Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio 10 Gold - Top 4000

Radio 10 Gold - Top 4000 http://www.radio10gold.nl/top4000.html positie titel / artiest jaar TIME BANDITS 4000 1983 listen to the man with the golden voice MICHEL SARDOU 3999 1975 une fille aux yeux clairs NICK STRAKER BAND 3998 1999 a walk in the park CHUBBY CHECKER 3997 1965 lovely lovely NEW YORK CITY 3996 1973 i'm doing fine now BENNY NEYMAN 3995 1980 ik weet niet hoe LA BOUCHE 3994 1995 be my lover 10 CC 3993 1974 silly love BLOOD SWEAT AND TEARS 3992 1969 spinning wheel GLORIA ESTEFAN 3991 1989 here we are K-CI & JOJO 3990 1999 tell me it's real THREE DEGREES 3989 1979 the runner RICCARDO COCCIANTE 3988 1984 sincerita BRITNEY SPEARS 3987 1999 sometimes KRISTINE W 3986 1994 feel what you want BILLY STEWART 3985 1966 summertime MARSHALL AND HAIN 3984 1978 dancing in the city CLUBHOUSE 3983 1983 do it again LITTLE RICHARD 3982 1957 the girl can't help it DUSTY SPRINGFIELD 3981 1989 nothing has been proved JENNIFER LOPEZ 3980 2000 let's get loud KIM WILDE 3979 1988 never trust a stranger MICHAEL JACKSON 3978 1979 ease on down the road SPLIT ENZ 3977 1981 i hope i never ISLEY BROTHERS 3976 1969 behind a painted smile BIG COUNTRY 3975 1986 look away NELLY FURTADO 3974 2007 all good things. BELLAMY BROTHERS 3973 1976 let your love flow LIVING IN A BOX 3972 1989 room in your heart VESTA WILLIAMS 3971 1987 once bitten twice shy BARRY AND EILEEN 3970 1975 if you go OHIO PLAYERS 3969 1975 fire. -

Vangelis Veröffentlicht Umfangreiches 13-Cd Deluxe Boxset

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 01805 - 060347 90476 [email protected] VANGELIS VERÖFFENTLICHT UMFANGREICHES 13-CD DELUXE BOXSET Der Musikvisionär Vangelis kündigt die für 3. Februar geplante Veröffentlichung eines neuen Boxsets mit 13 CDs an. “Delectus” enthält eine Auswahl seiner frühen Alben. In der gigantischen Collection befinden sich alle bei Vertigo und Polydor erschienen Alben – hier zum ersten Mal unter den aufmerksamen Augen des legendären Komponisten neu gemastert. Die CDs befinden sich in zwei gestanzten, aufklappbaren Haltern in einem quadratischen, stabilen Slipcase mit 242mm Seitenlänge. Diese wiederum werden zusammen mit einem 64-seitigen Buch über diesen speziellen Zeitabschnitt in der produktiven Karriere des legendären Künstlers in einer aufwendigen Box mit einem Essay und einer Reihe seltener Fotos aufbewahrt. “Ich freue mich immer, meine Alben zu remastern und zwar aus zwei Gründen”, erklärt Vangelis. “Erstens gibt es mir eine Gelegenheit, den Sound den heutigen Standards anzupassen und zweitens kann ich mich noch einmal mit meinen Erfahrungen und Erinnerungen aus der jeweiligen Zeit auseinandersetzen.” “Delectus” beinhaltet die bahnbrechenden Werke “Earth”, “L’Apocalypse Des Animaux”, “China”, “See You Later”, “Antarctica”, “Mask”, “Opera Sauvage”,“Chariots of Fire”, “Soil Festivities” und “Invisible Connections”, sowie die in Kollaboration mit Jon Anderson als ‘Jon & Vangelis’ entstandenen Alben “Short Stories”, “The Friends of Mister Cairo” & “Private Collection”. Die remasterten Originalalben wurden durch seltene B-Seiten und vier bisher unveröffentlichte Tracks ergänzt. Vangelis gilt als ein Vorreiter in der Entwicklung der elektronischen Musik. In seiner beeindruckenden Musikkarriere hat er zahlreiche Alben komponiert und aufgenommen und dabei die unterschiedlichsten Musikstile abgedeckt. Am populärsten sind seine Filmsoundtracks, u. -

