent of John IV Laskaris and, as a result, was exiled in Prousa. Άλλα Ονόματα Manuel Komnenos Laskaris, Manuel Tzamanturos, Maximos Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης late 12th / early 13th century Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου third quarter of the 13th century Κύρια Ιδιότητα protosebastos 1. Βiography Manuel Laskaris was the youngest brother of the emperor of Nicaea Theodore I Komnenos Laskaris, and the last of all six Laskaris brothers. The Laskaris brothers from the eldest to the younger were: Isaac, Alexios, Theodore (I Komnenos Laskaris, emperor in the exile of Nicaea), Constantine (XI Laskaris, uncrowned Byzantine emperor), Michael and Manuel.1 The activity of Michael Laskaris is also mentioned by George Akropolites, Theodore Skoutariotes and George Pachymeres, who calls him ‘Tzamanturos’( Tζαμάντουρος).2 There is information about his life and work until Michael VIII assumed the throne; Michael Laskaris must have died in exile in Prousa. -

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi A struggle for supremacy 867 - 1071 J.J.P. Vrijaldenhoven S0921084 Van Speijkstraat 76-II 2518 GE ’s Gravenhage Tel.: 0628204223 E-mail: [email protected] Master Thesis Europe 1000 - 1800 Prof. Dr. P. Stephenson and Prof. Dr. P.C.M. Hoppenbrouwers History University of Leiden 30-07-2014 CONTENTS GLOSSARY 2 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER 1 THE FIRST STRUGGLE OF THE DYNATOI AND THE STATE 867 – 959 16 STATE 18 Novel (A) of Leo VI 894 – 912 18 Novels (B and C) of Romanos I Lekapenos 922/928 and 934 19 Novels (D, E and G) of Constantine VII Porphyrogenetos 947 - 959 22 CHURCH 24 ARISTOCRACY 27 CONCLUSION 30 CHAPTER 2 LAND OWNERSHIP IN THE PERIOD OF THE WARRIOR EMPERORS 959 - 1025 32 STATE 34 Novel (F) of Romanos II 959 – 963. 34 Novels (H, J, K, L and M) of Nikephoros II Phokas 963 – 969. 34 Novels (N and O) of Basil II 988 – 996 37 CHURCH 42 ARISTOCRACY 45 CONCLUSION 49 CHAPTER 3 THE CHANGING STATE AND THE DYNATOI 1025 – 1071 51 STATE 53 CHURCH 60 ARISTOCRACY 64 Land register of Thebes 65 CONCLUSION 68 CONCLUSION 70 APPENDIX I BYZANTINE EMPERORS 867 - 1081 76 APPENDIX II MAPS 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 82 1 Glossary Aerikon A judicial fine later changed into a cash payment. Allelengyon Collective responsibility of a tax unit to pay each other’s taxes. Anagraphis / Anagrapheus Fiscal official, or imperial tax assessor, who held a role similar as the epoptes. Their major function was the revision of the tax cadastre. It is implied that they measured land and on imperial order could confiscate lands. -

The Case of Michael Glykas' Letter Collection and Biblos Chronike In

DOI 10.1515/bz-2020-0036 BZ 2020; 113(3): 837–852 Eirini-Sophia Kiapidou Writing lettersand chronography in parallel: the case of Michael Glykas’ letter collection and Biblos Chronike in the 12th century Abstract: This paper focuses on the 12th-century Byzantine scholarMichael Gly- kas and the two main pillars of his multifarious literaryproduction, Biblos Chronike and Letters, thoroughly exploring for the first time the nature of their interconnection. In additiontothe primary goal, i.e. clarifying as far as possible the conditions in which these twoworks were written, taking into account their intertextuality,itextends the discussion to the mixture of features in texts of dif- ferent literarygenre, written in parallel, by the same author,basedonthe same material. By presentingthe evidence drawnfrom the case of Michael Glykas, the paper attemptstostress the need to abandon the strictlyapplied taxonomical logic in approaching Byzantine Literature, as it ultimatelyprevents us from con- stitute the full mark of each author in the history of Byzantine culture. Adresse: Dr.Eirini-Sophia Kiapidou, UniversityofPatras, Department of Philology,Univesity Campus,26504Rio Achaia, Greece;[email protected] Accordingtothe traditionalmethod of approaching Byzantine Literature,asap- plied – under the influenceofclassical philology – in the fundamental works of Karl Krumbacher,¹ Herbert Hunger² and Hans-Georg Beck³ and indeedrepro- Ι wish to thankProfessor StratisPapaioannou as wellasthe two anonymous readersfor making valuable suggestions on earlier versions of thispaper.All remaining mistakes, of course,are mine. K. Krumbacher,Geschichteder byzantinischen Litteratur vonJustinian bis zum Ende des os- trömischen Reiches (–). München . H. Hunger, Die hochsprachliche profane Literatur der Byzantiner. Handbuch der Altertumwis- senschaft ..,I–II. München . H.-G. -

