Mary Oey New York University Some Problems in Musical Instrument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

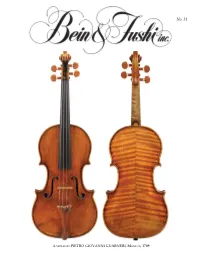

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

Early Music Review EDITIONS of MUSIC a Study That Is Complex, Detailed and Seems to Me to Reach Pretty Plausible Insights

Early Music Review EDITIONS OF MUSIC a study that is complex, detailed and seems to me to reach pretty plausible insights. His thesis in brief is ‘that the nativity of Christ is BOOKS represented in the first sonata in G minor while the juxtaposed D minor partita and C major sonata are the Ben Shute: Sei Solo: Symbolum? locus of passion-resurrection imagery.’ He acknowledges The Theology of J. S. Bach’s solo violin works that there have been both numerological and emotion- Pickwick Publications, Eugene, Oregon based interpretations in these areas, but none relying ISBN 978-1-4982-3941-7 on firm musicological bases. These he begins to lay out, xxvii+267pp, $28.00 undergirding his research with a sketch of the shift from thinking of music as en expression of the divine wisdom, his is not the first monograph to employ a variety an essentially Aristotelian absolute, towards music as a of disciplines to delve beneath the surface of a more subjective expression of human feeling, revealing the Tgroup of surviving compositions by Bach in the drama and rhetoric of the ‘seconda prattica.’ In Germany hope of finding a hidden key to their understanding and these two traditions – ratio and sensus – remained side by interpretation: nor will it be the last. But what is unusual side until the 18th century, and the struggle to balance the about Benjamin Shute is that he does not go overboard two is evident in Bach’s work. So stand-alone instrumental for the one-and-only solution, instead adopting a multi- music has a theological proclamation in its conviction faceted approach to unearthing the composer’s intentions. -

Edit Summer 2003

VOLUME THREE ISSUE TWO SUMMER 2003 EEDDiTiT TINKER TAILOR DOCTOR LAWYER EXCELLENCE PARTICIPATION WEALTH POVERTY INTELLIGENCE ADVANTAGE DISADVANTAGE EQUALITY LEADING THE WAY TO HIGHER EDUCATION Why wider access is essential for universities E D iTcontents The University of Edinburgh Magazine volume three issue two summer 2003 16 L 12 20 22 COVER STORIES 12 WIDENING PARTICIPATION Ruth Wishart’s forthright view of the debate 39 GENERAL COUNCIL The latest news in the Billet FEATURES 22 IMMACULATE COLLECTIONS Prof Duncan Macmillan looks at the University’s Special Collections 10 MAKING IT HAPPEN How a boy from Gorgie became Chairman of ICI REGULARS 04 EditEd News in and around the University publisher Communications & Public Affairs, 20 ExhibitEd Art at the Talbot Rice Gallery The University of Edinburgh Centre, 36 Letters As the new Rector is installed, a look at Rectors past 7-11 Nicolson Street, 27 InformEd Alumni interactions, past, present and future Edinburgh EH8 9BE World Service Alumni news from Auchtermuchty to Adelaide, or almost editor Clare Shaw 30 [email protected] design Neil Dalgleish at Hillside WELCOME TO the summer issue of EDiT. It’s an honour – and not a little daunting – to take over the editing of such [email protected] a successful magazine from Anne McKelvie, who founded the magazine, and Ray Footman, who ably took over the reins photography after Anne’s death. Tricia Malley, Ross Gillespie at broad dayligh 0131 477 9211 Enclosed with this issue you’ll find a brief survey. Please do take a couple of minutes to fill it in and return it. -

