Sperrylite Ptas2 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Cubic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Podiform Chromite Deposits—Database and Grade and Tonnage Models

Podiform Chromite Deposits—Database and Grade and Tonnage Models Scientific Investigations Report 2012–5157 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey COVER View of the abandoned Chrome Concentrating Company mill, opened in 1917, near the No. 5 chromite mine in Del Puerto Canyon, Stanislaus County, California (USGS photograph by Dan Mosier, 1972). Insets show (upper right) specimen of massive chromite ore from the Pillikin mine, El Dorado County, California, and (lower left) specimen showing disseminated layers of chromite in dunite from the No. 5 mine, Stanislaus County, California (USGS photographs by Dan Mosier, 2012). Podiform Chromite Deposits—Database and Grade and Tonnage Models By Dan L. Mosier, Donald A. Singer, Barry C. Moring, and John P. Galloway Scientific Investigations Report 2012-5157 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 This report and any updates to it are available online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2012/5157/ For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Mosier, D.L., Singer, D.A., Moring, B.C., and Galloway, J.P., 2012, Podiform chromite deposits—database and grade and tonnage models: U.S. -

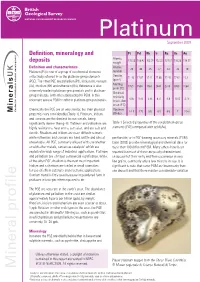

Mineral Profile

Platinum September 2009 Definition, mineralogy and Pt Pd Rh Ir Ru Os Au nt Atomic 195.08 106.42 102.91 192.22 101.07 190.23 196.97 deposits weight opme vel Atomic Definition and characteristics 78 46 45 77 44 76 79 de number l Platinum (Pt) is one of a group of six chemical elements ra UK collectively referred to as the platinum-group elements Density ne 21.45 12.02 12.41 22.65 12.45 22.61 19.3 (gcm-3) mi (PGE). The other PGE are palladium (Pd), iridium (Ir), osmium e Melting bl (Os), rhodium (Rh) and ruthenium (Ru). Reference is also 1769 1554 1960 2443 2310 3050 1064 na point (ºC) ai commonly made to platinum-group metals and to platinum- Electrical st group minerals, both often abbreviated to PGM. In this su resistivity r document we use PGM to refer to platinum-group minerals. 9.85 9.93 4.33 4.71 6.8 8.12 2.15 f o (micro-ohm re cm at 0º C) nt Chemically the PGE are all very similar, but their physical Hardness Ce Minerals 4-4.5 4.75 5.5 6.5 6.5 7 2.5-3 properties vary considerably (Table 1). Platinum, iridium (Mohs) and osmium are the densest known metals, being significantly denser than gold. Platinum and palladium are Table 1 Selected properties of the six platinum-group highly resistant to heat and to corrosion, and are soft and elements (PGE) compared with gold (Au). ductile. Rhodium and iridium are more difficult to work, while ruthenium and osmium are hard, brittle and almost pentlandite, or in PGE-bearing accessory minerals (PGM). -

Chapter 9 Gold-Rich Porphyry Deposits: Descriptive and Genetic Models and Their Role in Exploration and Discovery

SEG Reviews Vol. 13, 2000, p. 315–345 Chapter 9 Gold-Rich Porphyry Deposits: Descriptive and Genetic Models and Their Role in Exploration and Discovery RICHARD H. SILLITOE 27 West Hill Park, Highgate Village, London N6 6ND, England Abstract Gold-rich porphyry deposits worldwide conform well to a generalized descriptive model. This model incorporates six main facies of hydrothermal alteration and mineralization, which are zoned upward and outward with respect to composite porphyry stocks of cylindrical form atop much larger parent plutons. This intrusive environment and its overlying advanced argillic lithocap span roughly 4 km vertically, an interval over which profound changes in the style and mineralogy of gold and associated copper miner- alization are observed. The model predicts a number of geologic attributes to be expected in association with superior gold-rich porphyry deposits. Most features of the descriptive model are adequately ex- plained by a genetic model that has developed progressively over the last century. This model is domi- nated by the consequences of the release and focused ascent of metalliferous fluid resulting from crys- tallization of the parent pluton. Within the porphyry system, gold- and copper-bearing brine and acidic volatiles interact in a complex manner with the stock, its wall rocks, and ambient meteoric and connate fluids. Although several processes involved in the evolution of gold-rich porphyry deposits remain to be fully clarified, the fundamental issues have been resolved to the satisfaction of most investigators. Explo- ration for gold-rich porphyry deposits worldwide involves geologic, geochemical, and geophysical work but generally employs the descriptive model in an unsophisticated manner and the genetic model hardly at all. -

