Architecture I Theory I Criticism I History Atch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allora Pharmacy I Have Witnessed Quite a Few Near Misses with People Trying to Contributes to High Blood Pressure and High Cholesterol

Issue No. 3525 The AlloraPublished by OurNews Pty. Ltd.,Advertiser at the Office, 53 Herbert Street, Allora, Q. 4362 “Since 1935” Issued Weekly as an Advertising Medium to the people of Allora and surrounding Districts. Your FREE Local Ph 07 4666 3089 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web www.alloraadvertiser.com Wednesday, 9th January, 2019 Op Shop Open Under New Banner Bob Burge, Trevor Shields and Nev Laney from Allora Men’s Shed convert the Blue Care Cottage to enable clothing and other goods to be suitably displayed. The Allora Op Shop, members of the Allora previously operated on Men’s Shed, the Blue Care behalf of Blue Care re- cottage has been renovated opened on Tuesday under to enable volunteers to organise the display of the auspices of the local Scope Club members Jill (kneeling) Heather, Lynn and Helen set up Scope Club. clothing and other items. the banner in preparation for the first day of trading under the new With the support of name. good honest service 572 Condamine River Road, PRATTEN 432 ha A Rare Gem in a Magnificent Setting Location, charm and production versatility very seldom are delivered in one parcel. Previously • John Dalton architecturally designed five bedroom homestead the home of a successful Santa Gertrudis stud, this property has only changed hands twice • Air-conditioned and combustion heating with two formal lounges since settlement. • Fully ensuited guest-room, fully screened verandahs, magnificent views over the Mount Manning offers the capability of breeding and backgrounding with the added bonus Condamine River of fertile irrigated river flats with undulating grazing country. -

Hansard 5 April 2001

5 Apr 2001 Legislative Assembly 351 THURSDAY, 5 APRIL 2001 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. R. K. Hollis, Redcliffe) read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. PETITIONS The Clerk announced the receipt of the following petitions— Western Ipswich Bypass Mr Livingstone from 197 petitioners, requesting the House to reject all three options of the proposed Western Ipswich Bypass. State Government Land, Bracken Ridge Mr Nuttall from 403 petitioners, requesting the House to consider the request that the land owned by the State Government at 210 Telegraph Road, Bracken Ridge be kept and managed as a bushland reserve. Spinal Injuries Unit, Townsville General Hospital Mr Rodgers from 1,336 petitioners, requesting the House to provide a 24-26 bed Acute Care Spinal Injuries Unit at the new Townsville General Hospital in Douglas currently under construction. Left-Hand Drive Vehicles Mrs D. Scott from 233 petitioners, requesting the House to lower the age limit required to register a left-hand drive vehicle. Mater Children's Hospital Miss Simpson from 50 petitioners, requesting the House to (a) urge that Queensland Health reward efficient performance, rather than limit it, for the high growth population in the southern corridor, (b) argue that Queenslanders have the right to decide where their child is treated without being turned away, (c) decide that the Mater Children’s Hospital not be sent into deficit for meeting the needs of children who present at the door and (d) review the current funding system immediately to remedy this. PAPERS MINISTERIAL PAPER The following ministerial paper was tabled— Hon. R. -

Ajejii|U&Jc but Never Heard; Efficiently You'll Graduate in Dull on Predigested Tidbits of Solemnity

