Download Article [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalisation and the Nigerian State

GLOBALISATION AND THE NIGERIAN STATE BY Ariyo Andrew TOBI B.Sc. Pol.Science (Ogun), M.Sc. Pol.Science (Ibadan) Matric No: 73067 A Thesis in the Department of Political Science, submitted to the Faculty of the Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN June , 2013. i BIBLIOGRAPHY A: BOOKS Abegunrin, O.2006. Nigeria‟s foreign policy under Obasanjo administration, 1999- 2005 Nigeria in global politics: twentieth century and beyond. O.Abegunrin, and O.komolafe, Eds. New York : Nova Science Publisher, Inc. Adesina, O.2006.Development and the challenge of poverty:. Africa & development: challenges in the new millennium. the NEPAD debate. J.O Adesina Y.Graham & Olukoshi. Eds.Dakar CODESRIA in association with London:Zed Books and Pretoria:UNISA Press, Ake, C. 2000.The feasibility of democracy in Africa. Dakar: CODESRIA., ________ 1996.The political question. Governance and Development in Nigeria. O. Oyediran. Ed. Ibadan: Oyediran Consult International. __________.1996. The marginalisation of Africa :notes on a productive confusion. Lagos: Malthouse Press Ltd. __________1985. The Nigerian state: antimonies of a periphery formation. Political economy of Nigeria C Ake, Ed. .London and Lagos: Longman. Akinsanya, A. A.2005.Inevitability of instability in Nigeria. Readings in Nigerian Government and Politics .Ijebu-Ode :Gratia Associates. A.A. Akinsanya and J. A. A. Ayooade Eds. Ijebu-Ode: Gratia Associates International. ________.2002.Four years of presidential democracy in Nigeria. Nigerian Government and Politics 1979-1983. A.A Akinsanya and G.J Idang Eds.: .Calabar: WUSEN Publishers Akinterinwa,B.2004. Ed. Nigeria’s new foreign policy thrust. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Original Research Article

1 Original Research Article 2 3 Effects of Different Types of Organic Fertilizers on Growth Performance of 4 Amaranthus caudatus (Samaru Local Variety) and Amaranthus cruentus 5 (NH84/452) 6 7 8 9 10 ABSTRACT 11 To evaluate the effect of different types of organic fertilizers on growth performance of Amaranthus 12 caudatus (Samaru local variety) and Amaranthus cruentus (NH84/452). A randomized complete block 13 design (RCBD) was used for the experiment. The field experiment was carried out in the nursery of a 14 homestead garden at No 20, Isaiah Balat Street, Sabo GRA, Kaduna State, Nigeria. The study consists of 15 seven treatments which includes control (no fertilizer), 5 tons/ha and 10 tons/ha poultry manure, 5 tons/ha 16 and 10 tons/ha sewage sludge, 35kg/ha and 70kg/ha NPK compound fertilizer and also with Amaranthus 17 caudatus (Samaru local variety) and Amaranthus cruentus (NH84/452) in factorial arrangement fitted into 18 a randomized complete block design (RCBD) and replicated three times. Growth performance data were 19 collected on plant height, number of leaves, leaf length, leaf width, leaf area and leaf area index from 2 20 weeks after transplanting (WAT) to 6 weeks after transplanting (WAT). The plant height and number of 21 leaves of the two varieties were found in the range of 18.30-135.67cm and 13.33-78.33cm respectively. 22 Leaf area and leaf area index of the two varieties had values in the range of 41.71-258.29cm 2 and 1.76- 23 41.72 respectively. At 6WAT, 10tons/ha poultry manure recorded the highest value for all the growth 24 parameters for both varieties except for leaf length, leaf width and leaf area of Amaranthus caudatus 25 (Samaru local variety) , where 10 tons/ha sewage sludge and 70kg/ha NPK compound fertilizer were 26 highest. -

QUALIFIED APPLICANTS for TSB EXAMS in ZIIT, ZARIA ZARIA EXAM CENTRE ZIIT, No 19,Wusasa - Kofan Doka, Road, Behind Eid Ground, Zaria

