Moscow's War in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education in Danger

Education in Danger Monthly News Brief December Attacks on education 2019 The section aligns with the definition of attacks on education used by the Global Coalition to Protect Education under Attack (GCPEA) in Education under Attack 2018. Africa This monthly digest compiles reported incidents of Burkina Faso threatened or actual violence 10 December 2019: In Bonou village, Sourou province, suspected affecting education. Katiba Macina (JNIM) militants allegedly attacked a lower secondary school, assaulted a guard and ransacked the office of the college It is prepared by Insecurity director. Source: AIB and Infowakat Insight from information available in open sources. 11 December 2019: Tangaye village, Yatenga province, unidentified The listed reports have not been gunmen allegedly entered an unnamed high school and destroyed independently verified and do equipment. The local town hall was also destroyed in the attack. Source: not represent the totality of Infowakat events that affected the provision of education over the Cameroon reporting period. 08 December 2019: In Bamenda city, Mezam department, Nord-Ouest region, unidentified armed actors allegedly abducted around ten Access data from the Education students while en route to their campus. On 10 December, the in Danger Monthly News Brief on HDX Insecurity Insight. perpetrators released a video stating the students would be freed but that it was a final warning to those who continue to attend school. Visit our website to download Source: 237actu and Journal Du Cameroun previous Monthly News Briefs. Mali Join our mailing list to receive 05 December 2019: Near Ansongo town, Gao region, unidentified all the latest news and resources gunmen reportedly the director of the teaching academy in Gao was from Insecurity Insight. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

Deconstructing the Coverage of the Syrian Conflict in Western Media

UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCES GRADUATE ACADEMIC STUDIES Regional Master’s Program in Peace Studies MASTER THESIS Deconstructing the Coverage of the Syrian Conflict in Western Media Case Study: The Economist ACADEMIC SUPERVISOR: STUDENT: Prof. dr Radmila Nakarada Uroš Mamić Enrollment No. 22/2015 Belgrade, 2018 1 DECLARATION OF ACADEMIC INTEGRITY I hereby declare that the study presented is based on my own research and no other sources than the ones indicated. All thoughts taken directly or indirectly from other sources are properly denoted as such. Belgrade, 31 August 2018 Uroš Mamić (Signature) 2 Content 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………..3 1.1. Statement of Problem ……………………………………………………………………… 3 1.2. Research Topic ………………………………………….........……………………..............4 1.3. Research Goals and Objectives ………………………………….………………….............6 1.4. Hypotheses ………………………………………………………..…………………………7 1.4.1. General Hypothesis ………………………………………………..………………………...7 1.4.2. Specific Hypotheses …………………………………………………………………………7 1.5. Research Methodology ………………………………………………………………….......8 1.6. Research Structure – Chapter Outline ……………………………………………………...10 2. Major Themes of the Syrian Conflict in The Economist ……………………………….12 2.1. Roots of the Conflict ……………………………………………………………………….13 2.2. Beginning of the Conflict – Protests and Early Armed Insurgency …………….................23 2.3. Local Actors …………………………………………………………………………….......36 2.3.1. Syrian Government Forces …………………………………………………………………37 2.3.2. Syrian Opposition ……………………………………………………………………….......41 -

Consejo De Seguridad Distr

Naciones Unidas S/2019/820 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 15 de octubre de 2019 Español Original: inglés Aplicación de las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) y 2449 (2018) Informe del Secretario General I. Introducción 1. El presente informe es el 63º presentado en cumplimiento de lo dispuesto en el párrafo 17 de la resolución 2139 (2014), el párrafo 10 de la resolución 2165 (2014), el párrafo 5 de la resolución 2191 (2014), el párrafo 5 de la resolución 2258 (2015), el párrafo 5 de la resolución 2332 (2016), el párrafo 6 de la resolución 2393 (2017), el párrafo 12 de la resolución 2401 (2018) y el párrafo 6 de la resolución 2449 (2018) del Consejo de Seguridad, en el último de los cuales el Consejo solicitó al Secretario General que le presentara informes, por lo menos cada 60 días, sobre la aplicación de las resoluciones por todas las partes en el conflicto en la República Árabe Siria. 2. La información que aquí figura se basa en los datos de que disponen los organismos del sistema de las Naciones Unidas y en los datos obtenidos del Gobierno de la República Árabe Siria y de otras fuentes pertinentes. Los datos facilitados por los organismos del sistema de las Naciones Unidas sobre sus entregas de suministros humanitarios corresponden a los meses de agosto y septiembre de 2019. II. Acontecimientos principales Aspectos destacados: agosto y septiembre de 2019 1. Pese al alto el fuego en Idlib anunciado por la Federación de Rusia y el Gobierno de la República Árabe Siria los días 2 y 30 de agosto, respectivamente, durante el período que abarca el informe se siguió informando de bajas civiles, incluidas las muertes confirmadas de civiles. -

The Annual Report of the Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2019