Proggnosis - CD/DVD/Album Release Information Page

ProGGnosis - CD/DVD/Album Release Information Page http://www.silverdb.com/MUSIC_DBCDInfo.asp?txtCDID=22528 SUPPORT OUR SPONSORS - CLICK BANNER TO VISIT THE SPONSOR'S SITE PROGGNOSIS RECORDING INFO PAGE Our 7th Anniversary Online - 2006 Ads by Google Folk Music Recording Band Recording Drum Recording Best Recording HD3 Recording Quick Comments & feedback to: Links Main Options Stats & About Writings Genre Guides Other Items SEARCH PROGGNOSIS: Artist/Band Name 6 "Anderson, Jon" "Live in Shef Search Search Live in Sheffield 1980 [Live] by: Anderson, Jon Year: 2007 42 Page View(s) PAGE JUMPS: RECORDING INFORMATION * REVIEWS * TRACKS, CREDITS & DISCOGRAPHY Learn Audio RECORDING INFORMATION Recording Voiceprint / Opio Media music production, mixing, Pro Tools & live sound from industry leaders. COMMENTS & REVIEWS www.cras.org Marc Published on: 15 Oct 2007 Audio School - In 1980 Jon Anderson was out of Yes, having been replaced by a Buggle (Trevor Horn). He had just NYC put out a solo album Song of Seven and also his first collaboration with Vangelis Short Stories in my IAR, diploma in opinion their best record together. Naturally it was time to go on tour... audio recording and music On Live in Sheffield 1980 we get a very good show, well recorded, of what Jon Anderson was doing at production, less that time. A number of his solo tracks, some from the Jon and Vangelis Short Stories album and a long than a year Yes medley featuring mostly their song based material ("Nous sommes du soleil" section, "Wonderous audioschool.com Stories"...). As a bonus, on the second CD, we get about 40 minutes of tour rehersals. -

Jon Anderson Dalai Angolul, Magyarul Jon Anderson`S Songs in English and in Hungarian

Szerény kísérlet az elveszett harmónia megtalálására Modest attempt to find the lost harmony Jon Anderson dalai angolul, magyarul Jon Anderson`s songs in English and in Hungarian 1 Jon Anderson 2 Table of Contents Tartalomjegyzék So Far Away, So Clear - Oly messzi, oly tiszta (1975)______________________________ 4 Olias of Sunhillow (1976)____________________________________________________ 5 Short Stories - Novellák (1980) ______________________________________________ 12 Song of Seven – A hét dala (1980) ____________________________________________ 20 The Friends Of Mr. Cairo – Kairo úr barátai (1981) _____________________________ 32 Animation – Mozgatás (1982) _______________________________________________ 33 ¤ 3ULYDW &ROOHFWLR ¡£¢ 0DJiQJ\&MWHPpQ __________________________________ 34 Three Ships - Három hajó (1985) ____________________________________________ 41 In The City Of Angels - Az angyalok városában (1988) ___________________________ 53 "LOVED BY THE SUN"(A NAP SZERETTE) ____________________________________ 73 Requiem For The Americas - Rekviem az amerikaiakért (1989) ____________________ 74 Page Of Life - Az élet oldala (1991) ___________________________________________ 78 Close To The Hype – Közel a feldobott állapothoz (1992)__________________________ 81 Dream - Álom (1992) ______________________________________________________ 82 Change We Must - Meg kell változnunk (1994) _________________________________ 87 Deseo (1994) ____________________________________________________________ 105 ¦ §©¨ ¦ ¦ ,WC¥ $ERX 7LP (OM| D LG -

Sheet Music (Unclassified)

