Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Report on the Preliminary Feasibility Study

Field report on the Preliminary Feasibility Study On Walking Trees along Lifezone Ecotones in Barun Valley, Nepal (A pilot project to develop key indicators for monitoring Biomeridians - Climate Response through Information & Local Engagement) Report Prepared By: The East Foundation (TEF), Sankhuwasabha, Nepal and Future Generations University, Franklin, WV, USA Submitted to Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Babar Mahal, Kathmandu June 2018 1 Table of Contents Contents Page No. 1. Background ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Rationale ............................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Study Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Contextual Framework ...................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Study Area Description ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.3 Experimental Design and Data Collection Methodology ............................................................... 12 4. Study Findings .................................................................................................................................... 13 4.1 Geographic Summary -

Arboretum News Armstrong News & Featured Publications

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Arboretum News Armstrong News & Featured Publications Spring 2019 Arboretum News Georgia Southern University- Armstrong Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/armstrong-arbor-news Part of the Education Commons This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Armstrong News & Featured Publications at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arboretum News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arboretum News Issue 9 | Spring 2019 A Newsletter of the Georgia Southern University Armstrong Campus Arboretum From the Editor: Arboretum News, published by the Grounds Operations Department ’d like to introduce you to the Armstrong Arboretum of the new of Georgia Southern University- IGeorgia Southern University-Armstrong Campus. Designated Armstrong Campus, is distributed as an on-campus arboretum in 2001 by former Armstrong to faculty, staff, students and Atlantic State University president Dr. Thomas Jones, the friends of the Armstrong Arboretum. The Arboretum university recognized the rich diversity of plant life on campus. encompasses Armstrong’s 268- The Arboretum continues to add to that diversity and strives to acre campus and displays a wide function as a repository for the preservation and the conservation variety of shrubs and other woody of plants from all over the world. We also hope to inspire students, plants. Developed areas of campus faculty, staff and visitors to appreciate the incredible diversity contain native and introduced species of trees and shrubs. Most that plants have to offer. -

Environmental Factors Controlling the Distribution of Forest Plants with Special Reference to Floral Mixture in the Boreo-Nemora

Environmental Factors Controlling the Distribution of Forest Plants with Special Reference to Floral Mixture in the Title Boreo-Nemoral Ecotone, Hokkaido Island Author(s) Uemura, Shigeru Environmental science, Hokkaido University : journal of the Graduate School of Environmental Science, Hokkaido Citation University, Sapporo, 15(2), 1-54 Issue Date 1993-03-25 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/37276 Type bulletin (article) File Information 15(2)_1-54.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP 1 Environ,Sci.,I'Iokl{aidoUniversity 15(2) 1-54 Dec,1992 Environmental Factors Controlling the Distribution of Forest PlaRts with Special Reference to Floral Mixture in the Boreo-Nemoral EcotoRe, Hokkaido Island Shigeru Uemura Department of Biosystem Management, Division of Environmental Conservation, Graduate School of Environmental Science, Hokkaiclo University, Sapporo 060, Japan Abstract Effects of climatic factors on the plant distribution were examined by means of direct gradient analysis, and the relationship of forest flora with Iife form and phytogeographical distribution was exaniined. Subsequently, leaf phenology of forest plants were analyzed to evaluate the adaptive signifi- cance in relation to the environments in forest understory. In the boreo-nemoral forest ecotone, Kokkaido Island, northern Japan, co-occurrence of northern and southern plants in a certain forest site is more notable in the understory than in the crown, and this dates back to the late--Quaternary period, where the decrease in temperature associated with the glacial period forced the unclerstory plants to adapt their life forms or leaf habits to snowcover and to light conditions of the interior forests, I<ey words: Direct gradient analysis; Floral mixture; Leaf phenology; Mixed forest; Phytogoegraphy; Snowcover; Understory Intoroduetion In the upper-middle latitudes of Europe, eastern Asia and eastern North America, the boreal coniferous forest formation confronts to the temperate hardwood forest formation. -