The Annual Report of the Most Notable Human Rights Violations in Syria in 2019 A Destroyed State and Displaced People Thursday, January 23, 2020 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org R200104 The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction II. Executive Summary III. Comparison between the Most Notable Patterns of Human Rights Violations in 2018 and 2019 IV. Major Events in 2019 V. Most Prominent Political and Military Events in 2019 VI. Road to Accountability; Failure to Hold the Syrian Regime Accountable Encouraged Countries in the World to Normalize Relationship with It VII. Shifts in Areas of Control in 2019 VIII. Report Details IX. Recommendations X. References I. Introduction The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-govern- mental, non-profit independent organization that primarily aims to document all violations in Syria, and periodically issues studies, research documents, and reports to expose the perpetrators of these violations as a first step to holding them accountable and protecting the rights of the victims. It should be noted that Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has relied, in all of its statistics, on the analysis of victims of the conflict in Syria, on the Syrian Network for Human Rights as a primary source, SNHR also collaborate with the Independent Inter- national Commission of Inquiry and have signed an agreement for sharing data with the Independent International and Impartial Mechanism, UNICEF, and other UN bodies, as well as international organizations such as the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. -

The Syrian Civil War: Analysis of Recent Developments by Dr. Sohail

The Syrian Civil War: Analysis of Recent Developments By Dr. Sohail Mahmood On April 7, 2018 an alleged chemical weapons attack took place in Douma, Syria in which 70 people were killed.1 Russia and the Syrian government denied using chemical weapons fight against rebels in Eastern Ghouta, Syria and its ally Russia deny any chemical attack took place - with Russia calling it a "staged thing”. The rebel Syria Civil Defense Force says more than 40 people were killed and entire families were gassed to death in the attack, which drew global outrage. President Trump blasted "that animal" Syrian President Bashar Assad and said blame also fell on Russia and Iran for supporting his regime. Prime Minister Theresa said there was "unmistakable evidence" Syria was behind the attack. “No other group could have carried this out," May said. A year ago, Syria was accused of using sarin gas in an attack in the town of Khan Shaykhun. An investigation by the U.N. and OPCW concluded the Syrian air force had used the gas in its attack, which killed almost 100.2 Assad’s position in the Syrian civil war is unassailable. He is supported by Iranian-back fighters as well as the Russian air force, has cemented his control over most of the western, more heavily populated, part of the country. Rebels and jihadist insurgents are largely contained to two areas along Syria’s northern and southern borders.3 Syria's war, now in its eighth year, has seen the opposition make gains up until Russia entered the war in support of Assad in 2015. -

No. 2 Newsmaker of 2016 Was City Manager Change Rodgers Christmas Basket Fund Are Still Being Accepted

FRIDAY 162nd YEAR • No. 208 DECEMBER 30, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 22 PAGES • 50¢ Basket Fund Donations to the William Hall No. 2 Newsmaker of 2016 was city manager change Rodgers Christmas Basket Fund are still being accepted. Each By LARRY C. BOWERS Service informed Council members of year, the fund supplies boxes of Banner Staff Writer the search process they faced. food staples to needy families TOP 10 MTAS provided assistance free of during the holiday season. The The Cleveland City Council started charge, and Norris recommended the fund, which is a 501(c)(3) charity, the 2016 calendar year with a huge city hire a consultant. This was prior is a volunteer-suppported effort. challenge — an ordeal which devel- NEWSMAKERS to the Council’s decision to hire Any funds over what is needed to oped into the No. 2 news story of the Wallace, who had also assisted with pay for food bought this year will year as voted by Cleveland Daily the city’s hiring of Police Chief Mark be used next Christmas. Banner staff writers and editors — The huge field of applicants was Gibson. Donations may be mailed to First when the city celebrated the retire- vetted by city consultant and former Council explored the possibility of Tennessee Bank, P.O. Box 3566, ment of City Manager Janice Casteel Tennessee Bureau of Investigation using MTAS and a recruiting agency, Cleveland TN 37320-3566 or and announced the hiring of new City Director Larry Wallace, of Athens, as but Norris told them she had never dropped off at First Tennessee Manager Joe Fivas. -

