7 Publish Ana Martins Kay Cannon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R Kirkstall Industrial Park Carlsbad, Ca 92008 Okhla Industrial Area Ph2 Leeds Ls4 2Az New Delhi 110020 United Kingdom India

Case 2:16-bk-24862-BB Doc 535 Filed 04/06/17 Entered 04/06/17 11:59:47 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 70 1 Scott F. Gautier (State Bar No. 211742) [email protected] 2 Kevin D. Meek (State Bar No. 280562) [email protected] 3 ROBINS KAPLAN LLP 2049 Century Park East, Suite 3400 4 Los Angeles, CA 90067 Telephone: 310 552 0130 5 Facsimile: 310 229 5800 6 Attorneys for Debtor and Debtor in Possession 7 8 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 LOS ANGELES DIVISION 11 LLP AW L 12 In re: Case No. 2:16-bk-24862-BB T A 13 NG DIP INC. (f/k/a Nasty Gal Inc.), a Chapter 11 NGELES APLAN A California corporation, K OS 14 L PROOF OF SERICE RE NOTICE OF Debtor and Debtor in Possession. TTORNEYS MOTION AND MOTION FOR ENTRY OF A 15 ORDER APPROVING: (1) DISCLOSURE OBINS R 16 STATEMENT; (2) FORM AND MANNER OF NOTICE OF CONFIRMATION 17 HEARING; (3) FORM OF BALLOTS; AND (4) SOLICITATION MATERIALS AND 18 SOLICITATION PROCEDURES [DOCKET NO. 523] 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 61316050.1 1 Case 2:16-bk-24862-BB Doc 535 Filed 04/06/17 Entered 04/06/17 11:59:47 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 70 Case 2:16-bk-24862-BB Doc 535 Filed 04/06/17 Entered 04/06/17 11:59:47 Desc Main Document Page 3 of 70 NG DIP INC. (f/k/aCase Nasty 2:16-bk-24862-BB Gal Inc.), a California Corporation Doc 535 - U.S. -

Bossypants? One, Because the Name Two and a Half Men Was Already Taken

Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully thank: Kay Cannon, Richard Dean, Eric Gurian, John Riggi, and Tracy Wigfield for their eyes and ears. Dave Miner for making me do this. Reagan Arthur for teaching me how to do this. Katie Miervaldis for her dedicated service and Latvian demeanor. Tom Ceraulo for his mad computer skills. Michael Donaghy for two years of Sundays. Jeff and Alice Richmond for their constant loving encouragement and their constant loving interruption, respectively. Thank you to Lorne Michaels, Marc Graboff, and NBC for allowing us to reprint material. Contents Front Cover Image Welcome Dedication Introduction Origin Story Growing Up and Liking It All Girls Must Be Everything Delaware County Summer Showtime! That’s Don Fey Climbing Old Rag Mountain Young Men’s Christian Association The Windy City, Full of Meat My Honeymoon, or A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again Either The Secrets of Mommy’s Beauty Remembrances of Being Very Very Skinny Remembrances of Being a Little Bit Fat A Childhood Dream, Realized Peeing in Jars with Boys I Don’t Care If You Like It Amazing, Gorgeous, Not Like That Dear Internet 30 Rock: An Experiment to Confuse Your Grandparents Sarah, Oprah, and Captain Hook, or How to Succeed by Sort of Looking Like Someone There’s a Drunk Midget in My House A Celebrity’s Guide to Celebrating the Birth of Jesus Juggle This The Mother’s Prayer for Its Daughter What Turning Forty Means to Me What Should I Do with My Last Five Minutes? Acknowledgments Copyright * Or it would be the biggest understatement since Warren Buffett said, “I can pay for dinner tonight.” Or it would be the biggest understatement since Charlie Sheen said, “I’m gonna have fun this weekend.” So, you have options. -

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 112: Sophia Amoruso Show Notes and Links at Tim.Blog/Podcast