2. ACER Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 1054. 1753. 枫属 Feng Shu Trees Or Shrubs

Fl. China 11: 516–553. 2008. 2. ACER Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 1054. 1753. 枫属 feng shu Trees or shrubs. Leaves mostly simple and palmately lobed or at least palmately veined, in a few species pinnately veined and entire or toothed, or pinnately or palmately 3–5-foliolate. Inflorescence corymbiform or umbelliform, sometimes racemose or large paniculate. Sepals (4 or)5, rarely 6. Petals (4 or)5, rarely 6, seldom absent. Stamens (4 or 5 or)8(or 10 or 12); filaments distinct. Carpels 2; ovules (1 or)2 per locule. Fruit a winged schizocarp, commonly a double samara, usually 1-seeded; embryo oily or starchy, radicle elongate, cotyledons 2, green, flat or plicate; endosperm absent. 2n = 26. About 129 species: widespread in both temperate and tropical regions of N Africa, Asia, Europe, and Central and North America; 99 species (61 endemic, three introduced) in China. Acer lanceolatum Molliard (Bull. Soc. Bot. France 50: 134. 1903), described from Guangxi, is an uncertain species and is therefore not accepted here. The type specimen, in Berlin (B), has been destroyed. Up to now, no additional specimens have been found that could help clarify the application of this name. Worldwide, Japanese maples are famous for their autumn color, and there are over 400 cultivars. Also, many Chinese maple trees have beautiful autumn colors and have been cultivated widely in Chinese gardens, such as Acer buergerianum, A. davidii, A. duplicatoserratum, A. griseum, A. pictum, A. tataricum subsp. ginnala, A. triflorum, A. truncatum, and A. wilsonii. In winter, the snake-bark maples (A. davidii and its relatives) and paper-bark maple (A. -

Acer Buergerianum Plants, Adequately Moist in Summer but Well Drained in Winter Is "Trident Maple" a Pretty Small Tree Whose Grace Is Enhanced by the Key to Success

Acer buergerianum plants, adequately moist in summer but well drained in winter is "Trident Maple" A pretty small tree whose grace is enhanced by the key to success. 3m. the small three-lobed leaves. Particularly good autumn colour begins scarlet turning orange-yellow. A good hardy Maple Acer x conspicuum 'Silver Cardinal' tolerant of many less favoured sites. 4m. This Snakebark has the most incredible pink and cream variegated foliage, highlighted by the red petioles and young stems. It Acer circinatum 'Monroe' occurred as a chance seedling of A. pensylvanicum and received A plant I've lusted after for years! Shrubby habit, with deeply an Award of Merit in 1985. Our stock is directly derived from incised light green leaves (even more so than A. japonicum the original seedling in the Windsor Great Park. Unless your soil 'Aconitifolium'). Predominantly yellow autumn colours may is very good, it is safest in dappled shade. 3m. develop some orange. Worthy of a special site. 3m. Acer x conspicuum 'Silver Vein' Acer circinatum 'Pacific Fire' A hybrid between A. davidii George Forrest and A. Imagine the coral bark colour of Acer palmatum 'Sangokaku' pensylvanicum Erythrocladum found at Hilliers about 1960. It is combined with the larger leaves and more tolerant growth arguably the best of the basic snakebarks for garden suitability requirements of this species, and the result is a plant with and good colour with its rich purple and white striped winter awesome potential. Fantastic autumn colour too. bark, becoming green with maturity. 5m. Acer circinatum 'Sunglow' Acer davidii This has been on my "wanted" list ever since I first saw it Delightful small tree noted for dazzling autumn colour and photographed! Apricot coloured young growth matures to attractive white striped purple bark in winter. -

Distribution of Libriform Fibers and Presence of Spiral Thickenings in Fifteen Species of Acer