STREAK Streak Means the Color of a Mineral in Its Powdered Form. The

STREAK Streak means the color of a mineral in its powdered form. The name comes from the common method of observing it by scraping the mineral on a tile of white, unglazed porcelain to produce a narrow streak of powder. Streak is a valuable property because its color is usually the same even when larger samples of many minerals show a variety of colors. Streak is often better for mineral identification than color. Streak of metallic minerals Streak is valuable for identification of many metallic minerals, including native metals (such as gold), oxides and sulfide. Almost all of these minerals have metallic or submetallic luster and are opaque. Their streak is often quite different from their color in a hand sample, generally darker. Examples: Hematite: Hematite can occur as black crystals, steel gray in the form known as specularite, and as dull red earthy masses. Its streak, however, is always blood red. By this simple test hematite can be known apart from other black, metallic minerals of similar appearance. Pyrite: Pyrite comes in a brassy yellow color, but has a black or greenish-black streak. It is sometimes called “fool’s gold” because people mistook specks in ores for real gold. But native gold has a gold streak. Chalcopyrite and marcasite are closely related to pyrite. They have paler brassy colors than pyrite, but also show dark streaks. Bornite: Bornite is bronze color when fresh, but quickly tarnishes to blue and purple shades, and eventually turns black. Its streak, however, is always grayish black. Streak of nonmetallic minerals In contrast, most minerals with nonmetallic lusters are transparent or translucent, and have a streak paler than their color in hand-samples. -

STRATIFORM and ALLUVIAL Plafl NUM MINERALIZATION in THE

LU3 The Canadian M iner alog is t Vol. 33,pp. 1023-lM5(1995) STRATIFORMAND ALLUVIALPLAfl NUM MINERALIZATION IN THENEW CALEDONIA OPHIOLITE COMPLEX THIERRY AUGE lNI PIERREMATIRZOT BRGM'Metallogeny and Geotynarnics", B.P. 6009, 45060 Orldans Cedex 2, France ABSTRA T An unusualtype offt mineralizationhas beenfound in the New Caledoniaophiolite complex, associatedwitl stratiform chromite-bearingrocks at the baseof the cumulateseries (close to the transition zone betweendunite and pyroxene-bearing rocks) and with cbromite-richpyroxenite dykes from the samezone. Two placer deposis, both enrichedin Fl also have been recognized one derived from the chromite-rich horizons and the other a cbromitiferous beach sand of unknown origin. Chromite-bearingrocks aremarked by a very strongenrichment in Pt relative to fhe other platinum-groupelements (PGE), $'ith a rrardmunconcentration of 11.5ppm (average3.9 ppm). The Pt enrichmenttakes the form of platinum-groupminerals (PGM) included in chromite crystals and is interpretedas being pdlrar'/. The following minerals have been identified: ft-Fe{u alloys (isoferroplatinum,tulame€nite, tetraferroplatinum and undeterminedphases), cooperite, laurite, bowieite, malanite, cuprorhodsite,unnamed PGE oxides, and base-metalsulfides with PGE in solid solution. The associatedplacers show a slightly different mineral association,with isoferroplatinum,tulameenite, and rare cooperite,sperrylite, Os-k-Ru alloys and PGE oxides. A more complex paragenesishas been identified in the beach san4 with isoferroplatinum,cooperite, laurite, erlichmanite, Os-Ir-Ru alloys, bowieite, ba$ite, hollingworthire, sperrylite, stibiopalladinite, and unnamed Rh sulfide, Pt-Ru-Rh alloy and PGE oxides. This type of mineralization, which differs markedly from the Os-Ru-h mineralization previously recognized in podiform cbromitite in New Caledonia, shows several analogies with Alaskan-type PGE mineralization.The host chromitite,with typical cumulustextwes, is markedby Ti and Feh emichmentdue to derivationfrom an evolved liquid. -

