On the Representations, Publishing Legacy, and Posthumous Writings of Roberto Bazlen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

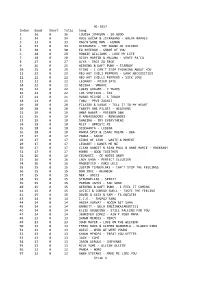

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON - SO GOOD 2 34 0 34 RUDI BUČAR & ISTRABAND - GREVA NAPREJ 3 33 0 33 RAG'N'BONE MAN - HUMAN 4 33 0 33 DISTURBED - THE SOUND OF SILENCE 5 30 0 30 ED SHEERAN - SHAPE OF YOU 6 28 0 28 ROBBIE WILLIAMS - LOVE MY LIFE 7 28 0 28 RICKY MARTIN & MALUMA - VENTE PA'CA 8 27 0 27 ALYA - SRCE ZA SRCE 9 26 0 26 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - STARBOY 10 25 0 25 STING - I CAN'T STOP THINKING ABOUT YOU 11 23 0 23 RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS - DARK NECESSITIES 12 22 0 22 RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS - SICK LOVE 13 22 0 22 LEONART - POJEM ZATE 14 22 0 22 NEISHA - VRHOVI 15 22 0 22 LUKAS GRAHAM - 7 YEARS 16 22 0 22 LOS VENTILOS - ČAS 17 21 0 21 RUSKO RICHIE - S TOBOM 18 21 0 21 TABU - PRVI ZADNJI 19 20 0 20 FILATOV & KARAS - TELL IT TO MY HEART 20 20 0 20 TWENTY ONE PILOTS - HEATHENS 21 19 0 19 OMAR NABER - POSEBEN DAN 22 19 0 19 X AMBASSADORS - RENEGADES 23 19 0 19 SHAKIRA - TRY EVERYTHING 24 18 0 18 NIET - OPROSTI MI 25 18 0 18 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 26 18 0 18 MANCA ŠPIK & ISAAC PALMA - OBA 27 17 0 17 PANDA - SANJE 28 17 0 17 KINGS OF LEON - WASTE A MOMENT 29 17 0 17 LEONART - DANES ME NI 30 17 0 17 CLEAN BANDIT & SEAN PAUL & ANNE MARIE - ROCKBABY 31 17 0 17 HONNE - GOOD TOGETHER 32 16 0 16 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 33 16 0 16 LADY GAGA - PERFECT ILLUSION 34 16 0 16 MAGNIFICO - KUKU LELE 35 15 0 15 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE - CAN'T STOP THE FEELINGS 36 15 0 15 BON JOVI - REUNION 37 15 0 15 NEK - UNICI 38 15 0 15 STRUMBELLAS - SPIRIT 39 15 0 15 PARSON JAMES - SAD SONG 40 15 0 15 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - I FEEL IT COMING 41 15 0 15 AVIICI & CONRAD SWELL - TASTE THE FEELING 42 15 0 15 DAVID & ALEX & SAM - TA OBČUTEK 43 14 0 14 I.C.E. -

