Awarua Wetlands Fire 27 October 2005 a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Policies 2015 - 2025 LONG-TERM PLAN

297 policies 2015 - 2025 LONG-TERM PLAN LONG-TERM The following policies set out basic principles and associated guidelines that Council will follow to direct and limit actions, in pursuit of its long term goal of sustainable development and providing for the current and future interests of the Community. policies 298 significance & engagement policy PURPOSE THRESHOLDS AND CRITERIA To let the Community know when and how they can A: Contribution to Community Outcomes expect to be engaged in Council’s decision-making or Key Project processes. Council will consider the extent to which the decision To act as a guide to Council and council staff as to contributes to its Community Outcomes or any key what extent, form and type of engagement is required project. If a matter clearly contributes to several from the beginning of a decision-making process. Community Outcomes or a key project and is borderline in regards to the other thresholds and To identify Council’s approach to determining the criteria for determining significance, this will mitigate significance of proposals and decisions in relation to in favour of the decision being treated as “less issues, assets, or other matters. significant”. If, however, a decision does not clearly contribute to Community Outcomes or a key project THRESHOLDS AND CRITERIA and is borderline in regards to the other thresholds GENERAL APPROACH and criteria for determining significance, Council will The decision on a matter’s significance rests with A: Contribution to Community Outcomes or Key Project adoptCouncil a willprecautionary consider the extent approach to which the and decision treat cont theributes issue to its asCommunity Outcomes or any key project. -

Policies 249

249 long term plan 2012-22 Policies The following policies set out basic principles and associated guidelines that Council will follow to direct and limit actions, in pursuit of its long term goal of sustainable development and providing for Community well-being now and into the future. policies 250 Significance Policy PURPOSE • The costs (financial and non-financial). The Invercargill City Council endeavours to be open • Implications on Council’s capacity to undertake its in its decision making, having taken into account the activities. views of its communities. The Policy on Significance • Section 97 (certain decisions to be taken only details: if provided for in the Long Term Plan), Local • The Invercargill City Council’s general approach Government Act 2002. to determining the significance of proposals The following financial thresholds are identified as and decisions in relation to issues, assets or significant: other matters that have not been included in the • Increase greater than 2% to general or targeted Annual Plan and/or Long Term Plan consultation rates for an activity. processes. • Unbudgeted expenditure of $5 million. • The thresholds and criteria to be used in • Unbudgeted annual operating cost increases in determining the extent of significance. excess of $500,000. • The Invercargill City Council's procedures for making decisions. The Invercargill City Council will use the following criteria to determine the level of significance where a • The strategic assets of the Invercargill City proposal or decision meets the significance threshold Council. test: If a proposal or decision is determined by this policy • Whether the decision flows logically and to be significant, the Council will engage and consult consequentially from a decision already with the Community before making a final decision. -

Short Walks in the Invercargill Area Invercargill the in Walks Short Conditions of Use of Conditions

W: E: www.icc.govt.nz [email protected] F: P: +64 3 217 5358 217 3 +64 9070 219 3 +64 Queens Park, Invercargill, New Zealand New Invercargill, Park, Queens Makarewa Office Parks Council City Invercargill For further information contact: information further For Lorneville Lorneville - Dacre Rd North Rd contents of this brochure. All material is subject to copyright. copyright. to subject is material All brochure. this of contents Web: www.es.govt.nz Web: for loss, cost or damage whatsoever arising out of or connected with the the with connected or of out arising whatsoever damage or cost loss, for 8 Email: [email protected] Email: responsibility for any error or omission and disclaim liability to any entity entity any to liability disclaim and omission or error any for responsibility West Plains Rd 9 McIvor Rd 5115 211 03 Ph: the agencies involved in the management of these walking tracks accept no no accept tracks walking these of management the in involved agencies the Waikiwi 9840 Invercargill While all due care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this publication, publication, this of accuracy the ensure to taken been has care due all While Waihopai Bainfield Rd 90116 Bag Private Disclaimer Grasmere Southland Environment 7 10 Rosedale Waverley www.doc.govt.nz Web: Web: www.southerndhb.govt.nz Web: Bay Rd Herbert St Findlay Rd [email protected] Email: Email: [email protected] Email: Avenal Windsor Ph: 03 211 2400 211 03 Ph: Ph: 03 211 0900 211 03 Ph: Queens Dr Glengarry Tay St Invercargill 9840 Invercargill -

