Building Inclusive Supply Chains: LESSONS LEARNED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© All About Planners 1

PEN COMPARISON PILOT SAKURA STAEDTLER ZEBRA PAPERMATE Fineliner Pilot Frixion Fineliner Pen Sakura Pigma Micron Pen Triplus Fineliner 0.3mm Zebra Zensations Sarasa Flair UF (Ultra Fine) Pilot Drawing Pen 0.8mm Fineliner Pen 0.8mm Flair M (Medium) Zebra Mackee Care Refillable Double-Sided Marker Extra Fine/Fine Gel Pen Pop’Lol 0.7mm Gelly Roll Maxum Gel Ink Pens 0.4, Sarasa Clip 0.5mm Inkjoy Gel 0.7 Juice Up 0.4mm Ballsign 0.5mm 0.5mm G2 Gel Pen 0.7mm Ballpoint Pen Acroball 0.5mm, S20 ballpoint Grasso Ball Ballpoint 0.7mm Concrete Ballpoint Pen - Retractable - 0.7mm Inkjoy 100 Ball 1.0M 0.7mm medium point 1mm Mini Ballpoint pen - 0.7mm Kilometrico Emulsion Ink - 0.7mm InkJoy 300RT Ballpoint Dual Tip Pen Futayaku Double-sided Brush No Twin-tip handwriting pens 3mm Mildliner Double-Sided No Pen Fine/Medium & 0.8mm Highlighter Brush Needle Tip Hi-Tec C Maica 0.4mm Sakura Pigma Micron No Liquid Rollerball Needle Pen - No 0.5mm Marker Pen Pilot Lettering Pen Sakura Pigma Calligrapher Pen Triplus Broadliner 0.8mm Sarasa Fineliner No Erasable Frixion Erasable 0.3, 0.35, 0.4, No No No Replay Erasable Gel Pen (but I 0.5, 0.7 & 0.9mm don’t recommend) Refillable Frixion Erasable No No No No Colors available Does it have a white Pop’Lol 0.7mm Gelly Roll No Yes No pen? Bright Pop’Lol 0.7mm Gelly Roll Moonlight Bright Triplus 0.3mm Fineliners Yes Yes Fluorescent Pastel Pop’Lol 0.7mm Gelly Roll Souffle Triplus 0.3mm Fineliners Yes Yes Neon Pop’Lol 0.7mm Gelly Roll Triplus 0.3mm Fineliners Yes No Metallic G2 Gel Pen 0.7mm Gelly Roll Metallic, Stardust Metallic Markers Yes PM300 Gel Performance Prone to ghosting or No Light ghosting Light ghosting No No bleed through? (Based on majority of pens from this brand) How long does the ink Depends how often you use Have had for 3+ years and ink Have had for 3+ years and ink Have had for 3+ years and ink Have had gel & ballpoint pens last? them. -

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015

New Summary Report - 26 June 2015 1. How did you find out about this survey? Other 17% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% Email from Renaissance Art 83.1% 539 Other 17.0% 110 Total 649 1 2. Where are you from? Australia/New Zealand 3.2% Asia 3.7% Europe 7.9% North America 85.2% North America 85.2% 553 Europe 7.9% 51 Asia 3.7% 24 Australia/New Zealand 3.2% 21 Total 649 2 3. What is your age range? old fart like me 15.4% 21-30 22% 51-60 23.3% 31-40 16.8% 41-50 22.5% Statistics 21-30 22.0% 143 Sum 20,069.0 31-40 16.8% 109 Average 36.6 41-50 22.5% 146 StdDev 11.5 51-60 23.3% 151 Max 51.0 old fart like me 15.4% 100 Total 649 3 4. How many fountain pens are in your collection? 1-5 23.3% over 20 35.8% 6-10 23.9% 11-20 17.1% Statistics 1-5 23.3% 151 Sum 2,302.0 6-10 23.9% 155 Average 5.5 11-20 17.1% 111 StdDev 3.9 over 20 35.8% 232 Max 11.0 Total 649 4 5. How many pens do you usually keep inked? over 10 10.3% 7-10 12.6% 1-3 40.7% 4-6 36.4% Statistics 1-3 40.7% 264 Sum 1,782.0 4-6 36.4% 236 Average 3.1 7-10 12.6% 82 StdDev 2.1 over 10 10.3% 67 Max 7.0 Total 649 5 6. -

