The Oxygen of Amplification Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(MAID) on the Hinge Dating Application

Hackerone Bug Bounty Report: Modification of Assumed Immutable Data (M.A.I.D) on the Hinge Dating Application Abusing default settings in the Cloudinary Image Transformation API Tyler Butler Testing Approach The general approach to the security analysis conducted Figure 1: Bug Bounty Details in this report involved two main steps. First, Burpsuite Platform HackerOne was used to intercept network traffic sent between a Client Hinge sample iPhone and the Hinge HTTP and HTTPS API Title Profile Photo URL Manipulation Enables Modification endpoints. Burpsuite is an application security testing of Assumed-Immutable Data software produced by Portswigger. Intercepted traffic Severity Low (3.7) was dissected by endpoint, and manually analyzed. Weakness Modification of Assumed-Immutable Data (MAID) Second, the application was used on an iPhone as a Bounty $250 normal user. Features which exposed endpoints were tested and all external links were collected and analyzed. To protect Hinge user’s personal information, exploit Abstract POC documentation included in this report uses sample Hinge is dating application for android and iOS devices Cloudinary assets not associated with Hinge. launched in 2013. Like its competitors Tinder and Bumble, it enables users to search through a database of other users and match with potential dating partners. Application Design Offering features to create unique profiles, integrate with The Hinge platform consists of native applications for existing social platforms, and chat with other users, it both android and iOS devices. In addition to integration uses a mixture of proprietary code and third-party with the Facebook-owned social media platform services. This report outlines a low risk misconfiguration Instagram, there are also several third-party Software as disclosed to Hinge through Hackerone in March of 2020 a Service (SaaS) providers used to supplement custom by Tyler Butler and triaged in June 2020. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

Marketing Planning Guide for Professional Services Firms Copyright © 2013

The Hinge Research Institute MarketingMarketing PlanningPlanning GuideGuide SECOND EDITION FOR PROFESSIONAL SERVICES Marketing Planning Guide for Professional Services Firms Copyright © 2013 Published by Hinge 1851 Alexander Bell Drive Suite 350 Reston, Virginia 20191 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Design by Hinge. Visit our website at www.hingemarketing.com Marketing Planning Guide for Professional Services Firms Table of Contents 6 Chapter 1: Marketing Then and Now Offline Marketing Online Marketing Best of Breed Marketing 8 Chapter 2: Which Way Do I Grow? - Deciding Direction SWOT Analysis 11 Chapter 3: Look Both Ways - The Value of External Research Types of Research 13 Chapter 4: Message in a Bottle - Creating a Clear Message Messaging as an Action 16 Chapter 5: “X” Marks the Spot - Making the Marketing Plan Think Long - Term: Act Short-Term How to Monitor Your Plan Sample Marketing Ledger Think Agile When To Start Planning Who Should Be Involved? Marketing Planning Guide for Professional Services Firms Table of Contents contd. 23 Chapter 6: Updating A Traditional Marketing Plan Advertising Networking Speaking Partnerships Training Public Relations 27 Chapter 7: Turbo-Charging Your Online Plan Invest in Your Website Manage Your Content Grow Your Email List Embrace Lead Generation Make Time 31 Chapter 8: Life in the Lead Stay Current Buying Trends Spending Growth 36 Chapter 9: Conclusion 37 About Hinge Marketing Planning Guide for Professional Services Firms Introduction If you are a professional services executive, there is a good chance that you’ve been involved in the marketing planning process. -

Neural Systems of Visual Attention Responding to Emotional Gestures

Neural systems of visual attention responding to emotional gestures Tobias Flaisch a,⁎, Harald T. Schupp a, Britta Renner a, Markus Junghöfer b a Department of Psychology, University of Konstanz, P.O. Box D 36, 78457 Konstanz, Germany b Institute for Biomagnetism and Biosignalanalysis, Münster University Hospital, Malmedyweg 1, 48149 Münster, Germany abstract Humans are the only species known to use symbolic gestures for communication. This affords a unique medium for nonverbal emotional communication with a distinct theoretical status compared to facial expressions and other biologically evolved nonverbal emotion signals. While a frown is a frown all around the world, the relation of emotional gestures to their referents is arbitrary and varies from culture to culture. The present studies examined whether such culturally based emotion displays guide visual attention processes. In two experiments, participants passively viewed symbolic hand gestures with positive, negative and neutral emotional meaning. In Experiment 1, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measurements showed that gestures of insult and approval enhance activity in selected bilateral visual associative brain regions devoted to object perception. In Experiment 2, dense sensor event related brain potential recordings (ERP) revealed that emotional hand gestures are differentially processed already 150 ms poststimulus. Thus, the present studies provide converging neuroscientific evidence that emotional gestures provoke the cardinal signatures of selective visual attention regarding brain structures and temporal dynamics previously shown for emotional face and body expressions. It is concluded that emotionally charged gestures are efficient in shaping selective attention processes already at the level of stimulus perception. Introduction their referents is arbitrary, builds upon shared meaning and convention, and consequently varies from culture to culture (Archer, In natural environments, emotional cues guide visual attention 1997). -

