A Natural Pulse Man-Made Pulses Beats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Nozze Di Figaro' Author(S): John Platoff Source: Music & Letters, Vol

Tonal Organization in 'Buffo' Finales and the Act II Finale of 'Le nozze di Figaro' Author(s): John Platoff Source: Music & Letters, Vol. 72, No. 3 (Aug., 1991), pp. 387-403 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/736215 Accessed: 26-02-2019 18:45 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Music & Letters This content downloaded from 132.174.255.206 on Tue, 26 Feb 2019 18:45:02 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms TONAL ORGANIZATION IN 'BUFFO' FINALES AND THE ACT II FINALE OF 'LE NOZZE DI FIGARO' BY JOHN PLATOFF THE TONAL PLAN of the finale to Act II of Mozart and Da Ponte's Le nozze di Fzgaro is an admirably clear structure, and one that has drawn nearly as much ap- proving comment from analysts as the opera itself has received from audiences.' The reasons for this favourable view of the finale's tonal scheme are not hard to find: its eight sections or movements move from the tonic of E flat to the dominant and then by a descending third to G, from which point the return to the tonic occurs through a regular series of falling fifths (see Table I). -

S Y N C O P a T I

SYNCOPATION ENGLISH MUSIC 1530 - 1630 'gentle daintie sweet accentings1 and 'unreasonable odd Cratchets' David McGuinness Ph.D. University of Glasgow Faculty of Arts April 1994 © David McGuinness 1994 ProQuest Number: 11007892 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007892 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 10/ 0 1 0 C * p I GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ERRATA page/line 9/8 'prescriptive' for 'proscriptive' 29/29 'in mind' inserted after 'his own part' 38/17 'the first singing primer': Bathe's work was preceded by the short primers attached to some metrical psalters. 46/1 superfluous 'the' deleted 47/3,5 'he' inserted before 'had'; 'a' inserted before 'crotchet' 62/15-6 correction of number in translation of Calvisius 63/32-64/2 correction of sense of 'potestatis' and case of 'tactus' in translation of Calvisius 69/2 'signify' sp. 71/2 'hierarchy' sp. 71/41 'thesis' for 'arsis' as translation of 'depressio' 75/13ff. Calvisius' misprint noted: explanation of his alterations to original text clarified 77/18 superfluous 'themselves' deleted 80/15 'thesis' and 'arsis' reversed 81/11 'necessary' sp. -

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms CHRIS BALDICK OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD PAPERBACK REFERENCE The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms Chris Baldick is Professor of English at Goldsmiths' College, University of London. He edited The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales (1992), and is the author of In Frankenstein's Shadow (1987), Criticism and Literary Theory 1890 to the Present (1996), and other works of literary history. He has edited, with Rob Morrison, Tales of Terror from Blackwood's Magazine, and The Vampyre and Other Tales of the Macabre, and has written an introduction to Charles Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer (all available in the Oxford World's Classics series). The most authoritative and up-to-date reference books for both students and the general reader. Abbreviations Literary Terms Oxford ABC of Music Local and Family History Paperback Accounting London Place Names* Archaeology* Mathematics Reference Architecture Medical Art and Artists Medicines Art Terms* Modern Design* Astronomy Modern Quotations Better Wordpower Modern Slang Bible Music Biology Nursing Buddhism* Opera Business Paperback Encyclopedia Card Games Philosophy Chemistry Physics Christian Church Plant-Lore Classical Literature Plant Sciences Classical Mythology* Political Biography Colour Medical Political Quotations Computing Politics Dance* Popes Dates Proverbs Earth Sciences Psychology* Ecology Quotations Economics Sailing Terms Engineering* Saints English Etymology Science English Folklore* Scientists English Grammar Shakespeare English -

