Amerikastudien / American Studies 66.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Liberty Actions Taken by Trump Administration 2017 on May

Religious Liberty Actions Taken By Trump Administration 2017 ● On May 4, 2017, President Trump signed an executive order that ensures religious organizations are protected from discrimination. ● In October 2017, the Trump administration announced that the U.S. will provide direct assistance to persecuted Christians in the Middle East. 2018 ● On January 2, 2018, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) announced changes in federal disaster funding that would include private non-profit houses of worship. ● In January 2018, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced the formation of a Conscience and Religious Freedom Division within the HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR). The purpose of the division is to "restore federal enforcement of our nation's laws that protect the fundamental and unalienable right of conscience and religious freedom." ● In January 2018, the Justice Department designated a new section in the U.S. Attorney’s Manual specifically devoted to the protection of religious liberty. The section, entitled The "Associate Attorney General’s Approval and Notice Requirements for Issues Implicating Religious Liberty" will require all U.S. Attorney Offices to set up a point of contact for any civil suit involving religious freedom or liberty. ● In May 2018, President Trump signed an executive order to establish a White House Faith and Opportunity Initiative. The Initiative would "provide recommendations on the Administration’s policy agenda affecting faith based and community programs; provide recommendations on programs and policies where faith-based and community organizations may partner and/or deliver more effective solutions to poverty; apprise the Administration of any failures of the executive branch to comply with religious liberty protections under law; and reduce the burdens on the exercise of free religion." ● On July 30, 2018, U.S. -

Civil Service Professionalisation in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine

CIVIL SERVICE PROFESSIONALISATION IN ARMENIA, AZERBAIJAN, GEORGIA, MOLDOVA AND UKRAINE November 2014 Salvador Parrado 2 Rue André Pascal This SIGMA Paper has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. SIGMA Papers should not be 75775 Paris Cedex 16 reported as representing the official views of the EU, the OECD or its member countries, or of beneficiaries participating in the France SIGMA Programme. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the author(s). SIGMA Papers describe preliminary results or research in progress by the author(s) and are published to stimulate discussion on mailto:[email protected] a broad range of issues on which the EU and the OECD work. Comments on Working Papers are welcomed, and may be sent to Tel: +33 (0) 1 45 24 82 00 SIGMA-OECD, 2 rue André-Pascal, 75775 Paris Cedex 16, France. Fax: +33 (0) 1 45 24 13 05 This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the www.sigmaweb.org delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 5 The scope of the civil service ....................................................................................................................... 5 The institutional set-up for consistent and effective human resource management practices ................ -

Restored Republic Via a GCR As of Jan

Click here if you'd like to Donate to THE NEAL SHOW - THANKS !! Click here to see PAST SHOWS or get the Newsletter ~ Please share this with friends who may be interested ~ lkjlkjlj THE NEAL SHOW ~Community, Architecture and the Individual~ *** You can email me at [email protected] if you would like to be added to the list of subscribers to this newsletter. !! THE NEAL SHOW !! For the time being, I will be pre-recording shows and mounting them on the “PAST SHOWS” menu item you will see in the upper right hand corner of the "nealshow.com" website. I hope to have shows posted for you by Saturday between 1:00 and 4:00 PM. THIS IS THE TEMPORARY LINK TO ALL SHOWS FROM THIS DATE FORWARD. {{ http://www.nealshow.com/page/past_shows }} *** “My judgment is not delayed for I sit upon my throne each day and I bless and I punish, but the fullness of my wrath shall not come until the days when darkness declares itself victor and when my harvest of mercy has been a blessing unto the inhabitants of all the earth. In my hand is a cup and this means that my punishment has already been established and prepared and it will not be stayed and it will not pass. I will pour out my wrath upon the ones who seek darkness and walk therein and my wrath shall also be unto all who support the ways of 1 darkness and those who strive against light and truth. Look unto me and trust in me and understand that those who see the rainbow must also endure the storm.” ~David Nix *** Humility is the key to finding god. -

Did Trump Incite the Riots?