5c-A* ^f^ He wants a brave new University, Forget your songs, runs the Wh(jr e undergrads will all decree be kept In cages; — Students should be seen And there they will be fed >ajejii|u&jc but never heard; efficiently You'll graduate in dull On predigested tidbits of solemnity. the wisdom of the THE U.Q.U. NEWSPAPER Now "Gaudeamus" is de- ages. dared a dirty word. Regtstered at tl>e C.P.O., Brisbans. lor Friday, April 28, 1961 transmission by post as a periodical. Volume 31, No. 4 Atithorised by J. Fogarty and J. B. Dalton, c^^nlversify Union Offices, St. Lucia. Printed by Watson, Ferguson and Co., Stanley Street, Soulh Brisbane iiiiiMi^iMiriiiiiG: Mr. Bishopp said that pranks he considered in "I'll really fix things for us," he said. bad taste were squirting policemen with a solu "I'll issue the force with new orders. No tion of chewing guna and arsenic, or sinking arresting Varsity men. If any cops are sprayed American ships. with bubble gum and arsenic they must stand still He said that the until their flat feet develop tinea. first mentioned prank "No interfering with any pranks at all by was "shocking" as the Varsity men. Anything is allowed at the proces poor policemen's flat sion. Smut, nudes, politics, smut — say maybe feet were glued to the we could do a float on the joke about the old priest and the young priest. "Just so we'll be safe I'll get all the bodgies ground with the gum/ rounded up for the week. -

Constructing a Modern Architectural Identity in Rural Queensland

The Distance between Myth and Reality: Constructing a Modern Architectural Identity in Rural Queensland Elizabeth Musgrave University of Queensland From the 1960s, the projection of an Australian architectural identity, nationally and internationally, drew from myths surrounding white settlement and centred on the settler homestead in its rural setting—notwithstanding the facts of a highly urbanised population and an increasingly pluralist architectural setting. This paper will reflect on the distance that opens up for the architect between architectural intentions linked to faithfully reconstructing images of identity and the facts of the individual architecture project. It will address these issues by introducing one project, “Morocco” (1963), a house for Stan and Noela Wippell, located on the floodplain of the Balonne River in the western Darling Downs, Queensland. The paper will then compare “Morocco” with contemporaneous and subsequent , edited , edited architecturally design homesteads by the architect, John Dalton, as well as other Australian architects. By 1963, Dalton had built a series of homestead “style” houses in the dry, sclerophyll forested suburbs of west Brisbane. However, “Morocco” required the homestead “style” be negotiated with the reality of the “outback.” The gap between romantic myth and the reality of station-life manifested itself in very , Distance Looks Back Proceedings of the Society of Proceedings of the Society of 36 prosaic matters. The proposed paper will address literal and figurative distance; the distance between the ideal image and particular circumstance; and between myth and fact: the glamorisation of the bush myth and the problems brought about by remoteness. It reveals that mythologies of settlement provided a wealth of material for grounding paradigms in a specific place. -

Continuing the Lauries Journey

www.slcoldboys.com.au On College Hill Continuing the Lauries Journey The Official Publication of the St Laurence’s College Old Boys’ Association June/July 2019 Mailing Address: SLOBA Registrar SLOBA Registrar Phone: 07 3010 1178 St Laurence’s College Email: [email protected] 82 Stephens Road South Brisbane QLD 4101 A Publication of the St Laurence’s College Old Boys’ Association—June/ July 2019 Page 1 On College Hill Continuing the Laurie’s Journey In this Edition From the Association 3 From the Foundation 4 A Message from Chris—College Principal 5 SLOBACare 6 Q3 /4 2019 Key Dates 7 Save the Date—Reunion Weekend 8 Mikel Mellick (‘89) - The Psychology of Sport 9 Our Latest Honorary Life Members 14 The Runcorn Project Update 17 On the Board at #1—John Dalton (‘52) 17 Back to Runcorn Day Old Boys Challenge 19 Back to Runcorn Function 21 Know your History—Take the Crossword Challenge 23 “Woody Cup” Report 24 College Cultural and Sporting Update 28 College Anzac and Race Day 31 On the Grapevine…. 32 We Pray 33 Plus, Our Service Record, 2021 Year 5 intake deadline, College Corporate Lunch and the 2019 Musical, “The Addams Family” and From the Past…... 2019 Committee: President: Peter Wendt (‘88); Vice-President—Antoni Raiteri (‘84); Secretary—Michael Campbell (‘72); Treasurer—Chris Webster (‘69)/ Michael Campbell (‘72); Junior Vice-President—Jock Scahill (‘10); Registrar—Helen Turner; Committee—Di Taylor (Life Member); Denis Brown (’59), Chris Skelton (‘78), John Dinnen (‘78), Anthony Samios (‘80), Scott Stanford (‘89), Cameron Wigan (‘95), Steve Leszczynski (‘96), John O’Brien (‘98) A Publication of the St Laurence’s College Old Boys’ Association—June/ July 2019 Page 2 On College Hill Continuing the Laurie’s Journey From the Association Peter Wendt (’88) - President Welcome to our mid year newsletter - I hope you find it to be an enjoyable and informative read. -