Fiera Internazionale Del Libro Di Torino

Fiera Internazionale del Libro 2007 XX edizione Torino - Lingotto Fiere, 10-14 maggio I CONFINI, TEMA CONDUTTORE DELLA FIERA 2007 Torino, 16 aprile 2007 - L’edizione 2007, con cui la Fiera del libro festeggerà i suoi vent’anni, avrà per tema conduttore i confini. Un motivo che consentirà di affrontare alcuni tra i problemi più scottanti della nostra epoca. Il confine è infatti ciò che segna un limite, e dunque separa, ma insieme unisce, mette in relazione. E’ il limite che bisogna darsi per cercare di superarlo. E’ la porta del confronto con noi stessi e con gli altri. E’ una linea mobile che esige una continua ridefinizione. Un concetto che la Fiera intende appunto declinare nella sua accezione di apertura e di scambio. Il confine mette in gioco un’idea di polarità, di opposizioni chiamate a misurarsi, a rispettarsi e a dialogare. E allo stesso tempo ci rimanda l’immagine complessa, paradossale e contraddittoria del mondo d’oggi. Primo paradosso: un mondo sempre più virtualizzato e globale sembrerebbe avere attenuato o addirittura abolito il concetto di separatezza, sostituito da quello di un gigantesco mercato, che consuma ovunque i medesimi prodotti. Eppure i confini cancellati dai mercati ritornano drammaticamente sia nella crescente divaricazione tra Paesi ricchi e Paesi poveri, sia nell’affermazione di esasperate identità locali, opposte le une e altre, che si risolvono in tensioni, conflitti, guerre di tutti contro tutti. Le divisioni etniche e religiose, lungi dal conciliarsi in un dialogo possibile, scatenano opposizioni sempre più radicali e devastanti, che si affidano al braccio armato dei terrorismi. La miscela di cosmopolitismo, globalizzazione e fanatismi locali produce nuovi recinti e innalza nuovi muri. -

Retabloid Gennaio 2020

«Amo l’astrazione della sofferenza.» Percival Everett gennaio 2020 retabloid_gen20_7feb.indd 1 07/02/2020 14:57:43 Valentina Maini è nata nel 1987 a Bologna. Ha conseguito un dottorato in Letterature comparate tra Bologna e Parigi. Con la rac- colta di poesie Casa rotta, (2016) ha vinto il premio letterario Anna Osti. Traduce dal- l’inglese e dal francese. Il 20 febbraio 2020 esce La mischia per Bollati Boringhieri. Marina Viola è nata a Milano ma vive a Boston con il marito Dan, i tre figli e due cani. Ha pubblicato Mio padre è stato an- che Beppe Viola (Feltrinelli, 2013) e Storia del mio bambino perfetto (Rizzoli, 2015). È appena uscito Loro fanno l’amore (e io m’in- cazzo) per Sonzogno. retabloid – la rassegna culturale di Oblique gennaio 2020 Il copyright dei racconti, degli articoli e delle foto ap- partiene agli autori. Cura e impaginazione di Oblique Studio. Leggiamo le vostre proposte: racconti, reportage, poesie, pièce. Guardiamo le vostre proposte: fotografie, disegni, illustrazioni. Regolamento su oblique.it. Segnalateci gli articoli meritevoli che ci sono sfuggiti. [email protected] retabloid_gen20_7feb.indd 2 07/02/2020 14:57:43 I racconti • Valentina Maini, Un giorno dopo l’altro 5 • Marina Viola, Ecco che arriva il tipo dell’Alabama 10 Le interviste • Giovanni Nucci ∙ Italosvevo Edizioni 13 • Roberta De Marchis ∙ Italosvevo Edizioni 20 Gli articoli del mese # Leggere e ritrovare la strada di casa Luisa Carrada, blog.mestierediscrivere.com, 2 gennaio 2020 27 # L’ultima biblioteca dell’umanità Alberto Manguel, «Robinson», 4 gennaio 2020 30 # Non lo cercò solo Leopardi. -

Trieste 2020, the European City of Science Published on Iitaly.Org (

Trieste 2020, the European City of Science Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Trieste 2020, the European City of Science Roberta Cutillo (January 10, 2020) One of the most important scientific hubs in Europe, the Northeastern Italian city of Trieste is ready to kick off its year as the European City of Science, during which it will host the EuroScience Open Forum, the largest biennial general science meeting in Europe, as well as the The Science in the City Festival, which will be open to the public. Trieste begins its year as the 2020 European City of Science. The Northeastern Italian city was chosen by the European Science Forum (Esof) over fellow finalists Leiden and the Hague, which had partenered up to represent the Netherlands. The nomination is a recognition of the value of the area’s academic and research network comprised of the SISSA (International School for Advanced Studies), the Elettra Sincrotrone research center, the National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics, and the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology. Page 1 of 2 Trieste 2020, the European City of Science Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) In addition to seminaries, workshops, panels, and other encounters dedicated to discussing and presenting the latest advancements in the fields of technology, innovation, science, and politics, which will take place from July 5-9 during the EuroScience Open Forum, the city will also host a Science Festival from June 27 to July 11. The event will be open to the public and feature notable guests such as Swiss astronomer Didier Queloz, who was awarded the 2019 Nobel Physics Prize along with James Peebles and Michel Mayor, and Scottish biochemist Iain Mattaj. -

