CREATION in the PERFUME WORLD Jean-Claude Ellena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2011 Contents

Annual Report 2011 Contents Overview Sustainable business model 2 Financial highlights 46 Sustainable business model 3 Distinct capabilities 46 – Compliance 4 Our business 47 – Shareholders (2011) 6 Key events of the year 48 – Customers 8 Chairman’s letter 49 – Our people 10 Chief Executive’s review 52 – Suppliers Strategy 52 – Supply chain 53 – Information technology 16 Developing markets 53 – Environment, Health and Safety (EHS) 18 Research and Development 55 – Risk management 26 Health and Wellness 57 – Regulatory 28 Sustainable sourcing of raw materials 30 Targeted customers and segments Corporate governance Performance 60 Corporate governance 60 – Group structure and shareholders 34 Business performance 61 – Capital structure 36 Fragrance Division 62 – Board of Directors 37 – Fine Fragrances 72 – Executive Committee 38 – Consumer Products 75 – Compensation, shareholdings and loans 39 – Fragrance Ingredients 75 – Shareholders’ participation 39 – Research and Development 76 – Change of control and defence measures 40 Flavour Division 77 – Auditors 41 – Asia Pacific 77 – Information policy 42 – Europe, Africa, Middle East (EAME) 78 Compensation report 43 – North America 43 – Latin America Financial report 43 – Research and Development 87 Financial review 90 Consolidated financial statements 95 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 145 Report of the statutory auditors on the consolidated financial statements 146 Statutory financial statements of Givaudan SA 148 Notes to the statutory financial statements 152 Appropriation of available earnings of Givaudan SA 153 Report of the statutory auditors on the financial statements Our Brand: Engaging the Senses Introduction As the leading company in the fragrance and flavour industry, Givaudan develops unique and innovative fragrance and flavour creations for its customers around the world. -

2020 Governance, Compensation and Financial Report Ements

Governance, Compensation and Financial Report 2020 Governance, Compensation Governance report and Financial Report As part of our reporting suite, this stand-alone document contains the full details of our governance and compensation policies as well as the details of our financial performance. Compensation Compensation report An overview can be found in the Integrated Annual Report. Consolidated Consolidated report financial Statutory report financial Table of contents 3 Governance report 22 Compensation report 38 Consolidated financial report 102 Statutory financial report Appendix 114 Appendix Governance Report In this section 4 Group structure and shareholders 5 Capital structure 7 Board of Directors 16 Executive Committee 19 Compensation, shareholdings and loans 19 Shareholders’ participation 20 Change of control and defence measures 20 Auditors 21 Information policy Givaudan – 2020 Governance, Compensation and Financial Report 4 Corporate governance Governance report Ensuring proper checks and balances 1. Group structure and shareholders The Governance report is aligned with 1.1 Group structure 1.1.1 Description of the issuer’s operational Group structure international standards and has been prepared Givaudan SA, the parent company of the Givaudan Group, with its registered corporate headquarters at 5 Chemin de la Parfumerie, 1214 Vernier, Switzerland (‘the Company’), is a in accordance with the ‘Swiss Code of Obligations’, ‘société anonyme’, pursuant to art. 620 et seq. of the Swiss Code of Obligations. It is listed on Compensation Compensation report the ‘Directive on Information Relating to the SIX Swiss Exchange under security number 1064593, ISIN CH0010645932. Corporate Governance’ issued by the SIX Swiss The Company is a global leader in its industry. Givaudan operates around the world and has two principal businesses: Taste & Wellbeing and Fragrance & Beauty, providing customers Exchange and the ‘Swiss Code of Best Practice for with compounds, ingredients and integrated solutions. -