The Tim Ferriss Show Transcripts Episode 112: Sophia Amoruso Show notes and links at tim.blog/podcast Tim Ferriss: I will just do a sound check. What did you have for breakfast this morning? Sophia Amoruso: For breakfast I had a cup of coffee with two shots and heavy cream. And actually an Americano with two shots of coffee and heavy cream. And I had a smoothie with apple and yogurt and some shit in it. Tim Ferriss: Well, we will talk more about the shit part that’s going to be really very relevant. [Sponsor Ad] Tim Ferriss: Hello, my lady kittens, this is Tim Ferriss. And welcome to another episode of the Tim Ferriss Show where I attempt in each interview to deconstruct world class performers. To tease out the things you can use not just act with integrity but what does that actually mean on a daily basis. What are your morning routines, what are your habits, what are your favorite books, what are your influences, what are your favorite documentaries, so on and so forth? I really want specific tactics that you guys can apply, tool kits that you can use in your daily life and lives, that’s a plural for you guys. And this episode is no exception. I'm very excited to have Sophia Amoruso, that’s at sophia_amoruso. On the show, she is founder and Executive Chairman of Nasty Gal, which is a global online destination for both new and vintage clothing, shoes and accessories, among many other things. Founded in 2006, Nasty Gal was named fastest growing retailer in 2012, by Ink Magazine. -

Future of Work in Film and Television

Future of Work in Film and Television Panel: Careers in Comedy Television Moderator: Dani Klein Modisett ’84 Writer/Comedian, Founder "Laughter On Call" Dani Klein Modisett is a comedian/writer/actor and, most recently, the CEO and Founder of “Laughter on Call.” She is also the author of two books on the importance of laughter in family life, “Take My Spouse, Please,” and “Afterbirth…stories you won’t read in a parenting magazine.” She has written for The LA Times, NY Times, Parents Magazine, AARP and a lot of websites. She started out as an actor in NYC and did various NBC shows, a few Oliver Stone movies, and a few Broadway comedies. She taught stand-up at UCLA for undergrads and adults for 10 years and wrote and performed several comedy shows which toured colleges. After her mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, she created “Laughter On Call” which brings comedians around the country to people with dementia and runs workshops for healthcare workers and families teaching simple comedian’s tools to help break tension, create connection and, most of all, shared laughter between those who need it most. “Laughter on Call” has been featured in The Washington Post, The London Times, AARP, and on Dr. Oz and The Doctors. She has two teenage sons and is married to Tod Modisett ’94. Ayla Glass ’09 Associate Producer and Executive Assistant to Seth Green at Stoopid Buddy Stoodios, Actress Ayla Glass is a stand-up, writer, performer and producer from Kansas City (the Kansas side) and a graduate of Dartmouth College. -

PP2 SHOOTING DRAFT.Fdx

"PITCH PERFECT 2" Written by Kay Cannon Based on the book by Mickey Rapkin This material is the property of UNIVERSAL PICTURES and is intended for us only by authorized personnel. Distribution of disclosure of this material to unauthorized persons is prohibited. The sale, copying, or reproduction of this material in any form or medium, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited. As the Universal logo appears on screen, we hear Universal’s theme song being sung a cappella by... 1 INT. KENNEDY CENTER - PRESS BOX 1 Our a cappella commentators, JOHN and GAIL. JOHN Excited, Gail? GAIL If I weren’t, would I be wearing a diaper under this dress? As John speaks, we HEAR a marching band play. JOHN (V.O.) Welcome back, a cappella enthusiasts! 2 INT. KENNEDY CENTER - STAGE - AUGUST 2014 - NIGHT 2 A MILITARY BAND heads off stage as THE BARDEN BELLAS get set. JOHN I’m John Smith and sitting to my right is Gail Abernathy-McCadden- Feinberger. GAIL (pointing to wedding ring) This one’s gonna stick, John. JOHN Well you saved the Jew for last. GAIL (gleefully nodding) I did, I did. JOHN You’re listening to Let’s Talk- appella, the world’s premiere downloadable a cappella podcast. GAIL We are coming to you live from our nation’s capitol where the Barden University Bellas are about to rock the historic Kennedy Center. (CONTINUED) "Pitch Perfect 2" SHOOTING DRAFTS 5-11-14 2. 2 CONTINUED: 2 The BELLAS: BECA, CHLOE, Lilly, STACIE, CYNTHIA ROSE, JESSICA, ASHLEY and a small Latina girl, FLORENCIA FUENTES (FLO). -

Reimagining Creativity for the 21St Century!