Did Trump incite the riots? Only with the help of Big Tech Campaigning group SumOfUs has reviewed dozens of social media accounts, pages, and groups, as well as far-right disinformation websites, and has found several key incidents that highlight how Trump used social media to rally his base in support of the events that took place on January 6, and how the power of Trump’s tweets and retweets - sometimes of obscure pro-Trump accounts - escalated to the use of violence. From the evidence, it is clear that while Trump lit the match that set this violent far-right movement ablaze, it was tech companies that provided the platforms for organizing — and their policies, algorithms, and tools directly fueled it. The briefing reveals how tech platforms responded, and how the measures they took came up massively short in preventing the escalation of violence. It also highlights how ad tech platforms like Google and Amazon are profiting off of disinformation websites — which are in turn amplified on Facebook and continue to circulate in far-right extremist networks. In addition to holding Donald Trump to account for his role in the insurrection, SumOfUs urges lawmakers to launch an official investigation into the role tech companies played in aiding and abetting the insurrection, as well as the role Facebook’s algorithmic amplification played in boosting electoral disinformation. Trump: the Internet’s firehose of disinformation President Trump’s tweet about ballot harvesting, April 14, 2020 Responsibility for content casting skepticism about the election lies first and foremost with Donald Trump. Early in the spring, roughly 200 days before the election, Trump tweeted that mail-in ballots are rampant with fraud. -

The True Story of 'Mrs. America' | History | Smithsonian Magazine 4/16/20, 9�07 PM the True Story of ‘Mrs

The True Story of 'Mrs. America' | History | Smithsonian Magazine 4/16/20, 907 PM The True Story of ‘Mrs. Americaʼ In the new miniseries, feminist history, dramatic storytelling and an all-star-cast bring the Equal Rights Amendment back into the spotlight Cate Blanchett plays conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly (Sabrina Lantos / FX) By Jeanne Dorin McDowell smithsonianmag.com April 15, 2020 It is 1973, and conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly and feminist icon Betty https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/true-story-mrs-america-180974675/ Page 1 of 11 The True Story of 'Mrs. America' | History | Smithsonian Magazine 4/16/20, 907 PM Friedan trade verbal barbs in a contentious debate over the Equal Rights Amendment at Illinois State University. Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique and “the mother of the modern womenʼs movement,” argues that a constitutional amendment guaranteeing men and women equal treatment under the law would put a stop to discriminatory legislation that left divorced women without alimony or child support. On the other side, Schlafly, an Illinois mother of six who has marshalled an army of conservative housewives into an unlikely political force to fight the ERA, declares American women “the luckiest class of people on earth.” Then Schlafly goes for the jugular. “You simply cannot legislate universal sympathy for the middle-aged woman,” she purrs, knowing that Friedan had been through a bitter divorce. “You, Mrs. Friedan, are the unhappiest women I have ever met.” “You are a traitor to your sex, an Aunt Tom,” fumes Friedan, taking the bait. “And you are a witch. God, Iʼd like to burn you at the stake!” Friedanʼs now-infamous rejoinder is resurrected in this fiery exchange in “Mrs. -

The Alt-Right Comes to Power by JA Smith

USApp – American Politics and Policy Blog: Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith Page 1 of 6 Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt- Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith J.A Smith reflects on two recent books that help us to take stock of the election of President Donald Trump as part of the wider rise of the ‘alt-right’, questioning furthermore how the left today might contend with the emergence of those at one time termed ‘a basket of deplorables’. Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Storming of the Presidency. Joshua Green. Penguin. 2017. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. Angela Nagle. Zero Books. 2017. Find these books: In September last year, Hillary Clinton identified within Donald Trump’s support base a ‘basket of deplorables’, a milieu comprising Trump’s newly appointed campaign executive, the far-right Breitbart News’s Steve Bannon, and the numerous more or less ‘alt right’ celebrity bloggers, men’s rights activists, white supremacists, video-gaming YouTubers and message board-based trolling networks that operated in Breitbart’s orbit. This was a political misstep on a par with putting one’s opponent’s name in a campaign slogan, since those less au fait with this subculture could hear only contempt towards anyone sympathetic to Trump; while those within it wore Clinton’s condemnation as a badge of honour. Bannon himself was insouciant: ‘we polled the race stuff and it doesn’t matter […] It doesn’t move anyone who isn’t already in her camp’. -