New Launches News

the scent post A MONTHLY UPDATE ON THE LATEST FRAGRANCE NEWS new launches top new videos poison girl roller pearl | DIOR les merveilleuses ladurée arizona coco mademoiselle intense english fields LADURÉE PROENZA SCHOULER CHANEL JO MALONE NEW FRAGRANCE NEW FRAGRANCE RANGE EXTENSION LIMITED EDITION news arizona | PROENZA SCHOULER elevator music hermè s creates a sense of miller harris’ concept meta cacti the fragrance created by ritual around its scents store heightens the by chiaozza byredo and off-white senses in canary wharf x régime des fleurs x | brrch floral coco mademoiselle edp intense CHANEL FRAGRANCE NEWS hermessence Hermès creates a sense of ritual around its scents Fashion house Hermès is expanding its perfume offering with a new range consisting of eaux de toilette and essences de parfum scents. Part of its Hermessence collection, the oil-based essences de parfum mark a departure for the brand, which has until now only created the lighter eaux de toilette. Intended to be worn either as a base for other fragrances or on their own, the fragrances add an additional layer to the ritual of putting on perfume, an idea explored in the Multisensory Beauty microtrend. The musk-based scent profiles, Cardamusc and Musc Pallida, draw on cardamom and iris oils, both of which are known for their wellness properties, including use as a decongestant. In line with Psychoactive Scents, as the wellness and beauty sectors become increasingly entwined, brands are exploring new ways to combine the properties of essential oils with high-end scents. FRAGRANCE NEWS miller harris’ concept store heightens the senses A very vibrant force has landed in Cabot Place, Canary Wharf. -

Male Fragrances That Evoke a Feral Growl, Full-Blown Tempests Or The

A WHIFF OF DANGER Male fragrances that evoke a feral growl, full-blown tempests or the swaggering brio of ancient Rome are a bullseye for those who embrace their masculinity, says Lucia van der Post. Photograph by Omer Knaz he first scent I ever truly fell in love with was Schiaparelli’s Shocking, made by the great Jean Carles, and I came across it because my father wore it. I still remember the shock of pleasure when that first light floral note hit me, then the sense of surprise as the herbs, sandalwood and honey began to emerge, and finally it became sexier and more earthy as the oakmoss and what I now know Tto be civet took over. I remember, too, old-fashioned child that I was, that I thought it strange that my markedly heterosexual father wore a scent that seemed so voluptuous and so clearly aimed at women. Today, nobody would think anything of it. Speak to connoisseurs of perfume and as one they reject the notion of male and female scents. As Roja Dove, éminence grise of the perfume world, puts it: “For years floral notes were associated with feminine perfumes and – since men were considered strutting, predatory things – woody, mossy, earthy materials were linked with masculine ones, but the boundaries nowadays have become much more blurred. A rose, after all, has neither a penis nor a vagina – a rose on a man is a masculine rose, a rose on a woman is a feminine rose.” Violet, a note that one would have thought was largely feminine, was much beloved by Italian dandies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and it was an overdose of violet that made Geoffrey Beene’s Grey Flannel (£45 for 60ml EDT, to which much-respected perfume scholar Luca Turin awards five stars, calling it “a masterpiece”) such a success when it was launched in Clockwise from far left: 1975. -

Basic Perfume Primer

THE INSTITUTE FOR ART AND OLFACTION BASIC PERFUME PRIMER TABLE OF CONTENTS • About the IAO o Mission statement o Philosophy o This primer • Taxonomies: o Top, middle, base o Fragrance families • Materials: o Aromatic chemicals o Naturals, synthetics, accords o Essential oil vs. absolute vs. etc. • Working with Scent: o Working with the materials o Lab safety basics o Pipettes, scent strips, beakers o Techniques for Smelling o IAO best practices ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT This document was prepared by staff and instructors at the Institute for Art and Olfaction, with a view of providing some foundational knowledge for IAO students and curious minds just coming to perfumery. Contributors include Ashley Eden Kessler, Minetta Rogers, Saskia Wilson-Brown and Timothy Van Ausdal, as well as online sources such as The Fragrance Society, The Perfume Expert, Mandy Aftel, Michael Edwards, Wikipedia and Science for New Students. We invite you to share this information under the guides of the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this work - even for commercial purposes - as long as they credit the IAO and other contributors, and license their new creations under the identical terms. With this license, you are free to share (copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format) and adapt (remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially) this work. The IAO cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. ABOUT THE IAO MISSION STATEMENT Founded in September 2012 in Los Angeles, The Institute for Art and Olfaction is a 501(c)3 non- profit devoted to advancing public, artistic and experimental engagement with scent. -