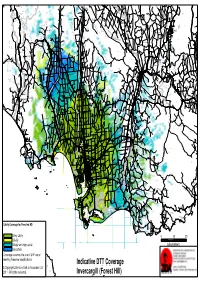

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Review of the Archaeology of Foveaux Strait, New Zealand, by Chris Jacomb, Richard Walter and Chris

REVIEW OF THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF FOVEAUX STRAIT, NEW ZEALAND CHRIS JACOMB, RICHARD WALTER and CHRIS JENNINGS University of Otago The waters and shores of Foveaux Strait make up one of the coldest, windiest environments in New Zealand and, lying well outside the tropical horticulture zone, could not have been less like the environment of the Polynesian homelands. Yet they contain an extensive archaeological record which includes a low density but wide distribution of sites, as well as some rich artefact assemblages held in private and public collections. The record is not well dated but the few radiocarbon dates and the material culture and economy suggest that occupation commenced as early there as in any other part of the country. In considering why people moved so far south so early, Lockerbie (1959) rejected push factors such as demographic or resource pressures and argued that there must have been some serious attractors (pull factors) in play. Working today with a much shorter chronology, push motives seem even less likely but it is difficult to imagine what the pull factors might have been. Foveaux Strait settlement coincides with the expansion of moa hunting in southern New Zealand but there were never many moa (Dinornithiformes) along the south coast and moa bone is rare in south coast middens. There are resident populations of sea mammals including New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsterii) and sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri) but these were not restricted to Foveaux Strait (Smith 1989: 208), nor do the sites show high levels of sea mammal predation. Today, one of the most important seasonal resources is the sooty shearwater (mutton bird or titi(Puffinus) griseus) but again, there are no strong archaeological indicators of an early emphasis on mutton birding (Anderson 1995, 2001; Sutton and Marshall 1980). -

Whakamana Te Waituna Biodiversity Plan

WHAKAMANA TE WAITUNA BIODIVERSITY PLAN R4701 WHAKAMANA TE WAITUNA BIODIVERSITY PLAN Wire rush rushland amongst mānuka shrubland, near Waituna Lagoon Road. Contract Report No. 4701 February 2019 Project Team: Kelvin Lloyd - Project management Nick Goldwater - Report author Carey Knox - Report author Helen McCaughan - Report author Steve Rate - Report author Fiona Wilcox - Report author Prepared for: Whakamana te Waituna Charitable Trust DUNEDIN OFFICE: 764 CUMBERLAND STREET, DUNEDIN 9016 Ph 03-477-2096, 03-477-2095 HEAD OFFICE: 99 SALA STREET, P.O. BOX 7137, TE NGAE, ROTORUA Ph 07-343-9017; Fax 07-343-9018, email [email protected], www.wildlands.co.nz CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. PROJECT OBJECTIVE 3 3. PROJECT SCOPE 3 4. METHODS 3 5. CULTURAL CONTEXT 4 6. ECOLOGICAL CONTEXT 5 6.1 Waituna Ecological District 5 6.2 Waterways 5 6.3 Protected Natural Areas 7 6.4 Unprotected natural areas 8 6.5 Threatened land environments 8 6.6 Vegetation and habitats 10 6.7 Overview 10 6.8 Wetland vegetation 10 6.9 Terrestrial vegetation 12 6.10 Other vegetation/habitat types 12 6.11 Naturally uncommon ecosystem types 15 7. FLORA 16 7.1 Indigenous species 16 8. FAUNA 18 8.1 Overview 18 8.2 Birds 18 8.3 Lizards 20 8.4 Aquatic fauna 23 8.5 Terrestrial invertebrates 26 9. THREATS TO ECOLOGICAL VALUES 27 9.1 Overview 27 9.2 Land-based activities 27 9.2.1 Excessive catchment inputs of sediment, nutrients, and pathogens 27 9.2.2 Indigenous vegetation clearance 27 9.2.3 Hydrological modification 27 9.2.4 Stock 28 9.2.5 Other adverse activities 28 9.3 Natural phenomena 28 9.3.1 Fire 28 9.3.2 Sea level rise 29 9.4 Effects at landscape scale 29 9.5 Pest animals and plants 29 9.5.1 Pest animals 29 9.5.2 Pest plants 30 © 2019 Contract Report No. -