Boy Meets Girl PARIS — Masculine-Feminine Tailoring Returned to the Runways for Fall

The Inside: Pg. 14 NIKE PROFIT DROPS/3 LAMONICA TO EXIT KORS/3 Women ofWWD Leisure WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’THURSDAY Daily Newspaper • March 20, 2003 Vol. 185, No. 57 $2.00 List Sportswear Boy Meets Girl PARIS — Masculine-feminine tailoring returned to the runways for fall. And some of the best of it came from Viktor Horsting and Rolf Snoeren, whose terrific Viktor & Rolf collection was full of skillful riffs on their favorite men’s styles, among them cool pantsuits, big-collared jackets and jeans. The presentation was also inventive, with the designers’ muse, Tilda Swinton, appearing on the catwalk and the other models done up to resemble her. Here, a Tilda lookalike wears a bold-collared blouse and pants. For more on the haberdashery trend, see pages 6 and 7. From Red Carpet Roll-up To Economic Anxieties, Industry Braces for War olding its breath. As the nation Hrolled toward war in Iraq, fashion and retail executives were waiting on Wednesday to see the impact of a conflict everyone hopes will be a short one. The situation already has shaken one of the fashion industry’s biggest events: the Oscars. As reported, the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences has canceled the traditional red-carpet parade of stars — which some consider the world’s most-watched fashion show — in favor of a low-key event focused on the awards rather than the dresses and diamonds. Party organizers, including See Industry, Page16 PHOTO BY PHOTO GIOVANNI BY GIANNONI 2 WWDTHURSDAY Sportswear GENERAL FASHION: The notion of using men’s haberdasherylooks for women resurfaces 6 every few years, as it did for fall. -

BBB-Summer-2018-Large.Pdf

‘Modern’ calligraphy has been making the rounds lately and if you're here — that's probably what you want to learn! But before we get all into the details, here's one thing you need to remember: calligraphy is not cursive. Cursive is joined up writing; you ideally write without li�ting your pen so you can write faster. While calligraphy can look similar, the key is to go slow and to break down each and every letter into its supporting strokes. THE BASIC STROKES ASCENDER LINE WAIST LINE BASE LINE DESCENDER LINE Or as some people call them, the drills! As dull as it sounds, brush lettering is made up of 9 common strokes illustrated above. With these strokes alone, you can form 21 out of the 26 letters in the lowercase alphabet — and some of the capital letters too! HOW THIS WORKS In Brush Basics, we'll be building your foundation right by covering all 9 strokes over the course of 2 weeks! Here's the schedule: On Day 1, you'll learn how to use your brush pen to form thin upstrokes and thick downstrokes. This is an easy lesson, so you have just one day to tackle it! Lesson 2 (delivered on Day 2) will cover underturn and overturn strokes. Lessons 3 and 4 (delivered on Days 4 and 6, respectively) will see you taking on the two di�ferent compound curves. You'll learn all about ovals in Lesson 5 (delivered on Day 8) — and because this is a hard one, you'll have not two but three days to practice it. -

