Monograph No 17 Corrected File.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE 2008 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 31, 2008 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE ★ 44–748 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:54 Nov 06, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\45233.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska EDWARD R. ROYCE, California SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DONALD A. -

Scaling Authoritarian Information Control How China Adjusts the Level of Online Censorship

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348429732 Scaling Authoritarian Information Control How China Adjusts the Level of Online Censorship Article in Political Research Quarterly · January 2021 CITATIONS READS 0 102 2 authors: Rongbin Han Li Shao University of Georgia Zhejiang University 19 PUBLICATIONS 254 CITATIONS 7 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Self-censorship View project Cyber Criticism of Chinese Public Intellectuals View project All content following this page was uploaded by Li Shao on 19 January 2021. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Scaling Authoritarian Information Control How China Adjusts the Level of Online Censorship Rongbin Han Department of International Affairs, University of Georgia Address: 322 Candler Hall, University of Georgia, Athens GA 30602 Phone: 706-542-6705 Email: [email protected] Li Shao (Corresponding Author) Department of Political Science, School of Public Affairs, Zhejiang University Address: 634 School of Public Affairs, Zhejiang U Zijingang, Hangzhou, China 310068 Phone: 86-0592-5633-6986 Email: [email protected] 0 Abstract Autocracies can conduct “strategic censorship" online by selectively targeting different types of content, and by adjusting the level of information control. While studies have confirmed the state’s selective targeting behaviour in censorship, few have empirically examined how the autocracies may adjust the control level. Using data with a 6-year span, this paper tests whether the Chinese state scales up control over citizenry complaints in reaction to a series of socio-political events. -

China COI Compilation-March 2014

China COI Compilation March 2014 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation China COI Compilation March 2014 This COI compilation does not cover the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, nor does it cover Taiwan. The decision to exclude Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan was made on the basis of practical considerations; no inferences should be drawn from this decision regarding the status of Hong Kong, Macau or Taiwan. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2011 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:28 Oct 07, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR11FIN.TXT DEIDRE 2011 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:28 Oct 07, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 U:\DOCS\AR11FIN.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2011 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 68–442 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:28 Oct 07, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR11FIN.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, SHERROD BROWN, Ohio, Cochairman Chairman MAX BAUCUS, Montana CARL LEVIN, Michigan DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon SUSAN COLLINS, Maine JAMES RISCH, Idaho EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS SETH D. HARRIS, Department of Labor MARIA OTERO, Department of State FRANCISCO J. SA´ NCHEZ, Department of Commerce KURT M. -

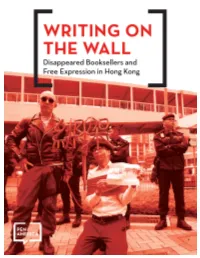

Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1

Writing on the Wall: Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1 WRITING ON THE WALL Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong November 5, 2016 © 2016 PEN America. All rights reserved. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect open expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible. Founded in 1922, PEN America is the largest of more than 100 centers of PEN International. Our strength is in our membership—a nationwide community of more than 4,000 novelists, journalists, poets, essayists, playwrights, editors, publishers, translators, agents, and other writing professionals. For more information, visit pen.org. Cover photograph: Artist Kacey Wong protests the Causeway Bay Books disappearances bound and gagged, sporting a red noose bearing the Chinese characters for "abduction." The sign in his hand says "Hostage is well. " Photo courtesy of Kacey Wong. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 “One Country, Two Systems” Under Threat ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Hong Kong’s Legal Framework -

Westminsterresearch Guiding Public Protest: Assessing the Propaganda

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Guiding public protest: assessing the propaganda model of China’s hybrid newspaper industry Bond, G. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr Graham Bond, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Guiding public protest: assessing the propaganda model of China’s hybrid newspaper industry Three case studies: the 2007 Xiamen PX Protest, the 2008 Chongqing Taxi Strike and the 2011 Wukan Land Protest Graham Bond A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 1 Abstract This dissertation presents an account and analysis of published mainland Chinese media coverage surrounding three major events of public protest during the Hu-Wen era (2003-2013). The research makes a qualitative analysis of printed material drawn from a range of news outlets, differentiated by their specific political and commercial affiliations. The goal of the research is to better understand the role of mainstream media in social conflict resolution, a hitherto under-studied area, and to identify gradations within the ostensibly monolithic mainland Chinese media on issues of political sensitivity. -

Tracking and Quantifying Censorship on a Chinese Microblogging Site

Tracking and Quantifying Censorship on a Chinese Microblogging Site Tao Zhu David Phipps Adam Pridgen Jedidiah R. Crandall Dan S. +allach [email protected] Computer Science Computer Science Computer Science Computer Science Independent Researcher Bowdoin College Rice Uni"ersity Uni"ersity of Ne% Mexico Rice Uni"ersity Abstract—We present measurements and analysis of censor- Since the media is heavily controlled in China, some current ship on Weibo, a popular microblogging site in China. Since e"ents do not appear in traditional media, and are not as we were limited in the rate at which we could download posts, prominent in social media as less sensiti"e topics are. +e we identified users likely to participate in sensitive topics and recursively followed their social contacts. We also leveraged new implemented a system which can find these current e"ents and natural language processing techniques to pick out trending the related discussions in social media before such content is topics despite the use of neologisms, named entities, and informal remo"ed for censorship reasons. +e ha"e de"eloped a user language usage in Chinese social media. tracking method for -nding sensiti"e topic posts before they We found that Weibo dynamically adapts to the changing are deleted. +e also apply no"el natural language processing interests of its users through multiple layers of filtering. he filtering includes both retroactively searching posts by keyword methods. To our kno%ledge, ours is the first system that can or repost links to delete them, and rejecting posts as they are successfully extract topics from posts that use unknown %ords posted. -