IAWA Journal, Vol. 27 (2), 2006: 173–182 DISTRIBUTION OF LIBRIFORM FIBERS AND PRESENCE OF SPIRAL THICKENINGS IN FIFTEEN SPECIES OF ACER Iris Vazquez-Cooz and Robert W. Meyer State University of New York (SUNY-ESF), College of Environmental Science and Forestry, One Forestry Drive, Baker Laboratory, Syracuse, NY 13210. U.S.A. [E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]] SUMMARY Fifteen Acer species were examined to study distribution and percentage by area of their libriform fibers. Safranin-O and astra blue dissolved in alcohol solution is an effective differential staining method to identify and localize libriform fibers. They have larger lumens than fiber tracheids, intercellular spaces, and occur in various patterns, ranging from large groups to wavy bands. In some cases they occur in radial files. The per- centage by area of libriform fibers ranges from 14 to 40%. Inconspicuous to moderately visible spiral thickenings are part of the Acer libriform fibers and fiber tracheids. Differences in stain reactions and fluorescence indicate that libriform fibers differ in lignin concentration or composition from fiber tracheids – the concentration of syringyl lignin is greater in libriform fibers. Key words: Acer, differential staining, fiber distribution, libriform fibers, fiber tracheids, maple, spiral thickening, lignification. INTRODUCTION Great efforts have been made to classify libriform fibers. In 1936, I.W. Bailey established the concept of imperforate tracheary elements in recognition of the difficulty of separat- ing libriform fibers from tracheids and fiber tracheids. The occurrence and distribution of longitudinal parenchyma in wood are well documented (Panshin & De Zeeuw 1980); however, descriptive terms for distribution of libriform fibers have not been found, such as those for longitudinal parenchyma. -

Latitudinal Gradient in Leaf Defense Traits of Woody Plants Along Japanese Archipelago

Latitudinal gradient in leaf defense traits of woody plants along Japanese archipelago 日本産樹木種における、葉防御形質の緯度傾度 Saihanna 1 General Introduction It is estimated that over the twenty million species of organisms are living on our planet, and all of these organisms adapted to their own living environment, namely niche (Hatchinson 1957). Not only the abiotic factors but biotic interaction plays a key role in the maintenance of biodiversity. Animal-plant interactions are one of the most important topic in community ecology (e.g. Morin 1999). Plants and herbivore insects have accounted for about half of the entire diversity on the earth (Strong et al., 1984). Plant-herbivore interactions are extremely complex, which should lead the tremendous diversity of both plants and herbivores (e.g. Gutierrez et al., 1984; Hay et al., 1989). Although the interaction between these two components, namely co-speciation, should account for this diversification, most of the studies so far, tend to explain this interaction only from one side of them. Plants have interacted with insect herbivores for several hundred million years, which should lead to complex defense systems against various herbivores (Fürstenberg-Hägg et al., 2013). This interaction between plants and herbivores has long proposed the opportunity for studying the mechanism of the creation and maintenance of biological diversity because of its universality and generality (Strong et al. 1984; Ali and Agrawal 2012). It is believed that the evolution of plant defense traits followed by counter-adaptations in herbivores could lead to bursts of adaptive radiation of both components (Ehrlich and Raven 1969). Understanding the coevolution of plant and insect species and macroevolution of adaptive traits has inspired biologists for some decades, yet has been challenging to study even present days (Schluter, 2000). -

Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’S Letter

Planning and planting for a better world Friends of the JC Raulston Arboretum Newsletter Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’s Letter Spring greetings from the JC Raulston Arboretum! This garden- ing season is in full swing, and the Arboretum is the place to be. Emergence is the word! Flowers and foliage are emerging every- where. We had a magnificent late winter and early spring. The Cornus mas ‘Spring Glow’ located in the paradise garden was exquisite this year. The bright yellow flowers are bright and persistent, and the Students from a Wake Tech Community College Photography Class find exfoliating bark and attractive habit plenty to photograph on a February day in the Arboretum. make it a winner. It’s no wonder that JC was so excited about this done soon. Make sure you check of themselves than is expected to seedling selection from the field out many of the special gardens in keep things moving forward. I, for nursery. We are looking to propa- the Arboretum. Our volunteer one, am thankful for each and every gate numerous plants this spring in curators are busy planting and one of them. hopes of getting it into the trade. preparing those gardens for The magnolias were looking another season. Many thanks to all Lastly, when you visit the garden I fantastic until we had three days in our volunteers who work so very would challenge you to find the a row of temperatures in the low hard in the garden. It shows! Euscaphis japonicus. We had a twenties. There was plenty of Another reminder — from April to beautiful seven-foot specimen tree damage to open flowers, but the October, on Sunday’s at 2:00 p.m. -

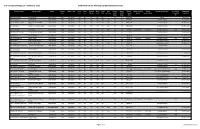

Download PCN-Acer-2017-Holdings.Pdf

PLANT COLLECTIONS NETWORK MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL ACER LIST 02/13/18 Institutional NameAccession no.Provenance* Quan Collection Id Loc.** Vouchered Plant Source Acer acuminatum Wall. ex D. Don MORRIS Acer acuminatum 1994-009 W 2 H&M 1822 1 No Quarryhill BG, Glen Ellen, CA QUARRYHILL Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 4 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 1 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 1 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 1 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.076 W 2 H&M1858 1 No Acer acuminatum 1993.076 W 1 H&M1858 1 No Acer acuminatum 1993.139 W 1 H&M1921 1 No Acer acuminatum 1993.139 W 1 H&M1921 1 No UBCBG Acer acuminatum 1994-0490 W 1 HM.1858 0 Unk Sichuan Exp., Kew BG, Howick Arb., Quarry Hill ... Acer acuminatum 1994-0490 W 1 HM.1858 0 Unk Sichuan Exp., Kew BG, Howick Arb., Quarry Hill ... Acer acuminatum 1994-0490 W 1 HM.1858 0 Unk Sichuan Exp., Kew BG, Howick Arb., Quarry Hill ... UWBG Acer acuminatum 180-59 G 1 1 Yes National BG, Glasnevin Total of taxon 18 Acer albopurpurascens Hayata IUCN Red List Status: DD ATLANTA Acer albopurpurascens 20164176 G 1 2 No Crug Farm Nursery QUARRYHILL Acer albopurpurascens 2003.088 U 1 1 No Total of taxon 2 Acer amplum (Gee selection) DAWES Acer amplum (Gee selection) D2014-0117 G 1 1 No Gee Farms, Stockbridge, MI 49285 Total of taxon 1 Acer amplum 'Gold Coin' DAWES Acer amplum 'Gold Coin' D2015-0013 G 1 2 No Gee Farms, Stockbridge, MI 49285, USA Acer amplum 'Gold Coin' D2017-0075 G 2 2 No Shinn, Edward T., Wall Township, NJ 07719-9128 Total of taxon 3 Acer argutum Maxim. -

Viscum Album L.) in Urban Areas (A Case Study of the Kaliningrad City, Russia)