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg

ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE HUGH ALLSOPP LABORATORY University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX- PROCESS OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT J.A. KINNAIRD, F.J. KRUGER, P.A.M. NEX and R.G. CAWTHORN INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND JOHANNESBURG CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT by J. A. KINNAIRD, F. J. KRUGER, P.A. M. NEX AND R.G. CAWTHORN (Department of Geology, School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, P.O. WITS 2050, Johannesburg, South Africa) ECONOMIC GEOLOGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE INFORMATION CIRCULAR No. 369 December, 2002 CHROMITITES OF THE BUSHVELD COMPLEX – PROCESSES OF FORMATION AND PGE ENRICHMENT ABSTRACT The mafic layered suite of the 2.05 Ga old Bushveld Complex hosts a number of substantial PGE-bearing chromitite layers, including the UG2, within the Critical Zone, together with thin chromitite stringers of the platinum-bearing Merensky Reef. Until 1982, only the Merensky Reef was mined for platinum although it has long been known that chromitites also host platinum group minerals. Three groups of chromitites occur: a Lower Group of up to seven major layers hosted in feldspathic pyroxenite; a Middle Group with four layers hosted by feldspathic pyroxenite or norite; and an Upper Group usually of two chromitite packages, hosted in pyroxenite, norite or anorthosite. There is a systematic chemical variation from bottom to top chromitite layers, in terms of Cr : Fe ratios and the abundance and proportion of PGE’s. Although all the chromitites are enriched in PGE’s relative to the host rocks, the Upper Group 2 layer (UG2) shows the highest concentration. -

Geological Investigations in the Bird River Sill, Southeastern Manitoba (Part of NTS 52L5): Geology and Preliminary Geochemical Results by C.A

GS-19 Geological investigations in the Bird River Sill, southeastern Manitoba (part of NTS 52L5): geology and preliminary geochemical results by C.A. Mealin1 Mealin, C.A. 2006: Geological investigations in the Bird River Sill, southeastern Manitoba (part of NTS 52L5): geology and preliminary geochemical results; in Report of Activities 2006, Manitoba Science, Technology, Energy and Mines, Manitoba Geological Survey, p. 214–225. Summary and gravitational differentiation. In 2005, this study was initiated to examine the Bird Theyer (1985) identified unusual River Sill (BRS), a mafic-ultramafic layered intrusion cooling conditions requiring several magma pulses and located in the Bird River greenstone belt in southeastern cast doubt on a single magmatic intrusion theory. Manitoba. The BRS is currently an exploration target In 2005, this study was initiated to examine the for Ni-Cu–platinum group element (PGE) deposits and, controls on Ni-Cu-PGE mineralization and test the single in the past, hosted two Ni-Cu mines (Maskwa West and versus multiple injection hypothesis to establish the Dumbarton mines). relationship between mineralization and the magmatic Nickel-copper mineralization on the western half history. Specific objectives include of the BRS consists primarily of disseminated to blebby • detailed mapping of the Chrome, Page, Peterson pyrrhotite+chalcopyrite and is present in the ultramafic Block and National-Ledin properties (Figure GS-19-1); series of the Chrome and Page properties and the mafic • determination of the sulphur source for the Ni-Cu- series of the Wards property. During this study, several PGE mineralization; new sulphide-bearing localities in both the ultramafic and • delineation of the sill’s sulphur saturation history; mafic units of the sill have been identified. -

Chapter 3 Nonsilicate Minerals the 8 Most Common Elements in the Continental Crust Elements That Comprise Most Minerals Classification of Minerals