Printmgr File

LISTING CIRCULAR NOT FOR GENERAL CIRCULATION IN THE UNITED STATES New Look Secured Issuer plc New Look Senior Issuer plc £1,201,200,000 (equivalent) £700,000,000 6.5% Senior Secured Notes due 2022 €415,000,000 Floating Rate Senior Secured Notes due 2022 £200,000,000 8.0% Senior Notes due 2023 New Look Secured Issuer plc (the “Senior Secured Notes Issuer”) issued £700,000,000 aggregate principal amount of its 6.5% Sterling Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes due 2022 (the “Sterling Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes” or the “Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes”) and €415,000,000 aggregate principal amount of its Floating Rate Senior Secured Notes due 2022 (the “Floating Rate Senior Secured Notes” and, together with the Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes, the “Senior Secured Notes”). New Look Senior Issuer plc (the “Senior Notes Issuer” and, together with the Senior Secured Notes Issuer, the “Issuers”) issued £200,000,000 aggregate principal amount of its 8.0% Senior Notes due 2023 (the “Senior Notes” and, together with the Senior Secured Notes, the “Notes”). The Senior Secured Notes Issuer will pay interest on the Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes semi-annually in arrears on each May 15 and November 15, commencing on November 15, 2015. Prior to June 24, 2018, the Senior Secured Notes Issuer may redeem at its option all or a portion of each series of the Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes by paying a “make-whole” premium. At any time on or after June 24, 2018, the Senior Secured Notes Issuer may redeem at its option all or part of the Fixed Rate Senior Secured Notes by paying a specified redemption price. -

Tokyo Pocket Guide Ginza Map Shopping Tokyo Pocket Guide Ginza Map Shopping

TOKYO POCKET GUIDE GINZA MAP SHOPPING Dr Regal UGG Martens MARUNOUCHI Setouchi Mizuho MAP A B C J. Ferry D Vera Eikokuya E Hiroshima Bank F G Kokusai Wang Harry Imperial International Winston Forum TOKYO STATION Diamond 1 Theater Lucie MAP J. Ferry Jacadi Yogibo Quil Shirashi Conv Hills Intimissimi Caran’d Ginza Global Ache Fai Bon Ralph Lauren 1 B3 4 Ave Okura Pelle Puzzle Melsa Minx M0851 4º Bridal Morbida 5 Ginza G-Star Raw Albore Ishikawa Iqos Facade Toraya B2 Gloss Miu Miu Agete The Estanation Gold Double Eagle Ermernegildo Tokyo Tiffany Kotsu Inz 2 Loft Bridge BIC ABC Kashiyama Adolfo Il Bisonte Dunhill & Co Daichi Kaikan Mart Dominguez Camera Fugetsudo Semei Marronnier Repetto 2 Bldg Chopard Nanan Aoyama 2 New Tokyu Itoya Marrioner Banana Itoya 2 Yurakucho Hands Rep Burberry V88 Okura Bldg Gate 2 Miki Moncler Bldg House Cartier Tourist Moto Bvlgaria Imperial Info Palace Forum Max COS Marrioner Gate 2 Mara Chanel Exit Graff CHUO-dori ave Louis Ishii Spajiro Vuitton B1 Uniqlo Nitori Sports Muji Akio Mori Oioi Moon Star Tag Heuer Inz 1 MUJI Coco (Marui) Queen’s Hotel Moku Meganeya Meister Way Neko Neko Lazare Diamond Sanshin Toei Pelie Kaikan Cinema Ecco Morbida Van Cleef & Arpels A13 JS Luxe 9.999 Plaza 3 Police RT Tabasa Chaumet 3 Sotobori-dori Ave Gregory Dakota Akris Matsuya Ginza Atmos Ships Rangetsu Univ Trading LaYamano Loro Tiana Ginza Exit Diesel Lacoste Post Yurakucho Language Hublot Cole Beauty Azuma St. Bldg Ginza Shiseido Base A12 Taisho Itocia Glasse Astalift 45R Apm Haan Apple Seimei SB’s Genten Hibiya MCM Furla BK Church -