Jay-Richards-Longer

Jay W. Richards, Ph.D., is author of many books including the New York Times bestsellers Infiltrated (2013) and Indivisible (2012). He is also the author of Money, Greed, and God, winner of a 2010 Templeton Enterprise Award; and co-author of The Privileged Planet with astronomer Guillermo Gonzalez. Richards is an Assistant Research Professor in the School of Business and Economics at The Catholic University of America and a Senior Fellow at the Discovery Institute. In recent years he has been Distinguished Fellow at the Institute for Faith, Work & Economics, Contributing Editor of The American at the American Enterprise Institute, a Visiting Fellow at the Heritage Foundation, and Research Fellow and Director of Acton Media at the Acton Institute. Richards’ articles and essays have been published in The Harvard Business Review, Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, Washington Post, Forbes, The Daily Caller, Investor’s Business Daily, Washington Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Huffington Post, The American Spectator, The Daily Caller, The Seattle Post- Intelligencer, and a wide variety of other publications. He is a regular contributor to National Review Online, Christian Research Journal, and The Imaginative Conservative. His topics range from culture, economics, and public policy to natural science, technology, and the environment. He is also creator and executive producer of several documentaries, including three that appeared widely on PBS—The Call of the Entrepreneur, The Birth of Freedom, and The Privileged Planet. Richards’ work has been covered in The New York Times (front page news, science news, and editorial), The Washington Post (news and editorial), The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Times, Nature, Science, Astronomy, Physics Today, Reuters, The Chronicle of Higher Education, American Enterprise, Congressional Quarterly Researcher, World, National Catholic Register, and American Spectator. -

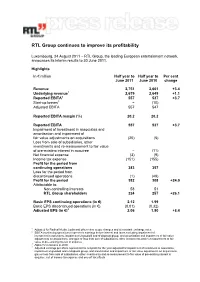

RTL Group Continues to Improve Its Profitability

RTL Group continues to improve its profitability Luxembourg, 24 August 2011 − RTL Group, the leading European entertainment network, announces its interim results to 30 June 2011. Highlights In € million Half year to Half year to Per cent June 2011 June 2010 change Revenue 2,751 2,661 +3.4 Underlying revenue1 2,679 2,649 +1.1 Reported EBITA2 557 537 +3.7 Start-up losses3 − (10) Adjusted EBITA 557 547 Reported EBITA margin (%) 20.2 20.2 Reported EBITA 557 537 +3.7 Impairment of investment in associates and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions (20) (5) Loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments and re-measurement to fair value of pre-existing interest in acquiree − (11) Net financial expense (3) (9) Income tax expense (151) (155) Profit for the period from continuing operations 383 357 Loss for the period from discontinued operations (1) (49) Profit for the period 382 308 +24.0 Attributable to: Non-controlling interests 58 51 RTL Group shareholders 324 257 +26.1 Basic EPS continuing operations (in €) 2.12 1.99 Basic EPS discontinued operations (in €) (0.01) (0.32) Adjusted EPS (in €)4 2.06 1.90 +8.4 1 Adjusted for Radical Media, Ludia and other minor scope changes and at constant exchange rates 2 EBITA (continuing operations) represents earnings before interest and taxes excluding impairment of investment in associates, impairment of goodwill and of disposal group, and amortisation and impairment of fair value adjustments on acquisitions, and gain or loss from sale of subsidiaries, other investments -

Who Supports Donald J. Trump?: a Narrative- Based Analysis of His Supporters and of the Candidate Himself Mitchell A