SHEET MUSIC (UNCLASSIFIED) A Beautiful Friendship A Touch of the Blues A Certain Smile 'A' Train A Christmas Song A Walkin Miracle A Day in the Life of a Fool A Whistlin' Kettle & a Dancing Cat A Dream is a Wish your Heart Makes A White Sports Coat & a Pink Carnation A Fine Romance A Windmill in Old Amsterdam A Foggy Day A Woman in Love A Garden in the Rain A Wonderful Day like Today A Good Idea Son A Wonderful Guy A Gordon for Me A World of ou Own A Hard Day's Night A You're Adorable A Horse with no Name Abide with Me A Hunting We Will Go Abie my Boy A Kiss in the Dark About a Quarter to Nine A Little bit More AC/DC A Little Bitty Tear Accentuate the Positive A Little Co-operation from you Accordionist A Little Girl from Little Rock Ace of Hearts A Little in Love Across the Alley from the Alamo A Little Kiss Each Morning Across the Alley from the Alamo A Little Love A Little Kiss Across the Great Divide A Little on the Lonely Side Across the Universe A Long & Lasting Love Act Naturally A Loser with nothing to loose Adagio from Sonata Pathetique A Lot of Livin' to Do Addicted to Love A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening Adios A Man & A Woman Adios Amor A Man Chases a Girl Adios Muchachos A Man without Love African Waltz A Marshmallow World After the Ball A Million Miles from Nowhere After the Love has Gone A Night in Tunisia After the Rain A Nightingale Sang in Berkely Square After You've Gone A Paradise for Two Agadoo A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody Again A Rockin' Good Way Agatha Christies Poirot A Root'n Toot'n Santa Claus Ah So Pure A -

VANGELIS the Collection

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] VANGELIS The Collection Er ist der Elektronikpionier schlechthin und machte den Synthesizer in der Popmusik hoffähig. Er veröffentlichte Hits, die um die Welt gingen, schrieb kultige Musik zu kultigen Filmen und schrieb mit Conquest of Paradise die Hymne des Boxers Henry Maske, die zu einem Riesenhit wurde. Wann immer große Emotionen im Spiel sind, ist es Zeit für VANGELIS. Auch bei den jüngst abgeschlossenen Olympischen Spielen 2012 stand eine seiner Kompositionen an zentraler Stelle: Chariots of Fire wurde nicht nur vom London Symphony Orchestra zur Eröffnung gespielt, sondern bildete auch die musikalische Untermalung für die Medaillenverleihung - eine perfekte Wahl, zumal der Film „Die Stunde des Siegers“, aus dem das Stück stammt, die olympischen Spiele des Jahres 1924 zum Thema hat. VANGELIS ist ein Genie, dessen Schaffen aus der Musikwelt nicht mehr wegzudenken ist. Er gilt vielen als innovativster und genialster Musiker der modernen Musik und ist als Komponist, Filmkomponist und Produzent so gefragt, dass sein Repertoire nicht auf zwei DIN-A-4-Seiten passt. Rhino Records veröffentlicht nun eine spektakuläre Sammlung seiner besten Tracks auf 2 CDs mit dem Titel VANGELIS - The Collection. Das eindrucksvolle Repertoire enthält durchweg Highlights, darunter Tracks aus Ridley Scotts Kultfilm Blade Runner von 1982, der bis heute als einer der besten Science Fiction-Filme aller Zeiten gilt. Zu einem musikalischen Weltkulturerbe wurde auch der mehrfach mit Platin ausgezeichnete Filmscore zu 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (dt: „1492 - Die Eroberung des Paradieses“), eine der gelungensten Verfilmungen der Entdeckung Amerikas durch Columbus. -