Building the Future the Newsletter of MIAA Educational Athletics

Focus on Game Lifelong Bonds Generations Officials celebrate Another benefit together Sportsmanship of sports Summit features participation GWS Day 2020 panel p. 7 p. 9 p. 12 Building the Future the newsletter of MIAA Educational Athletics Summer 2020 MIAA/MSAA Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Summit held at Framingham State he Massachusetts Interscholastic and cultural competency and mental goals that we established at the Athletic Association (MIAA) health disparities. Mike Rubin, MIAA / start of this inclusion mission were Tand the Massachusetts School MSAA Assistant Director said, “Two to promote diversity and encourage Administrators’ participation, interaction Association (MSAA) held and understanding in its third annual Diversity, our increasingly diverse Equity and Inclusion (DEI) society.” Summit at Framingham Summit presenters State University on included members of Monday, January 13, the MIAA/MSAA DEI 2020. With over 240 Committee, which consists attendees representing of school administrators, 65 schools, the 2020 supporting agencies, Summit featured eight and representatives concurrent workshops from higher education covering subjects institutions, as well as including: impact of race individuals from the MIAA on daily life, para-sports, Partners in Prevention, inclusive strategies, a powerful collaborative Unified Champion schools, of public and private Leadership and content providers for this year’s Diversity, Equity and working to undo bias Inclusion Summit included, from left, Joseph Walsh, President, Adaptive prevention agencies. and end hate, creating Sports New England; Dr. Dwayne Thomas, Associate Professor of Sports The Committee and the safe and supportive Management, Lasell University; Mike Rubin, MIAA/MSAA Assistant Director; Collaborative provide Dr. F. Javier Cevallos, President, Framingham State University; Yvonne M. -

Art Supplies Pencil Sharpeners: Recommendations to Choose From: Desktop Pencil Sharpener: Some Brands Are: Muji, Carl Angel-5 (R

Spring Flowers in Colored Pencil and Watercolor – ONLINE Wendy Hollender Art Supplies Pencil Sharpeners: Recommendations to choose from: Desktop pencil sharpener: some brands are: Muji, Carl Angel-5 (Rodahle or Q- Connect Desktop Hand held pencil sharpener: Faber Castell Pencil sharpener in a box. 1 or 2 Graphite pencils. H lead. I like Tombow H pencil. Erasers: Kneaded eraser Tombow Mono round Zero Eraser Tombow Mono Colored Pencil Eraser Small see thru Ruler for measuring: Westcott See – thru ruler Colored pencils: Faber-Castell polychromos colored pencils Cadmium Yellow 107 Cadmium Yellow Lemon 205 Pale Geranium Lake 121 Middle Purple Pink 125 Ultramarine 120 Cobalt Turquoise 153 Permanent Green Olive 167 Earth Green Yellowish 168 Earth Green 172 Dark Cadmium Orange 115 Purple Violet 136 Dark Sepia 175 Dark Indigo 157 Chrome Oxide Green 278 Red Violet 194 White 101 Ivory 103 Warm Grey IV 273 Burnt Ochre 187 Venetian Red 190 Light Yellow Ochre 183 Burnt Sienna 283 Madder 142 Olive Green Yellowish 173 Bistre 170 Dark Flesh 130 Faber-Castell Albrect Durer Watercolour Pencils: These have the same color names as the Faber Castell polychromos. Middle Purple Pink 125 Permanent Green Olive 167 Dark Cadmium Orange 115 Pale Geranium Lake 121 Purple Violet 136 Dark Sepia 175 Cadmium Yellow 107 Burnt Sienna 283 White 101 Light Yellow Ochre 183 Warm Gray IV 273 Earth Green 172 Ultramarine 120 Brushes: Watercolor brushes by Interlon in sizes: 0/3, 0, 6 Or Waterbrush from Pentel Or your own set of preferred watercolors and brushes. Collapsible Water Cup by Faber Castell or other small container to hold water. -