Antonio Stradivari "Servais" 1701

32 ANTONIO STRADIVARI "SERVAIS" 1701 The renowned "Servais" cello by Stradivari is examined by Roger Hargrave Photographs: Stewart Pollens Research Assistance: Julie Reed Technical Assistance: Gary Sturm (Smithsonian Institute) In 184.6 an Englishman, James Smithson, gave the bines the grandeur of the pre‑1700 instrument with US Government $500,000 to be used `for the increase the more masculine build which we could wish to and diffusion of knowledge among men.' This was the have met with in the work of the master's earlier beginning of the vast institution which now domi - years. nates the down‑town Washington skyline. It includes the J.F. Kennedy Centre for Performing Arts and the Something of the cello's history is certainly worth National Zoo, as well as many specialist museums, de - repeating here, since, as is often the case, much of picting the achievements of men in every conceiv - this is only to be found in rare or expensive publica - able field. From the Pony Express to the Skylab tions. The following are extracts from the Reminis - orbital space station, from Sandro Botticelli to Jack - cences of a Fiddle Dealer by David Laurie, a Scottish son Pollock this must surely be the largest museum violin dealer, who was a contemporary of J.B. Vuil - and arts complex anywhere in the world. Looking laume: around, one cannot help feeling that this is the sort While attending one of M. Jansen's private con - of place where somebody might be disappointed not certs, I had the pleasure of meeting M. Servais of Hal, to find the odd Strad! And indeed, if you can manage one of the most renowned violoncellists of the day . -

Some Misconceptions About the Baroque Violin

Pollens: Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin Some Misconceptions about the Baroque Violin Stewart Pollens Copyright © 2009 Claremont Graduate University Much has been written about the baroque violin, yet many misconceptions remain²most notably that up to around 1750 their necks were universally shorter and not angled back as they are today, that the string angle over the bridge was considerably flatter, and that strings were of narrower gauge and under lower tension.1 6WUDGLYDUL¶VSDWWHUQVIRUFRQVWUXFWLQJQHFNVILQJHUERDUGVEULGJHVDQG other fittings preserved in the Museo Stradivariano in Cremona provide a wealth of data that refine our understanding of how violins, violas, and cellos were constructed between 1666- 6WUDGLYDUL¶V\HDUV of activity). String tension measurements made in 1734 by Giuseppe Tartini provide additional insight into the string diameters used at this time. The Neck 7KHEDURTXHYLROLQ¶VWDSHUHGQHFNDQGZHGJH-shaped fingerboard became increasingly thick as one shifted from the nut to the heel of the neck, which required the player to change the shape of his or her hand while moving up and down the neck. The modern angled-back neck along with a thinner, solid ebony fingerboard, provide a nearly parallel glide path for the left hand. This type of neck and fingerboard was developed around the third quarter of the eighteenth century, and violins made in earlier times (including those of Stradivari and his contemporaries) were modernized to accommodate evolving performance technique and new repertoire, which require quicker shifts and playing in higher positions. 7KRXJK D QXPEHU RI 6WUDGLYDUL¶V YLROD DQG FHOOR QHFN SDWWHUQV DUH SUHVHUYHG LQ WKH 0XVHR Stadivariano, none of his violin neck patterns survive, and the few original violin necks that are still mounted on his instruments have all been reshaped and extended at the heel so that they could be mortised into the top block. -

Violin Detective

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS instruments have gone up in value after I found that their soundboards matched trees known to have been used by Stradivari; one subsequently sold at auction for more than four times its estimate. Many convincing for- KAMILA RATCLIFF geries were made in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the science did not exist then. Forgers now are aware of dendro- chronology, and it could be a problem if they use wood from old chalets to build sophisti- cated copies of historical instruments. How about unintentional deceit? I never like to ‘kill’ a violin — reveal it as not what it seems. But if the wood does not match the claims, I investigate. I was recently sent photos of a violin supposedly made by an Italian craftsman who died in 1735. The wood dated to the 1760s, so I knew he could not have made it. But I did see strong cor- relations to instruments made by his sons and nephews who worked in the 1770s. So Peter Ratcliff restores and investigates violins from his workshop in Hove, UK. I deduced that the violin might have been damaged and an entirely new soundboard made after the craftsman’s death. The violin Q&A Peter Ratcliff was pulled from auction, but not before it had received bids of more than US$100,000. Will dendrochronology change the market? Violin detective I think it already has, and has called into Peter Ratcliff uses dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — to pin down the age and suggest the question some incorrect historical assump- provenance of stringed instruments. -