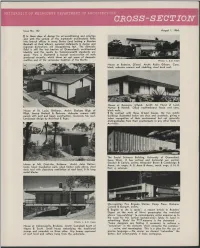

Cross-Section, Aug 1964 (No

NIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE CROSS-S if In these days of design for air-conditioning and prestige and with the spread of the mammoth architectural firms into branch offices in many States (and lacking a Gordon Bunshaft at their elbow), personal statements in design and regional distinctions are disappearing fast. The domestic field is still the last bastion of Queensland's architectural identity and the results by Commonwealth standards are good. Here is illustrated a typical cross-section of work produced recently, which shows an apt sense of domestic realities and of the vernacular tradition of the North: Photo: L. & D. Keen House at Buderim, Q'land. Archt: Robin Gibson. Conc. block, asbestos cement wall cladding, steel deck roof. House at Kenmore, Q'land. Archt: M. Hurst of Lund, Hutton & Newell. Oiled weatherboard fascia and conc. House at St. Lucia, Brisbane. Archt: Graham Bligh of block walls. Bligh, Jessup Bretnall & Partners. Asbestos cement infill By contrast with these Q'land houses, the two public panels with post and beam construction. Concrete tile roof. buildings illustrated below are dour and uncertain, giving a Landscape design by Architect B. Ryan. token recognition of their environment but not generally distinguishable from their counterparts in any other State in Aus+ralia: The Social Sciences Building, University of Queensland, faces West. It has vertical and horizontal sun control. Goodsir & Carlyle, archts; Alexander Brown & Cambridge & House at Mt. Coot-tha, Brisbane. Archt. John Dalton. Assoc., str. engrs; A. E. Axon & Assoc., mech. engr; J. H. B. Conc. block foundation walls, oiled timber walls above, steel Kerr, q. -

First Placegetters in the Queensland Scholarship Examination 1873-1962

Promising lives: First placegetters in the Queensland Scholarship examination 1873-1962 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics at the University of Queensland in December 2006. Marion Elizabeth Mackenzie BA, BSW, PGDip(Arts) Statement of originality I certify that this thesis is original and my own work, except where the work of others is quoted and acknowledged as such in the text. This material has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other university. Abstract The Scholarship was an external examination held at the end of primary school when students were generally aged thirteen or fourteen. It dominated Queensland education for ninety years from 1873 until 1962. For much of that period, passing the examination was the only opportunity for most children to enter secondary education. It was at first a competitive examination for limited places in the early grammar schools, and later a qualifying examination for entrance to any secondary school. The principal focus of this thesis is the early promise displayed by 186 young Queenslanders who were ranked first in the state in the examination. It draws conclusions about the impact of education on individuals and society through longitudinal research, by examining the influence of family, school, community attitudes, world events and personal choices on the outcomes for those successful students. It investigates how early success was translated into their later lives, how they dealt with the opportunities and barriers they encountered, whether females and males had different outcomes, and in what ways they differed from their peers. -