Course Outline

MUSICIANSHIP - Course Outline General information about the approach Audiation - the ability to think in sound - is at the core of musicianship training. Musical elements and concepts are sequentially introduced, from the simple to the complex, and are practiced in ways that actively develop understandings in pitch, tonality, rhythm and harmony. These understandings are reinforced through engagement in a variety of modes of learning: aural (critical listening, the linking of sound to syllable using tonic solfa, absolute pitch names and rhythm duration syllables), kinaesthetic (use of the Curwen hand sign system, conducting patterns and other physical indications for beat, rhythm, phrase), and visual (linking sound to a variety of notational systems). Thorough musicianship practise involves using musical elements and concepts in known contexts (such as in performing, part work and memorisation), and unknown contexts (such as in sight reading, dictation, improvisation and composition). True musicianship is achieved not only when known elements can be successfully reproduced in these many contexts, but when they are applied with sensitivity to genre and culture, and then imbued with appropriate personal expression. Artistic training must equally involve active engagement and reflection. This is the key to developing the musical imagination in both intellectual and emotional realms. Overview: Musicianship involves the study of sight singing, score reading, aural perception, musical dictation and analysis using the tools of the Kodály philosophy (tonic solfa, rhythm duration syllables and hand signs). This class will study core repertoire as decided by the course lecturer. All participants will complete a 1.5hr class of Musicianship each day. These classes provide intensive skill development in aural musicianship as well as theoretical components of music. -

Rhythm and Metre Definition of Key Terms

Area of Study One Rhythm and Metre Definition of Key Terms Key Word Definition Pulse The beat in a piece of music Metre The number of beats in a bar Tempo The speed of the music – measured in BPM and also uses metronome markings Simple Time Time signatures where the beat is divided into two: typically, a crotchet beat divided into two quavers Compound Time Time signatures based on a dotted crotchet beat, divided into three quavers, for example 6/8 Regular Time Music which keeps to a single time signature Irregular Time Music where the time signature changes (usually a lot), or where the accents frequently shift Free Time Where the rhythm of the music is not set by regular bar lines but determined by the performer Hemiola Where two bars of 3/4 are played as three bars of 2/4 or one bar of 3/2 Cross rhythm When two different rhythms of usually different metres are played together at the same time Dotted rhythm The effect produced when two conflicting rhythms are heard together Triplet Three notes being played in the time of two Syncopation When the notes are played off the beat Rubato Literally ‘robbed time’, where rhythms are played freely for expressive effect Polyrhythm When two or more rhythms are played at the same time. (Often with different pulses) Drum fill Usually heard at the end of a phrase, this is where the drummer plays a free rhythmic pattern Italian Tempo Markings Italian Term Meaning Largo Slowly and broadly Adagio ‘At ease’ (play slowly) Andante At a walking pace Moderato At moderate speed Allegro Fast Vivace Lively Presto Very quick Accelerando Gradually speeding up Rallentando Gradually slowing down Ritenuto Immediately slower Allargando Getting slower and broadening Time Signatures ! " Time signatures contain two numbers ! " The top number indicates the number of beats in each bar ! " The bottom number indications the length of each beat. -

Note Value Recognition for Piano Transcription Using Markov Random Fields Eita Nakamura, Member, IEEE, Kazuyoshi Yoshii, Member, IEEE, Simon Dixon

JOURNAL OF LATEX CLASS FILES, VOL. XX, NO. YY, ZZZZ 1 Note Value Recognition for Piano Transcription Using Markov Random Fields Eita Nakamura, Member, IEEE, Kazuyoshi Yoshii, Member, IEEE, Simon Dixon Abstract—This paper presents a statistical method for use Performed MIDI signal 15 (sec) 16 1717 1818 199 20 2121 2222 23 in music transcription that can estimate score times of note # # # # b # # onsets and offsets from polyphonic MIDI performance signals. & # # # Because performed note durations can deviate largely from score- ? Pedal indicated values, previous methods had the problem of not being able to accurately estimate offset score times (or note values) Hidden Markov model (HMM) etc. and thus could only output incomplete musical scores. Based on Incomplete musical score by conventional methods observations that the pitch context and onset score times are nœ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ œ œ œ influential on the configuration of note values, we construct a # 6 œ œ œ œ nœ & # 8 œ œ œ œ œ œ bœ nœ #œ œ context-tree model that provides prior distributions of note values œ œ #œ nœ œ œ œ œ œ nœ œ œ œ œ ? # 6 œ n œ œ œ œ œ œ œ # 8 œ using these features and combine it with a performance model in (Rhythms are scaled by 2) the framework of Markov random fields. Evaluation results show Markov random field (MRF) model that our method reduces the average error rate by around 40 percent compared to existing/simple methods. We also confirmed Complete musical score by the proposed method that, in our model, the score model plays a more important role # œ nœ œ œ œ œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ ˙. -

Music Early Years Year Group Learning Objective Knowledge

Kentmere Academy and Nursery- Knowledge and Skills- Music Early Years Year Learning Objective Knowledge Skills Group Early To join in singing favourite songs. I know some popular nursery rhymes. I can identify my favourite songs. Years To create sounds by banging, shaking, tapping or I know that sounds can be created in many ways. I can join in with my favourite songs. blowing. I know that there are many different musical I can create sounds by banging, shaking, tapping instruments. To shows an interest in the way musical or blowing. I know that music has a beat. instruments sound. I can name some musical instruments. I know that a series of beats is called a rhythm. I am interested in the different sounds you can To sing a few familiar songs. I know that sounds can be changed. make with musical instruments. To beginning to move rhythmically. I know a variety of different songs. To imitate movement in response to music. I can sing some familiar songs. To taps out simple repeated rhythms. I can move to the beat of a piece of music. To explore and learn how sounds can be changed. I can repeat a rhythm. To begin to build a repertoire of songs and I can clap out a repeated rhythm. dances. I can explore sound and learn how to change it. To explore the different sounds of instruments. I can explore how instruments sound different to each other. I can sing a variety of songs. Cycle A- Year 1/2 Year Group Topic Week Learning Objective Knowledge Skills Year 1/2 Dinosaur Autumn 1 To learn and perform a song. -

(91420) 2013 Assessment Schedule

NCEA Level 3 Making Music (91420) 2013 — page 1 of 6 Assessment Schedule – 2013 Making Music: Integrate aural skills into written representation (91420) Evidence Statement Question Achievement Achievement with Merit Achievement with Excellence ONE “Shenandoah” (a) (i) Identifies the Italian words describing the instrumentation, AND gives the English meaning: Style: a capella • (the choir is) unaccompanied. (ii) Identifies AND explains the texture: Texture: homophonic • the melody in the soprano / upper part is accompanied by chords in the other parts. (iii) Identifies an appropriate Italian term for a tempo of 40–44 bpm. AND gives the English meaning, eg: • Largo – slow, broadly, dignified • Lento – slow • Adagio – slow • Andante – at a walking pace. (b) (i) Identifies the tonality AND gives ONE piece of evidence in support, eg: Tonality: major • the first chord is major • the third note of the scale is raised in the melody (eg the note on “’Tis seven long years since last…”) • the last chord is major. (ii) Identifies the articulation used AND gives the English meaning: • Legato – smoothly. (c) (i) Identifies the compositional Identifies the compositional device used in the last two bars: device used in the last two bars Device: imitation AND explains its use, eg: • the tenors and basses echo the melody sung on (“the wide Missouri”) by the sopranos and altos. (ii) Explains how the rhythm is varied in the last two bars, eg: • for the women, the notes of “wide Mis-” are the same length, but the men hold “wide” for longer (1½ beats). NCEA Level 3 Making Music (91420) 2013 — page 2 of 6 Question One (cont’d) Question Achievement Achievement with Merit Achievement with Excellence (d) Identifies the device used AND explains its use, eg: Device: augmentation • the same motif (“O Shenando’”) is repeated in notes of longer duration. -

Universiv Micrwilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1 The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. I f copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