The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) and the Western Way of War the Komnenian Armies

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 11 (2008-2009) Viewpoints 1 The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) and the Western Way of War The Komnenian Armies Byzantium. The word invokes to the modern imagination images of icons, palaces and peaceful Christianity rather than the militarism associated with its European counterparts during the age of the Byzantine Empire. Despite modern interpretations of the Empire, it was not without military dynamism throughout its 800-year hold on the East. During the “Second Golden Age” of Byzantium, this dominion experienced a level of strength and discipline in its army that was rarely countered before or after. This was largely due to the interest of the Komnenian emperors in creating a military culture and integrating foreign ideas into the Eastern Roman Empire. The Byzantine Empire faced unique challenges not only because of the era in which they were a major world power but also for the geography of Byzantium. Like the Rome of earlier eras, the territory encompassed by Byzantium was broad in scope and encompassed a variety of peoples under one banner. There were two basic areas held by the empire – the Haemus and Anatolia, with outposts in Crete, the Crimea and southern Italy and Sicily (Willmott 4). By the time of the Komnenos dynasty, most of Anatolia had been lost in the battle of Manzikert. Manuel I would attempt to remedy that loss, considered significant to the control of the empire. Of this territory, the majority was arid or mountainous, creating difficulties for what was primarily an agricultural economy. This reliance on land-based products helped to bolster the reluctance for war in the eastern Roman Empire. -

Niketas Choniates Versus Manuel I Komnenos: Disputes Concernig Islam in the Context of the Byzantine Tradition

Списание ЕПОХИ Издание на Историческия факултет на ВТУ „Св. св. Кирил и Методий” Том / Volume XXIV (2016), Journal EPOHI [EPOCHS] Книжка / Issue 2 Edition of the Department of History of St. Cyril and St. Methodius University of Veliko Turnovo NIKETAS CHONIATES VERSUS MANUEL I KOMNENOS: DISPUTES CONCERNIG ISLAM IN THE CONTEXT OF THE BYZANTINE TRADITION Dimitar Y. DIMITROV НИКИТА ХОНИАТ СРЕЩУ МАНУИЛ I КОМНИН: ПОЛЕМИКА, СВЪРЗАНА С ИСЛЯМА, В КОНТЕКСТА НА ВИЗАНТИЙСКАТА ТРАДИЦИЯ Димитър Й. ДИМИТРОВ Abstract: Byzantine society had very complex relations with the Islamic Eastern neighbors. Islam, to be sure, started and continued to be menace for Byzantium for the all long eighth centuries they used to coexist. However, Byzantine society needed a certain period of time to accept Islam as another religion, standing against Christianity in the East. After the first Byzantine revenge acts against Judaism a long tradition was formed with two main streams. The first of them envisaged Islam as a demoniac pseudo-religion (or anti-religion), the second being milder and ready to accept the Islamic neighbors not as a whole, but rather as different states, culturally not so different from Byzantium, with diplomacy playing role for keeping balance in the East. Thus, the Byzantine Realpolitik appeared as a phenomenon, what provoked crusaders to accuse Byzantium as being traitor to the Christian cause in the East. In that context should we pose the interesting incident at the end of Manuel I Komnenos’ reign (1143 – 1180). Both Church and society were provoked by the decision of the Emperor to lift up the anathemas against Allah from the trivial ritual of denouncing Islam. -

Constantinople 1 L Shaped H

The Shroud of Turin in Constantinople? Paper I An analysis of the L Shaped markings on the Shroud of Turin and an examination of the Holy Mandylion and Holy Shroud in the Madrid Skylitzes © Pam Moon Introduction This paper begins by looking at the pattern of marks on the Shroud of Turin which look like an L shape. The paper examines [1] the folding patterns, [2] the probable cause of the burn marks, and argues, with Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito that it is accidental damage from incense. [3] It compares the marks with the Hungarian Pray manuscript. [4] In the second part, the paper looks at the historical text The Synopsis of the Histories attributed to Ioannes (John) Skylitzes. The illustrated history is known as the Madrid Skylitzes. It is the only surviving illustrated manuscript for Byzantine history for the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries. The paper looks at images from the Madrid Skylitzes which relate to the Holy Mandylion, also known as the Image of Edessa. The Mandylion was the most precious artefact in the Byzantine empire and is repeatedly described as an image ‘not-made-by-hands.’ [5] The paper identifies a miniature in the Madrid Skylitzes (fol.26v; see below) which apparently shows the procession of a beheaded emperor Leon V in AD 820 and suggests that there could be a scribal error. The picture seems to show the Varangian Guard who arrived in Constantinople after AD 988, 168 years later. The picture may instead depict the procession of AD 1036, where the Holy Mandylion (and in some translations Holy Shroud) were carried though the streets of Constantinople. -

Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

A “Truly Unmonastic Way of Life”: Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hannah Elizabeth Ewing Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Timothy Gregory, Advisor Professor Anthony Kaldellis Professor Alison I. Beach Copyright by Hannah Elizabeth Ewing 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines twelfth-century Byzantine writings on monasticism and holy men to illuminate monastic critiques during this period. Drawing upon close readings of texts from a range of twelfth-century voices, it processes both highly biased literary evidence and the limited documentary evidence from the period. In contextualizing the complaints about monks and reforms suggested for monasticism, as found in the writings of the intellectual and administrative elites of the empire, both secular and ecclesiastical, this study shows how monasticism did not fit so well in the world of twelfth-century Byzantium as it did with that of the preceding centuries. This was largely on account of developments in the role and operation of the church and the rise of alternative cultural models that were more critical of traditional ascetic sanctity. This project demonstrates the extent to which twelfth-century Byzantine society and culture had changed since the monastic heyday of the tenth century and contributes toward a deeper understanding of Byzantine monasticism in an under-researched period of the institution. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family, and most especially to my parents. iii Acknowledgments This dissertation is indebted to the assistance, advice, and support given by Anthony Kaldellis, Tim Gregory, and Alison Beach. -

6 X 10.Long.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85703-1 - Imperial Ideology and Political Thought in Byzantium, 1204-1330 Dimiter Angelov Index More information Index abiotikion 288–89, 297, 302–03 Aphthonios 18, 54–55, 56, 73, 92, 200 Agapetos theDeacon 154, 185–87, 194–95, 230 Apokaukos, John 187, 192, 357 Ahrweiler,He´le`ne 5–6, 10–11 Apros, battle of (10 July 1305) 292, 316 Akindynos, Gregory 297 Aquinas, Thomas 24 Akropolites, George 43, 49, 50, 57, 67, 69, 84, Argyropoulos, John 63 93, 99, 124, 136, 137–38, 167, 207–08, Aristides, Aelius 57, 58–59, 126 209, 246, 255, 257, 258, 345 aristocracy 9 Alanmercenaries 291, 303, 316 as constitutionalformofgovernment 200–01, Alexios I Komnenos, emperor 4, 62, 118, 119, 323 126, 167, 331 nature andpolitical clout of 4–5, 109–10 Alexios III Angelos, emperor 2, 119, 120, 125, 129, opposition against 5, 105–07, 179, 209–12, 412 234, 303 Andronikos I Komnenos, emperor 137, 282, 284 see also nobility (eugeneia), conceptof Andronikos II Palaiologos, emperor 7, 30, Aristotle 8, 9, 24, 69, 195, 227, 260, 345, 421 45–47, 56–57, 109, 118, 127, 130–32, 136, Nicomachean Ethics 23, 197, 220–22, 250 148, 169, 177, 262, 268, 278–79, 280, 282, Politics 23, 202–03, 251, 321 290–92, 299, 301, 302, 303, 311, 313, 314, Rhetoric 55 316, 318, 338–40, 342, 354, 369, 371, 395, Arsenios Autoreianos, patriarch of 397–401, 407, 412 Constantinople (in Nicaea during his portrait in court rhetoric 101–02, 103, 110–12, first term inoffice) 44, 296, 329, 366–69, 113–14, 136–40, 141–43, 152–53, 165, 170 374–75, 380–81, 382, 383, 393, 394–95 -

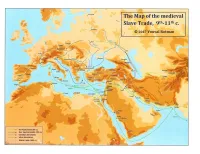

The Map Is Based on the Following Data Organized Chronologically and Geographically