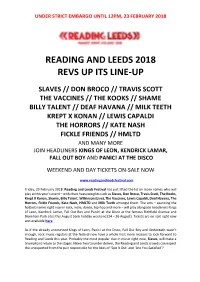

Reading and Leeds 2018 Revs up Its Line-Up

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 READING AND LEEDS 2018 REVS UP ITS LINE-UP SLAVES // DON BROCO // TRAVIS SCOTT THE VACCINES // THE KOOKS // SHAME BILLY TALENT // DEAF HAVANA // MILK TEETH KREPT X KONAN // LEWIS CAPALDI THE HORRORS // KATE NASH FICKLE FRIENDS // HMLTD AND MANY MORE JOIN HEADLINERS KINGS OF LEON, KENDRICK LAMAR, FALL OUT BOY AND PANIC! AT THE DISCO WEEKEND AND DAY TICKETS ON-SALE NOW www.readingandleedsfestival.com Friday, 23 February 2018: Reading and Leeds Festival has just lifted the lid on more names who will play at this year’s event – with chart heavyweights such as Slaves, Don Broco, Travis Scott, The Kooks, Krept X Konan, Shame, Billy Talent, Wilkinson (Live), The Vaccines, Lewis Capaldi, Deaf Havana, The Horrors, Fickle Friends, Kate Nash, HMLTD and Milk Teeth amongst them. The acts – spanning the hottest names right now in rock, indie, dance, hip-hop and more – will play alongside headliners Kings of Leon, Kendrick Lamar, Fall Out Boy and Panic! at the Disco at the famous Richfield Avenue and Bramham Park sites this August bank holiday weekend (24 – 26 August). Tickets are on-sale right now and available here. As if the already announced Kings of Leon, Panic! at the Disco, Fall Out Boy and Underøath wasn’t enough, rock music regulars at the festival now have a whole host more reasons to look forward to Reading and Leeds this year. Probably the most popular duo in music right now, Slaves, will make a triumphant return to the stages. Never two to under deliver, the Reading and Leeds crowds can expect the unexpected from the pair responsible for the likes of ‘Spit It Out’ and ‘Are You Satisfied’? UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 12PM, 23 FEBRUARY 2018 With another top 10 album, ‘Technology’, under their belt, Don Broco will be joining the fray this year. -

The Definitive Guide to the Most Influential People in the Online Dating Industry

WWW.GLOBaldatinginsights.COM POWER BOOK 2017 THE DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO THE MOST INFLUENTIAL PEOPLE IN THE ONLINE DATING INDUSTRY 2017 Sponsor 1 INTRODUCTION Welcome to the GDI Power Book 2017, the This year’s Power Book recognises the third time Global Dating Insights has named biggest players in the market who are truly the most influential and powerful people in driving, shaping and defining our industry. the online dating industry. For this report, we will be placing a The past 12 months have been a real special focus on the events of the past 12 rollercoaster for the online dating industry. months, looking at the leaders and A tough industry that is getting more companies who have influenced the industry competitive, incumbents continue to feel the during this period. pressure of a new landscape as startups It is the work and dedication of these struggle to monetise and stay afloat, while the talented people that continues to shape the gap at the top grows. world of online dating for millions of singles There has been some big market across the globe. consolidation with MeetMe buying Skout for In association with Dating Factory, $55m, and DateTix, Paktor and if(we) all we are proud to present the GDI Power making acquisitions in the past 12 months. Book 2017. We’ve also seen the market move into new areas - Tinder stepping into group dating and onto Apple TV, Bumble and Hinge following Snapchat’s lead with story- SIMON CORBETT based profiles, as Momo and Paktor search FOUNDER, for growth beyond the dating space. -

A CAMPAIGN to DEFRAUD President Trump’S Apparent Campaign Finance Crimes, Cover-Up, and Conspiracy

