Special Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

Understanding the Origin of the Terms 'WUNG', 'HAO' and 'TANGKHUL'

International Research Journal of Social Sciences_____________________________________ ISSN 2319–3565 Vol. 3(5), 36-40, May (2014) Int. Res. J. Social Sci. Understanding the Origin of the terms ‘WUNG’, ‘HAO’ and ‘TANGKHUL’ Mawon Somingam Department of Cultural and Creative Studies, North-Eastern Hill University (NEHU) Shillong, Meghalaya, 793022, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 7th March 2014, revised 10 th April 2014, accepted 12 th May 2014 Abstract Understanding the origin and meaning of nomenclature of the ‘people’ or term referring to the ‘people’ is as important as identity of the people itself. At times, terms and nomenclatures of the ‘people’ are given by non locals. In the Naga context, the term ‘Naga’ itself is non-local, nomenclature of its federating tribes like Tangkhul is non-local, and names of many Tangkhul villages like Ukhrul, Tushen, Lambui, and Hundung etc. are given by non local administrators, missionaries, anthropologists and neighbouring communities among others. The core focus of the paper is to understand the origin of the terms WUNG, HAO and TANGKHUL. It also brings in the hypothesis of ‘Tangkhul-Meitei Origin’ while attempting to understand the people in brief. One of the main arguments of the paper is that the term HAO is the original or traditional nomenclature of the Tangkhul Nagas. Keywords : Wung, Hao, Tangkhul, Meitei, Christian and People. Introduction “Wung is no longer use today, neither by the people themselves, nor in official transaction” 5. However, it would be wrong to say Though there is no consensus among the local writers and that the term wung is no longer in use today. -

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Mollen Kamsei Primary School Mull

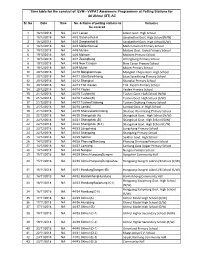

Time table for the conduct of EVM - VVPAT Awareness Programmes at Polling Stations for 44 Ukhrul (ST) AC Sl. No Date Time No. & Name of polling stations to Venue(s) be covered 1 18/12/2018 NA 44/1 Leisan Leisan Govt. High School 2 18/12/2018 NA 44/2 Sanakeithel-A Sanakeithel Govt. High School(N/W) 3 18/12/2018 NA 44/3 Sanakeithel-B Sanakeithel Govt. High School(S/W) 4 18/12/2018 NA 44/4 MollenKamsei Mollen Kamsei Primary School 5 19/12/2018 NA 44/5 Mullam Mullam Govt. Aided Primary School 6 19/12/2018 NA 44/6 Molnom Molnom Primary School 7 19/12/2018 NA 44/7 Zelengbung Zelengbung Primary School 8 19/12/2018 NA 44/8 New Canaan New Canan Primary School 9 19/12/2018 NA 44/9 Muirei Muirei Primary School 10 20/12/2018 NA 44/10 MongkotChepu Mongkot Chepu Govt. High School 11 20/12/2018 NA 44/11 LitanSareikhong Litan Sareikhong Primary School 12 20/12/2018 NA 44/12 Shangkai Shangkai Primary School 13 20/12/2018 NA 44/13 T.M. Kasom T.M. Kasom Primary School 14 20/12/2018 NA 44/14 Yaolen Yaolen Primary School 15 21/12/2018 NA 44/15 Tushen(A) Tushen Govt. High School (N/W) 16 21/12/2018 NA 44/16 Tushen(B) Tushen Govt. High School (S/W) 17 21/12/2018 NA 44/17 TushenChahong Tushen Chahong Primary School 18 21/12/2018 NA 44/18 Lambui Lambui Govt. Jr. -

Role of Traditional Homegardens in Biodiversity Conservation and Socioecological Significance in Tangkhul Community in Northeast India