Stradivari Violin Manual

Table of Contents 1. Disclaimer .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Welcome .................................................................................................................... 2 3. Document Conventions ............................................................................................... 3 4. Installation and Setup ................................................................................................. 4 5. About STRADIVARI VIOLIN ........................................................................................ 6 5.1. Key Features .................................................................................................... 6 6. Main Page .................................................................................................................. 8 7. Snapshots ................................................................................................................ 10 7.1. Overview of Snapshots ................................................................................... 10 7.2. Saving a User Snapshot ................................................................................. 10 7.3. Loading a Snapshot ......................................................................................... 11 7.4. Deleting a User Snapshot ............................................................................... 12 8. Articulation .............................................................................................................. -

Tuning Ancient Keyboard Instruments - a Rough Guide for Amateur Owners

Tuning Ancient Keyboard Instruments - A Rough Guide for Amateur Owners. Piano tuning is of course a specialized and noble art, requiring considerable skill and training. So it is presumptuous for me to offer any sort of Pocket Guide. However, it needs to be recognized that old instruments (and replicas) are not as stable as modern iron-framed pianos, and few of us can afford to retain the services of a professional tuner on a frequent basis. Also, some of us may be restoring old instruments, or making new ones, and we need to do something. So, with apologies to the professionals, here is a short guide for amateurs. If you know how to set a temperament by ear, and know what that means, please read no further. But if not, a short introductory background might be useful. Some Theory We have got used to music played in (or at least based around) the major and minor scales, which are in turn descended from the ancient modes. In these, there are simple mathematical ratios between the notes of the scale, which are the basis of our perception of harmony. For example, the frequency of the note we call G is 3/2 that of the C below. This interval is a pure, or perfect fifth. When ratios are not exact, we hear ‘beats’, as the two notes come in and out of phase. For example, if we have one string tuned to A415 (cycles per second, or ‘Hertz’ and its neighbour a bit flat at A413, we will hear ‘wow-wow-wow’ beats at two per second. -

Giovanni Ferrini Dell’Accademia Internazionale Giuseppe Gherardeschi Di Pistoia

Ottaviano Tenerani LO SPINETTONE FIRMATO GIOVANNI FERRINI DELL’ACCADEMIA INTERNAZIONALE GIUSEPPE GHERARDESCHI DI PISTOIA Presso l’Accademia Internazionale d’Organo e di Musica Antica Giuseppe Gherardeschi di Pistoia si conserva uno spinettone apparentemente realiz- zato nel 1731 da Giovanni Ferrini (fig. 1).1 Figura 1. Lo spinettone di Pistoia, Accademia Internazionale d’Organo e di Musica Antica ‘Giuseppe Gherardeschi’. Foto dell’autore. 1 Questo strumento è già stato descritto in Stewart Pollens, ‘Three keyboard instruments signed by Cristofori’s assistant, Giovanni Ferrini’, The Galpin Society Journal XLIV, 1991, 77–93: 80 e sgg. Si veda anche Stewart Pollens, Bartolomeo Cristofori and the invention of the 111 Ottaviano Tenerani Si tratta di uno dei tre strumenti di questo tipo attualmente conosciuti, insieme ai suoi consimili attribuiti rispettivamente a Bartolomeo Cristofori (Museum für Musikinstrumente der Universität Leipzig, Lipsia, inv. n. 86) e al pisano Giuseppe Solfanelli (Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Washington D.C., inv. n. 60.1395).2 In questo breve scritto si renderà conto della storia del ritrovamento dello strumento di Pistoia, del suo ripristino funzionale e dei contesti ad oggi conosciuti riguardanti il suo utilizzo storico. Partendo dalle differenze tra i tre spinettoni ad oggi noti, proporremo inoltre alcune riflessioni sul suo funzionamento e sul possibile uso musicale dei registri, in particolare del 4 piedi. Origine dello strumento La storia del ritrovamento di questo strumento inizia nei primissimi anni Sessanta del Novecento quando il Capitolo di Pistoia decise di mettere in vendita il materiale che si trovava nelle soffitte del duomo, in locali a fine- stratura aperta e quindi parzialmente esposti alle intemperie. -