plants Article Ecological and Landscape Factors Affecting the Spread of European Mistletoe (Viscum album L.) in Urban Areas (A Case Study of the Kaliningrad City, Russia) Liubov Skrypnik 1,* , Pavel Maslennikov 1 , Pavel Feduraev 1 , Artem Pungin 1 and Nikolay Belov 2 1 Institute of Living Systems, Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, Universitetskaya str., 2, Kaliningrad 236040, Russia; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (P.F.); [email protected] (A.P.) 2 Institute of Environmental Management, Urban Development and Spatial Planning, Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University, Zoologicheskaya str., 2, Kaliningrad 236022, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +74012533707 Received: 1 March 2020; Accepted: 19 March 2020; Published: 23 March 2020 Abstract: Green spaces are very important for an urban environment. Trees in cities develop under more stressful conditions and are, therefore, more susceptible to parasite including mistletoe infestation. The aim of this study was to investigate the ecological, microclimatic, and landscape factors causing the spread of European mistletoe (Viscum album L.) in urban conditions. The most numerous hosts of mistletoe were Tilia cordata (24.4%), Acer platanoides (22.7%), and Populus nigra (16.7%). On average, there were more than 10 mistletoe bushes per tree. The mass mistletoe infestations (more than 50 bushes per the tree) were detected for Populus berolinensis, Populus nigra, × and Acer saccharinum. The largest number of infected trees was detected in the green zone (city parks), historical housing estates, and green zone along water bodies. Based on the results of principal component analysis (PCA), the main factors causing the spread of mistletoe on the urban territories are trees’ age and relative air humidity. -

ABSTRACT ZENG, HAINIAN. Development

ABSTRACT ZENG, HAINIAN. Development-dependent Formation and Metabolism of Anthocyanins and Proanthocyanidins in Acer Species. (Under the direction of David Danehower, William Hoffmann, Jenny Xiang and De-yu Xie). Anthocyanins are one of the richest pigments, which belong to flavonoid compounds in plant kingdom. They have many biological and ecological functions. Over the past many years, numerous efforts have been made to determine the biosynthetic pathway of anthocyanins and also to identify several regulatory proteins mainly in flowers and fruits of model plants and crop plants. However, many questions concerning the metabolism of anthocyanins in foliage remains unsolved. One example is “How can developmental processes impact on accumulation patterns of anthocyanins in leaves”. In this study, we choose several cultivars from one of the most popular ornamental plants Acer palmatum Thunb. to understand the mechanism of developmental changes of pigmentation in leaf. Several other maple species were also analyzed. We propose that the metabolism of anthocyanins play an essential role in such changes. We use an integrated approach of phytochemistry and metabolic profiling to determine the biosynthesis and metabolism of anthocyanins and their impacts on foliage color. Proanthocyanidin analysis was carried out as well to determine their relationship to both anthocyanin production and foliar coloration. We have found that even for green leaves with no/trace amount of detectable anthocyanins, the biosynthetic pathway of anthocyanidin/proanthocyanidin -

Tree Canopy Coverage List - Deciduous Trees Snohomish County Planning and Development Services

Tree Canopy Coverage List - Deciduous Trees Snohomish County Planning and Development Services Scientific Name Common Name Family Growth Species Type Street Native Drought Moist Utility Root Mature Mature Mature Annual Growth Annual Average Growth Rate Est 20 year Longevity (if Type Tree Tree Tolerant Soil Safe Damage Height Width Canopy Height Growth Width Canopy (sq available) (feet) (feet) Area ft) Abelia grandiflora Glossy Abelia Caprifoliaceae Shrub Deciduous No No No No No 6 6 28.27431 Rapid Moderate Acer campestre Hedge Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No No Yes Low 35 25 490.87344 12 inches/season 40-150 years Acer campestre 'Evelyn' Queen Elizabeth Hedge Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No Yes No Low 50 25 490.87344 12 inches/season 40-150 years Maple Acer capillipes Japanese snakebark Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous No No No Yes No Low 35 35 962.11194 24 inches/season 40-150 years Acer circinatum Vine Maple Sapindaceae Both Deciduous No Yes No Yes No Low 25 20 314.159 12-24 inches 12 inches 24 inches/season 240 40-150 years Acer fremanii 'Scarsen' Scarlet Sentinel Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No Yes Yes No 40 20 314.159 24 inches/season 50-150 years Acer griseum Paperbark Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No Yes Yes Low 25 15 176.71444 12-24 inches/season 40-150 years Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous No Yes Yes Yes No 75 30 706.85775 36 inches 24 inches 36 inches/season 480 >150 years Acer nigrum Greencolumn Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No No No 50 20 314.159 12-24 inches/season