Chapter 3 Nonsilicate Minerals The 8 Most Common Elements in the Continental Crust Elements That Comprise Most Minerals Classification of Minerals ! "Important nonsilicate minerals •" Several major groups exist including –"Oxides –"Sulfides –"Sulfates –"Native Elements –"Carbonates –"Halides –"Phosphates Classification of Minerals ! "Important nonsilicate minerals •" Many nonsilicate minerals have economic value •" Examples –"Hematite (oxide mined for iron ore) –"Halite (halide mined for salt) –"Sphalerite (sulfide mined for zinc ore) –"Native Copper (native element mined for copper) Table 3.2 (Modified) Common Nonsilicate Mineral Groups Classification of Minerals ! "Important nonsilicate minerals •" Oxides – natural compounds in which Oxygen anions combine w/ a variety of metal cations –"Ores of various metals –"Hematite & Magnetite (iron oxides), Chromite (iron-chromium oxide), Ilmenite (iron-titanium oxide) and Ice (H2O – the solid form of water) are some important oxides Hematite (Fe2O3) Ore of Iron Red Streak Metallic to Earthy Luster Black or Red Color Magnetite (Fe3O4) Ore of Iron Strong Magnetism Black Color Hardness (6) Metallic Luster Corundum (Ruby& Sapphire) (Al2O3) Gemstone Hardness = 9 (Scratches Knife), Hexagonal Crystals, Adamantine Luster, Color Variable, But Can Be Red (Ruby) or Blue (Sapphire) Chromite (FeCr2O4) Ore of Chromium Metallic to Submetallic Luster Iron Black to Brownish Black Color Octahedral Crystal Form Hardness (5.5-6) Ilmenite (FeTiO3) Ore of Titanium Black-Brownish Black Streak Metallic to Submetallic -

High-Temperature Thermomagnetic Properties of Vivianite Nodules

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Discussions Open Access Open Access Biogeosciences Biogeosciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Clim. Past, 9, 433–446, 2013 Climate www.clim-past.net/9/433/2013/ Climate doi:10.5194/cp-9-433-2013 of the Past of the Past © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Discussions Open Access Open Access Earth System Earth System Dynamics Dynamics Discussions High-temperature thermomagnetic properties of Open Access Open Access vivianite nodules, Lake El’gygytgyn, Northeast RussiaGeoscientific Geoscientific Instrumentation Instrumentation P. S. Minyuk1, T. V. Subbotnikova1, L. L. Brown2, and K. J. Murdock2 Methods and Methods and 1North-East Interdisciplinary Scientific Research Institute, Far East Branch of the Russian AcademyData Systems of Sciences, Data Systems Magadan, Russia Discussions Open Access 2 Open Access Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA Geoscientific Geoscientific Correspondence to: P. S. Minyuk ([email protected]) Model Development Model Development Received: 7 September 2012 – Published in Clim. Past Discuss.: 9 October 2012 Discussions Revised: 15 January 2013 – Accepted: 15 January 2013 – Published: 19 February 2013 Open Access Open Access Hydrology and Hydrology and Abstract. Vivianite, a hydrated iron phosphate, is abun- 1 Introduction Earth System Earth System dant in sediments of Lake El’gygytgyn, located in the Anadyr Mountains of central Chukotka, northeastern Rus- Sciences Sciences sia (67◦300 N, 172◦050 E). -

Mineral Identification

Mineral Identification Let’s identify some minerals! What do good scientists do? GOOD SCIENTISTS… ⚫ work together and share their information. ⚫ observe carefully. ⚫ record their observations. ⚫ learn from their observations and continue to test, examine, and discuss. What are minerals? MINERALS ARE… ⚫ matter. ⚫ inorganic (nonliving) solids found in nature. ⚫ made up of elements such as silicon, oxygen, carbon, iron. ( Si O C Fe) ⚫ NOT ROCKS!! Rocks are made up of minerals. Physical Properties ⚫ What are physical properties of matter? ⚫ Shape, color, texture, size, etc. ⚫ The physical properties of minerals are… ⚫Transparency ⚫Luster ⚫Fracture ⚫COLOR ⚫Cleavage ⚫STREAK ⚫Specific Gravity ⚫Crystal Form ⚫HARDNESS Physical Properties ⚫ Some physical properties of minerals we won’t be examining in this lab: How well light passes ⚫Transparency through ⚫ Fracture/Cleavage How it breaks ⚫ Crystal Form The pattern of its crystal formation Color Some minerals are easy to identify by color. ⚫ Malachite is always green. But the color of other minerals change when there are traces of other elements. ⚫ Quartz is clear in its purest form. ⚫ With traces of iron, it becomes purple…amethyst. ⚫ With traces of manganese, it become pink…rose quartz. Takeaway: Visual color helps in identification. Because visual color can be affected by traces of elements, scientists use another test, of streak color. Streak ⚫ Rubbing a mineral firmly across an unglazed porcelain tile (streak plate) leaves a line of powder. ⚫ The streak color of a mineral is always the same, regardless of its visual color. ⚫ For instance, both amethyst and rose quartz leave the white streak of quartz in its purest form. Takeaway: Streak color is an even more reliable way to identify a mineral. -