Guide to the Dowd Harpsichord Collection

Guide to the Dowd Harpsichord Collection NMAH.AC.0593 Alison Oswald January 2012 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: William Dowd (Boston Office), 1958-1993................................................ 4 Series 2 : General Files, 1949-1993........................................................................ 8 Series 3 : Drawings and Design Notes, 1952 - 1990............................................. 17 Series 4 : Suppliers/Services, 1958 - 1988........................................................... -

II IAML Annual Conference

IAML Annual Conference Edinburgh II 6 - I I August 2000 International Association of Music Libraries,Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Association Internationale des Bibliothèques,Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren (IVBM) Contents 3 Introduction: English 13 Einleitung: Deutsch 23 Introduction: Français 36 Conference Programme 51 IAML Directory 54 IAML(UK) Branch 59 Sponsors IAML Annual Conference The University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, Scotland 6 - I I August 2000 International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Association Internationale des Bibliothèques,Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren (IVBM) oto: John Batten Without the availability of music libraries, I would never have got to know musical scores. They are absolutely essential for the furtherance of musical knowledge and enjoyment. It is with great pleasure therefore that I lend my support to the prestigious conference of IAML which is being hosted by the United Kingdom Branch in Edinburgh. I am delighted as its official patron to commend the 2000 IAML international conference of music librarians' Sir Peter Maxwell Davies Patron: IAML2000 5 II Welcome to Edinburgh Contents We have great pleasure in welcoming you to join us in the 6 Conference Information beautiful city of Edinburgh for the 2000 IAML Conference. 7 Social Programme Events during the week will take place in some of the 36 Conference Programme city's magnificent buildings and Wednesday afternoon tours 5I IAML Directory are based on the rich history of Scotland.The Conference 54 IAML(UK) Branch sessions as usual provide a wide range of information to 59 Sponsors interest librarians from all kinds of library; music is an international language and we can all learn from the experiences of colleagues. -

The Basics of Harpsichord Tuning Fred Sturm, NM Chapter Norfolk, 2016

The Basics of Harpsichord Tuning Fred Sturm, NM Chapter Norfolk, 2016 Basic categories of harpsichord • “Historical”: those made before 1800 or so, and those modern ones that more or less faithfully copy or emulate original instruments. Characteristics include use of simple levers to shift registers, relatively simple jack designs, use of either quill or delrin for plectra, all-wood construction (no metal frame or bars). • 20th century re-engineered instruments, applying 20th century tastes and engineering to the basic principle of a plucked instrument. Pleyel, Sperrhake, Sabathil, Wittmeyer, and Neupert are examples. Characteristics include pedals to shift registers, complicated jack designs, leather plectra, and metal frames. • Kit instruments, many of which fall under the historical category. • A wide range of in between instruments, including many made by inventive amateurs. Harpsichords come in many shapes and designs. • They may have one keyboard or two. • They may have only one string per key, or as many as four. • The pitch level of each register of strings may be standard, or an octave higher or lower. These are called, respectively, 8-foot, 4-foot, and 16-foot. • The harpsichord may be designed for A440, for A415, or possibly for some other pitch. • Tuning pins may be laid out as in a grand piano, or they may be on the side of the case. • When there are multiple strings per note, the different registers may be turned on and off using levers or pedals. We’ll start by looking at some of these variables, and how that impacts tuning. Single string instruments These are the simplest instruments, and the easiest to tune.