Polydor Records Discography 3000 Series

Polydor Records Discography 3000 series 25-3001 - Emergency! - The TONY WILLIAMS LIFETIME [1969] (2xLPs) Emergency/Beyond Games//Where/Vashkar//Via The Spectrum Road/Spectrum//Sangria For Three/Something Special 25-3002 - Back To The Roots - JOHN MAYALL [1971] (2xLPs) Prisons On The Road/My Children/Accidental Suicide/Groupie Girl/Blue Fox//Home Again/Television Eye/Marriage Madness/Looking At Tomorrow//Dream With Me/Full Speed Ahead/Mr. Censor Man/Force Of Nature/Boogie Albert//Goodbye December/Unanswered Questions/Devil’s Tricks/Travelling PD 2-3003 - Revolution Of The Mind-Live At The Apollo Volume III - JAMES BROWN [1971] (2xLPs) Bewildered/Escape-Ism/Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved/Get Up I Feel Like Being A Sex Machine/Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose/Hot Pants (She Got To Use What She Got To Need What She Wants)/I Can’t Stand It/I Got The Feelin’/It’s A New Day So Let A Man Come In And Do The Popcorn/Make It Funky/Mother Popcorn (You Got To Have A Mother For Me)/Soul Power/Super Bad/Try Me [*] PD 2-3004 - Get On The Good Foot - JAMES BROWN [1972] (2xLPs) Get On The Good Foot (Parts 1 & 2)/The Whole World Needs Liberation/Your Love Was Good For Me/Cold Sweat//Recitation (Hank Ballard)/I Got A Bag Of My Own/Nothing Beats A Try But A Fail/Lost Someone//Funky Side Of Town/Please, Please//Ain’t It A Groove/My Part-Make It Funky (Parts 3 & 4)/ Dirty Harri PD 2-3005 - Ten Years Are Gone - JOHN MAYALL [1973] (2xLPs) Ten Years Are Gone/Driving Till The Break Of Dawn/Drifting/Better Pass You By//California Campground/Undecided/Good Looking -

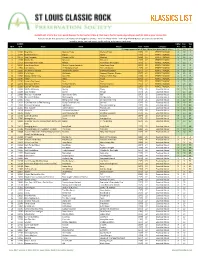

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Those Were the Days Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THOSE WERE THE DAYS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK OBE Sir Terry Wogan | 352 pages | 08 Oct 2015 | Pan MacMillan | 9781447298250 | English | London, United Kingdom Those Were the Days PDF Book Everything felt heavy and lethargic. Colgate-Palmolive, CBS. Irish Singles Chart. Japan Oricon Singles Chart [26]. Ultratop Hit Parade Italia. Today's Top Stories. Freaks were in a circus tent. I woke up some time later in a different episode of "Chopped", and suddenly, my body was not my own. The non-English sets of lyrics were also recorded by Dalida and Sandie Shaw , with Shaw recording the English lyrics as well. A perfume magnate hires Marlowe to find his secretary. Georgian singer Tamara Tsereteli — and Russian singer Alexander Vertinsky made what were probably the earliest recordings of the song, in [4] and in [5] respectively. Preston, who goes undercover aboard a riverboat to track down a killer. Norman Brokenshire announces. Cast includes Paul Hughes as Mr. Casey acts as a decoy to trap a murderous hitch-hiker. Guys like us, we had it made. Texaco, CBS. You'll have to wait till next week to hear all about why Peter took the kids for two weekends in a row. After all, the celebration traditionally starts at midnight the night of Oct. McGee is invited to appear on a radio show and play some of his old records. I know single Moms and single Dads do this stuff every day, but it sure is crummy when it happens. Ozzie remembers a Christmas when his father promised snow. Italy FIMI [25]. US Billboard Easy Listening [35]. -