Robert Walser, Paul Scheerbart, and Joseph Roth Vi

Telling Technology Contesting Narratives of Progress in Modernist Literature: Robert Walser, Paul Scheerbart, and Joseph Roth Vincent Hessling Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Vincent Hessling All rights reserved ABSTRACT Telling Technology Contesting Narratives of Progress in Modernist Literature: Robert Walser, Paul Scheerbart, and Joseph Roth Vincent Hessling Telling technology explores how modernist literature makes sense of technological change by means of narration. The dissertation consists of three case studies focusing on narrative texts by Robert Walser, Paul Scheerbart, and Joseph Roth. These authors write at a time when a crisis of ‘progress,’ understood as a basic concept of history, coincides with a crisis of narra- tion in the form of anthropocentric, action-based storytelling. Through close readings of their technographic writing, the case studies investigate how the three authors develop alter- native forms of narration so as to tackle the questions posed by the sweeping technological change in their day. Along with a deeper understanding of the individual literary texts, the dissertation establishes a theoretical framework to discuss questions of modern technology and agency through the lens of narrative theory. Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii INTRODUCTION: Toward a Narratology of Technological Change 1 CHAPTER I: Robert Walser’s Der Gehülfe: A Zero-Grade Narrative of Progress 26 1. The Employee as a Modern Topos 26 2. The Master and the Servant: A Farce on Progress 41 3. Irony of ‘Kaleidoscopic Focalization’ 50 4. The Inventions and their Distribution 55 5. -

Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Capano, Fabio, "Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5312. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5312 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianità," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Modern Europe Joshua Arthurs, Ph.D., Co-Chair Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Co-Chair Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996). -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

William Weaver Papers, 1977-1984

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4779q44t No online items Finding Aid for the William Weaver Papers, 1977-1984 Processed by Lilace Hatayama; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the William 2094 1 Weaver Papers, 1977-1984 Descriptive Summary Title: William Weaver Papers Date (inclusive): 1977-1984 Collection number: 2094 Creator: Weaver, William, 1923- Extent: 2 boxes (1 linear ft.) Abstract: William Weaver (b.1923) was a free-lance writer, translator, music critic, associate editor of Collier's magazine, Italian correspondent for the Financial times (London), music and opera critic in Italy for the International herald tribune, and record critic for Panorama. The collection consists of Weaver's translations from Italian to English, including typescript manuscripts, photocopied manuscripts, galley and page proofs. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections. -

Development of a Literary Dispositif

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 4-5-2018 Development of a Literary Dispositif: Convening Diasporan, Blues, and Cosmopolitan Lines of Inquiry to Reveal the Cultural Dialogue Among Giuseppe Ungaretti, Langston Hughes, and Antonio D’Alfonso Anna Ciamparella Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, Italian Language and Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Ciamparella, Anna, "Development of a Literary Dispositif: Convening Diasporan, Blues, and Cosmopolitan Lines of Inquiry to Reveal the Cultural Dialogue Among Giuseppe Ungaretti, Langston Hughes, and Antonio D’Alfonso" (2018). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4563. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4563 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. DEVELOPMENT OF A LITERARY DISPOSITIF: CONVENING DIASPORAN, BLUES, AND COSMOPOLITAN LINES OF INQUIRY TO REVEAL THE CULTURAL DIALOGUE AMONG GIUSEPPE UNGARETTI, LANGSTON HUGHES, AND ANTONIO D’ALFONSO A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Interdisciplinary Program in Comparative Literature by Anna Ciamparella M.A. -

