Vol26-No2-92.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Lineage-Patriarchen-Soto-Zen.Pdf

De lineage van de Patriarchen Sōtō Zen 1. Bibashi Butsu Daioshō 2. Shiki Butsu Daioshō 3. Bishafu Butsu Daioshō 4. Kuruson Butsu Daioshō 5. Kunagommuni Butsu Daioshō 6. Kashō Butsu Daioshō 7. SHAKAMUNI BUTSU DAIOSHO –> (Shakyamuni, Gautama, Siddhata, ca. 563 v.C. - 483 v.C.) 8. Makakashō Daioshō 9. Ananda Daioshō 10. Shōnawashu Daioshō 11. Ubakikuta Daioshō 12. Daitaka Daioshō 13. Mishaka Daioshō 14. Bashumitsu Daioshō 15. Butsudanandai Daioshō 16. Fudamitta Daioshō 17. Barishiba Daioshō 18. Funayasha Daioshō 19. Anabotei Daioshō 20. Kabimora Daioshō 21. Nagyaharajunya Daiosho (Nagarjuna) 22. Kanadaiba Daioshō 23. Ragorata Daioshō 24. Sōgyanandai Daioshō 25. Kayashata Daioshō 26. Kumorata Daioshō 27. Shayata Daioshō 28. Bashubanzu Daioshō 29. Manura Daioshō 30. Kakurokuna Daioshō 31. Shishibodai Daioshō 32. Bashashita Daioshō 33. Funyomitta Daioshō 34. Hannyatara Daioshō 35. BODAIDARUMA DAIOSHO (Bodhidharma, P'u-t'i-ta-mo, Daruma, Bodaidaruma, ca. 470-543) 36. Taisō Eka Daioshō (Hiu-k'o, 487-593) 37. Kanchi Sōsan Daioshō (Seng-ts'an, gest. 606 ?) 38. Daii Dōshin Daioshō (Tao-hsin, 580-651) 39. Daiman Kōnin Daioshō (Gunin, Hung-jen, 601-674) 40. Daikan Enō Daioshō (Hui-neng, 638-713) 41. Seigen Gyōshi Daioshō (Ch'ing-yuan Hsing-ssu, 660-740) 42. Sekitō Kisen Daioshō (Shih-t'ou Hsi-ch'ein, 700-790) 43. Yakusan Igen Daioshō (Yüeh-shan Wei-yen, ca. 745-828) 44. Ungan Donjō Daioshō (Yün-yen T'an-shing, 780-841) 45. Tozan Ryokai Daioshō (Tung-shan Liang-chieh, 807-869) 46. Ungo Doyo Daioshō (Yün-chü Tao-ying, gest. 902) 47. Dōan Dōhi Daioshō 48. Dōan Kanshi Daioshō 49. Ryōzan Enkan Daioshō (Liang-shan Yüan-kuan) 50. -

Wind Bell He Spent Time with Suzuki-Roshi Gathering Material for a Wind Bell About His Life and Practice in Japan As a Boy and a Man Before Coming Co America

4, .. ,_ PURLICATl0"4 Of· Zf 'Cl.N f ER VO LU~IE XI. 1972 Ocean Wind Zendo Gate, gate, paragate, parasamgate! Bodhi! Svaha! Go,ne, gone, gone beyond, beyond beyond! Bodhi! Svaha! ' 3 Our teacher is gone. Nothing can express our feeling for Suzuki-roshi except the complete continuation of his teaching. We continue his existence. in the light of his mind and spirit as our own and Buddha's mind and spirit. He made clear that the Other Shore is here. This time includes past, present and future, our existence, his existence, Buddha's time. It was and is true for Suzuki-roshi. We are him and he is us. He expressed this in teaching us by going away. Gone, gone co the Other Shore! Beyond the Other Shore! Bodhil Svaha! Cyate gyate hara gyate liara so gyate! Boji! Sowaka! 4 JN A LEITER that went out to some of you from Yvonne Rand, President of Zen Center, she wrote: "Suzuki-roshi died early in the morning, Saturday, December 4, 1971 just after the sounding of the opening bell of the five-day sesshin commemorating Buddha's Enlightenment. He left us very gently and calmly. And he left Zen Center very carefully, teaching us in everything he did. There is almost no sense of his being gone, for he continues to live clearly in the practice and community that were his life work. His last appearance in public was on November 21 at the ceremony to install Richard Baker-roshi as his successor, according to his long-standing plan. -

