Final Solution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizensâ•Ž Motives Near

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Proceedings of the Tenth Annual MadRush MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference Conference: Best Papers, Spring 2019 From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush Part of the European History Commons, and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons Green, Jordan, "From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust" (2019). MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference. 1. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/madrush/2019/holocaust/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conference Proceedings at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in MAD-RUSH Undergraduate Research Conference by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Complaisance to Collaboration: Analyzing Citizens’ Motives Near Concentration and Extermination Camps During the Holocaust Jordan Green History 395 James Madison University Spring 2018 Dr. Michael J. Galgano The Holocaust has raised difficult questions since its end in April 1945 including how could such an atrocity happen and how could ordinary people carry out a policy of extermination against a whole race? To answer these puzzling questions, most historians look inside the Nazi Party to discern the Holocaust’s inner-workings: official decrees and memos against the Jews and other untermenschen1, the role of the SS, and the organization and brutality within concentration and extermination camps. However, a vital question about the Holocaust is missing when examining these criteria: who was watching? Through research, the local inhabitants’ knowledge of a nearby concentration camp, extermination camp or mass shooting site and its purpose was evident and widespread. -

Déportés À Auschwitz. Certains Résis- Tion D’Une Centaine, Sont Traqués Et Tent Avec Des Armes

MORT1943 ET RÉSISTANCE BIEN QU’AYANT rarement connu les noms de leurs victimes juives, les nazis entendaient que ni Zivia Lubetkin, ni Richard Glazar, ni Thomas Blatt ne survivent à la « solution finale ». Ils survécurent cependant et, après la Shoah, chacun écrivit un livre sur la Résistance en 1943. Quelque 400 000 Juifs vivaient dans le ghetto de Varsovie surpeuplé, mais les épi- démies, la famine et les déportations à Treblinka – 300 000 personnes entre juillet et septembre 1942 – réduisirent considérablement ce nombre. Estimant que 40 000 Juifs s’y trouvaient encore (le chiffre réel approchait les 55 000), Heinrich Himmler, le chef des SS, ordonna la déportation de 8 000 autres lors de sa visite du ghetto, le 9 janvier 1943. Cependant, sous la direction de Mordekhaï Anielewicz, âgé de 23 ans, le Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ZOB, Organisation juive de combat) lança une résistance armée lorsque les Allemands exécutèrent l’ordre d’Himmler, le 18 janvier. Bien que plus de 5 000 Juifs aient été déportés le 22 janvier, la Résistance juive – elle impliquait aussi bien la recherche de caches et le refus de s’enregistrer que la lutte violente – empêcha de remplir le quota et conduisit les Allemands à mettre fin à l’Aktion. Le répit, cependant, fut de courte durée. En janvier, Zivia Lubetkin participa à la création de l’Organisation juive de com- bat et au soulèvement du ghetto de Varsovie. « Nous combattions avec des gre- nades, des fusils, des barres de fer et des ampoules remplies d’acide sulfurique », rapporte-t-elle dans son livre Aux jours de la destruction et de la révolte. -

The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo" (2016). Student Publications. 438. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/438 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 438 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History, Historical Fiction, and Historical Myth: 'The German Doctor' by Lucía Puenzo Abstract The se cape of thousands of war criminals to Argentina and throughout South America in the aftermath of World War II is a historical subject that has been clouded with mystery and conspiracy. Lucía Puenzo's film, The German Doctor, utilizes this historical enigma as a backdrop for historical fiction by imagining a family's encounter with Josef Mengele, the notorious SS doctor from Auschwitz who escaped to South America in 1949 under a false identity. -

Simplified WWII Timeline

~ Belz Museum of Asian and Judaic Art ~ Holocaust Memorial Gallery ~ Simplified World War II Timeline 1933 JANUARY 30, 1933 German President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler chancellor. At the time, Hitler was leader of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi party). FEBRUARY 27-28, 1933 The German parliament (Reichstag) building burned down under mysterious circumstances. The government treated it as an act of terrorism. FEBRUARY 28, 1933 Hitler convinced President von Hindenburg to invoke an emergency clause in the Weimar Constitution. The German parliament then passed the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of Nation (Volk) and State, popularly known as the Reichstag Fire Decree, the decree suspended the civil rights provisions in the existing German constitution, including freedom of speech, assembly, and press, and formed the basis for the incarceration of potential opponents of the Nazis without benefit of trial or judicial proceeding. MARCH 22, 1933 The SS (Schutzstaffel), Hitler's “elite guard,” established a concentration camp outside the town of Dachau, Germany, for political opponents of the regime. It was the only concentration camp to remain in operation from 1933 until 1945. By 1934, the SS had taken over administration of the entire Nazi concentration camp system. MARCH 23, 1933 The German parliament passed the Enabling Act, which empowered Hitler to establish a dictatorship in Germany. APRIL 1, 1933 The Nazis organized a nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned businesses in Germany. Many local boycotts continued throughout much of the 1930s. APRIL 7, 1933 The Nazi government passed the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which excluded Jews and political opponents from university and governmental positions. -