CRT Conference 2020 – Bus Trips

CRT Conference 2020 – Bus Trips South-eastern Southland fieldtrip 19th March 2020 Welcome and overview of the day. Invercargill to Gorge Road We are travelling on the Southern Scenic Route from Invercargill to the Catlins. Tisbury Old Dairy Factory – up to 88 around Southland We will be driving roughly along the boundary between the Southland Plains and Waituna Ecological Districts. The Southland Plains ED is characterized by a variety of forest on loam soils, while the Waituna District is characterized by extensive blanket bog with swamps and forest. Seaward Forest is located near the eastern edge of Invercargill to the north of our route today. It is the largest remnant of a large forest stand that extended from current day Invercargill to Gorge Road before European settlement and forest clearance. Long our route to Gorge Road we will see several other smaller forest remnants. The extent of Seaward forest is shown in compiled survey plans of Theophilus Heale from 1868. However even the 1865 extent of the forest is much reduced from the original pre-Maori forest extent. Almost all of Southland was originally forest covered with the exception of peat bogs, other valley floor wetlands, braided river beds and the occasional frost hollows. The land use has changed in this area over the previous 20 years with greater intensification and also with an increase in dairy farming. Surrounding features Takitimus Mtns – Inland (to the left) in the distance (slightly behind us) – This mountain range is one of the most iconic mountains in Southland – they are visible from much of Southland. -

Policies 249

249 long term plan 2012-22 Policies The following policies set out basic principles and associated guidelines that Council will follow to direct and limit actions, in pursuit of its long term goal of sustainable development and providing for Community well-being now and into the future. policies 250 Significance Policy PURPOSE • The costs (financial and non-financial). The Invercargill City Council endeavours to be open • Implications on Council’s capacity to undertake its in its decision making, having taken into account the activities. views of its communities. The Policy on Significance • Section 97 (certain decisions to be taken only details: if provided for in the Long Term Plan), Local • The Invercargill City Council’s general approach Government Act 2002. to determining the significance of proposals The following financial thresholds are identified as and decisions in relation to issues, assets or significant: other matters that have not been included in the • Increase greater than 2% to general or targeted Annual Plan and/or Long Term Plan consultation rates for an activity. processes. • Unbudgeted expenditure of $5 million. • The thresholds and criteria to be used in • Unbudgeted annual operating cost increases in determining the extent of significance. excess of $500,000. • The Invercargill City Council's procedures for making decisions. The Invercargill City Council will use the following criteria to determine the level of significance where a • The strategic assets of the Invercargill City proposal or decision meets the significance threshold Council. test: If a proposal or decision is determined by this policy • Whether the decision flows logically and to be significant, the Council will engage and consult consequentially from a decision already with the Community before making a final decision. -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Awarua Bay-New River Estuary New Zealand EAAF NETWORK SITE CODE FOR OFFICE USE ONLY: E A A F 1 3 8 Site Information Sheet on East Asian-Australasian Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 1 of 20 Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites | Awarua Bay-New River Estuary [EAAF138] Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. -

Regional Mapping of Groundwater Denitrification Potential and Aquifer Sensitivity