The Mineralogy and Crystallography of Pyrrhotite

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION ________________________________________________________ 1.1 Introduction Pyrrhotite Fe(1-x)S is one of the most commonly occurring metal sulfide minerals and is recognised in a variety of ore deposits including nickel-copper, lead-zinc, and platinum group element (PGE). Since the principal nickel ore mineral, pentlandite, almost ubiquitously occurs coexisting with pyrrhotite, the understanding of the behaviour of pyrrhotite during flotation is of fundamental interest. For many nickel processing operations, pyrrhotite is rejected to the tailings in order to control circuit throughput and concentrate grade and thereby reduce excess sulfur dioxide smelter emissions (e.g. Sudbury; Wells et al., 1997). However, for platinum group element processing operations, pyrrhotite recovery is targeted due to its association with the platinum group elements and minerals (e.g. Merensky Reef; Penberthy and Merkle, 1999; Ballhaus and Sylvester, 2000). Therefore, the ability to be able to manipulate pyrrhotite performance in flotation is of great importance. It can be best achieved if the mineralogical characteristics of the pyrrhotite being processed can be measured and the relationship between mineralogy and flotation performance is understood. The pyrrhotite mineral group is non-stoichiometric and has the generic formula of Fe(1-x)S where 0 ≤ x < 0.125. Pyrrhotite is based on the nickeline (NiAs) structure and is comprised of several superstructures owing to the presence and ordering of vacancies within its structure. Numerous pyrrhotite superstructures have been recognised in the literature, but only three of them are naturally occurring at ambient conditions (Posfai et al., 2000; Fleet, 2006). This includes the stoichiometric FeS known as troilite which is generally found in extraterrestrial localities, but on occasion, has also been recognised in some nickel deposits (e.g. -

Using the High-Temperature Phase Transition of Iron Sulfide Minerals As

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Using the high-temperature phase transition of iron sulfde minerals as an indicator of fault Received: 9 November 2018 Accepted: 15 May 2019 slip temperature Published: xx xx xxxx Yan-Hong Chen1, Yen-Hua Chen1, Wen-Dung Hsu2, Yin-Chia Chang2, Hwo-Shuenn Sheu3, Jey-Jau Lee3 & Shih-Kang Lin2 The transformation of pyrite into pyrrhotite above 500 °C was observed in the Chelungpu fault zone, which formed as a result of the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake in Taiwan. Similarly, pyrite transformation to pyrrhotite at approximately 640 °C was observed during the Tohoku earthquake in Japan. In this study, we investigated the high-temperature phase-transition of iron sulfde minerals (greigite) under anaerobic conditions. We simulated mineral phase transformations during fault movement with the aim of determining the temperature of fault slip. The techniques used in this study included thermogravimetry and diferential thermal analysis (TG/DTA) and in situ X-ray difraction (XRD). We found diversifcation between 520 °C and 630 °C in the TG/DTA curves that signifes the transformation of pyrite into pyrrhotite. Furthermore, the in situ XRD results confrmed the sequence in which greigite underwent phase transitions to gradually transform into pyrite and pyrrhotite at approximately 320 °C. Greigite completely changed into pyrite and pyrrhotite at 450 °C. Finally, pyrite was completely transformed into pyrrhotite at 580 °C. Our results reveal the temperature and sequence in which the phase transitions of greigite occur, and indicate that this may be used to constrain the temperature of fault-slip. This conclusion is supported by feld observations made following the Tohoku and Chi-Chi earthquakes.