SS-Totenkopfverbände from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history SS-Totenkopfverbände From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from SS-Totenkopfverbande) Navigation Not to be confused with 3rd SS Division Totenkopf, the Waffen-SS fighting unit. Main page This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. No cleanup reason Contents has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (December 2010) Featured content Current events This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding Random article citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2010) Donate to Wikipedia [2] SS-Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), rendered in English as "Death's-Head Units" (literally SS-TV meaning "Skull Units"), was the SS organization responsible for administering the Nazi SS-Totenkopfverbände Interaction concentration camps for the Third Reich. Help The SS-TV was an independent unit within the SS with its own ranks and command About Wikipedia structure. It ran the camps throughout Germany, such as Dachau, Bergen-Belsen and Community portal Buchenwald; in Nazi-occupied Europe, it ran Auschwitz in German occupied Poland and Recent changes Mauthausen in Austria as well as numerous other concentration and death camps. The Contact Wikipedia death camps' primary function was genocide and included Treblinka, Bełżec extermination camp and Sobibor. It was responsible for facilitating what was called the Final Solution, Totenkopf (Death's head) collar insignia, 13th Standarte known since as the Holocaust, in collaboration with the Reich Main Security Office[3] and the Toolbox of the SS-Totenkopfverbände SS Economic and Administrative Main Office or WVHA. -

Operation Reinhard: Death Camps What’S Included

World War Two Tours Operation Reinhard: Death Camps What’s included: Hotel Bed & Breakfast All transport from the official overseas start point Accompanied for the trip duration All Museum entrances All Expert Talks & Guidance Low Group Numbers “Amazing time, one of those ‘once in a life time trips’. WelI organised, very interesting and thoroughly enjoyable. I would recommend the trip to any enthusiast.” Operation Reinhard (German: Aktion Reinhard or Einsatz Reinhard) was the code name given to the Nazi plan to murder Polish Jews in the General Government, and marked the most deadly phase of the Holocaust, the use of extermination camps. During the operation, as many as two Military History Tours is all about the ‘experience’. Naturally we take million people were murdered in Bełżec, Sobibor and Treblinka, almost all of whom were Jews. care of all local accommodation, transport and entrances but what By 1942, the Nazis had decided to undertake the Final Solution. sets us aside is our on the ground knowledge and contacts, established This led to the establishment of camps such as Bełżec, over many, many years that enable you to really get under the surface of Sobibor and Treblinka which had the express purpose of killing your chosen subject matter. thousands of people quickly and efficiently. These sites differed By guiding guests around these from those such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek because historic locations we feel we are contributing greatly towards ‘keeping they also operated as forced-labour camps, these were purely the spirit alive’ of some of the most killing factories. The organizational apparatus behind the memorable events in human history. -

Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland

Miranda Walston Witnessing Extermination: Using Diaries to Understand the Final Solution in Poland Honours Thesis By: Miranda Walston Supervisor: Dr. Lauren Rossi 1 Miranda Walston Introduction The Holocaust spanned multiple years and states, occurring in both German-occupied countries and those of their collaborators. But in no one state were the actions of the Holocaust felt more intensely than in Poland. It was in Poland that the Nazis constructed and ran their four death camps– Treblinka, Sobibor, Chelmno, and Belzec – and created combination camps that both concentrated people for labour, and exterminated them – Auschwitz and Majdanek.1 Chelmno was the first of the death camps, established in 1941, while Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzec were created during Operation Reinhard in 1942.2 In Poland, the Nazis concentrated many of the Jews from countries they had conquered during the war. As the major killing centers of the “Final Solution” were located within Poland, when did people in Poland become aware of the level of death and destruction perpetrated by the Nazi regime? While scholars have attributed dates to the “Final Solution,” predominantly starting in 1942, when did the people of Poland notice the shift in the treatment of Jews from relocation towards physical elimination using gas chambers? Or did they remain unaware of such events? To answer these questions, I have researched the writings of various people who were in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” I am specifically addressing the information found in diaries and memoirs. Given language barriers, this thesis will focus only on diaries and memoirs that were written in English or later translated and published in English.3 This thesis addresses twenty diaries and memoirs from people who were living in Poland at the time of the “Final Solution.” Most of these diaries (fifteen of twenty) were written by members of the intelligentsia. -