Perfume Engineering Perfume Engineering Design, Performance & Classification

Perfume Engineering Perfume Engineering Design, Performance & Classification Miguel A. Teixeira, Oscar Rodríguez, Paula Gomes, Vera Mata, Alírio E. Rodrigues Laboratory of Separation and Reaction Engineering (LSRE) Associate Laboratory Department of Chemical Engineering Faculty of Engineering of University of Porto Porto, Portugal P. Gomes and V. Mata are currently at i-sensis company S. João da Madeira, Portugal AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Butterworth-Heinemann is an imprint of Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann is an imprint of Elsevier The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford, OX5 1GB, UK 225 Wyman Street, Waltham, MA 02451, USA First published 2013 Copyright r 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangement with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. -

Fragonard Magazine N°9 - 2021 a Year of PUBLICATION DIRECTOR and CHIEF EDITOR New Charlotte Urbain Assisted By, Beginnings Joséphine Pichard Et Ilona Dubois !

MAGAZINE 2021 9 ENGLISH EDITORIAL STAFF directed by, 2021, Table of Contents Agnès Costa Fragonard magazine n°9 - 2021 a year of PUBLICATION DIRECTOR AND CHIEF EDITOR new Charlotte Urbain assisted by, beginnings Joséphine Pichard et Ilona Dubois ! ART DIRECTOR Claudie Dubost assisted by, Maria Zak BREATHE SHARE P04 Passion flower P82 Audrey’s little house in Picardy AUTHORS Louise Andrier P10 News P92 Passion on the plate recipes Jean Huèges P14 Laura Daniel, a 100%-connected by Jacques Chibois Joséphine Pichard new talent! P96 Jean Flores & Théâtre de Grasse P16 Les Fleurs du Parfumeur Charlotte Urbain 2020 will remain etched in our minds as the in which we all take more care of our planet, CELEBRATE CONTRIBUTORS year that upturned our lives. Yet, even though our behavior and our fellow men and women. MEET P98 Ten years of acquisitions at the Céline Principiano, Carole Blumenfeld we’ve all suffered from the pandemic, it has And especially, let’s pledge to turn those words P22 Musée Jean-Honoré Fragonard leading the way Eva Lorenzini taught us how to adapt and behave differently. into actions! P106 A-Z of a Centenary P24 Gérard-Noel Delansay, Clément Trouche As many of you know, Maison Fragonard is a Although uncertainty remains as to the Homage to Jean-François Costa a familly affair small, 100% family-owned French house. We reopening of social venues, and we continue P114 Provence lifestyle PHOTOGRAPHERS enjoy a very close relationship with our teams to feel the way in terms of what tomorrow will in the age of Fragonard ESCAPE Olivier Capp and customers alike, so we deeply appreciate bring, we are over the moon to bring you these P118 The art of wearing perfume P26 Viva România! Eva Lorenzini your loyalty. -

Analysis of Impression Evaluation of Fragrances Associated with ‘Omotenashi’ in Elderly People Using Perfumes – Including Comparative with Young People –