II. Cross Shelling Between Syrian Regular Forces and Armed Opposition Groups

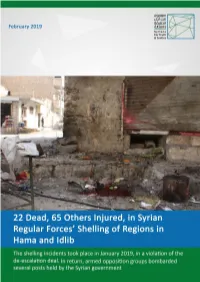

22 Dead, 65 Others Injured, in Syrian Regular Forces’ Shelling of Regions in Hama and Idlib www.stj-sy.com 22 Dead, 65 Others Injured, in Syrian Regular Forces’ Shelling of Regions in Hama and Idlib The shelling incidents took place in January 2019, in a violation of the de-escalation deal. In return, armed opposition groups bombarded several posts held by the Syrian government Page | 2 22 Dead, 65 Others Injured, in Syrian Regular Forces’ Shelling of Regions in Hama and Idlib www.stj-sy.com In southern rural Idlib and northern rural Hama1, several regions witnessed a rising tempo of the Syrian regular forces and their Russian ally’s shelling in January 2019, for the regions have endured almost daily shelling that on numerous cases targeted civilian areas, leading to the death of no less than 22 persons, women and children included, and the injury of about 65 others. The shelling that targeted the city of Maarrat al-Nu'man, Idlib, is, however, considered the most violent, where the toll rose to 11 dead civilians and 35 injured others. On the other side, armed opposition groups bombarded several Syrian regular forces-held posts in Hama, responding to the latter’s violation of the de-escalation deal, according to testimonies obtained by Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ. I. Shelling of Southern Rural Idlib: STJ’s field researchers monitored attacks on no less than 16 towns and cities, which have been targeted with artillery, missile and aerial shelling by the Syrian regular forces and the Russian forces in January 2019. -

Aleppo and the State of the Syrian War

Rigged Cars and Barrel Bombs: Aleppo and the State of the Syrian War Middle East Report N°155 | 9 September 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Pivotal Autumn of 2013 ............................................................................................. 2 A. The Strike that Wasn’t ............................................................................................... 2 B. The Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant: from “al-Dowla” to “Daesh” .................... 4 C. The Regime Clears the Way with Barrel Bombs ........................................................ 7 III. Between Hammer and Anvil ............................................................................................ 10 A. The War Against Daesh ............................................................................................. 10 B. The Regime Takes Advantage .................................................................................... 12 C. The Islamic State Bides Its Time ............................................................................... 15 IV. A Shifting Rebel Spectrum, on the Verge of Defeat ........................................................ -

International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Violations in Syria

Helpdesk Report International humanitarian law and human rights violations in Syria Iffat Idris GSDRC, University of Birmingham 5 June 2017 Question Provide a brief overview of the current situation with regard to international humanitarian law and human rights violations in Syria. Contents 1. Overview 2. Syrian government and Russia 3. Armed Syrian opposition (including extremist) groups 4. Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) 5. Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) 6. International coalition 7. References The K4D helpdesk service provides brief summaries of current research, evidence, and lessons learned. Helpdesk reports are not rigorous or systematic reviews; they are intended to provide an introduction to the most important evidence related to a research question. They draw on a rapid desk-based review of published literature and consultation with subject specialists. Helpdesk reports are commissioned by the UK Department for International Development and other Government departments, but the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of DFID, the UK Government, K4D or any other contributing organisation. For further information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Overview All parties involved in the Syrian conflict have carried out extensive violations of international humanitarian law and human rights. In particular, all parties are guilty of targeting civilians. Rape and sexual violence have been widely used as a weapon of war, notably by the government, ISIL1 and extremist groups. The Syrian government and its Russian allies have used indiscriminate weapons, notably barrel bombs and cluster munitions, against civilians, and have deliberately targeted medical facilities and schools, as well as humanitarian personnel and humanitarian objects. -

Timeline of International Response to the Situation in Syria

Timeline of International Response to the Situation in Syria Beginning with dates of a few key events that initiated the unrest in March 2011, this timeline provides a chronological list of important news and actions from local, national, and international actors in response to the situation in Syria. Skip to: [2012] [2013] [2014] [2015] [2016] [Most Recent] Acronyms: EU – European Union PACE – Parliamentary Assembly of the Council CoI – UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria of Europe FSA – Free Syrian Army SARC – Syrian Arab Red Crescent GCC – Gulf Cooperation Council SASG – Special Adviser to the Secretary- HRC – UN Human Rights Council General HRW – Human Rights Watch SES – UN Special Envoy for Syria ICC – International Criminal Court SOC – National Coalition of Syrian Revolution ICRC – International Committee of the Red and Opposition Forces Cross SOHR – Syrian Observatory for Human Rights IDPs – Internally Displaced People SNC – Syrian National Council IHL – International Humanitarian Law UN – United Nations ISIL – Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant UNESCO – UN Educational, Scientific and ISSG – International Syria Support Group Cultural Organization JSE – UN-Arab League Joint Special Envoy to UNGA – UN General Assembly Syria UNHCR – UN High Commissioner for LAS – League of Arab States Refugees NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organization UNICEF – UN Children’s Fund OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of UNRWA – UN Relief Works Agency for Humanitarian Affairs Palestinian Refugees OIC – Organization of Islamic Cooperation UNSC – UN Security Council OHCHR – UN Office of the High UNSG – UN Secretary-General Commissioner for Human Rights UNSMIS – UN Supervision Mission in Syria OPCW – Organization for the Prohibition of US – United States Chemical Weapons 2011 2011: Mar 16 – Syrian security forces arrest roughly 30 of 150 people gathered in Damascus’ Marjeh Square for the “Day of Dignity” protest, demanding the release of imprisoned relatives held as political prisoners.