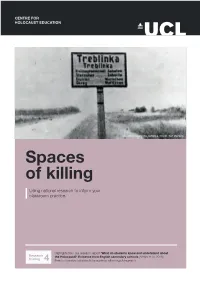

Spaces of Killing Using National Research to Inform Your Classroom Practice

CENTRE FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATION The entrance sign to Treblinka. Credit: Yad Vashem Spaces of killing Using national research to inform your classroom practice. Highlights from our research report ‘What do students know and understand about Research the Holocaust?’ Evidence from English secondary schools (Foster et al, 2016) briefing 4 Free to download at www.holocausteducation.org.uk/research If students are to understand the significance of the Holocaust and the full enormity of its scope and scale, they need to appreciate that it was a continent-wide genocide. Why does this matter? The perpetrators ultimately sought to kill every Jew, everywhere they could reach them with victims Knowledge of the ‘spaces of killing’ is crucial to an understanding of the uprooted from communities across Europe. It is therefore crucial to know about the geography of the Holocaust. If students do not appreciate the scale of the killings outside of Holocaust relating to the development of the concentration camp system; the location, role and purpose Germany and particularly the East, then it is impossible to grasp the devastation of the ghettos; where and when Nazi killing squads committed mass shootings; and the evolution of the of Jewish communities in Europe or the destruction of diverse and vibrant death camps. cultures that had developed over centuries. This briefing, the fourth in our series, explores students’ knowledge and understanding of these key Entire communities lost issues, drawing on survey research and focus group interviews with more than 8,000 11 to 18 year olds. Thousands of small towns and villages in Poland, Ukraine, Crimea, the Baltic states and Russia, which had a majority Jewish population before the war, are now home to not a single Jewish person. -

Sobibór: Sobibór Holocaust Propaganda and Reality Sobibór

BARNES REVIEW HOLOCAUST HANDBOOK SERIES • VOLUME 19 19 BARNES REVIEW HOLOCAUST HANDBOOK SERIES • VOLUME 19 SOBIBÓR: SOBIBÓR HOLOCAUST PROPAGANDA AND REALITY SOBIBÓR HOLOCAUST PROPAGANDA AND REALITY n May 2009, 89-year-old Cleveland autoworker John Demjanjuk was de- ported from the United States to Germany, where he was arrested and HOLOCAUST PROPAGANDA AND REALITY Icharged with aiding and abetting murder in at least 27,900 cases. These mass murders were allegedly perpetrated at the Sobibór “death” camp in east- ern Poland. According to mainstream historiography, 170,000 to 250,000 Jews were exterminated there in gas chambers between 1942 and 1943. The corpses were buried in mass graves and later incinerated on an open-air pyre. But do these serious claims really stand up to scrutiny? In Sobibor: Holocaust Propaganda and Reality, the official version of what transpired at Sobibór is put under the microscope. It is shown that the histori- ography of the camp is not based on solid evidence, but on the selective use of eyewitness testimonies, which in turn are riddled with contradictions and out- right absurdities. This book could exonerate John Demjanjuk. For more than half a century, mainstream Holocaust historians made no real attempts to muster material evidence for their claims about Sobibór. Finally, in the 21st century, professional historians carried out an archeological survey at the former camp site. Their findings—and the findings of many oth- ers—are here presented in detail and fatal implications for the extermination camp theory are revealed. SOBIBOR: HOLOCAUST PROPAGANDA AND REALITY (softcover, 434 pages, indexed, illustrated, #536, $25 minus 10% for TBR subscribers) can be ordered from TBR BOOK CLUB, P.O. -

Market Intelligence for Russia and CIS 1 1/2010 GIA Geographies White Paper Paper White GIA Geographies

