A Primer on Network Neutrality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Law Made Silicon Valley

Emory Law Journal Volume 63 Issue 3 2014 How Law Made Silicon Valley Anupam Chander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Anupam Chander, How Law Made Silicon Valley, 63 Emory L. J. 639 (2014). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol63/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANDER GALLEYSPROOFS2 2/17/2014 9:02 AM HOW LAW MADE SILICON VALLEY Anupam Chander* ABSTRACT Explanations for the success of Silicon Valley focus on the confluence of capital and education. In this Article, I put forward a new explanation, one that better elucidates the rise of Silicon Valley as a global trader. Just as nineteenth-century American judges altered the common law in order to subsidize industrial development, American judges and legislators altered the law at the turn of the Millennium to promote the development of Internet enterprise. Europe and Asia, by contrast, imposed strict intermediary liability regimes, inflexible intellectual property rules, and strong privacy constraints, impeding local Internet entrepreneurs. This study challenges the conventional wisdom that holds that strong intellectual property rights undergird innovation. While American law favored both commerce and speech enabled by this new medium, European and Asian jurisdictions attended more to the risks to intellectual property rights holders and, to a lesser extent, ordinary individuals. -

Register.Com, Inc., Plaintiff-Appellee V. Verio, Inc., Defendant-Appellant

Page 1 LEXSEE 356 F.3D 393 REGISTER.COM, INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, v. VERIO, INC., Defendant-Appellant. Docket No. 00-9596 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT 356 F.3d 393; 2004 U.S. App. LEXIS 1074; 69 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1545 January 21, 2001, Argued January 23, 2004, Decided PRIOR HISTORY: [**1] Appeal by defendant Verio, Inc. from preliminary injunction granted by the United OPINION BY: LEVAL States District Court for the Southern District of New York (Jones, J.) on motion of plaintiff Register.com, OPINION: [*395] LEVAL, Circuit Judge: Inc., a registrar of Internet domain names. The order en- Defendant, Verio, Inc. ("Verio") appeals from an or- joined the defendant from using the plaintiff's mark in der of the United States District Court for the Southern communications with prospective customers, accessing District of New York (Barbara S. Jones, J.) granting the plaintiff's computers by use of software programs per- motion of plaintiff Register.com, Inc. ("Register") for a forming multiple automated, successive queries, and preliminary injunction. The court's order enjoined Verio using contact information relating to recent registrants of from (1) using Register's trademarks; (2) representing or Internet domain names ("WHOIS information") obtained otherwise suggesting to third parties that Verio's services from plaintiff's computers for mass solicitation. Regis- have the sponsorship, endorsement, or approval of Regis- ter.com, Inc. v. Verio, Inc., 126 F. Supp. 2d 238, 2000 ter; (3) accessing Register's computers by use of auto- U.S. Dist. LEXIS 18846 (S.D.N.Y., 2000) mated software programs performing multiple successive queries; and (4) using data obtained from Register's da- DISPOSITION: Affirmed. -

Free Speech Savior Or Shield for Scoundrels: an Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 43 Number 2 Article 1 1-1-2010 Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act David S. Ardia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David S. Ardia, Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, 43 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 373 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol43/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE SPEECH SAVIOR OR SHIELD FOR SCOUNDRELS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF INTERMEDIARY IMMUNITY UNDER SECTION 230 OF THE COMMUNICATIONS DECENCY ACT David S. Ardia * In the thirteen years since its enactment, section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has become one of the most important statutes impacting online speech, as well as one of the most intensely criticized. In deceptively simple language, its provisions sweep away the common law's distinction between publisher and distributor liability, granting operators of Web sites and other interactive computer services broad protectionfrom claims based on the speech of third parties. Section 230 is of critical importance because virtually all speech that occurs on the Internet is facilitated by private intermediaries that have a fragile commitment to the speech they facilitate. -