KADUNA STATE TEACHERS SERVICE BOARD QUALIFIED APPLICANTS FOR TSB EXAMS IN ZIIT, ZARIA ZARIA EXAM CENTRE ZIIT, No 19,Wusasa - Kofan Doka, Road, Behind Eid Ground, Zaria S/N Application No Firstname Surname Other Names Specialization Exam Centre Exam Date Exam Time 9:00am to 1 KSTSB/R/20/000758 ABBA ABDULLAHI TANIMU Chemistry Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 2 KSTSB/R/20/000215 Abba Abubakar Basic Technology Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 3 KSTSB/R/20/001582 ABBAS HAMISU Social Studies Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 4 KSTSB/R/20/000784 AbdulAzeez Garba Samaru Agricultural Science Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 5 KSTSB/R/20/046598 Abdulazeez Hussaini Government Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 6 KSTSB/R/20/021407 Abdulfatah Salihu Marketing Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 7 KSTSB/R/20/000090 AbdulGaniyu Nurudeen Government Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am Islamic Religion 9:00am to 8 KSTSB/R/20/002042 Abdulhalim Aliyu Alhassan knowledge Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 9 KSTSB/R/20/001002 Abdulhameed Jimoh Civic Education Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 10 KSTSB/R/20/001656 Abdulkabir Zubairu English Language Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am Islamic Religion 9:00am to 11 KSTSB/R/20/000066 Abdulkadir Akanni Aduagba knowledge Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 12 KSTSB/R/20/026735 Abdulkadir Abdulkadir murtala Geography Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 13 KSTSB/R/20/014426 ABDULKADIR MOHAMMED Economics Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 14 KSTSB/R/20/000826 Abdullahi Ahmad Civic Education Zaria 27-Jan-21 9:30am Information Communication 9:00am to 15 KSTSB/R/20/000933 -

Secretariat Distr.: Limited

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.615 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 6 October 2006 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SIXTY-FIRST SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan.........................................................................5 Cyprus.............................................................................. 32 Albania ...............................................................................5 Czech Republic ................................................................ 33 Algeria ...............................................................................6 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea .......................... 34 Andorra...............................................................................7 Denmark........................................................................... 35 Angola ................................................................................7 Djibouti ............................................................................ 36 Antigua and Barbuda ..........................................................8 Dominica.......................................................................... 36 Argentina............................................................................8 Dominican Republic......................................................... 37 Armenia..............................................................................9 -

The Solar System Has Been Designed to Provide 12 and 24 V DC

Chapter 11: Case Studies 311 The solar system has been designed to provide 12 and 24 V DC output in order to match the input voltage of all low power servers and workstations for NOC infrastructure and training classrooms. The solar panels used are Suntech STP080S-12/Bb-1 with the following specifications: • Open-circuit Voltage (VOC): 21.6 V • Optimum operating voltage (VMP): 17.2 V • Short-circuit current (ISC): 5 A • Optimum operating current (IMP): 4.65 A • Maximum power at STC (PMAX): 80 W (Peak) The minimum 6 KWh/day that feeds the NOC is used to power the following equipment: Device Hours/Day Units Power (W) Wh Access points 24 3 15 1080 Low power servers 24 4 10 960 LCD screens 2 4 20 160 Laptops 10 2 75 1500 Lamps 8 4 15 480 VSAT modem 24 1 60 1440 Total 5620 The power consumption for servers and LCD screens is based on Inveneo's Low Power Computing Station, http://www.inveneo.org/?q=Computingstation. The total estimated power consumption of the NOC is 5.6 kWh/day which is less than the daily power generated from the solar panels in the worst month. 312 Chapter 11: Case Studies Figure 11.2: The NOC is built by locally made laterite brick stones, produced and laid by youths in Kafanchan. Network Operating Center (NOC) A new Network Operating Center was established to host the power backup sys- tem and server room facilities. The NOC was designed to provide a place safe from dust, with good cooling capabilities for the batteries and the inverters. -