The Influence of SPA Model on Muji and Its Consumers in China

2020 International Conference on World Economy and Project Management (WEPM 2020) The Influence of SPA Model on Muji and its Consumers in China Wang Mengjie Dongbei University of Finance and Economics [email protected] Keywords: SPA Model, Muji, Supply Chain, Service, Customers Abstract: Fashion retailers such as Uniqlo and Zara and grocery brands such as Muji have become increasingly popular in recent years. In addition to the superior location factor, they all use the SPA model for sales. Taking Muji as an example, this report studies the positive and negative effects of adopting SPA model and puts forward suggestions for future development of Muji. This report collects primary data through questionnaires and uses secondary data to accomplish research objectives. The conclusion of this project is that the SPA model support Muji to achieve good relationships with consumers, but there are still problems that are not in line with the national conditions on the road of Muji to enter China. Therefore, this report puts forward some suggestions on how to localize SPA model in order that Muji can capture market demand and then attract potential consumers. 1. Introduction 1.1 Research background With the improvement of economic level and income, shopping has become one of the most prevailing ways for people to enjoy themselves. Fashion retailers such as ZARA, Uniqlo and grocery brands represented by Muji are welcome among young people. One important reason is that when customers give their feedback to the merchants, they can quickly respond to meet their demands. This system is called the SPA model. SPA model is a vertically integrated system that integrates product planning, manufacturing and retail. -

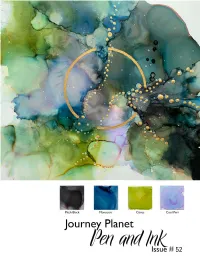

Journey Planet

52 Table of Contents Pages Welcome 2 Alcohol Ink... Sara Felix 3 Iroshizuku Take- Sumi Ink 5 for Instance... James Bacon Enabler.... John Dodd 7 In Praise of Doodling.... Helen Montgomery 11 Harvest Moon... Ann Gry 14 Envelope Art... Marguerite Smith 16 A Southpaws Guide to Pens... John Vaughan 17 The Ink Stuff I have been doing... Chris Garcia 24 Pen Dragon... Rhonda Eudaly 26 Thank you for the art that was provided for this issue. Chris Garcia, Sara Felix, Ann Gry, Vanessa Applegate, Helen Montgomery, and Marguerite Smith and all the lovely picture of pens and mail from John Dodd, James Bacon, Ann Gry and John Vaughan. Welcome Ink. Versatile memory sharing art medium. I’m very grateful to all our contributors here they gave us time during this tricky year and it’s lovely to see Welcome to this issue of journey planet. such wonderfulness. Chris and I are especially thankful to Sara for coming on board to co-edit this issue we are I’m really so pleased that Sara Felix came onboard to so impressed with the wonderful layout the extensive co-edit this issue which looks at ink. use of art and also helping us to find and solicit such great pieces of work. Sara is an incredible force in I’ve loved Sara’s artwork over the years and as her fandom, especially so when it comes to the promotion own work in ink developed and then Chris also of artists, running the Chesley awards her own work started to use ink as an artistic medium I realised that being recognised as a Hugo finalist and when she’s there is an incredible bond between these fluids that asked to make incredible awards we are very lucky and become permanent on paper and our experiences and grateful to have such a versatile artist give their time to memories of the now. -