Smash Hits Volume 31

frs^vi Februar SON ALBUMS T , -V- ! W — I'm hypnotised the I He got a bike by m A motorbike — I got the hots for a drive up t. He like the beat — I got the beat I He like the heat — I got the beat He like the beat — I got the motorbike beat I Chorus y My favourite treat on the motorbike seat Is me and Mr CC He gotta drive — When I arrive you can hear the wheels ^ squeal He is alive — I got the feel for some mean steel appeal f P He got the steel — The squeal appeal ^ He got the feel — The steel appeal P He got the steel — I got the motorbike beat ta Repeat chorus \ But shouldn't we slow down, we're heading for >town i:*:i*»i*"**^^'- On the motorbike ^ Right — give it a kick then I drive it away ^ He flash alright — Ride in the night and I sleep in the day He bike away — Take it away 1 He ride away — I gotta say r He gotta say — I got the motorbike beat J Repeat chorus I Overtake all the creeps I When we go down the street r Me and Mr CC I Words and music by Eugene Reynolds/Fay Fife ' Ltd J Reproduced by permission Dinsong U-' MOTORBIKE BEAT Feb 7-Feb 20 1980 Vol 2 No. 3 The Revillos 2 First of all, for all you puzzled Police fans who are wondering LIVING BY NUMBERS where Stewart Copeland and New Musik 4 Andy Summers got to in this THE PLASTIC issue — relax. -

L !Boomwhitsoftheworld for JAPANESE MARKET Copyright 1980, Billboard Publications, Inc

82 Inlernalional l !boomwHitsOFTheWorld FOR JAPANESE MARKET Copyright 1980, Billboard Publications, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical. photocopying. recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. View Polystar Plan 29 24 20 GOLDEN GREATS, Diana Ross, 7 6 IF I SAID YOU HAD A BEAUTIFUL BRITAIN Motown BODY, Bellamy Brothers, Warner (Courtesy of Music Week) 30 29 DISCOVERY, Electric Light Bros. As of 2/9/80 Orchestra, Jet As '80s Blueprint? 8 9 GREAT BALLS OF FIRE, Nightmare, SINGLES 31 27 TUSK, Fleetwood Mac, Warner Bros. Bullet This Last 32 21 EAT TO THE BEAT, Blondie, 9 8 CARAVAN SONG, Barbra Dickson, Continued from page 81 First option for U.S. release of the Week Week Chrysalis Epic Polystar will be involved with new firm's 1 1 TOO MUCH TOO YOUNG, Specials, inter- Japanese acts goes to 33 NEW STRING OF HITS, Shadows, EMI 10 NEW BABE, Styx, A&M 2 -Tone 34 33 KENNY ROGERS SINGLES ALBUM, national product as the Japanese li- Casablanca; elsewhere, to other (yet 2 10 COWARD OF THE COUNTY, Kenny United Artists censee for Casablanca Records (Bill- undecided) Polygram labels. Rogers, United Artists ITALY 35 28 ASTAIRE, Peter Skellern, Mercury (Courtesy Germano Ruscitto) 3 4 I'M IN THE MOOD FOR DANCING, board, Dec. 22, 1979). This is Prime act with overseas potential 36 NEW CORNERSTONE, Styx, A &M As of 2/5/80 Nolan Sisters, Epic effective April 1, after the U.S. -

2021 Children's Sabbath

LESSON PLANS 2021 Children’s Sabbath Lesson Plans Preschool through High School When and How to Use the Children’s Sabbath Lesson Plans The following Children's Sabbath lesson plans are designed for a one-hour class. They are presented in age-graded plans (preschool; early elementary; older elementary; middle school; and high school/youth group). However, they may be combined or adapted to be most appropriate for your classes. (Educational session plans for adults will be posted separately on CDF’s website.) The lesson plans may be used in a variety of ways: l Use the lesson plans instead of your regular curriculum the week before (preferably) or the week of the Children’s Sabbath l Weave parts of the lessons into your regular curriculum l Use the lessons during a special Children’s Sabbath education session before (preferably) or on the Children’s Sabbath weekend—in age-graded groups or combined for a multi-age or intergenerational gathering l Use the lesson plans on a weekend or weeknight preceding the Children’s Sabbath All of the lesson plans use the same biblical passage, Psalm 31. If your church has a multi-age Sunday school class, you can combine elements of several lesson plans to meet the needs of your students. Sharing Creative Outcomes of the Children’s Sabbath Lessons You are encouraged to consider using these lesson plans for the week before the congregation celebrates the Children’s Sabbath. Each lesson plan includes a creative response by the students that is designed to be shared with the adults of the congregation during worship or fellowship time.