Opening the Hand of Thought Goes Directly to the Heart of Zen Practice

To all who are practicing the buddhadharma Sitting itself is the practice of the Buddha. Sitting itself is nondoing. It is nothing but the true form of the self. Apart from sitting, there is nothing to seek as the buddhadharma. Eihei Dōgen Zenji Shōbōgenzō—Zuimonki (“Sayings of Eihei Dōgen Zenji”) Contents EPIGRAPH PREFACES The Story of This Book and Its Author by Jisho Warner Teacher and Disciple by Shohaku Okumura On the Nature of Self by Daitsu Tom Wright The Theme of My Life by Kōshō Uchiyama 1. PRACTICE AND PERSIMMONS How Does a Persimmon Become Sweet? The Significance of Buddhist Practice The Four Seals Practice is for Life 2. THE MEANING OF ZAZEN Depending on Others Is Unstable The Self That Lives the Whole Truth Everything Is Just As It Is Living Out the Reality of Life 3. THE REALITY OF ZAZEN How to Do Zazen Letting Go of Thoughts Waking Up to Life 4. THE WORLD OF INTENSIVE PRACTICE Sesshins Without Toys Before Time and “I” Effort The Scenery of Life 5. ZAZEN AND THE TRUE SELF Universal Self The Activity of the Reality of Life 6. THE WORLD OF SELF UNFOLDS The Dissatisfactions of Modern Life Self Settling on Itself Interdependence and the Middle Way Delusion and Zazen 7. LIVING WIDE AWAKE Zazen as Religion Vow and Repentance The Bodhisattva Vow Magnanimous Mind The Direction of the Universal 8. THE WAYSEEKER Seven Points of Practice 1. Study and Practice the Buddhadharma 2. Zazen Is Our Truest and Most Venerable Teacher 3. Zazen Must Work Concretely in Our Daily Lives 4. -

Research Article

Research Article Journal of Global Buddhism 2 (2001): 139 - 161 Zen in Europe: A Survey of the Territory By Alione Koné Doctoral Candidate Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Science Sociales (Paris) [email protected] © Copyright Notes Digitial copies of this work may be made and distributed provided no charge is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format with the exception of a single copy for private study requires the written permission of the author. All enquries to [email protected] http://jgb.la.psu.edu Journal of Global Buddhism 139 ISSN 1527-6457 Zen in Europe: A Survey of the Territory By Alioune Koné Doctoral Candidate Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Paris) [email protected] Zen has been one of the most attractive Buddhist traditions among Westerners in the twentieth century. Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese teachers have created European organizations in the past forty years, and some of their students have started teaching. While their American counterparts are well documented in the growing literature on the making of a Western Buddhism, the European groups are less known.(1) This paper aims at highlighting patterns of changes and adaptations of Zen Buddhism in Europe. It proposes an overview of European Zen organizations and argues that an institutional approach can highlight important aspects of the transplantation of Zen Buddhism into a new culture. A serious shortcoming of such an endeavor was pointed out in a 1993 conference held in Stockholm. A group -

Opening the Hand of Thought : Approach To

TRANSLATED BY SHOHAKl AND TOM WRIGHT ARKANA OPENING THE HAND OF THOUGHT Kosho Uchiyama Roshi was born in Tokyo in 1911. He received a master's degree in Western philosophy at Waseda University in 1937 and became a Zen priest three years later under Kodo Sawaki Roshi. Upon Sawaki Roshi's death in 1965, he assumed the abbotship of Antaiji, a temple and monastery then located near Kyoto. Uchiyama Roshi developed the practice at Anataiji, including monthly five-day sesshins, and often traveled throughout Japan, lec- turing and leading sesshins. He retired from Antaiji in 1975 and now lives with his wife at N6ke-in, a small temple outside Kyoto. He has written over twenty texts on Zen, including translations of Dogen Zenji into modern Japanese with commentaries, one of which is available in English (Refining Your Life, Tokyo: Weatherhill, 1983). Uchiyama Roshi is also well known in the world of origami, of which he is a master; he has published several books on origami. Shohaku Okumura was born in Osaka, Japan, in 1948. He studied Zen Buddhism at Komazawa University in Tokyo and was ordained as a priest by Uchiyama Roshi in 1970, practicing under him at An- taiji. From 1975 to 1982 he practiced at the Pioneer Valley Zendo in Massachusetts. After he returned to Japan, he began translating Dogen Zenji's and Uchiyama Roshi's writings into English with Tom Wright and other American practitioners. From 1984 to 1992 Rev. Okumura led practice at Shorinji, near Kyoto, as a teacher of the Kyoto Soto Zen Center, working mainly with Westerners. -

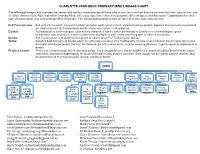

JOKO CHARLOTTE JOKO BECK ORDINARY MIND LINEAGE CHART Ezra Bayda: [email protected] Gary Nafstad (No Contact) Larry Chris