John Dalton's 1970S Campus

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand Vol. 32 Edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan Published in Sydney, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2015 ISBN: 978 0 646 94298 8 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Musgrave, Elizabeth. “Structuring Space for Student Life: John Dalton’s 1970s Campus Commissions.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions and Change, edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan, 446-456. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015. All efforts have been undertaken to ensure that authors have secured appropriate permissions to reproduce the images illustrating individual contributions. Interested parties may contact the editors. Elizabeth Musgrave, University of Melbourne and University of Queensland Structuring Space for Student Life: John Dalton’s 1970s Campus Commissions This paper investigates the way in which a rethinking of pedagogical philosophies during the 1960s and 1970s might have informed the architecture of the educational institutions themselves. It will describe four projects from the office of John Dalton Architect and Associates on campuses of higher education in South East Queensland that resulted from the rapid expansion of the sector in the 1960s in Australia and that embody the spirit of innovation within the sector at that time. These works – which include the Art, Craft and Music Teaching Building (1970-74) at the Darling Downs Institute of Advanced Education; University House (1972) at Griffith University, Campus Nathan; the Halls of Residence at Kelvin Grove Teachers Training College (1974); and the Bardon Professional Development Centre (1975) – explore architectural solutions for models of education introduced into Queensland in the 1970s and reveal Dalton’s interest in place, in the idea of community and in the capacity of architectural form to structure social and educational interactions. -

Student Residences QUT Kelvin Grove Campus Conservation Management Plan

Student Residences QUT Kelvin Grove Campus Conservation Management Plan ROBERT RIDDEL ARCHITECT Student Residences QUT Kelvin Grove Campus Conservation Management Plan December 2004 ROBERT RIDDEL ARCHITECT 7 Diddams Lane Petrie Bight PO Box 1267 Fortitude Valley Q 4006 Ph 38314155 Fax 38314150 email [email protected] CONTENTS 1 Introduction .................................................1 The study team ........................................1 2 Historical overview............................................2 Technical education in Queensland ........................2 Kelvin Grove hall of residence............................3 Subsequent changes to the complex .......................6 The site today.........................................6 3 Significance of site ............................................8 Assessing cultural heritage significance .....................8 Statement of significance ................................9 Discussion of significance ................................9 Schedule – elements of significance .......................10 4 Conservation policies .........................................12 The Burra Charter.....................................12 The significance of the site ..............................13 Qualified personnel....................................13 Materials and method of repair..........................13 Removal of fixtures and fittings ..........................13 Interpretation.........................................14 Planning and spatial relationships.........................14 -

UQFL 499 John Dalton Architectural Plans

FRYER LIBRARY Manuscript Finding Aid UQFL 499 John Dalton Architectural Plans Size 17 tubes of 278 plans, 1 box, 5 folders, 1 album Contents Architectural drawings, and notes, correspondence and photographs from John Dalton's architectural practice. Biography John Dalton was a leading figure in architecture in Queensland between 1956, when he graduated, and 1979, when he temporarily retired from the field. Widely respected by his peers and the winner of numerous industry awards, Dalton was known for his distinctive approach to the challenges of designing for the Queensland climate. Some of his best-known works were his own residence, Dalton House, at Fig Tree Pocket, the Vice-Chancellor's Residence at the University of Queensland, University House at Griffith University and the Bardon Professional Centre. He was a prolific contributor to architectural journals and served for a time as the Queensland correspondent for Architecture in Australia. Notes Open access Box 1 John Dalton Architect & Associates, Griffith University Community Services Building Specification, Jun 1973 Folder 1 Elizabeth Musgrave-Price, architectural notes and correspondence, 1993 to 2004 Folder 2 35mm negatives, large format negatives, photographs floor plan and display board for Dalton House, Fig Tree Pocket Folder 3 Colour photographs of Wilson House, Mt.Coot-tha Display board templates for residences including: Last updated: 17/08/2020 © University of Queensland 1 FRYER LIBRARY Manuscript Finding Aid • Wilson House, Toowong, 1964 • Graham House, Toowong, 1967 • Peden House, Moggill, 1975 Folder 4 Proof copy of Elizabeth Musgrave article, ‘Architectural Image and Idiom: Making Local’, Mosaic : a Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, Dec 2004, Vol.37(4), pp.255-273 (includes note from Elizabeth Musgrave), newspaper cuttings, 2004 Folder 5 Typescript index of John Dalton’s architectural work, 13p Folder 6 Annotated copies of journal articles relating to architecture, 1960 to 1968 Copy of Dalton’s profile excerpted from Emanuel M. -