Reimagining Creativity for the 21st Century! CTSA Website | Art | Dance | Drama | Music | UAG | Beall Center | Arts Outreach Letter from the Dean The incredible shower of arts events the Trevor School presented in April continues in full flower in May. A glance at the CTSA calendar will give you entrance to the cornucopia of information about what we’re doing—but remember that in addition to the event calendar, dozens of music recitals will also be going on: there won’t be a single day without an arts event from now ‘til the end of the term. Master classes and residencies by international musicians, the Honors Music Concert, the Music Showcase Concert, jazz, classical, dance, drama, art exhibitions—it’s all happening daily. A couple of highlights: Drama will present two very important productions: Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People in the Little Theatre and a staged concert of Evita in the Irvine Barclay Theatre. and as it always does, the UCI Symphony will conclude the academic year with a wonderful year-end concert in the Barclay. On the faculty and alumni front: 2015-16 Season! Art department: - photographer Connie Samaras has two exhibitions opening at UC San Diego - Simon Leung and Rhea Anastas will be part of the conversation series at the View our entire UCLA Hammer Museum Season Brochure. - Ulysses Jenkins will appear at Bing in Chicago - Alum Alison O’Daniel has a solo exhibition at the Knockdown Center - Katie Shapiro is in Lens/Catch, the Fine Art Photography Daily Dance: - faculty member and composer Alan Terricciano will offer -

Testing the Waters

BRINKLEY STRETCHING OUT FARFETCH OPENS ON BEAUTY AN OFFICE CHRISTIE BRINKLEY IN TOKYO AS UNVEILS A NEW SKIN CARE THE RETAILER NETWORK LINE AND TALKS ABOUT CONTINUES TO HER 40 YEARS IN THE ADD COUNTRIES SOPHIA’S SPACE FASHION AND BEAUTY AND STORES. NASTY GAL FOUNDER SOPHIA AMORUSO OPENS THE WORLDS. PAGE 8 PAGE 9 BRAND’S FIRST BRICK-AND-MORTAR STORE. PAGE 5 GAP’S INCOMING CEO XXXXXX Peck Picks His Team: Xxx Xxx Xxx Unveils Major Shake-Up Xxx Xxx Xxx Xxx By DAVID MOIN By OVIDIS A NATQUE NET ART PECK isn’t wasting any time at Gap Inc. Although he doesn’t offi cially take the reins of chief MENDA VOLUPTA turepudit, quias nestis accus as executive offi cer until February, succeeding Glenn resti beriasi doluptatem. Nem aut aperunto est ut Murphy, Peck is showing his impatience with the re- perrori taquidem aut qui blatem ad eium fugiantur tailer’s ongoing lackluster performance by shaking up modi cus vel iusam fugiamus, omnim volendus, sinus its management. On Thursday, he named new heads eaquas dolorep tatatent qui que sandelendis quis aut FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 21, 2014 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY for the Gap and Banana Republic divisions. voluptur? Jeff Kirwan, 48, for the past three years president Nam essint aut ea duntinv elendiciam num exp- WWD labo ribusae niam quidebi ssimet autat. of greater China for Gap Inc., will become global president for Gap brand in December. He succeeds Antiur, nobit faceptat. Stephen Sunnucks, who will leave the company on Idis molupti nonsequis doloren impelecae nusci Dec. -