The map is based on the following data organized chronologically and geographically Table 1: data concerning the slave trade in the medieval Mediterranean 8th-11th c. Western Europe Central Europe Italy-Adriatic Sea Syria-Palestine- Byzantium Balkans Caucasus-Black Iraq-Iran Egypt Sea-Russia 7th –8th c.: the 712: first Rhodian Sea Law kommerkiarioi, 729: Itil, first (mentions of attested in evidences 776: letter from trafficked slaves) Thessalonica 740: documents 762: Abbassids Pope Hadrian I to 728: last known (including of slaves) attesting Jews settle in Charlemagne sigillographical among the Baghdad regarding the mention of Khazars slave trade apothēkai 801: Irene lowers 8th c.: Abydikoi taxes (responsible of 812/814: the 809: Nicephorus I import taxes) of Franks leave the taxes slaves Thessalonica Adriatic Sea entering by the attested 822–852: al- 814–820: 824: Arab Dodecanese Ghazāl on the Byzantino- conquest of Crete Spain-Baltic Venetian edict routes against trade 833–844: Arab 841: the thema of 846: first 825: privileges with the Arabs raids in Sicily and 831–833: new Kherson version of granted by Louis 831: Arab Peloponnesus; kommerkiarioi mid-ninth Kitāb al- the Pious to a conquest of Byzantine raids century: Masālik wa’l- Jewish merchant Palermo in Syria 860: the Serbs pay -Life of George of mamālik, by of Sargossa 830–860: Arab their tribute to the Amastris (tax in Ibn 846: Agobard of raids in southern Bulgars in slaves Trebizond). Ḵhurradāḏhbih Lyons writes Italy 864: - Rus’ merchants : references to against the Christianization -

Some Thoughts on the Military Capabilities of Alexios I Komnenos: Battles of Dyrrachion (1081) and Dristra (1087)

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 2 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-2-10 Some Thoughts on the Military Capabilities of Alexios I Komnenos: Battles of Dyrrachion (1081) and Dristra (1087) Marek Meško (Masaryk University) ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES Abstract Alexios I Komnenos belongs to the most important emperors of the Byzantine history. Yet, in many respects, this period still remains an underdeveloped field of study. This paper attempts to review one of the aspects of his reign, namely his capabilities as a military commander since he owed much of his success in restoring the fortunes of Byzantium to his strong military back- ground. In order to succeed in the final evaluation, most of the relevant military events during Alexios Komnenos’ life and career in which he took personal part will be briefly reviewed and taken into consideration. Particular cases where Alexios Komnenos was allegedly responsible for a serious military defeat will be discussed in more detail (e.g. battle of Dyrrachion in 1081 and battle of Dristra in 1087) in order to assess whether it was solely Alexios Komnenos’ re- sponsibility, or whether the causes of defeat were not result of his faulty decision-making as a military commander. Keywords Byzantine Empire; Alexios Komnenos; military; battles; medieval warfare 143 Marek Meško Some Thoughts on the Military Capabilities of Alexios I Komnenos: Battles of Dyrrachion (1081) … Introduction The Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) is a very well-known charac- ter of the Byzantine history. At the same time, he is famous as the emperor who sat on the throne of Byzantium when the crusaders of the first crusade headed east to liber- ate Jerusalem. -

Alexius Komnenos and the West and So It Begins...76Th Emperor

3/14/2012 Alexius Komnenos and the West HIST 302 Spring 2012 And so it begins...76th Emperor 4 April 1081 ascended to the throne • 24 years old • short and stocky; deep chested; broad shoulders • seen action against the Seljuks – never lost a battle • uncle was Isaac Komnenus • married to the 15 year old Irene Ducas – assured support of aristocracy and clergy • his ascension was a little messy... Komneni Dynasty (1081-1185) 1057-9 Isaac I 1071 Battle of Manzikert 1081-1118 Alexios I 1118-43 John II 1143-80 Manuel I 1180-2 Alexios II 1182-5 Andronikos I 1 3/14/2012 War with the Normans • Robert Guiscard (the crafty) 1071 Bari fell 1081 giant fleet sailed towards Durazzo – road to Constantinople • Alexius shows up with his army – Varangians (mostly A-S refugees pissed off at Normans) wanting revenge • Alexius wounded in battle – retires to Thessalonica 2 3/14/2012 Gregory VII, besieged in Castel Sant'Angelo Tomb of Guiscard at Venosa Robert Guiscard dies of Typhoid in 1085 Normans Conquer S. Italy • Normans conquer Sicily and S. Italy • Cousin of Roger Guiscard organizes a new Kingdom Roger II, the Norman (ruled from 1130-1154) 3 3/14/2012 Palazzo Reale, Naples Roger II Frederick II Alfonso Charles V Charles III Charles of Anjou Gioacchino Murat Victor Emanuel II Norman Hohenstaufen Aragon Hapsburg Bourbon (1266-1285) (1808-1815) (1861-1878) (1130-1154) (1211-1250) (1442-1458) (1520-1558) (1734-1759) Alexius Receives Papal Mission Pope Gregory VII – excommunicated Alexius for helping HRE Pope Urban II • trying to restore unity b/t E &W