An Introduction to Hardy's Poetry

1 An Introduction to Hardy’s Poetry Please note: this is a scanned and lightly edited version of the original. The pagination has changed from that in the book. Turning to poetry Hardy’s career as a poet is unique. After writing poetry in the 1860s, in the way that any young man with literary ambitions might, he established himself as a major Victorian novelist. When his novel-writing came to an end in 1895, he began a second career as a poet. The bulk of his poetry was thus produced between his fifty-fifth birthday and his death at the age of 87 (the exceptions are a number of poems first drafted in the 1860s: around sixty poems can be dated before 1890, including seven in this selection, though a number of other undated poems undoubtedly use early material). Though the late careers of poets like Victor Hugo and Wallace Stevens provide a comparison, few poets have written so well in late life. One set of questions presented by Hardy’s poetic career is thus: To what extent is he a ‘Victorian’ poet? What was the impact of a career that was undertaken after an established career as a novelist? How did he sustain his writing? What were Hardy’s own explanations of his continued productivity? The reasons for Hardy’s abandonment of the novel are complex. The motive he often gave was the hostile receptions of Tess of the D’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure. Public controversy was matched by private hostility as he became estranged from his increasingly evangelical wife, Emma, who felt betrayed by the latter novel’s bitter reflections on marriage and religion. -

Suggested Teaching Strategy

Rhythm, Metre, and Tempo: Key Terminology Starter Packs, Intermediate UK- Grade 3-4 ABRSM Theory and Year 10-11 GCSE; USA – Grades 9-10 Suggested Teaching Strategy These ‘starter’ packs are great for teaching key vocabulary for High School/ Secondary School Music, regardless of the syllabus that you use. Not only do they provide consistency to the start of your lessons, they ensure you are always able to tick that literacy and numeracy box (puzzles = maths!) for every lesson, without any further thought. There are 4 stages. Stage 1: Pre-teaching the key words. This is the Word Search activities (7 in this pack). There is nothing better to focus students’ minds on key words than trying to find the words in a word search. These should be done as a starter to the lesson. Stage 2: Pre-teaching the definitions. This is the Flash Card activities (7 in this pack). This should be the homework for the same lesson they complete the word search in. Through independent learning, students must write the key words and definitions in a grid. This grid can easily be transformed into flash cards for revision at a later date, by cutting, folding, and sticking. Stage 3: Teaching the terms. This is the Mix and Match activities in the answer booklets (7 in the pack). Guillotine and laminate the master answer sheets for the terms and full definitions. At the start of the lesson after the independent learning homework, have the students match the terms and definitions in groups. They can then check their own definitions against the master ones. -

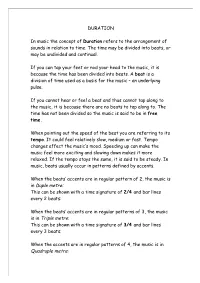

DURATION in Music the Concept of Duration Refers to the Arrangement

DURATION In music the concept of Duration refers to the arrangement of sounds in relation to time. The time may be divided into beats, or may be undivided and continual. If you can tap your feet or nod your head to the music, it is because the time has been divided into beats. A beat is a division of time used as a basis for the music – an underlying pulse. If you cannot hear or feel a beat and thus cannot tap along to the music, it is because there are no beats to tap along to. The time has not been divided so the music is said to be in free time. When pointing out the speed of the beat you are referring to its tempo. It could feel relatively slow, medium or fast. Tempo changes affect the music’s mood. Speeding up can make the music feel more exciting and slowing down makes it more relaxed. If the tempo stays the same, it is said to be steady. In music, beats usually occur in patterns defined by accents. When the beats’ accents are in regular pattern of 2, the music is in Duple metre: This can be shown with a time signature of 2/4 and bar lines every 2 beats: When the beats’ accents are in regular patterns of 3, the music is in Triple metre: This can be shown with a time signature of 3/4 and bar lines every 3 beats: When the accents are in regular patterns of 4, the music is in Quadruple metre: This can be shown with a time signature of 4/4 and bar lines every 4 beats: Metre is therefore the pattern of the beats’ accents.