Target's Challenge Lessons from Nasty

LESSONS FROM TARGET’S CHALLENGE The embattled retailer faces a tough task in fi nding NASTY GAL a replacement for Gregg Steinhafel, who stepped Sophia Amoruso talks down as chairman and chief executive offi cer. about her new book, PAGE 10 “#GirlBoss.” PAGE 7 WWDTUESDAY, MAY 6, 2014 ■ $3.00 ■ WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY WhiteThe dress code for men at The Costume Institute gala at TheHot Metropolitan Museum of Art Monday night stipulated “white tie and decorations,” but Rihanna upped the ante — and the sexiness — with some white of her own in the form of her Stella McCartney gown. For more on the event, which marked the opening of the “Charles James: Beyond Fashion” exhibition, see pages 4 and 5. PHOTO BY EVAN FALK 2 WWD TUESDAY, MAY 6, 2014 WWD.COM John Lewis Marks 150th Anniversary THE BRIEFING BOX To mark the anniversary, the store has IN TODAY’S WWD By LORELEI MARFIL launched a business incubator known as JLab, which aims to identify and develop LONDON — John Lewis is marking technology innovations that will shape 150 years in retail with a clutch of the shopping experience of the future. Joe Zee with Laura and Kate Mulleavy at a cocktail party on Sunday forward-looking projects — and a dash of The festivities officially began Saturday at Curve on Bond Street. For more, see page 11 and WWD.com. nostalgia. The British retailer, founded as with an interactive, 8,202-square-foot exhibi- a draper’s shop in 1864 by an orphan called tion at the Oxford Circus flagship that high- John Lewis, may not be nearly as glamorous lights the retailer’s history. -

Roger Ebert Hav Ing Once Made the Statement Abov E, I Hav E Declined All Opportunities to

In Memoriam 1942 – 2013 | ROGEREBERT..COM Choose a Section REVIEWS PITCH PERFECT 2 | Susan Wloszczyna May 15, 2015 | 9 As second rounds of comedies go, “Pitch Perfect 2” definitely is not perfect. Its script is more than a smidge pitchy. And there are at least two reasons to protest its Print Page treatment of Anna Kendrick’s Beca, the once outsider freshman who took the all-girl Barden Bellas to new competitive a capella heights in the sharp, sassy and Like sweetly humble original film that sprouted into an eminently re-watchable sleeper success mostly via DVD and cable in 2012. Like 12 First, not only is the diminutive dynamo subjected to bouts of abuse about her lack of height in the form of two towering Teutonic twits from a rival group known as 3 Das Sound Machine, now that the Bellas are competing on an international level. (Although her weird girl-crush on the intimidating Valkyrie-like female half of this bullying pair at least gives Kendrick something amusing to chew on). But on top of that, Beca’s very presence in the film has been shrunk. In fact, she spends much of her senior year guiltily sneaking off to an internship at a recording studio to pursue her dream of being a music producer instead of devoting herself to boosting her fellow Bellas. That also means less time cuddling with tenor Jesse (Skylar Astin), whose all-boy Treblemakers are now more cohorts than foes. The one upside: As her distracted boss, Keegan-Michael Key delivers a stellar slam against hipsterdom involving that mystifyingly popular sauce known as sriracha. -

Inside Forbes' Historic $10 Billion Richest Self-Made Women Cover - Forbes Page 1 of 5

Inside Forbes' Historic $10 Billion Richest Self-Made Women Cover - Forbes Page 1 of 5 Clare O'ConnorForbes Staff Women entrepreneurs and workplace equality. ENTREPRENEURS 6/01/2016 @ 7:58AM 172,373 views Inside Forbes' Historic $10 Billion Richest Self-Made Women Cover Photo: Jamal Toppin with Tim Pannell. We couldn’t decide on just one cover star for Forbes’ second annual Richest Self-Made Women issue, so we went with nine. For the first cover shoot of its kind, Forbes gathered nine of the most successful women entrepreneurs in the country, ranging in age from 32 to 69. They include a Silicon Valley CEO, a supermodel- turned-mogul, and a billionaire inventor. Between them, there are as many Harvard MBAs as there are community college dropouts. Combined, these nine women are worth $9.7 billion. On the front panel, the list’s richest member, 69- year-old roofing supply tycoon Diane Hendricks, flanks one of its youngest, 32-year-old Sophia Amoruso, founder of e-commerce fashion company Nasty Gal. To their left is Sara Blakely, founder of shapewear empire Spanx and the youngest self-made woman billionaire in the U.S. Meet all nine, from left to right: http://www.forbes.com/sites/clareoconnor/2016/06/01/inside-forbes-historic-10-billion-rich... 6/9/2016 Inside Forbes' Historic $10 Billion Richest Self-Made Women Cover - Forbes Page 2 of 5 Sara Blakely Net worth: $1 billion Sara Blakely is back running Spanx day-to-day following CEO Jan Singer’s exit. The former Nike exec helped expand the brand into athleisure wear but lasted less than two years in the job. -