A CAMPAIGN TO DEFRAUD President Trump’s Apparent Campaign Finance Crimes, Cover-up, and Conspiracy Noah Bookbinder, Conor Shaw, and Gabe Lezra Noah Bookbinder is the Executive Director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW). Previously, Noah has served as Chief Counsel for Criminal Justice for the United States Senate Judiciary Committee and as a corruption prosecutor in the United States Department of Justice’s Public Integrity Section. Conor Shaw and Gabe Lezra are Counsel at CREW. The authors would like to thank Adam Rappaport, Jennifer Ahearn, Stuart McPhail, Eli Lee, Robert Maguire, Ben Chang, and Lilia Kavarian for their contributions to this report. citizensforethics.org · 1101 K St NW, Suite 201, Washington, DC 20005 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. 5 TABLE OF POTENTIAL CRIMINAL OFFENSES .............................................................................. 7 I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................... 8 A. Trump’s familiarity with federal laws regulating campaign contributions ...........................................8 B. Trump, Cohen, and Pecker’s hush money scheme.................................................................................... 10 C. AMI’s -

Alumni News Spring 2019

ALUMNI UPDATE St. Dominic School Spring, 2019 Peter & Rita Carfagna Class of 1967 Faith and Family First While both Peter Carfagna and Rita Murphy Carfagna are successful St. Dominic School alumni in many arenas, it is their love of family and faith that inspires. Together, they are the majority owners of the Lake County Captains baseball team. Rita is a Beaumont and St. Mary’s College graduate. While raising her family, she stayed connected to her parish by volunteering as a PSR teacher at St. Calling all SDS Alumni! Dominic. She has served on a multitude of boards including We'd love to share your story the Jesuit Retreat House, the Murphy Family Foundation, with the St. Dominic and America Magazine. community. Find us on: Peter Carfagna, her husband of 42 years is a graduate of St. @stdominicschool Ignatius High School, Harvard, and Harvard Law School. He is an attorney who specializes in sports law and has been a partner at Jones Day and Chief Legal Officer for @StDomShaker International Management Group. He is currently teaching sports law at Harvard in the fall and winter terms. stdomshaker This impressive couple met in first grade at St. Dominic School and maintained their friendship through high school and college. Their parents, Jerry and Margaret Murphy and Peter and Jeanne Carfagna, were founding members of the parish. The Carfagnas remained friends with many of their SDS classmates (including Dominic and Gaile Ozanne) and St. Dominic School just recently celebrated their 50th class reunion. "Tomorrow's Some of their favorite St. Dominic memories include, Leaders Start “attending the daily Masses as a whole school, especially the May Crowning of Mary when all of the students of the Here" school formed a human rosary around the inside of the church; dressing up as our favorite saints for the All Saints Day Mass; the annual St. -

Punching Tools

TruServices Punching Tools Order easily – with the correct specifica- tions for the right tool. Have you thought of everything? Machine type Machine number Tool type Dimensions or drawings in a conventional CAD format (e.g. DXF) Sheet thickness Material Quantity Desired delivery date Important ordering specifications ! Please observe the "Important ordering specifications" on each product page as well. Order your punching tools securely and conveniently 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in our E-Shop at: www.trumpf.com/mytrumpf Alternatively, practical inquiry and order forms are available to you in the chapter "Order forms". TRUMPF Werkzeugmaschinen GmbH + Co. KG International Sales Punching Tools Hermann-Dreher-Strasse 20 70839 Gerlingen Germany E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.trumpf.com Content Order easily – with the correct specifica- General information tions for the right tool. TRUMPF System All-round Service Industry 4.0 MyTRUMPF 4 Have you thought of everything? Machine type Punching Machine number Classic System MultiTool Tool type Cluster tools MultiUse Dimensions or drawings in a conventional CAD format (e.g. DXF) 12 Sheet thickness Material Cutting Quantity Slitting tool Film slitting tool Desired delivery date MultiShear 44 Important ordering specifications ! Please observe the "Important ordering specifications" on each product page as well. Forming Countersink tool Thread forming tool Extrusion tool Cup tool 58 Marking Order your punching tools securely and conveniently 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in our E-Shop at: Center punch tool Marking tool Engraving tool Embossing tool www.trumpf.com/mytrumpf 100 Alternatively, practical inquiry and order forms are available to you in the chapter "Order forms". -