1/2010 Market Intelligence for Paper White GIA Geographies Russia and CIS GIA Geographies White Paper 1/2010 “Now it is a very good time to en- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ter into the Russian market. There The wealthiest market per capita of all BRIC countries, Russia com- bines the best of Europe and Asia. Together with the Commonwealth of are some niches and free space in Independent States (CIS), it represents a market of around 300 million the market due to the crisis. There consumers and offers many opportunities not only for multinationals but also for middle-size players. is market share to be captured. According to my estimations this The best time to enter the Russian market is probably now, when compa- nies can look for opportunities during periods of turmoil and crisis. Pos- easy-to-enter market situation will sibly this will be the last chance for a while for good expansion opportuni- last a year or two...” ties. In one or two years, the window will close and it will be necessary to either invest heavily at the entry stage or develop more slowly. “...Mentally and culturally Rus- Mentally and culturally Russian people are Europeans, which means more comfortable conditions for Western businesses if compared to some other sian people are Europeans, which developing markets. means more comfortable conditions Russia is not only a big market; it offers also huge intellectual and creative for Western businesses here.” potential for those looking for R&D and innovations. Along with traditional intelligence challenges for emerging markets, spe- See below more details about doing cific issues face an entrant to the Russian market: business in Russia, from an interview • Russian market having been relatively open, the competition is rather tough by now, even though the crisis has opened up niches with Vsevolod Gavrilov, • specific economic structures and business models remain as a Head of Russian Office, handicap from Soviet times Volvo Penta Corporation Deep market analysis and a sophisticated approach to the market entry strategy are required from newcomers. -

ENGLISH Original: RUSSIAN Delegation of the Russian Federation

PC.DEL/97/18 1 February 2018 ENGLISH Original: RUSSIAN Delegation of the Russian Federation STATEMENT BY MR. ALEXANDER LUKASHEVICH, PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION, AT THE 1174th MEETING OF THE OSCE PERMANENT COUNCIL 1 February 2018 In response to the address by the Chair of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance Mr. Chairperson, I should like to take this opportunity to express our support for the successful OSCE conference on anti-Semitism, which was held in Rome on 29 January. Mr. Galizia, We thank you for your insightful address. Seventy-three years ago Red Army soldiers liberated the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp, also known as Oświęcim. In 2005, the United Nations officially proclaimed 27 January International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust. I should also like to recall that on 27 January we marked the 74th anniversary of the complete liberation of Leningrad from the Nazi siege. This was yet another act of heroism by Soviet soldiers, before whom we bow our heads. Soviet troops brought a halt to one of the “death factories” in which up to 4 million people, including around a million Jews, had been systematically exterminated. All told, more than 6 million people became victims of the Holocaust. For the peoples of Russia, as for the other peoples of the multi-ethnic Soviet Union, who sacrificed more than 26 million lives for victory in the Second World War, the preservation of the historical memory of these terrible events remains a national responsibility. Jews themselves made a significant contribution to the victory over Nazism. -

Special Motivation - the Motivation and Actions of the Einsatzgruppen by Walter S

Special Motivation - The Motivation and Actions of the Einsatzgruppen by Walter S. Zapotoczny "...Then, stark naked, they had to run down more steps to an underground corridor that Led back up the ramp, where the gas van awaited them." Franz Schalling Einsatzgruppen policeman Like every historical event, the Holocaust evokes certain specific images. When mentioning the Holocaust, most people think of the concentration camps. They immediately envision emaciated victims in dirty striped uniforms staring incomprehensibly at their liberators or piles of corpses, too numerous to bury individually, bulldozed into mass graves. While those are accurate images, they are merely the product of the systematization of the genocide committed by the Third Reich. The reality of that genocide began not in the camps or in the gas chambers but with four small groups of murderers known as the Einsatzgruppen. Formed by Heinrich Himmler, Reichsfuhrer-SS, and Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), they operated in the territories captured by the German armies with the cooperation of German army units (Wehrmacht ) and local militias. By the spring of 1943, when the Germans began their retreat from Soviet territory, the Einsatzgruppen had murdered 1.25 million Jews and hundreds of thousands of Polish, Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian and Soviet nationals, including prisoners of war. The Einsatzgruppen massacres preceded the invention of the death camps and significantly influenced their development. The Einsatzgruppen story offers insight into a fundamental Holocaust question of what made it possible for men, some of them ordinary men, to kill so many people so ruthlessly. The members of the Einsatzgruppen had developed a special motivation to kill.