Methods of Online Information Control the Harvard Community

Fear, Friction, and Flooding: Methods of Online Information Control The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Roberts, Margaret Earling. 2014. Fear, Friction, and Flooding: Citation Methods of Online Information Control. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Accessed April 17, 2018 4:58:24 PM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12274299 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) ©2014 – Margaret Earling Roberts All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Gary King Margaret Earling Roberts Fear, Friction, and Flooding: Methods of Online Information Control Abstract Many scholars have speculated that censorship e↵orts will be ine↵ective in the information age, where the possibility of accessing incriminating information about almost any political entity will benefit the masses at the expense of the powerful. Others have speculated that while information can now move instantly across borders, autocrats can still use fear and intimidation to encourage citizens to keep quiet. This manuscript demonstrates that the deluge of information in fact still benefits those in power by observing that the degree of accessibility of information is still deter- mined by organized groups and governments. Even though most information is possible to access, as normal citizens get lost in the cacophony of information available to them, their consumption of information is highly influenced by the costs of obtaining it. -

Copyright by Robert Warren Wilson 2012

Copyright by Robert Warren Wilson 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Robert Warren Wilson Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A tear in my eye but I cannot cry: An ethnographic multiple case study on the language ecology of Urumchi, Xinjiang and the language practices of Uyghur young adults Committee: Luis Urrieta, Jr., Supervisor Arienne M. Dwyer Elaine K. Horwitz Angela M. Nonaka Deborah Palmer A tear in my eye but I cannot cry: An ethnographic multiple case study on the language ecology of Urumchi, Xinjiang and the language practices of Uyghur young adults by Robert Warren Wilson, B.A.; M.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of Charles Wilson and Nancy Koppen. Acknowledgements This dissertation study was a complex endeavor, and its realization would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of numerous people. I wish to thank the members of my dissertation committee: Dr. Luis Urrieta, Jr., Dr. Arienne Dwyer, Dr. Elaine Horwitz, Dr. Angela Nonaka, and Dr. Deborah Palmer. Thank you for your meaningful input. Through conversations and interactions with you, I had the honor of learning the meaning of rigorous social science. You have equipped me with the tools that I will use for the duration of my academic career. I thank Luis who invested a great deal of time and effort guiding this study and my development as a scholar. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2005 ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION 3, 2009 April v. Holder,OCTOBER 11, 2005on in Liv archived Cited Printed 05-70053for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China No. ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 23–753 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 19:18 Oct 07, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\23753.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa, Co-Chairman SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas DAVID DREIER, California GORDON SMITH, Oregon FRANK WOLF, Virginia JIM DEMINT, South Carolina JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania MEL MARTINEZ, Florida ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama MAX BAUCUS, Montana SANDER LEVIN, Michigan CARL LEVIN, Michigan MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota MICHAEL M. HONDA, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS STEVEN J. LAW, Department of Labor PAULA DOBRIANSKY, Department of State DAVID DORMAN, Staff Director (Chairman) JOHN FOARDE, Staff Director (Co-Chairman) (II) 3, 2009 April v. Holder, on in Liv archived Cited 05-70053 No. VerDate 11-MAY-2000 19:18 Oct 07, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\23753.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 C O N T E N T S Page I. -

The Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders & a Coalition Of

The Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders & a Coalition of Chinese NGOs Civil Society Report Submitted to The Committee against Torture (Committee) for its Review at the 56th Session of the fifth periodic report (CAT/C/CHN/5) by the People’s Republic of China on its Implementation of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel Inhuman or Degrading Treatment Or Punishment October 26, 2015 1 Executive Summary The People’s Republic of China has failed to implement specific articles of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention) during the current period of review—2009 to the present. Persistent lax implementation and enforcement of both the Convention and relevant domestic Chinese laws are linked to China’s one-party, authoritarian political system under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as well as the absence of rule of law and an independent judiciary. Legislative changes since 2009, which the State party has referred to repeatedly in its State report and its September 2015 response to the Committee’s List of Issues, have some positive provisions, but also many provisions that are likely to have a negative impact on the prevention of torture. Despite some encouraging new regulations and positive amendments to the Criminal and Criminal Procedure Laws, authorities have also provided for broader police powers and exceptions to provisions intended to protect human rights in the new National Security Law, draft Anti-Terrorism Law, and other draft laws and amendments. (Convention Articles 2, 11) In practice, torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and punishment remain persistent and widespread problems in China, especially in cases involving individuals whose views, speech, religious beliefs, or rights defense work are seen by the CCP as threats to its one-party rule (see appendix with list of detainees). -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2013 ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2013 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov 2013 ANNUAL REPORT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2013 ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2013 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 85–010 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House SHERROD BROWN, Ohio, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, MAX BAUCUS, Montana Cochairman CARL LEVIN, Michigan FRANK WOLF, Virginia DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MICHAEL M. HONDA, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS SETH D. HARRIS, Department of Labor FRANCISCO J. SA´ NCHEZ, Department of Commerce NISHA DESAI BISWAL, U.S. Agency for International Development LAWRENCE T. LIU, Staff Director PAUL B. PROTIC, Deputy Staff Director (II) CO N T E N T S Page I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................