TInrtaenrsnaactitoionnasl Joof uJranpaal no fS Aofcfeiecttyiv oef EKnagnisneie Eringineering J-STAGE Advance Published Date: 2020.09.16 doi: 10.5057/ijae.IJAE-D-20-00016 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Analysis of Impression Evaluation of Fragrances Associated with ‘Omotenashi’ in Elderly People using Perfumes – Including Comparative with Young People – Harumi NAKAGAWA and Noriaki KUWAHARA Kyoto Institute of Technology, Matsugasaki, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8585, Japan Abstract: In this study, we used 6 different fragrances to better understand the tendency of scents to elicit a sense of omotenashi (hospitality) in elderly people. To first understand how elderly people perceive scents associated with feelings of omotenashi we performed an impression evaluation using SD method of 22 adjective pairs. We then analyzed the results taken from a questionnaire survey we conducted on 51 elderly Japanese men and women using a factor analysis, and extracted the factors that represent sensations of scents which produced a sense of omotenashi. Our subsequent examination of the main underlying factors indicated that scents with sensations of freshness, adulthood and pleasure hinted a sense of omotenashi in scents for elderly people. We also noted differences in the way the scent was perceived compared to young people. Keywords: Elderly, SD method, Fragrances Japan’s super-aged society, Shiizuka proposes a frame- 1. INTRODUCTION work for leveraging the ‘meta-kansei engineering’ method. The proposal, based on data from the White Paper on How much information do we receive and perceive Ageing Society published by the Cabinet Office, provides from scents in 24 hours of our daily lives? The informa- examples of training the five senses, including the sense tion on these scents is will differ depending on the kansei of smell and “expressing different fragrances” [4]. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: August 13, 2006. I, Grettel Zamora-Estrada , hereby submit this work as a part of the requirements of the degree of: Master of Science (M.S.) . in: Pharmaceutical Sciences . It is entitled: Partitioning of Perfume Raw Materials in Conditioning Shampoos using Gel Network Technology________________________________________ ty . This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Gerald B. Kasting, Ph. D. _____________ R. Randall Wickett, Ph.D. Eric S. Johnson, Ph.D. Kevin M. Labitzke, A.S. _ . Partitioning of Perfume Raw Materials in Conditioning Shampoos using Gel Network Technology by Grettel Zamora-Estrada A dissertation proposal synopsis Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of M.S. Pharmaceutical Sciences University of Cincinnati College of Pharmacy Cincinnati, Ohio July 23, 2006 ii ABSTRACT Gel network technology in conditioning shampoo represents an advantage over traditional silicone 2-in-1 technology due to its main benefits: dry conditioning, wet feel and lower cost. The purpose of this study was to do a proof of principle investigation and to study the main factors that affected partitioning of PRMs into the gel network system shampoos and determine the effect that perfume incorporation had on the shampoo stability of the different formulations . Gel network premixes (literally a conditioner) were formulated then incorporated into a standard shampoo base. Changes in formulation of the gel network such as chain length of fatty alcohols and fatty alcohol ratios were done and its effect on stability and perfume migration studied. A technical accord with 25 PRMs with a very wide range of physical properties was used as a marker. -

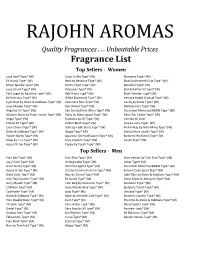

Fragrance List Print

Quality Fragrances . Unbeatable Prices Fragrance List Top Sellers - Women Love Spell Type* (W) Gucci Guilty Type* (W) Romance Type* (W) Ed Hardy Type*RAJOHN (W) Heat by Beyonce Type* (W)AROMASBlack by Kenneth Cole Type* (W) Moon Sparkle Type* (W) Jimmy Choo Type* (W) Beautiful Type* (W) Love Struck Type* (W) Pleasures Type* (W) Bombshell by VS Type* (W) Pink Sugar by Aquolina Type* (W) Reb'l Fleur Type* (W) Black Woman Type* (W) Be Delicious Type* (W) White Diamonds Type* (W) Versace Bright Crystsal Type* (W) Light Blue by Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Cashmere Mist Type* (W) Candy by Prada Type* (W) Issey Miyake Type* (W) Butt Naked Type* (W) Michael Kors Type* (W) Angel by VS Type* (W) Can Can by Paris Hilton Type* (W) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* (W) Modern Muse by Estee Lauder Type* (W) Daisy by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Miss Dior Cherie Type* (W) Angel Type* (W) Euphoria by CK Type* (W) Lick Me All Over Chanel #5 Type* (W) Amber Blush Type* (W) Viva La Juicy Type* (W) Coco Chanel Type* (W) Halle by Halle Berry Type* (W) Pink Friday by Nicki Minaj Type* (W) Dolce & Gabbana Type* (W) Happy Type* (W) Dot by Marc Jacobs Type* (W) Flower Bomb Type* (W) Japanese Cherry Blossom Type* (W) Burberry Weekend Type* (W) Glow by J. Lo Type* (W) Juicy Couture Type* (W) Coach Type* (W) Acqua Di Gio Type* (W) Poppy by Coach Type* (W) Top Sellers - Men Polo Red Type* (M) Polo Blue Type* (M) Grey Vetiver by Tom Ford Type* (M) Jay-Z Gold Type* (M) Unforgivable Type* (M) Usher Type* (M) Gucci Guilty Type* (M) Chrome Legend Type* (M) Cucumber Melon by B&BW Type* -