Enron Corporation Managing Energy and Information

United States of America Securities Utilities Enron Corporation Managing energy and information 23 May 2000 Andre Meade +1 212 703 4464 andre_meade@ cbcm.com Bret Connor +1 212 703 4458 bret_connor@ cbcm.com adadkdXda Contents 1. Executive summary 1 2. Valuation Results 2 3. Introduction to Enron 4 4. Enron Wholesale Energy 7 5. Enron Energy Services 23 6. Gas Pipelines 28 7. Enron Broadband Services 33 8. Other businesses 43 9. Group level results 46 10. Valuation 49 Appendix 1: Enron wholesale assets 52 Appendix 2: Merchant plant valuation 59 Appendix 3: Global regions 63 Global Utilities Team /DNLV$WKDQDVLRX *HUDLQW$QGHUVRQ CrhqsVvyvvrSrrh pu VvyvvrHh xrvt6hy ByihyVvyvvr @ rhVvyvvr (##!&%$"&"$ (##!&%$"&'' *Qhqryhxvhuhhv5pr ihxvip *Br hvhqr 5pr ihxvip 0DUWLQ%URXJK (ULF*UDEHU/RSH] @ rhVvyvvr6hy(L Ghv6r vphVvyvvr6hy*E / V-@yrp vpv 6 trvh7 hvy8uvyr (##!&%$"&$' ( ! !&"###' *Hh vi tu5pr ihxp *r vpft hir 5pipp &KULV5RJHUV 3DXO5RJHUV @ rhVvyvvr6hy @ rhVvyvvr6hy 6 vh7rytvBr hCth DhyQ thyThv (##!&%$"&"' (##!&%$"&"% *8u v tr 5pr ihxvip *Qhy tr 5pr ihxvip %UHW&RQQRU $QGUH0HDGH VTVvyvvr6hy VTVvyvvr6hy @yrp vpvBh @yrp vpvBh ( ! !&"##$' ( ! !&"##%# *i rfp 5pipp *hq rfrhqr5pipp 23 May 2000 Enron Corporation 1. Executive summary Price: May 22, 2000 Enron is one of the largest and most innovative companies competing in the US $73.25 deregulating energy markets worldwide. It is a market leader in the US and is growing rapidly in Europe, Latin America, and Asia. We believe that its Fair Value wholesale energy business will continue to grow quickly and remain the primary US $76 (+4%) driver of earnings. We believe 2000 will be a breakout year for Enron’s retail energy services business. -

The NTT/VERIO Global IP Network

PocketCover 4/15/02 1:01 PM Page 1 Office Locations Stockbridge, GA USA Los Angeles, CA USA UTAH USA 6047 North Henry Blvd #E 707 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 4810 Orem, UT USA Stockbridge, GA 30281 Los Angeles, CA 90017 1203 North Research Way NORTHEAST ph: 770-389-7200 ph: 213-624-9346 Orem, UT 84097 ph: 801-437-0200 MASSACHUSETTS FLORIDA Napa, CA USA Boca Raton, FL USA 560 Gateway Dr. Boston, MA USA 5050 Conference Way N Napa, CA 94558 31 St. James Avenue, Suite 550 Boca Raton, FL 33431 ph: 800-226-7996 EUROPE Boston, MA 02116 ph: 561-989-8574 ph: 617-912-2200 Sacramento, CA USA FRANCE Miami, FL USA 9310 Tech Center Drive, Suite 110 Aubervillers, France Boston, MA USA 801 Brickell Ave., Suite 926 Sacramento, CA 95826 1 Summer St, 7th Floor 80 Avenue Victor Hugo Miami, FL 33131-2945 ph: 916-856-1530 Boston, MA 02110 Aubervillers, France 93300 ph: 305-789-6766 ph: 617-542-2141 San Diego, CA USA GERMANY 9530 Towne Centre Drive, Suite 150 NEW JERSEY MIDWEST Sacramento, CA 92121 Frankfurt, Germany Newark, NJ USA ph: 858-535-5200 Gervinusstrasse 18-22 165 Halsey Street, 2nd floor KANSAS Frankfurt, Germany 60322 Newark, NJ 07102 Fairways, KS USA San Francisco, CA USA 4330 Shawnee Mission Parkway, Suite 221 401 Third Street Neutraubling, Germany ph: 212-768-9455 Neugablonzer Str 1 Fairways, KS 66205 San Francisco, CA 94107 Neutraubling, Germany 93073 Princeton, NJ USA ph: 913-261-3900 ph: 415-836-7400 4390 US Route 1 North, 3rd Floor SPAIN Princeton, NJ 08540 ILLINOIS San Jose, CA USA ph: 609-514-3800 Chicago, IL USA 2334 Lundy Place Barcelona, Spain Avenida Diagonal 534, 7 350 E. -

Register.Com, Inc. V. Verio, Inc. (S.D.N.Y.)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK REGISTER.COM, INC., Plaintiff, 00 Civ 5747 (BSJ) -against- Order VERIO, INC., Defendant. BARBARA S. JONES UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE Introduction Plaintiff Register.com, a registrar of Internet domain names, moves for a preliminary injunction against the defendant, Verio, Inc. ("Verio"), a provider of Internet services. Register.com relies on claims under Section 43 (a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a); the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986, 18 U.S.C. § 1030, as amended; as well as trespass to chattels and breach of contract under the common law of the State of New York. In essence Register.com seeks an injunction barring Verio from using automated software processes to access and collect the registrant contact information contained in its WHOIS database and from using any of that information, however accessed, for mass marketing purposes. I. Findings of Fact The Parties Plaintiff Register.com is one of over fifty domain name registrars for customers who wish to register a name in the .com, .net, and .org top-level domains. As a registrar it contracts with these second-level domain ("SLD") name holders and a registry, collecting registration data about the SLD holder and submitting zone file information for entry in the registry database. In addition to its domain name registration services, Register.com offers to its customers, both directly and through its more than 450 co-branded and private label partners, a variety of other related services, such as (i) web site creation tools; (ii) web site hosting; (iii) electronic mail; (iv) domain name hosting; (vi) domain name forwarding, and (vi) real-time domain name management. -

Emerging Internet Oligopolies: a Political Economy Analysis

Michele Javary and Robin Mansell Emerging internet oligopolies: a political economy analysis Book section Original citation: Originally published in Mansell, Robin and Javary, Michele (2002) Emerging internet oligopolies: a political economy analysis. In: Miller, Edythe S. and Samuels, Warren J., (eds.) An Institutionalist Approach to Public Utilities Regulation. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, Michigan, pp. 162-201. ISBN 9780870136245 © 2002 Michigan State University Press This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/10442/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2014 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. 3vTrebrw.doc 20/08/2014 1:58 PM Emerging Internet Oligopolies: A Political Economy Analysis by Michele Javary and Robin Mansell * SPRU - Science and Technology Policy Research University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, East Sussex BN1 9RF, UK Email: [email protected]; [email protected] First Draft - Not for citation or distribution without the authors’ permission Chapter prepared for a volume of essays honoring Harry M Trebing, edited by Warren J Samuels and Edythe Miller, forthcoming Michigan State University Press, 2000. -

Before the Receiveo Postal Pate Commission

RECEIVEO BEFORE THE POSTAL PATE COMMISSION 6:.< 20 4 15 PEI ‘99 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20268-0001 POSTALEATE COHHIXICH OFFlCEOFTtii SECRFTARY I COMPLAINT ON POST E.C.S. Docket No. C99-1 UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE RESPONSES TO UNITED PARCEL SERVICE INTERROGATORIES UPS/USPS3(B-C), 4,11,15-17,27-28,30-31,43 46(A), 47(A-E) AND 49 (August 20,1999) In accordance with P.O. Ruling No. C99-119 and the discussion of the participants at the prehearing conference held on August 10, 1999, the United States Postal Service hereby provides compelled responses to the following interrogatories of United Parcel Service: UPS/USPS-3(b-c), 4, 15-17, 27-28, 30-31, and 43. A response to interrogatory UPS/USPS-3(a) was filed on July 20. The Postal Service requested that it be permitted to file the response to interrogatory UPS/USPS-2 under protective conditions proposed by the Postal Service in this docket. Tr. 1116-17. UPS opposed this request, Tr. 1118-19, and this issue remains outstanding. The Presiding Officer took under advisement matters relating to interrogatory UPSIUSPS-44. Tr. l/26-27. In addition, the Presiding Officer requested that UPS file an amendment to interrogatory UPSIUSPS-41. Tr. 1139. UPS withdrew interrogatory UPS/USPS-20(a) without prejudice. Tr. 1120. In the United States Postal Service Answer in Opposition to Motion of United Parcel Service to Compel United States Postal Service to Answer Interrogatories UPS/USPS46(A), 47-49, filed on August 13, the Postal Service stated that it would provide responses to interrogatories UPS/USPS46(a), 47(a-e), and 49; accordingly, responses to these interrogatories are provided as well. -

International Telecommunications Mergers: U.S

International Telecommunications Mergers: U.S. National Security Threats Inherent in Foreign Government Ownership of Controlling Interests Kathleen A. Lacey* Barbara Crutchfield George† ** Rajan George I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................30 II. BACKGROUND .....................................................................................33 III. NATIONAL SECURITY CONCERNS........................................................35 IV. DEREGULATION: SETTING THE STAGE FOR INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS MERGERS .....................................................37 A. Telecommunications Act of 1996 .............................................37 B. Multilateral Organizations.........................................................39 1. First Steps in GAT-GATT (1994) .....................................39 2. World Trade Organization (1997) ....................................39 V. L EGISLATIVE ENVIRONMENT FOR ESTABLISHING FOREIGN GOVERNMENT OWNERSHIP RESTRICTIONS.........................................41 A. Telecommunication Act (1934).................................................41 B. Exon-Florio Amendment (1988)...............................................41 1. Functions of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) ........................42 C. Byrd Amendment (1992)...........................................................43 D. Telecommunications Act (1996) ...............................................44 E. Presidential Decision Directive -

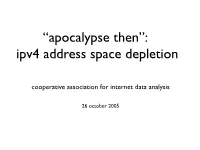

Ipv4 Address Space Depletion

“apocalypse then”: ipv4 address space depletion cooperative association for internet data analysis 26 october 2005 problem statement environmental problem: running out of addresses! solution started in 90s, but uptake slower than “expected” important connection: the research community has same problem. underlying question: how do we innovate architecturally? deeper question: how do we leave the Internet better than we found it? historical context the news gets worse. this isn’t even the data we need to inform a discussion about IPv6 uptake. what [predicting] the future needs INNOVATOR EPS ($) MKT CAP ($B) MCIW -11.22 6.5 SPRNT/NXTL -0.31 34 the numbers that will VERIO/NTT 1.98 71.6 drive our future have LEVEL3 -0.74 1.9 SBC/T 1.41 78 different units QWEST -0.45 7.7 COGENT -7.42 0.2 GLBC -13.84 0.3 SAVVIS -0.90 0.12 ABOVENET n/a n/a WILTEL n/a n/a innovation TELEGLOBE -0.74 0.2 requires C&W 0.70 4.7B TWTELCOM -1.12 1.0 capital. (TWARNER) 0.48 82 XO -2.18 0.4 source: finance.yahoo.com, 25 oct 2005 where is the capital for innovation? INNOVATOR EPS ($) MKT CAP ($B) ironically, it’s from CISCO 0.87 108 where the innovation GOOGLE 3.41 97 is happening. AMAZON 1.25 19 YAHOO 1.07 49 EBAY 0.73 51 JUNIPER 0.53 13 we’re trying to make the APPLE 1.56 47. future safe for innovation, INTEL 1.33 141 but we have to innovate VERISIGN 0.93 6.15 to do so. -

L Edward J. Malecki

The Internet: Where Does Florida Stand?l Edward J. Malecki Technology is now among the factors that make a place com petitive. State-of-the-art economic development no longer focuses on "ch'lsing" high technology companies, but has given way to building knowledge, networks, and collaboration. Newer, "fourth wave" of policies that have emerged since the mid-1990s now comprise a mix of public-sector policies to integrate local econo mies into global markets, develop local human capital resources, and increase use of tL'lecommunications as a development tool (Clarke and Caile 1998). The argumcnt that a "new economy" has developed is compel ling. The Internet has changed how people, firms, and govern nll'nts go about their daily routines. Yet the existence of a "digital divide" between havcs and have-nots is also disturbing. In a series of reports, the US Department of Commerce has documented that the poor and thosl' in rural areas are far more likely to be uncon nected to the new economy (NTIA 2000a).2 A "new geography" also is eml'rging, with some places taking better advantage of the new economic and technological situation than others (Kotkin 2(00). The paper investigates briefly where Florida stands in the Internet economy, primarily using data for 2000. This is followed bv a look at some statewide indicators. A third section examines in detail the conncctions to Florida metropolitan areas on the Intcrnet's "backbone" networks. A fourth discusses interconnec tion and the two South Florida Internet Exchange (IX) points. The last section looks at several other rankings of Florida's metro areas related to the Internet. -

Specht V. Netscape Communications Corp., 150 F

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT August Term, 2001 Argued: March 14, 2002 Decided: October 1, 2002 Docket Nos. 01-7860(L), 01-7870(CON), 01-7872(CON) _________________________________________ CHRISTOPHER SPECHT, JOHN GIBSON, MICHAEL FAGAN, SEAN KELLY, MARK GRUBER, and SHERRY WEINDORF, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. NETSCAPE COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION and AMERICA ONLINE, INC., Defendants-Appellants. __________________________________________ Before: McLAUGHLIN, LEVAL, and SOTOMAYOR, Circuit Judges. Plaintiffs in this action brought suit, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, against a provider of computer software programs and its corporate parent, alleging that a “plug-in” software program, created by defendants to facilitate Internet use and made available on defendants’ website for free downloading, invaded plaintiffs’ privacy by clandestinely transmitting personal information to the software provider when plaintiffs employed the plug-in program to browse the Internet. Defendants moved to compel arbitration and to stay court proceedings, arguing that plaintiffs’ claims were subject to an arbitration provision contained in license terms that plaintiffs allegedly had accepted when they downloaded the plug-in program. The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (Alvin K. Hellerstein, J.) denied the motion. We affirm, holding that (1) plaintiffs neither received reasonable notice of the existence of the license terms