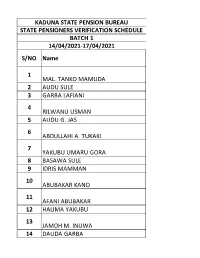

State Pensioners Verification Schedule 2021-Names

KADUNA STATE PENSION BUREAU STATE PENSIONERS VERIFICATION SCHEDULE BATCH 1 14/04/2021-17/04/2021 S/NO Name 1 MAL. TANKO MAMUDA 2 AUDU SULE 3 GARBA LAFIANI 4 RILWANU USMAN 5 AUDU G. JAS 6 ABDULLAHI A. TUKAKI 7 YAKUBU UMARU GORA 8 BASAWA SULE 9 IDRIS MAMMAN 10 ABUBAKAR KANO 11 AFANI ABUBAKAR 12 HALIMA YAKUBU 13 JAMOH M. INUWA 14 DAUDA GARBA 15 DAUDA M. UDAWA 16 TANKO MUSA 17 ABBAS USMAN 18 ADAMU CHORI 19 ADO SANI 20 BARAU ABUBAKAR JAFARU 21 BAWA A. TIKKU 22 BOBAI SHEMANG 23 DANAZUMI ABDU 24 DANJUMA A. MUSA 25 DANLADI ALI 26 DANZARIA LEMU 27 FATIMA YAKUBU 28 GANIYU A. ABDULRAHAMAN 29 GARBA ABBULLAHI 30 GARBA MAGAJI 31 GWAMMA TANKO 32 HAJARA BULUS 33 ISHAKU BORO 34 ISHAKU JOHN YOHANNA 35 LARABA IBRAHIM 36 MAL. USMAN ISHAKU 37 MARGRET MAMMAN 38 MOHAMMED ZUBAIRU 39 MUSA UMARU 40 RABO JAGABA 41 RABO TUKUR 42 SALE GOMA 43 SALISU DANLADI 44 SAMAILA MAIGARI 45 SILAS M. ISHAYA 46 SULE MUSA ZARIA 47 UTUNG BOBAI 48 YAHAYA AJAMU 49 YAKUBU S. RABIU 50 BAKO AUDU 51 SAMAILA MUSA 52 ISA IBRAHIM 53 ECCOS A. MBERE 54 PETER DOGO KAFARMA 55 ABDU YAKUBU 56 AKUT MAMMAN 57 GARBA MUSA 58 UMARU DANGARBA 59 EMMANUEL A. KANWAI 60 MARYAM MADAU 61 MUHAMMAD UMARU 62 MAL. ALIYU IBRAHIM 63 YANGA DANBAKI 64 MALAMA HAUWA IBRAHIM 65 DOGARA DOGO 66 GAIYA GIMBA 67 ABDU A. LAMBA 68 ZAKARI USMAN 69 MATHEW L MALLAM 70 HASSAN MAGAJI 71 DAUDA AUTA 72 YUSUF USMAN 73 EMMANUEL JAMES 74 MUSA MUHAMMAD 75 IBRAHIM ABUBAKAR BANKI 76 ABDULLAHI SHEHU 77 ALIYU WAKILI 78 DANLADI MUHAMMAD TOHU 79 MARCUS DANJUMA 80 LUKA ZONKWA 81 BADARAWA ADAMU 82 DANJUMA ISAH 83 LAWAL DOGO 84 GRACE THOT 85 LADI HAMZA 86 YAHAYA GARBA AHMADU 87 BABA A. -

Effects of Different Types of Organic Fertilizers on Growth Performance of Amaranthus Caudatus (Samaru Local Variety) and Amaranthus Cruentus (NH84/452)

Asian Journal of Advances in Agricultural Research 9(2): 1-12, 2019; Article no.AJAAR.47838 ISSN: 2456-8864 Effects of Different Types of Organic Fertilizers on Growth Performance of Amaranthus caudatus (Samaru Local Variety) and Amaranthus cruentus (NH84/452) J. C. Kahu1, C. C. Umeh1* and A. E. Achadu1,2 1Department of Biochemistry, Ahmadu Bello University, P.M.B 1013, Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria. 2Department of Biochemistry, Kogi State University, Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author JCK designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors CCU and AEA managed the analyses of the study. Author JCK managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJAAR/2019/v9i229994 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Adebayo Jonathan Adeyemo, Lecturer, Department of Crop, Soil and Pest Management, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. Reviewers: (1) Toungos, Mohammed Dahiru, Adamawa State University Mubi, Nigeria. (2) M. Abdullah Al Mamun, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Bangladesh. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/47838 Received 22 December 2018 Accepted 01 March 2019 Original Research Article Published 15 March 2019 ABSTRACT Aims: To evaluate the effect of different types of organic fertilizers on growth performance of Amaranthus caudatus (Samaru local variety) and Amaranthus cruentus (NH84/452). Study Design: A randomized complete block design (RCBD) was used for the experiment. Place and Duration of Study: The field experiment was carried out in the nursery of a homestead garden at No 20, Isaiah Balat Street, Sabo GRA, Kaduna State, Nigeria. -

Internet in Africa? >(A)Bort, (R)Etry, (F)Ail Authors and Contributors

>Internet in Africa? >(A)bort, (R)etry, (F)ail Authors and Contributors Main authors Louise Berthilson and Alberto Escudero Pascual, IT46 Contributors Dorothy Okello, Director of CWRC, Uganda Edwin Mugume, CWRC Project Officer [2006/07], Uganda Peterson Mwesiga, CWRC Project Officer [2007/09], Uganda Juma Okee, IT Officer CPAR Telecentre, Lira, Uganda Peter Nkurunungi, Network Manager, Kabale Network, Uganda John Dada, Director of Fantsuam Foundation, Nigeria Bidi Bala, Zittnet staff, Fantsuam Foundation, Nigeria Editor Martin Benjamin, Executive Director of Kamusi.org In Memoriam In memory of Adrian Tumwebaze Baryamujura, Kachwekano FM Community Multi-Media Centre, Kabale,Uganda, who passed away in July 2007. We had the pleasure of meeting Adrian through the Community Wireless Resource Centre. It was a true privilege to have the chance to get to know this enthusiastic and energetic young person, dedicated to his work and the Kabale community. With his wonderful personality, Adrian did not leave anyone untouched. His time on Earth was too short, but we are certain that he left many footprints in Kabale. It is our duty to make sure that all his work is remembered and continued within the community. Table of Contents 1. About this book.................................................................................1 2. Information technologies in developing regions..................................3 3. What is a Community Wireless Network?.........................................4 3.1 What are the driving forces behind Community Wireless -

Nigeria on the Brink?