CHARLOTTE JOKO BECK ORDINARY MIND LINEAGE CHART The following lineage chart provides the names and contact information for all those who at one time received dharma transmission from Joko or from one of Joko's dharma heirs. Note that within Ordinary Mind, different people have chosen to designate different types of transmission. Explanations for each type of transmission may vary amongst different people. The following description is only an attempt to give some idea of each. Full Transmission: Full authority to teach, transmit to others and give Jukai. Given to both ordained and lay people. Appears that everyone transmitted by Joko received Full Transmission whether they were or were not ordained. Denkai: Authorization to teach and give Jukai but not transmit. It can be either preliminary to Denbo or a terminal degree, given to someone who teaches in a context other than having their own zendo and being able to name a successor. Denbo: Full Transmission with authority to transmit to others (as in Full Transmission above.) Shiho: Includes both Denkai and Denbo which are often done at same time.Traditionally, Denkai means transmit the precepts (kai means precepts) and denbo means transmit the Dharma (bo is the same as ho in shiho meaning dharma). It can be given to ordained or lay people. Practice Leader: This is not a transmission and is not listed below. It is a recognition of a senior student as a leader who gives dharma talks, zazen instruction, and takes responsibility for much of the day to day practice activities. S/he usually works closely with the teacher. -

The Practice of Compassion

Soto Zen Buddhism in Australia JIKI060 June Edition, Volume 14(4) 2015 THE PRACTICE OF COMPASSION The Abbots’ Cemetery. Toshoji Temple, Okayakama Prefecture, JAPAN. Photograph: Rev Seishin Nicholls IN THIS ISSUE In this issue Ekai Osho’s Dharma Talk is about con- flects on what he learnt being Myoju Co-ordinator; necting practice and study to compassion and wis- Nicky Coles takes a night bicycle ride; Diana Liu asks dom; Seishin Nicholls tells an inspiring story of com- some profound questions after her first retreat; Karen passionate action; Naomi Richards considers what Threlfall discovers the joy of quinces; Ronan McShane we see and what we choose not to; Azhar Abidi re- and Ariella Schreiner have fun at the Sangha Picnic. MYOJU IS A PUBLICATION OF JIKISHOAN ZEN BUDDHIST COMMUNITY INC 1 Editorial Myoju Welcome to this Winter edition of Myoju with the theme Editor: Ekai Korematsu ‘The Practice of Compassion’. The days are short, the nights Editorial Committee: Hannah Forsyth, are long and the air is cold; a perfect time for going inside. Christine Maingard, Katherine Yeo, Azhar Abidi Myoju Co-ordinator: Robin Laurie Ekai Osho’s Dharma talk emphasises the need for both Production: Vincent Vuu study and training to cultivate compassion in action in the Production Assistance: James Watt world. He says, ‘Settling down to original nature is a good Transcription Co-ordinator: Azhar Abidi thing. You still have to stand up and go outside and speak Website Manager: Lee-Anne Armitage to others.’ IBS Teaching Schedule: Hannah Forsyth / Shona Innes Jikishoan Calendar of Events: Katherine Yeo Seishin Nicholl’s and Naomi Richard’s articles both com- Contributors: Ekai Korematsu Osho, Seishin Nicholls, ment on how compassion can sometimes be expressed Azhar Abidi, Nicky Coles, Diana Liu, Ronan McShane, in ways that are unexpected or apparently strange. -

Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan

Soto Zen in Medieval Japan Kuroda Institute Studies in East Asian Buddhism Studies in Ch ’an and Hua-yen Robert M. Gimello and Peter N. Gregory Dogen Studies William R. LaFleur The Northern School and the Formation of Early Ch ’an Buddhism John R. McRae Traditions of Meditation in Chinese Buddhism Peter N. Gregory Sudden and Gradual: Approaches to Enlightenment in Chinese Thought Peter N. Gregory Buddhist Hermeneutics Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Paths to Liberation: The Marga and Its Transformations in Buddhist Thought Robert E. Buswell, Jr., and Robert M. Gimello Studies in East Asian Buddhism $ Soto Zen in Medieval Japan William M. Bodiford A Kuroda Institute Book University of Hawaii Press • Honolulu © 1993 Kuroda Institute All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 93 94 95 96 97 98 5 4 3 2 1 The Kuroda Institute for the Study of Buddhism and Human Values is a nonprofit, educational corporation, founded in 1976. One of its primary objectives is to promote scholarship on the historical, philosophical, and cultural ramifications of Buddhism. In association with the University of Hawaii Press, the Institute also publishes Classics in East Asian Buddhism, a series devoted to the translation of significant texts in the East Asian Buddhist tradition. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bodiford, William M. 1955- Sotd Zen in medieval Japan / William M. Bodiford. p. cm.—(Studies in East Asian Buddhism ; 8) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8248-1482-7 l.Sotoshu—History. I. Title. II. Series. BQ9412.6.B63 1993 294.3’927—dc20 92-37843 CIP University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources Designed by Kenneth Miyamoto For B. -