The Ashgrovian

THE ASHGROVIAN THE ASHGROVIAN Vol 52 - No 1 The Official Publication of Marist College Ashgrove Old Boys Association Inc. FIRST EDITION 2014 LLEGE O AS H C T G S R I O R V A E M After completing the above, please post to: Marist Old Boys Association, PO Box 82, Ashgrove QLD 4060 PAYMENT O My “not negotiable” cheque, payable to Marist College Ashgrove Old Boys Assoc. is enclosed. OR Bankcard Mastercard Visa Expiry Date / S Card Number: L Name on Card: _______________________________________________________________________________________ Y Cardholder’s Signature: ___________________________________________ Phone No: _________________________ D B O T H E A S H G R O V I A N PRESIDENT TREASURER John O’HARE Anthony COLLINS 1964-1972 (Jane) 1973-1978 (Joanne) P: 07 3369 4860; W 07 3366 3559 P: 3366 0871; W: 3229 5448 M: 0417 336 977 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] VICE-PRESIDENT SECRETARY Dominick MELROSE Peter CASEY 1985-1992 (Rebecca) 1966-1974 (Linda) P: 07 3851 2828; M: 0430 030 044 M: 0438 325 863 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] COMMITTEE Brad BUTTEN Stuart LAING (1979-1981) (Kaley) 1969-1977 (Louise) Phone: 07 3122 1748 P: 07 3366 5188; M 0428 709 733 Mobile: 0412 672 750 E: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Jack LARACY Jim GARDINER 1945-1953 (Karin) 1972-1980 (Kath) P: 07 3300 1622 P: 07 33667005; M: 0410 565 800 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Chris SHAY Sean HARKIN 1985-1989 (Ann-Maree) 1972-1980 (Maria) P 07 3356 5728; M 0412 228 565 H: 07 3366 6270; M: 0401 137 048 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Mark KIERPAL 1981-1988 (Martine) P: 07 3352 5275; W 07 3118 0600 M: 0400 517 745 E: [email protected] DATES TO REMEMBER 2014 Friday 15 August - VINTAGE BLUE & GOLD LUNCH for classes from 1940 to 1974 Sunday 14 September - Old Boys Annual Race Day Friday 3 October - REUNION MASS AND EVENING FUNCTION at the Cyprian Pavilion Check the Old Boys website at www.ashgroveoldboys.com.au for further details. -

Quoting Ian Ferrier (1928-2000) Contributing to Queensland’S Post-War Modern Church Architecture

QUOTATION: What does history have in store for architecture today? Quoting Ian Ferrier (1928-2000) Contributing to Queensland’s Post-war Modern Church Architecture Lisa Marie Daunt The University of Queensland Abstract Post-war church buildings are often among the most interesting modern architectural works. However, limited recognition has hitherto been afforded to Queensland’s post-war churches and their architects. Located in the (sub)tropical north-eastern corner of the country, the post-war churches in this state share an affinity with their European and North American predecessors, whilst at the same time expressing a clear need to respond to the local, hot and humid climate. This paper researches how Ian Ferrier, a Brisbane-based architect, who designed approximately thirty ecclesiastical buildings from Tweed Heads to Port Moresby between the 1950s and the 1980s struck a balance between international influences and regional responses in his religious designs. In a 1999 interview conducted by local architectural historians Fiona Gardiner and Alice Hampson, Ferrier stated: 'there is little churches of mine fluttering everywhere'. This statement appears excessively modest. Ferrier was one of the most prominent and most progressive Catholic Church architects in post-war Queensland who fully seized the opportunities that the liturgical movement and the Second Vatican Council afforded to rethink ecclesiastical design. Strangely enough, later in the interview, he quite boastfully claimed: 'I pride myself in, I was one of the very first to recognise the climate in Queensland, particularly North Queensland, as different from the climate in England’. The son of a Scottish father and a French mother, Ferrier studied architecture in Canada and only moved to Queensland in 1955, at the age of 26.Ferrier’s background and his own appraisal of his architectural work explain the unique blending of the international and the local recognisable in his church designs.