Milan Celtic in Origin, Milan Was Acquired by Rome in 197 B.C. an Important Center During the Roman Era (Mediolânum Or Mediola

1 Milan Celtic in origin, Milan was acquired by Rome in 197 B.C. An important center during the Roman era (Mediolânum or Mediolanium), and after having declined as a medieval village, it began to prosper as an archiepiscopal and consular town between the tenth and eleventh centuries. It led the struggle of the Italian cities against the Emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa) at Legnano (1176), securing Italian independence in the Peace of Constance (1183), but the commune was undermined by social unrest. During the thirteenth century, the Visconti and Della Torre families fought to impose their lordship or signoria. The Viscontis prevailed, and under their dominion Milan then became the Renaissance ducal power that served as a concrete reference for the fairy-like atmosphere of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Meanwhile, Milan’s archbishopric was influential, and Carlo Borromeo (1538-1584) became a leading figure during the counter-Reformation. Having passed through the rule of the Sforzas (Francesco Sforza ruled until the city was captured by Louis XII of France in 1498) and the domination of the Hapsburgs, which ended in 1713 with the war of the Spanish Succession, Milan saw the establishment of Austrian rule. The enlightened rule of both Hapsburg emperors (Maria Theresa and Joseph II) encouraged the flowering of enlightenment culture, which Lombard reformers such as the Verri brothers, Cesare Beccaria, and the entire group of intellectuals active around the journal Il caffè bequeathed to Milan during the Jacobin and romantic periods. In fact, the city which fascinated Stendhal when he visited it in 1800 as a second lieutenant in the Napoleonic army became, between the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century, a reference point in the cultural and social field. -

The Funerals of the Habsburg Emperors in the Eighteenth Century

The Funerals of the Habsburg Emperors In the Eighteenth Century MARK HENGERER 1. Introduction The dassic interpretation of the eighteenth century as aperiod of transition-from sacred kingship to secular state, from a divine-right monarchy to enlightened absolutism, from religion to reason-neglects, so the editor of this volume suggests, aspects of the continuing impact of religion on European royal culture during this period, and ignores the fact that secularization does not necessarily mean desacralization. If we take this point of view, the complex relationship between monarchy and religion, such as appears in funerals, needs to be revisited. We still lack a comparative and detailed study of Habsburg funerals throughout the entire eighteenth century. Although the funerals of the emperors in general have been the subject of a great deal of research, most historians have concentrated either on funerals of individual ruIers before 1700, or on shorter periods within the eighteenth century.l Consequently, the general view I owe debts of gratitude to MeJana Heinss Marte! and Derek Beales for their romments on an earlier version ofthis essay, and to ThomasJust fi'om the Haus-, Hof und Staatsarchiv, Vienna, for unbureaucratic access to the relevant source material. I Most attention has heen paid to Emperor Maximilian 1. Cf., among olhers, Peter Schmid, 'Sterben-Tod-Leichenbegängnis Kaiser Maximilians 1.', in Lothar Kolmer (ed.), Der Tod des A1iichtigen: Kult und Kultur des Sterbe1l5 spätmittelalterlicher Herrscher (Paderborn, 1997), 185-215; Elisaheth Scheicher, 'Kaiser Maximilian plant sein Denkmal', Jahrbuch des kunsthislmischen Museums Wien, I (1999), 81-117; Gabriele Voss, 'Der Tod des Herrschers: Sterbe- und Beerdigungsbrauchtum beim Übertritt vom Mittelalter in die frühe Neuzeit am Beispiel der Kaiser Friedrich IH., Maximilian L und Kar! V: (unpuhlished Diploma thesis, University ofVienna, 1989).