PDF Download

Who? What? Where? When? Why? Uncovering the Mysteries of Monastery Objects by Ven. Shikai Zuiko o-sensei Zenga by Ven. Anzan Hoshin roshi Photographs by Ven. Shikai Zuiko o-sensei and Nathan Fushin Comeau Article 1: Guan Yin Rupa As you enter the front door of the Monastery you may have noticed a white porcelain figure nearly two feet tall standing on the shelf to the left. Who is she? Guan Yin, Gwaneum, Kanzeon, are some of the names she holds from Chinese, Korean, and Japanese roots. The object is called a "rupa" in Sanskrit, which means "form" and in this case a statue that has the form of a representation of a quality which humans hold dear: compassion. I bought this 20th century rupa shortly after we established a small temple, Zazen-ji, on Somerset West. This particular representation bears a definite resemblance to Ming dynasty presentations of "One Who Hears the Cries of the World". Guan Yin, Gwaneum, Kanzeon seems to have sprung from the Indian representation of the qualities of compassion and warmth portrayed under another name; Avalokitesvara. The name means "looking down on and hearing the sounds of lamentation". Some say that Guan Yin is the female version of Avalokitesvara. Some say that Guan Yin or, in Japan, Kannon or Kanzeon, and Avalokitesvara are the same and the differences in appearance are the visibles expression of different influences from different cultures and different Buddhist schools, and perhaps even the influence of Christianity's madonna. Extensive background information is available in books and on the web for those interested students. -

What Is Buddha Nature?

Vol. 7 No. 2 March/April 2006 2548 BE Water Wheel Being one with all Buddhas, I turn the water wheel of compassion. —Gate of Sweet Nectar What is Buddha Nature? By Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao to us humans. A pine tree, a chair, a dog—these have no Our study of the fundamental aspects of Zen practice problem being pine begins with an exploration of buddha-nature. In the Sho- tree, chair, and dog bogenzo fascicle “Bussho,” Dogen Zenji writes: respectively. Only human beings are All sentient beings without exception have the Buddha under the false illu- nature. The Tathagata abides forever without change. sion of a permanent, fixed “I” or ego, or small self. We are so deeply attached Let us examine the first line, which is often expounded to “me-myself” that it seems impossible to even consider in the Mahayana sutras. This statement points directly to that this is an illusion to be seen through as universal the essential nature of this very life that we are now living. whole-being. It is our task to understand this nature, to experience it directly for ourselves, and to live it in our daily lives. Have the. Although this translation uses the words “have the,” Dogen Zenji says that it is more to the point All sentient beings. We can distinguish between human to say “are.” All beings are buddha-nature. You, the pine, the beings, sentient beings, and whole-being. The word rocks, the dog, already are complete, whole, perfect as is. “sentient” means “responsive to sensations,” so it includes Buddha-nature is not something that you have, or can humans, plants, and animals. -

Prajñatara: Bodhidharma's Master

Summer 2008 Volume 16, Number 2 Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women TABLE OF CONTENTS Women Acquiring the Essence Buddhist Women Ancestors: Hymn to the Perfection of Wisdom Female Founders of Tibetan Buddhist Practices Invocation to the Great Wise Women The Wonderful Benefits of a H. H. the 14th Dalai Lama and Speakers at the First International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha Female Lineage Invocation WOMEN ACQUIRING THE ESSENCE An Ordinary and Sincere Amitbha Reciter: Ms. Jin-Mei Roshi Wendy Egyoku Nakao Chen-Lai On July 10, 1998, I invited the women of our Sangha to gather to explore the practice and lineage of women. Prajñatara: Bodhidharma’s Here are a few thoughts that helped get us started. Master Several years ago while I was visiting ZCLA [Zen Center of Los Angeles], Nyogen Sensei asked In Memory of Bhiksuni Tian Yi (1924-1980) of Taiwan me to give a talk about my experiences as a woman in practice. I had never talked about this before. During the talk, a young woman in the zendo began to cry. Every now and then I would glance her One Worldwide Nettwork: way and wonder what was happening: Had she lost a child? Ended a relationship? She cried and A Report cried. I wondered what was triggering these unstoppable tears? The following day Nyogen Sensei mentioned to me that she was still crying, and he had gently Newsline asked her if she could tell him why. “It just had not occurred to me,” she said, “that a woman could be a Buddha.” A few years later when I met her again, the emotions of that moment suddenly surfaced.