Canvas 06 Music.Pdf

THE MUSIC ISSUE ALTER I think I have a pretty cool job as and design, but we’ve bridged the editor of an online magazine but gap between the two by including PAGE 3 if I could choose my dream job some of our favourite bands and I’d be in a band. Can’t sing, can’t artists who are both musical and play any musical instrument, bar fashionable and creative. some basic work with a recorder, but it’s still a (pipe) dream of mine We have been very lucky to again DID I STEP ON YOUR TRUMPET? to be a front woman of some sort work with Nick Blair and Jason of pop/rock/indie group. Music is Henley for our editorials, and PAGE 7 important to me. Some of my best welcome contributing writer memories have been guided by a Seema Duggal to the Canvas song, a band, a concert. I team. I met my husband at Livid SHAKE THAT DEVIL Festival while watching Har Mar CATHERINE MCPHEE Superstar. We were recently EDITOR PAGE 13 married and are spending our honeymoon at the Meredith Music Festival. So it’s no surprise that sooner or later we put together a MUSIC issue for Canvas. THE HORRORS This issue’s theme is kind of a departure for us, considering we PAGE 21 tend to concentrate on fashion MISS FITZ PAGE 23 UNCOVERED PAGE 28 CREATIVE DIRECTOR/FOUNDER CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS Catherine McPhee NICK BLAIR JASON HENLEY DESIGNER James Johnston COVER COPYRIGHT & DISCLAIMER EDITORIAL MANAGER PHOTOGRAPHY Nick Blair Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission by Canvas is strictly prohibited. -

Improving Communication Based on Cultural

IMPROVING COMMUNICATION BASED ON CULTURAL COMPETENCY IN THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT by Walter N. Burton III A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2011 IMPROVING COMMUNICATION BASED ON CULTURAL COMPETENCY IN THE BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT by Walter N. Burton III This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Patricia Darlington, School of Communication and Multimedia Studies, and has been approved by the members ofhis supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ~o--b Patricia Darlington, Ph.D. ~.:J~~ Nannetta Durnell-Uwechue, Ph.D. ~~C-~ Arthur S. E ans, J. Ph.D. c~~~Q,IL---_ Emily~ard, Ph.D. Director, Comparative Studies Program ~~~ M~,Ph.D. Dean, The Dorothy F. Schmidt College ofArts & Letters ~~~~ Dean, Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the members of my committee Prof. Patricia Darlington, Prof. Nennetta Durnell-Uwechue, Prof. Arthur Evans, and Prof. Angela Rhone for your diligent readings of my work as well as your limitless dedication to the art of teaching. I would like to offer a special thanks to my Chair Prof. Patricia Darlington for your counsel in guiding me through this extensive and arduous project. I speak for countless students when I say that over the past eight years your inspiration, guidance, patience, and encouragement has been a constant beacon guiding my way through many perils and tribulations, along with countless achievements and accomplishments. -

18, 2015 Agenda Speakers Registration Awards

Hyatt Regency On the Riverwalk AgendaOptional WorkshopsAbout the Speakers Registration Awards Digital Media & Behavior Change 15th Annual AAHB Scientific Meeting March 15 -18, 2015 www.aahb.org Hyatt Regency on the Riverwalk — San Antonio, Texas Digital Media & Behavior Change Join fellow The 15th Annual Academy meeting will provide a forum for researchers to health behavior learn about the increasing importance of participatory, open and collaborative approaches to research that can be supported by emerging researchers technologies in health, behavior change, medicine & research. and scholars Sunday, March 15, 2015 as we learn, AAHB 2015 Annual Meeting Welcome network, and 12:30pm—4:30pm Optional Professional Development Workshop Pecan Room (registration required) socialize by the Analyzing and visualizing social media networks Riverwalk in with NodeXL Derek Hansen, PhD, Brigham Young University Historic School of Technology San Antonio, 12:00pm—5:00pm Registration - Rio Grande Foyer Texas! 6:30pm—7:00pm Welcome Address, Presentation of New AAHB Fellows, Rio Grande Ballroom Judy K. Black Award, Research Scholars, Membership Milestones and Changes, & New Members Dong-Chul Seo, PhD, Indiana University, AAHB President 7:00pm—7:30pm Introduction of 2015 Research Laureate David B. Abrams, PhD, 2014 Recipient 2015 AAHB Research Laureate Presentation Gary L. Kreps, PhD, 2015 Recipient 7:30pm—8:45 pm Opening Reception and Poster Session Blanco/Llano/Pecos Heavy hors d’oeuvres, 1 free drink per person and cash bar Hill Country Level (guest tickets available) 2015 Research Laureate Award Recipient Gary L. Kreps, PhD George Mason University http://www.aahb.org Monday, March 16, 2015 6:30am—7:30am Unplug Event: Functional Fitness and Mobility with Katie Heinrich, PhD Nueces 8:00 am -5:00 pm Registration - Rio Grande Foyer 7:30am-8:30 am Breakfast Roundtables: New Members, conference attendees, and students are encouraged to join a roundtable and meet senior Academy members.