Nomination Press Release

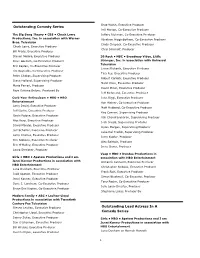

Brad Walsh, Executive Producer Outstanding Comedy Series Jeff Morton, Co-Executive Producer The Big Bang Theory • CBS • Chuck Lorre Jeffery Richman, Co-Executive Producer Productions, Inc. in association with Warner Abraham Higginbotham, Co-Executive Producer Bros. Television Cindy Chupack, Co-Executive Producer Chuck Lorre, Executive Producer Chris Smirnoff, Producer Bill Prady, Executive Producer Steven Molaro, Executive Producer 30 Rock • NBC • Broadway Video, Little Dave Goetsch, Co-Executive Producer Stranger, Inc. in association with Universal Television Eric Kaplan, Co-Executive Producer Lorne Michaels, Executive Producer Jim Reynolds, Co-Executive Producer Tina Fey, Executive Producer Peter Chakos, Supervising Producer Robert Carlock, Executive Producer Steve Holland, Supervising Producer Marci Klein, Executive Producer Maria Ferrari, Producer David Miner, Executive Producer Faye Oshima Belyeu, Produced By Jeff Richmond, Executive Producer Curb Your Enthusiasm • HBO • HBO John Riggi, Executive Producer Entertainment Ron Weiner, Co-Executive Producer Larry David, Executive Producer Matt Hubbard, Co-Executive Producer Jeff Garlin, Executive Producer Kay Cannon, Supervising Producer Gavin Polone, Executive Producer Vali Chandrasekaran, Supervising Producer Alec Berg, Executive Producer Josh Siegal, Supervising Producer David Mandel, Executive Producer Dylan Morgan, Supervising Producer Jeff Schaffer, Executive Producer Luke Del Tredici, Supervising Producer Larry Charles, Executive Producer Jerry Kupfer, Producer Tim Gibbons, Executive -

Coming to Campus: NEW DEGREE PROGRAMS and FACILITIES

THEUNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I –HOOT WEST O‘AHU — NOVEMBER 2017 Coming to Campus: NEW DEGREE PROGRAMS AND FACILITIES Page 7 PLUS: UHWO AMPHITHEATER • FREE YOGA • SPLASH BASH University of Hawaiʻi - West Oʻahu THE HOOT Student Newspaper 91-1001 Farrington Hwy · Kapolei, HI 96707 Editor’s Note awaii is the most fields of sugarcane were replaced by suburban Editor-in-Chief Austin Wandasan H expensive state to sprawl (the old timers will be sure to tell you). live in. Everyone in Hawaii Just a year later in 1960, Hawaii took the Layout Editor Analyn Delos Santos knows this, but few know number one spot in the nation for having the Staff Writers Giovanni Aczon the reason why. In the highest ACSFH, $100,000 when adjusted. We Daniel Coronado 1960s, with the fall of the beat New York and California, and we still do Tancy Chee sugar industry in Hawaii, today. Lauren Galiza AUSTIN WANDASAN the Big Five turned to new The Big Five knew tourism was a get-rich- Coral Garcia EDITOR-IN-CHIEF industries: tourism and quick scheme, they knew it was unsustainable Rosalie Hobbs land development. and temporary. The real money would come Kurtis Macadamia The average cost of a single-family home from land development, i.e. real estate. Kinji Martin (ACSFH) is probably one of the most influential Tourism isn’t about filling the hotel rooms with Leo Ramirez Jr. factors in calculating the cost of living. In the tourists, it’s about getting them to stay. Ariana Savea free market, supply and demand dictate the By inflating demand and limiting supply, George F.