Regional Mapping of Groundwater Denitrification Potential and Aquifer Sensitivity Technical Report Clint Rissmann Groundwater Scientist November 2011 Publication No 2011-12 Contents 1. Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction................................................................................................... 6 2.1. Objectives ............................................................................................................................ 6 2.2. Location and Composition of Primary Aquifers ...................................................... 7 2.2.1 General Location ................................................................................................ 7 2.2.2 Composition of Primary Aquifers .................................................................... 8 3. Redox Chemistry of Groundwaters ............................................................. 11 3.1 Background .................................................................................................................. 11 3.2 The Importance of Groundwater Redox State on Nitrate Concentration ......... 12 3.3 Controls over the Redox Status of Groundwater .................................................. 13 4. Aquifer Denitrification Potential or Sensitivity to Nitrate Accumulation .. 15 4.1 Role of Aquifer Materials in Denitrification ........................................................... 15 4.2 Assigning Denitrification Potential to Southland Aquifers -

Information on Waste/Clean up of Tiwai Point

Reference: 20210058 15 March 2021 On 15 February 2021, the Ministry for the Environment transferred the following part of your request to the Treasury: “…the latest comprehensive report MFE has (generated from whatever source) on on [sic] either of the above (waste/cleanup).” Please find enclosed the following document: Item Date Document Description Decision 1. 30 October 2020 Project 14 - Identification and Evaluation of Release in part Remediation Options I have decided to release the document listed above, subject to information being withheld under one or more of the following sections of the Official Information Act, as applicable: • personal details, under section 9(2)(a) – to protect the privacy of natural persons, including that of deceased natural persons • confidential information, under section 9(2)(ba)(i) – to protect information which is subject to an obligation of confidence or which any person has been or could be compelled to provide under the authority of any enactment, where the making available of the information would be likely to prejudice the supply of similar information, or information from the same source, and it is in the public interest that such information should continue to be supplied • legally privileged information, under section 9(2)(h) – to maintain legal professional privilege • information to carry on negotiations, under section 9(2)(j) – to carry on negotiations without prejudice or disadvantage 1 The Terrace PO Box 3724 Wellington 6140 New Zealand tel. +64-4-472-2733 https://treasury.govt.nz In making my decision, I have considered the public interest considerations in section 9(1) of the Official Information Act. -

SOUTH ISLAND HISTORICAL NOTES and SOUTHLAND COASTAL RECORDS by MAIDA BARLOW

NEW ZEALAND DOTTEREL: SOUTH ISLAND HISTORICAL NOTES AND SOUTHLAND COASTAL RECORDS By MAIDA BARLOW ABSTRACT Historical records of South Island breeding of NZ Dotterel (Charadnus obscurus) are discussed. The latest discovered South Island breeding record was 1881. No record of South Island coastal breeding was found. Numbers of birds wintering on the Southland coast declined substantially and rapidly from 1972 to 1992. The cause of decline is believed to be a decline in the Stewart Island breeding population. Colour-banded adults had allegiance to a specific wintering ground. Food items of birds at Stewart Island included 10-20 mm juvenile flounders. The current decline of NZ Dotterel in southern New Zealand (Dowding & Murphy, this issue) places a value on previously unpublished records, which are presented here. At the same time it is appropriate to comment on some previously published statements. SOUTH ISLAND COASTAL BREEDING Fleming (1982) sumrnarised early NZ Dotterel records. In September c. 1840, Earl collected a specimen in breeding plumage at Waikouaiti. It was sent to the British Museum and is illustrated in Gray (1844/45). Buller (1872) had the species "dispersed along the whole of our shores." Oliver (1930) gave no specific information on South Island breeding locations. Southland There is no record of coastal breeding on mainland Southland. George Moffett, whom I accompanied on many local field trips in the late 1940s and 1950s, had since c.1890 known of NZ Dotterel about the Southland coast, especially Awarua Bay, but knew of no breeding closer than Stewart Island. My mother, Olga Sansom, believed that, if the species bred anywhere on the Southland coast, it would be along the Tiwai Peninsula and/or the sand-dunes of Fortrose Peninsula, habitat with some similarities to the known breeding habitat at Mason Bay, Stewart Island.