Testimony of Mr. Emmanuel Ogebe, Esq. On behalf of Peaceful Polls Project Nigeria 2015 Nigeria on the Brink? Before the Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Rep. Christopher H. Smith, Chairman January, 27 2015 U.S. House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee Testimony of E. Ogebe, US Nigeria Law Group – Peaceful Polls Project 2015 1 1 Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member and Members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for the opportunity to testify before you today on an issue that is important to people concerned about terrorism and the state of human rights in our world today. I especially want to thank you, Chairman Smith, for your outstanding leadership on this issue; for traveling to Nigeria multiple times, at great personal risk, to further explore the situation; and for urging the Nigerian government to create a Boko Haram victim’s compensation fund. Thankfully, such a fund is being created. I. AT THE BRINK – AGAIN: TOWARDS NIGERIA’S VALENTINE’S DAY ELECTIONS Many years ago, a New York Times article wryly remarked that God was Nigerian. This facetious comment was predicated on the stunning comeback Nigeria made after years of brutal military dictatorship towards democracy without a violent upheaval. Today, some wonder if this holds true as Nigeria again faces yet another brink - maybe even the mother of all brinks. As Nigeria holds its 5th presidential elections in 16 years, since its return to civilian democracy, there are lots of centrifugal schisms at play. It is important to note the makeup of the past elections, in the delicate balancing act of region and religion that assuages simmering sensitivities in Nigeria: 1. -

Wireless Networking in the Developing World

Wireless Networking in the Developing World Second Edition A practical guide to planning and building low-cost telecommunications infrastructure Wireless Networking in the Developing World For more information about this project, visit us online at http://wndw.net/ First edition, January 2006 Second edition, December 2007 Many designations used by manufacturers and vendors to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the authors were aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in all caps or initial caps. All other trademarks are property of their respective owners. The authors and publisher have taken due care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information contained herein. © 2007 Hacker Friendly LLC, http://hackerfriendly.com/ This work is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license. For more details regarding your rights to use and redistribute this work, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ Contents Where to Begin 1 Purpose of this book........................................................................................................................... 2 Fitting wireless into your existing network.......................................................................................... 3 Wireless -

QUALIFIED APPLICANTS for TSB EXAMS in KAFANCHAN CAMPUS of KASU, KAFANCHAN EXAM CENTRE E-Library, KASU Kafanchan Campus, Kaduna State University, Kafanchan

KADUNA STATE TEACHERS SERVICE BOARD QUALIFIED APPLICANTS FOR TSB EXAMS IN KAFANCHAN CAMPUS OF KASU, KAFANCHAN EXAM CENTRE e-Library, KASU Kafanchan Campus, Kaduna State University, Kafanchan S/N Application No Firstname Surname Other Names Specialization Exam Centre Exam Date Exam Time 9:00am to 1 KSTSB/R/20/039770 Abdulmaliq Isah Biology Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 2 KSTSB/R/20/005066 Abednego Ayuba Economics Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 3 KSTSB/R/20/004202 ABEL YAKUBU HABILA Economics Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 4 KSTSB/R/20/000117 ABUBAKAR MUSA Biology Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 5 KSTSB/R/20/002867 Alex Yamai Delvan Geography Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 6 KSTSB/R/20/000897 ALEXANDER OODO ABAKPA English Language Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 7 KSTSB/R/20/027262 ALFRED SUNDAY Nil Government Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 8 KSTSB/R/20/003526 Aliyu Ibrahim Muhammad English Language Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 9 KSTSB/R/20/046574 Amos Jonah Government Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 10 KSTSB/R/20/006852 Amos Adiri Aminci Economics Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am Information Communication 9:00am to 11 KSTSB/R/20/001217 ANAS Aliyu Abba Technology (ICT) Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 12 KSTSB/R/20/001859 Andrew Sambo Matthew Computer Science Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am 9:00am to 13 KSTSB/R/20/001813 Ayuba Tambaya Emmanuel English Language Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am Christian Religion 9:00am to 14 KSTSB/R/20/003453 Bamaiyi Joseph Baba Knowledge Kafanchan 27-Jan-21 9:30am