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2016 Who Supports Donald J. Trump?: A narrative- based analysis of his supporters and of the candidate himself Mitchell A. Carlson 7886304 University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Carlson, Mitchell A. 7886304, "Who Supports Donald J. Trump?: A narrative-based analysis of his supporters and of the candidate himself" (2016). Summer Research. Paper 271. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/271 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Mitchell Carlson Professor Robin Dale Jacobson 8/24/16 Who Supports Donald J. Trump? A narrative-based analysis of his supporters and of the candidate himself Introduction: The Voice of the People? “My opponent asks her supporters to recite a three-word loyalty pledge. It reads: “I’m With Her.” I choose to recite a different pledge. My pledge reads: ‘I’m with you—the American people.’ I am your voice.” So said Donald J. Trump, Republican presidential nominee and billionaire real estate mogul, in his speech echoing Richard Nixon’s own convention speech centered on law-and-order in 1968.1 2 Introduced by his daughter Ivanka, Trump claimed at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio that he—and he alone—is the voice of the people. -

State, Local Crime Rate Down; Violent Crimes up by PHIL ATTINGER STAFF WRITER

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Monday, June 28, 2021 VOL. 102 | NO. 179 | $1.00 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1919 An Edition Of The Sun Scooters popular; some stolen Andrews: Fail safes help find, recover lost Birds By PHIL ATTINGER There have been some, module that runs and charges had taken apart the electric STAFF WRITER however, who haven’t used them. module on the handle bars, them properly. Andrews said So far, two were recovered, Polk Sheriff’s officials said. SEBRING — The popular a handful of the scooters have from Lorida and Avon Park, Deputies there recovered the Bird Scooter has given people “walked off.” Andrews said. Another was scooter and informed the shopping in Sebring’s down- About seven users took recovered by the Polk County Sebring Police Department, COURTESY GRAPHIC/DAN town area a quicker way to visit vehicles out of Community Sheriff’s Office after Dan which had the original theft FEATHERS shops, using the electric-motor Redevelopment Agency District Feathers, who assists Andrews report. two-wheeled vehicles to get and never returned them. in managing the fleet, tracked The remaining three scooters If you want to take a Bird Scooter them around faster than their “They’re no good outside a missing one to an address ended up on the bottom of outside the downtown area, you can feet can take them. downtown,” Andrews said. off State Road 60, west of Lake Lake Jackson, no longer usable. if you hug the shores of Lake Jackson, “They are a really small That hasn’t stopped some Wales. Any permanently disabled as seen from the Bird mobile app compact scooter, think of a people from trying to make the Officials with the Polk County scooter is a $1,200 loss, which also shows some of the nearest little child’s Razor scooter, but public transit option a personal Sheriff said they found the Andrews said. -

Download Transcript

Gaslit Nation Transcript 17 February 2021 Where Is Christopher Wray? https://www.patreon.com/posts/wheres-wray-47654464 Senator Ted Cruz: Donald seems to think he's Michael Corleone. That if any voter, if any delegate, doesn't support Donald Trump, then he's just going to bully him and threaten him. I don't know if the next thing we're going to see is voters or delegates waking up with horse's heads in their bed, but that doesn't belong in the electoral process. And I think Donald needs to renounce this incitement of violence. He needs to stop asking his supporters at rallies to punch protestors in the face, and he needs to fire the people responsible. Senator Ted Cruz: He needs to denounce Manafort and Roger Stone and his campaign team that is encouraging violence, and he needs to stop doing it himself. When Donald Trump himself stands up and says, "If I'm not the nominee, there will be rioting in the streets.", well, you know what? Sol Wolinsky was laughing in his grave watching Donald Trump incite violence that has no business in our democracy. Sarah Kendzior: I'm Sarah Kendzior, the author of the bestselling books The View from Flyover Country and Hiding in Plain Sight. Andrea Chalupa: I'm Andrea Chalupa, a journalist and filmmaker and the writer and producer of the journalistic thriller Mr. Jones. Sarah Kendzior: And this is Gaslit Nation, a podcast covering corruption in the United States and rising autocracy around the world, and our opening clip was of Senator Ted Cruz denouncing Donald Trump's violence in an April 2016 interview. -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic.