L Edward J. Malecki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Law Made Silicon Valley

Emory Law Journal Volume 63 Issue 3 2014 How Law Made Silicon Valley Anupam Chander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj Recommended Citation Anupam Chander, How Law Made Silicon Valley, 63 Emory L. J. 639 (2014). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/elj/vol63/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory Law Journal by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHANDER GALLEYSPROOFS2 2/17/2014 9:02 AM HOW LAW MADE SILICON VALLEY Anupam Chander* ABSTRACT Explanations for the success of Silicon Valley focus on the confluence of capital and education. In this Article, I put forward a new explanation, one that better elucidates the rise of Silicon Valley as a global trader. Just as nineteenth-century American judges altered the common law in order to subsidize industrial development, American judges and legislators altered the law at the turn of the Millennium to promote the development of Internet enterprise. Europe and Asia, by contrast, imposed strict intermediary liability regimes, inflexible intellectual property rules, and strong privacy constraints, impeding local Internet entrepreneurs. This study challenges the conventional wisdom that holds that strong intellectual property rights undergird innovation. While American law favored both commerce and speech enabled by this new medium, European and Asian jurisdictions attended more to the risks to intellectual property rights holders and, to a lesser extent, ordinary individuals. -

The Great Telecom Meltdown for a Listing of Recent Titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, Turn to the Back of This Book

The Great Telecom Meltdown For a listing of recent titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, turn to the back of this book. The Great Telecom Meltdown Fred R. Goldstein a r techhouse. com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the U.S. Library of Congress. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Goldstein, Fred R. The great telecom meltdown.—(Artech House telecommunications Library) 1. Telecommunication—History 2. Telecommunciation—Technological innovations— History 3. Telecommunication—Finance—History I. Title 384’.09 ISBN 1-58053-939-4 Cover design by Leslie Genser © 2005 ARTECH HOUSE, INC. 685 Canton Street Norwood, MA 02062 All rights reserved. Printed and bound in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Artech House cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. International Standard Book Number: 1-58053-939-4 10987654321 Contents ix Hybrid Fiber-Coax (HFC) Gave Cable Providers an Advantage on “Triple Play” 122 RBOCs Took the Threat Seriously 123 Hybrid Fiber-Coax Is Developed 123 Cable Modems -

Register.Com, Inc., Plaintiff-Appellee V. Verio, Inc., Defendant-Appellant

Page 1 LEXSEE 356 F.3D 393 REGISTER.COM, INC., Plaintiff-Appellee, v. VERIO, INC., Defendant-Appellant. Docket No. 00-9596 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT 356 F.3d 393; 2004 U.S. App. LEXIS 1074; 69 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA) 1545 January 21, 2001, Argued January 23, 2004, Decided PRIOR HISTORY: [**1] Appeal by defendant Verio, Inc. from preliminary injunction granted by the United OPINION BY: LEVAL States District Court for the Southern District of New York (Jones, J.) on motion of plaintiff Register.com, OPINION: [*395] LEVAL, Circuit Judge: Inc., a registrar of Internet domain names. The order en- Defendant, Verio, Inc. ("Verio") appeals from an or- joined the defendant from using the plaintiff's mark in der of the United States District Court for the Southern communications with prospective customers, accessing District of New York (Barbara S. Jones, J.) granting the plaintiff's computers by use of software programs per- motion of plaintiff Register.com, Inc. ("Register") for a forming multiple automated, successive queries, and preliminary injunction. The court's order enjoined Verio using contact information relating to recent registrants of from (1) using Register's trademarks; (2) representing or Internet domain names ("WHOIS information") obtained otherwise suggesting to third parties that Verio's services from plaintiff's computers for mass solicitation. Regis- have the sponsorship, endorsement, or approval of Regis- ter.com, Inc. v. Verio, Inc., 126 F. Supp. 2d 238, 2000 ter; (3) accessing Register's computers by use of auto- U.S. Dist. LEXIS 18846 (S.D.N.Y., 2000) mated software programs performing multiple successive queries; and (4) using data obtained from Register's da- DISPOSITION: Affirmed. -

Free Speech Savior Or Shield for Scoundrels: an Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 43 Number 2 Article 1 1-1-2010 Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act David S. Ardia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David S. Ardia, Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, 43 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 373 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol43/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE SPEECH SAVIOR OR SHIELD FOR SCOUNDRELS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF INTERMEDIARY IMMUNITY UNDER SECTION 230 OF THE COMMUNICATIONS DECENCY ACT David S. Ardia * In the thirteen years since its enactment, section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has become one of the most important statutes impacting online speech, as well as one of the most intensely criticized. In deceptively simple language, its provisions sweep away the common law's distinction between publisher and distributor liability, granting operators of Web sites and other interactive computer services broad protectionfrom claims based on the speech of third parties. Section 230 is of critical importance because virtually all speech that occurs on the Internet is facilitated by private intermediaries that have a fragile commitment to the speech they facilitate. -

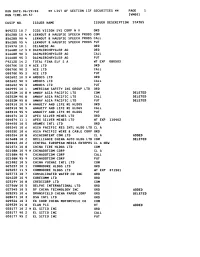

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 -

ZILLOW GROUP, INC. (Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A (Rule 14a-101) INFORMATION REQUIRED IN PROXY STATEMENT SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant ☒ Filed by a Party other than the Registrant ☐ Check the appropriate box: ☐ Preliminary Proxy Statement ☐ Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ☒ Definitive Proxy Statement ☐ Definitive Additional Materials ☐ Soliciting Material under § 240.14a-12 ZILLOW GROUP, INC. (Name of Registrant as Specified in its Charter) N/A (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if Other Than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): ☒ No fee required. ☐ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: ☐ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. ☐ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. -

PDF: 300 Pages, 5.2 MB

The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: Global Reach Emerging Ties Between the San Francisco Bay Area and India A Bay Area Council Economic Institute Report by R. Sean Randolph President & CEO Bay Area Council Economic Institute and Niels Erich Global Business/Transportation Consulting November 2009 Bay Area Council Economic Institute 201 California Street, Suite 1450 San Francisco, CA 94111 (415) 981-7117 (415) 981-6408 Fax [email protected] www.bayareaeconomy.org Rangoli Designs Note The geometric drawings used in the pages of this report, as decorations at the beginnings of paragraphs and repeated in side panels, are grayscale examples of rangoli, an Indian folk art. Traditional rangoli designs are often created on the ground in front of the entrances to homes, using finely ground powders in vivid colors. This ancient art form is believed to have originated from the Indian state of Maharashtra, and it is known by different names, such as kolam or aripana, in other states. Rangoli de- signs are considered to be symbols of good luck and welcome, and are created, usually by women, for special occasions such as festivals (espe- cially Diwali), marriages, and birth ceremonies. Cover Note The cover photo collage depicts the view through a “doorway” defined by the section of a carved doorframe from a Hindu temple that appears on the left. -

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 13F FORM 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: September 30, 2000 Check here if Amendment [ ]; Amendment Number: This Amendment (Check only one.): [ ] is a restatement. [ ] adds new holdings entries Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL GROUP, INC. Address: 70 Pine Street New York, New York 10270 Form 13F File Number: 28-219 The Institutional Investment Manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person Signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Edward E. Matthews Title: Vice Chairman -- Investments and Financial Services Phone: (212) 770-7000 Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: /s/ Edward E. Matthews New York, New York November 14, 2000 - ------------------------------- ------------------------ ----------------- (Signature) (City, State) (Date) Report Type (Check only one.): [X] 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. (Check if all holdings of this reporting manager are reported in this report.) [ ] 13F NOTICE. (Check if no holdings reported are in this report, and all holdings are reported in this report and a portion are reported by other reporting manager(s).) [ ] 13F COMBINATION REPORT. (Check -

4/Final Dst I/Iccp

Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(2005)4/FINAL Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. English DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY COMMITTEE FOR INFORMATION, COMPUTER AND COMMUNICATIONS POLICY Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(2005)4/FINAL OECD INPUT TO THE UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON INTERNET GOVERNANCE (WGIG) English - Or. English Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DSTI/ICCP(2005)4/FINAL TABLE OF CONTENTS MAIN POINTS............................................................................................................................................ 4 ICT/INTERNET-INDUCED BENEFITS .................................................................................................... 8 Leveraging ICT/the Internet in OECD countries ...................................................................................... 8 Growth in Internet usage in OECD countries........................................................................................ 8 Productivity impact and contribution to economic growth.................................................................. 10 Benefits of ICT/the Internet in non-OECD countries..............................................................................11 ICTs and development goals.............................................................................................................. -

Enron Corporation Managing Energy and Information

United States of America Securities Utilities Enron Corporation Managing energy and information 23 May 2000 Andre Meade +1 212 703 4464 andre_meade@ cbcm.com Bret Connor +1 212 703 4458 bret_connor@ cbcm.com adadkdXda Contents 1. Executive summary 1 2. Valuation Results 2 3. Introduction to Enron 4 4. Enron Wholesale Energy 7 5. Enron Energy Services 23 6. Gas Pipelines 28 7. Enron Broadband Services 33 8. Other businesses 43 9. Group level results 46 10. Valuation 49 Appendix 1: Enron wholesale assets 52 Appendix 2: Merchant plant valuation 59 Appendix 3: Global regions 63 Global Utilities Team /DNLV$WKDQDVLRX *HUDLQW$QGHUVRQ CrhqsVvyvvrSrrh pu VvyvvrHh xrvt6hy ByihyVvyvvr @ rhVvyvvr (##!&%$"&"$ (##!&%$"&'' *Qhqryhxvhuhhv5pr ihxvip *Br hvhqr 5pr ihxvip 0DUWLQ%URXJK (ULF*UDEHU/RSH] @ rhVvyvvr6hy(L Ghv6r vphVvyvvr6hy*E / V-@yrp vpv 6 trvh7 hvy8uvyr (##!&%$"&$' ( ! !&"###' *Hh vi tu5pr ihxp *r vpft hir 5pipp &KULV5RJHUV 3DXO5RJHUV @ rhVvyvvr6hy @ rhVvyvvr6hy 6 vh7rytvBr hCth DhyQ thyThv (##!&%$"&"' (##!&%$"&"% *8u v tr 5pr ihxvip *Qhy tr 5pr ihxvip %UHW&RQQRU $QGUH0HDGH VTVvyvvr6hy VTVvyvvr6hy @yrp vpvBh @yrp vpvBh ( ! !&"##$' ( ! !&"##%# *i rfp 5pipp *hq rfrhqr5pipp 23 May 2000 Enron Corporation 1. Executive summary Price: May 22, 2000 Enron is one of the largest and most innovative companies competing in the US $73.25 deregulating energy markets worldwide. It is a market leader in the US and is growing rapidly in Europe, Latin America, and Asia. We believe that its Fair Value wholesale energy business will continue to grow quickly and remain the primary US $76 (+4%) driver of earnings. We believe 2000 will be a breakout year for Enron’s retail energy services business. -

The NTT/VERIO Global IP Network

PocketCover 4/15/02 1:01 PM Page 1 Office Locations Stockbridge, GA USA Los Angeles, CA USA UTAH USA 6047 North Henry Blvd #E 707 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 4810 Orem, UT USA Stockbridge, GA 30281 Los Angeles, CA 90017 1203 North Research Way NORTHEAST ph: 770-389-7200 ph: 213-624-9346 Orem, UT 84097 ph: 801-437-0200 MASSACHUSETTS FLORIDA Napa, CA USA Boca Raton, FL USA 560 Gateway Dr. Boston, MA USA 5050 Conference Way N Napa, CA 94558 31 St. James Avenue, Suite 550 Boca Raton, FL 33431 ph: 800-226-7996 EUROPE Boston, MA 02116 ph: 561-989-8574 ph: 617-912-2200 Sacramento, CA USA FRANCE Miami, FL USA 9310 Tech Center Drive, Suite 110 Aubervillers, France Boston, MA USA 801 Brickell Ave., Suite 926 Sacramento, CA 95826 1 Summer St, 7th Floor 80 Avenue Victor Hugo Miami, FL 33131-2945 ph: 916-856-1530 Boston, MA 02110 Aubervillers, France 93300 ph: 305-789-6766 ph: 617-542-2141 San Diego, CA USA GERMANY 9530 Towne Centre Drive, Suite 150 NEW JERSEY MIDWEST Sacramento, CA 92121 Frankfurt, Germany Newark, NJ USA ph: 858-535-5200 Gervinusstrasse 18-22 165 Halsey Street, 2nd floor KANSAS Frankfurt, Germany 60322 Newark, NJ 07102 Fairways, KS USA San Francisco, CA USA 4330 Shawnee Mission Parkway, Suite 221 401 Third Street Neutraubling, Germany ph: 212-768-9455 Neugablonzer Str 1 Fairways, KS 66205 San Francisco, CA 94107 Neutraubling, Germany 93073 Princeton, NJ USA ph: 913-261-3900 ph: 415-836-7400 4390 US Route 1 North, 3rd Floor SPAIN Princeton, NJ 08540 ILLINOIS San Jose, CA USA ph: 609-514-3800 Chicago, IL USA 2334 Lundy Place Barcelona, Spain Avenida Diagonal 534, 7 350 E. -

View Annual Report

Forward >> Annual Report 2001 Internap_ Internap Network Services Corporation 2001_ Annual Report ax_ 206.264.1833 Email_ [email protected] ax_ 206.264.1833 el_ 206.441.8800 Toll-free_ 877.THE PNAP (843.7627) PNAP (843.7627) 877.THE Toll-free_ el_ 206.441.8800 T F www.internap.com o Union Square 601 Union Street Suite 1000 o Union Square 601 eattle WA 98101 98101 WA eattle S Internap Network Services Corporation Network Internap Tw Highlights >> CUSTOMERS_ COMPANY PROFILE Internap provides customers with certainty over the Internet through its patented route management technology and service guarantees. This managed 2001 974 IP service intelligently routes data across the major Internet backbones through a single connection from a customer's network to one of Internap's Service 2000 647 Points. Internap's customers bypass congestion points on the Internet, avoiding packet loss, latency and other difficulties that can plague conventional 1999 247 Internet connectivity. Founded in 1996 in Seattle, Internap offers services in numerous key markets throughout the United States, Europe and 1998 63 Japan including Amsterdam, Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, London, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, Tokyo and Washington, DC. Internap® and P-NAP® are registered trademarks of Internap. All other trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. REVENUES_ IN MILLIONS 2001 $117.4 2000 69.6 1999 12.5 1998 2.0 DIRECTORS OFFICERS Eugene Eidenberg Robert D. Shurtleff, Jr. Eugene Eidenberg Robert A. Gionesi Chairman of the Board Principal and Founder Chairman of the Board Vice President EBITDA (LOSSES)_ IN MILLIONS Chief Executive Officer S.L.