Tropical Ecology 59(3): 533–539, 2018 ISSN 0564-3295 © International Society for Tropical Ecology www.tropecol.com Role of traditional homegardens in biodiversity conservation and socioecological significance in Tangkhul community in Northeast India TUISEM SHIMRAH1*, PEIMI LUNGLENG1, CHONSING SHIMRAH2, Y. S. C. KHUMAN3 & 4 FRANKY VARAH 1University School of Environment Management, GGSIP University, New Delhi 2Department of Anthropology, Delhi University, Delhi 3School of Inter-Disciplinary and Trans-Disciplinary Studies, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi. 4Department of Environmental Studies, Bhaskaracharya College of Applied Science, Delhi University, New Delhi Abstract: Traditional communities in various parts of the world are facing various challenges owing to shrinking per capita land availability and growing market economy. This has led to shift in land use in which polyculture of variety of traditional crops are being slowly replaced by market driven monoculture system of cultivation to meet the demands to market on one side and maximization of production on the other side. As a result, the traditional crops in homegarden are being threatened in many areas. A study on conservation of tradition crops in homegarden in Tangkhul community in Ukhrul District of Manipur, India was carried out to assess the impact of such change in terms of crop species and their socioecological significance. A total of 73 plant species of economic, social and cultural values belonging to 27 families were recorded in homegardens. Result of this study shows that Tangkhul traditional community has vast indigenous knowledge on conservation of biodiversity in limited homegarden sites. Understanding traditional knowledge concerning HGs and how this form the knowledge for choice of species across the local community could help developing better strategies for sustainable management of traditional homegarden. -

3 August Page 1

The only English Eveningdaily in Imphal daily IND No. Plate broken Due to technical problem I, the undersigned, do hereby declare that My IND No. Plate of my vehicle (Fortuner 3.02.2wd Imphal Times have only 2 bearing registration number MN02B 8963 issued by the Transport department government of page publication for some Manipur has been broken in a minor accident on July 10,2018. days. We will continue 4 Sd/- page edition after we Puyam Bobi Singh solve our problem. Imphal Times Uchekon TakhokMapal, Imphal East Irilbung, Manipur Editor Regd.No. MANENG /2013/51092 Volume 6, Issue 186, Friday, Aug 3, 2018 www.imphaltimes.com Maliyapham Palcha Kumshing 3416 2/- Protest against FA gaining DC denies permission to all political parties momentum Women bodies storms at MP Bhavananda residence; students rally in support of MU community IT News Gheroa BJP office; Muslim’s body IT News precede the rally despite the Imphal, Aug.3, Imphal, Aug 3, objection saying that the rally stage sit-in-protest is not going to give any Protest against Frame Work Solidarity rally by disturbance to either the traffic Agreement between the representatives of various movement as well as NCSN IM and the government political parties of the state and tranquility of the area saying of India which hinted veteran politicians organized that the rally is a peace rally to administrative division in the by locals from the surrounding show solidarity to the agitation state of Manipur is gaining of the Manipur University was by the Manipur University momentum with various civil denied permission by the community which demand society bodies as well as District Magistrate of Imphal removal of the MU Vice student’s body stage protest West today. -

Medicinal Plants Research

V O L U M E -III Glimpses of CCRAS Contributions (50 Glorious Years) MEDICINAL PLANTS RESEARCH CENTRAL COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH IN AYURVEDIC SCIENCES Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India New Delhi Illllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Glimpses of CCRAS contributions (50 Glorious years) VOLUME-III MEDICINAL PLANTS RESEARCH CENTRAL COUNCIL FOR RESEARCH IN AYURVEDIC SCIENCES Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India New Delhi MiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiM Illllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll © Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India, New Delhi - 110058 First Edition - 2018 Publisher: Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences, Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India, New Delhi, J. L. N. B. C. A. H. Anusandhan Bhavan, 61-65, Institutional Area, Opp. D-Block, Janakpuri, New Delhi - 110 058, E-mail: [email protected], Website : www.ccras.nic.in ISBN : 978-93-83864-27-0 Disclaimer: All possible efforts have been made to ensure the correctness of the contents. However Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences, Ministry of AYUSH, shall not be accountable for any inadvertent error in the content. Corrective measures shall be taken up once such errors are brought -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of India Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues REPUBLIC OF INDIA Submitted by: C.R Bijoy and Tiplut Nongbri Last updated: January 2013 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues – Republic of India ......................... 1 1.1 Definition .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Scheduled Tribes ......................................................................................... 4 2. Status of scheduled tribes ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 Occupation ........................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Sl. No. Form No. Name Address District Catego Ry Status Recommendation of the Screening Commit