Everyday Life – Signs of Awareness

PRESS RELEASE 2017.8.4 150th Year Anniversary of Japan - Denmark Diplomatic Relations Exhibition Everyday Life – Signs of Awareness 2017.8.5 (Sat.) - 2017.11.5 (Sun.) Exhibition Title 150th Year Anniversary of Japan - Denmark Diplomatic Relations Exhibition Everyday Life – Signs of Awareness Period Saturday August 5 – Sunday November 5, 2017 / 10:00 - 18:00 (until 20:00 on Fridays and Saturdays). Note: Tickets available until 30 minutes before closing Closed: Mondays, (open on August 14, September 18, October 9 and October 30), and September 19 (Tue.), October 10(Tue.) Venue 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa Number of Exhibited Works 282 (Galleries 7-12, 14), Courtyard, Public Zone Curated by Kurosawa Hiromi, Chief Curator of 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa / Cecilie Manz, Designer Admission Adult: ¥1,000 (¥800) / University: ¥800 (¥600) / Elem/JH/HS: ¥400 (¥300) / 65 and over: ¥800 *( ) indicate advance ticket and group rates (20 or more) Advance Tickets: Ticket PIA (Tel +81-[0]0570-02-9999: [Exhibition ticket P code] 768-377) Lawson Ticket (Tel +81-[0]0570-000-777: [Exhibition ticket L code] 52171) Organized by 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa [Kanazawa Art Promotion and Development Foundation] Supported by The Ministry of Culture Denmark / The Committee for Craft and Design, Project Funding, Danish Arts Foundation / Royal Danish Embassy / Hokkoku Shimbun Company Grants from The Scandinavia-Japan Sasakawa Foundation International patrons Kvadrat / Louis Poulsen / Maersk Line / Scan Global Logistics / Actus Co., Ltd. / Nissin Furniture Crafters Co., Ltd. Sponsored by Bang & Olufsen Japan / Ohizumibussan / Kimura Glass In cooperation with Fukumitsuya Sake Brewery / Scandinavian Airlines / NIHON HOUSE HOLDINGS Co., Ltd. -

Internationella Reservoarpennmärken

Internationella reservoarpennmärken Sammanställning av inläggen i tråden http://www.fountainpennetwork.com/forum/topic/281024-pen-brands-worldwide-by-country/ samt egna tillägg Argentina: 303 Ariel Kullock Artcraft Birome Cadillac Contador Ducal Escorial Escritor Everton Federal Giavota (Swan) Gauchada (made in England) Ilasa Inflapen L'Extol Morrison Morrison Ducal Muñeca New Yorker Parker (Argentine factory) Perfecta Princesa Punta de Oro Pyrmont Ralen Rapidograf River Sheaffer (Argentine factory) Silvatrim Soñada Sylvapen Wembley Yenson 1 Austria: Executiv Pen Champion Elite Jolly Konig Marvel Sauga Sonnenblick Myrna Australia: Curtis Dasi D:Scribe Dominium (Taskovski) Parker (Australian factory) Sheaffer (Australian factory) Taskovski Belgium: Belgor Bermond Conid Flandria Le Tigre Merle Blanc Mercury (Dammaerts) Mercury (Dubois Vutera) Pelletier Stabil Valeria Matta (Dubois Vutera) Victory Vis-o-ray Bulgaria: Chaika Canada: Adanac Deluxe 2 Eatonia Esterbrook (Canadian factory) Hooded Knight (Eclipse Toronto) Monroe North-Rite Parker (Canadian factory) Shaeffer (Canadian factory) Streamline (Eclipse) Waterman (Canadian factory) Zephyr (Eclipse Toronto) China: Airman Anda 安達 Angel (Wing Sung) Baoer (or Bao'er; Shanghai Qian Gu Stationary Co Ltd) 保爾 Baoke Beifa Beijing Bookworm Boshi 博士 (Golden Star) Bulow Cadence Camel Chang Hong 長虹 Changjiang 長江 Charm Crocodile 金鱷 Crown 皇冠 Da Gong (or Dagong; Wuhan Pen Factory) 大公 Dah Loh Dandong Dannitu Danyutu 丹玉兔 Dewen Diamond (Heilongjiang) 鑽石 Dibao Dikawen Dinuoyang Doctor (Hero) Dolce Vita Naranja Donghong 東虹 Dongsheng 東升 3 Dong Yi 東藝 Duke (Golden Crown) 公爵 Farn Fenghua 豐華 Flight Flourish (Jinli) 金利 Fuliwen G.Crown (Duke) General (Youlian) 將軍 Gentleman Ginkoshen Golden Dragon (Dandong) 金龍 Gold Star Golden Star Guanleming Guangli 廣利 Guangrong 光榮 Guanleming (or Wm.