Perfumes and Their Preparation, by George William Askinson

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Perfumes and their Preparation, by George William Askinson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Perfumes and their Preparation Containing complete directions for making handkerchief perfumes, smelling-salts, sachets, fumigating pastils;... Author: George William Askinson Translator: Isidor Furst Release Date: October 12, 2017 [EBook #55735] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PERFUMES AND THEIR PREPARATION *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive) PERFUMES AND THEIR PREPARATION. CONTAINING COMPLETE DIRECTIONS FOR MAKING HANDKERCHIEF PERFUMES, SMELLING-SALTS, SACHETS, FUMIGATING PASTILS; PREPARATIONS FOR THE CARE OF THE SKIN, THE MOUTH, THE HAIR; COSMETICS, HAIR DYES, AND OTHER TOILET ARTICLES. WITH A DETAILED DESCRIPTION OF AROMATIC SUBSTANCES; THEIR NATURE, TESTS OF PURITY, AND WHOLESALE MANUFACTURE. BY GEORGE WILLIAM ASKINSON, DR. CHEM., MANUFACTURER OF PERFUMERY. TRANSLATED FROM THE THIRD GERMAN EDITION BY ISIDOR FURST. (WITH CORRECTIONS AND ADDITIONS BY SEVERAL EXPERTS.) Illustrated with 32 Engravings. NEW YORK: LONDON: N. W. HENLEY & CO., E. -

ESQ Junjul20

Portfolio Portfolio Feature Feature NOTES FROM THE PERFUME INDUSTRY Olivier Pescheux Givaudan perfumer A Creations: 34 boulevard Saint Germain Diptyque, Amber Sky Ex Nihilo, Arpege Pour Homme Lanvin, 1 Million Paco Rabanne, Balmain Homme Pierre Balmain, Higher Christan Dior ESQ: In hindsight, do you find that trends, current events or cultural movements have an impact on your creations? OLIVIER PESCHEUX: It’s hard to answer with certainty. Nevertheless, perfumers are like sponges absorbing the air of time (Nina Ricci’s L’Air du Temps is one of the most accurate names you can find). Hence every societal movement leaves its mark on creations, in a more or less obvious way. It’s still too early to know in IN what ways the current health crisis will leave its mark in perfume, but it will leave its mark, that’s for sure. ESQ: Do you attribute gender to certain notes and raw materials? OLIVIER PESCHEUX : Not really, but it’s true that I perceive rose as rather feminine simply because it has been used a lot THE and in significant quantities in women’s fragrances in the West. That’s less true in the Middle East, where the rose also perfumes men. Lavender is rather masculine as it’s used a lot in fougère, the favourite family of men’s fragrances. It’s interesting to note that in Brazil, lavender is also feminine. So it’s more of a cultural affair. Yann Vasnier I’m trying to fight against this natural and cultural leaning, and on Givaudan perfumer the contrary, I use this challenge to fuel my creativity.