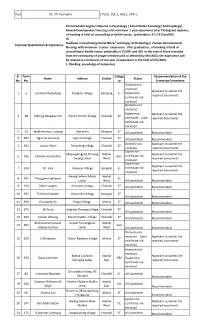

Post A1: STI Counselor 3 Posts: CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Post Graduate degree I diploma in Psychology / Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Nursing; with minimum 1 year experience after PG degree/ diploma, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI / RTI and HIV. Or Graduate in Psychology/Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Essential Qualification & Experience: Nursing; with minimum 3 years .experience after graduation, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI/RTI and HIV. In the case of those recruited from the community of people infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, the experience will be relaxed to a minimum of one year of experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. 1. Working knowledge of computers Sl. Form Catego Recommendation of the Name Address District Status No. No. ry Screening Committee Domicile not enclosed, Applicant to submit the 1 2 Lanmila Khapudang Kongkan Village Kamjong ST Experience required documents certificate not enclosed Domicile not enclosed, Experience Applicant to submit the 2 38 Dilbung Rengwar Eric Purum Pantha Village Chandel ST certificate , Caste required documents certificate not enclosed 3 54 Makhreluibou Luikang Makhrelu Senapati ST All submitted Recommended 4 483 Ngorum Kennedy Japhou Village Chandel ST All submitted Recommended Domicile not Applicant to submit the 5 564 Jacinta Telen Penaching Village Chandel ST enclosed required documents Experience Mayanglangjing Tamang Imphal Applicant to submit the 6 756 -

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Consultancy Services for Preparation of Detailed Project Report DETAILED PROJECT REPORT for 2 Laning of Longpi Kajui-Razai/ Chingjaroi Khullen Road on NH 202 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 0.1 GENERAL National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has decided to take up the development of various National Highways Corridors in the North-eastern state where the intensity of traffic has increased significantly in plain areas and where there is requirement of safe and efficient movement of traffic mainly in hilly terrains. This project is a part of the above mentioned programme and the project awarded to Consultant is Consultancy Services for carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning of Yaingangpokpi-Nagaland Border in the state of Manipur. Project Stretch: Longpi Kajui-Razai/ Chingjaroi Khullen (25.448Km). The NHIDCL has been entrusted with implementation of the development of this corridor from Ministry’s Plan Funds. In order to fulfil the above task, NHIDCL has entrusted the work of preparation of the feasibility study and Detailed Project Report for the above project to M/s S. M. Consultants., vide contract agreement dated 19th January 2017. The Letter of Acceptance was communicated vide letter No NHIDCL/DPR/IM&UJ/Manipur/2016/293. 0.2 OBJECTIVE The main objectives of the consultancy service will focus on establishing technical, financial viability of the project and prepare detailed project reports for rehabilitation/ upgradation/ construction of the existing road to two lane NH with paved shoulder configuration with the following points to be ensured. -

COVID-19 Pandemic a Warning to Mankind : Experts and Openly Declaring Sup- Held Earlier

JNIMS clarifies Fear, anxiety, apprehension grip Ukhrul as... IMPHAL, Jun 28: The Lockdown to be Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Medical Sciences (JNIMS) has clarified to the query extended till Jul 15 First report of 25 says negative, second says positive raised by Democratic Stu- Mungchan Zimik lage of Ukhrul. dents Alliance of Manipur Meanwhile the convener (DESAM) that there are 150 UKHRUL, Jun 28 : Fear, of Tangkhul Co-ordination dedicated COVID beds with anxiety and apprehension Forum on COVID-19 bed occupancy of 140 to 150 have gripped Ukhrul district (TCFC -19) K Tuisem tak- per day. after 25 persons who were ing the development "All the daily wastes gen- declared negative after their seriously questioned the per- erated from COVID wards samples were tested were sons (microbiologists) like PPE, caps, face cover, again declared to be positive handling the test lab at shoe cover, gloves, face within a span of 24 hours. RIMS and asserted that they masks, etc are treated with Twenty five persons who should be held accountable sodium hypochlorite solu- were declared negative of for the faulty test result. tion and then collected in the dreaded virus on June 26 In case there is commu- double layered polythene however found that they had nity spread, the persons bags and then burnt in the tested positive on June 27. concerned including the Incinerator Plant," said Dr The samples of the 25 Health Department should Rajen Singh in a statement IMPHAL, Jun 28 (DIPR) persons were collected on be held responsible, he as- on plain paper. June 22 and June 23 and the serted.