Roman Bridges (Edited from Wikipedia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By the Persian Mathematician and Engineer Abubakr

1 2 The millennium old hydrogeology textbook “The Extraction of Hidden Waters” by the Persian 3 mathematician and engineer Abubakr Mohammad Karaji (c. 953 – c. 1029) 4 5 Behzad Ataie-Ashtiania,b, Craig T. Simmonsa 6 7 a National Centre for Groundwater Research and Training and College of Science & Engineering, 8 Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia 9 b Department of Civil Engineering, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran, 10 [email protected] (B. Ataie-Ashtiani) 11 [email protected] (C. T. Simmons) 12 13 14 15 Hydrology and Earth System Sciences (HESS) 16 Special issue ‘History of Hydrology’ 17 18 Guest Editors: Okke Batelaan, Keith Beven, Chantal Gascuel-Odoux, Laurent Pfister, and Roberto Ranzi 19 20 1 21 22 Abstract 23 We revisit and shed light on the millennium old hydrogeology textbook “The Extraction of Hidden Waters” by the 24 Persian mathematician and engineer Karaji. Despite the nature of the understanding and conceptualization of the 25 world by the people of that time, ground-breaking ideas and descriptions of hydrological and hydrogeological 26 perceptions such as components of hydrological cycle, groundwater quality and even driving factors for 27 groundwater flow were presented in the book. Although some of these ideas may have been presented elsewhere, 28 to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a whole book was focused on different aspects of hydrology 29 and hydrogeology. More importantly, we are impressed that the book is composed in a way that covered all aspects 30 that are related to an engineering project including technical and construction issues, guidelines for maintenance, 31 and final delivery of the project when the development and construction was over. -

Waters of Rome Journal

TIBER RIVER BRIDGES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANCIENT CITY OF ROME Rabun Taylor [email protected] Introduction arly Rome is usually interpreted as a little ring of hilltop urban area, but also the everyday and long-term movements of E strongholds surrounding the valley that is today the Forum. populations. Much of the subsequent commentary is founded But Rome has also been, from the very beginnings, a riverside upon published research, both by myself and by others.2 community. No one doubts that the Tiber River introduced a Functionally, the bridges in Rome over the Tiber were commercial and strategic dimension to life in Rome: towns on of four types. A very few — perhaps only one permanent bridge navigable rivers, especially if they are near the river’s mouth, — were private or quasi-private, and served the purposes of enjoy obvious advantages. But access to and control of river their owners as well as the public. ThePons Agrippae, discussed traffic is only one aspect of riparian power and responsibility. below, may fall into this category; we are even told of a case in This was not just a river town; it presided over the junction of the late Republic in which a special bridge was built across the a river and a highway. Adding to its importance is the fact that Tiber in order to provide access to the Transtiberine tomb of the river was a political and military boundary between Etruria the deceased during the funeral.3 The second type (Pons Fabri- and Latium, two cultural domains, which in early times were cius, Pons Cestius, Pons Neronianus, Pons Aelius, Pons Aure- often at war. -

Roman Mortars Used in the Archaeological Sites In

UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA DE MADRID ESCUELA TÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE ARQUITECTURA ROMAN MORTARS USED IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES IN SPAIN AND TURKEY A COMPARATIVE STUDY AND THE DESIGN OF REPAIR MORTARS TESIS DOCTORAL DUYGU ERGENÇ Ingeniera Geológica y Máster en Restauración Junio 2017 CONSERVACIÓN Y RESTAURACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO ARQUITECTÓNICO ESCUELA T ÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE ARQUITECTURA DE MADRID ROMAN MORTARS USED IN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES IN SPAIN AND TURKEY A COMPARATIVE STUDY AND THE DESIGN OF REPAIR MORTARS Autor: DUYGU ERGENÇ Ingeniera Geológica y Máster en Restauración Directores: Dr. Fco. David Sanz Arauz Doctor en Arquitectura por ETSAM, UPM Dr. Rafael Fort González Doctor en Geología Económica por UCM, Senior científico en Instituto de Geociencias (CSIC-UCM) 2017 TRIBUNAL Tribunal nombrado por el Mgfco. Y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 2017 Presidente: Vocales: Secretario: Suplentes: Realizado el acto de lectura y defensa de la Tesis Doctoral el día de de 2017 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid EL PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. To my family Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support and expertise of many people. First of all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisors, Dr. Fco. -

Summer in the Romantic Cities

PRESS RELEASE SUMMER IN THE ROMANTIC CITIES KOBLENZ, JUNE 2019 Enjoy outdoor activities, dancing and laughing! Summer in the Romantic Cities is all this and much more. Located in the southwest of Germany and blessed with a pleasant, Mediterranean climate, the cities of Rhineland‑ Palatinate are ideal for enjoying summer to the full, be it by attending the countless events or enjoying regional delicacies or the various outdoor activities. You will most definitely fall in love with the Romantic Cities straddling the Rhine and Moselle! EVENTS The season kicks off on the next-to-last weekend in June (19–23 June 2019) with the open- air Porta³ in front of the Porta Nigra in Trier, a grand celebration with big names in attendance, good music and a vibrant atmosphere. The Nibelungen Festival in Worms (12–28 July 2019) is more restrained but no less entertaining. This year, the open-air theatrical event just outside the cathedral will feature ‘ÜBERWÄLTIGUNG’. But it is not only the performance against a backdrop of the cathedral that makes the festival a unique cultural event, it is also the excellent supporting programme and Heylshof Garden, one of Germany’s most beautiful theatre foyers, that attract numerous visitors. The night sky is fantastically illuminated during the Mainz Summer Lights (26–28 July 2019), which includes a varied music programme, a welcoming wine village, countless food stalls, other activities and, the pièce de résistance on Saturday, a stunning fireworks display set to music. The breathtaking show can be enjoyed from the riverbanks or aboard an exclusive ship on the Rhine. -

Postclassicalarchaeologies

pceuropeana journal of postclassicalarchaeologies volume 8/2018 SAP Società Archeologica s.r.l. Mantova 2018 pca EDITORS EDITORIAL BOARD Gian Pietro Brogiolo (chief editor) Gilberto Artioli (Università degli Studi di Padova) Alexandra Chavarría (executive editor) Paul Arthur (Università del Salento) Margarita Díaz-Andreu (ICREA - Universitat de Barcelona) ADVISORY BOARD José M. Martín Civantos (Universidad de Granada) Martin Carver (University of York) Girolamo Fiorentino (Università del Salento) Matthew H. Johnson (Northwestern University of Chicago) Caterina Giostra (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Milano) Giuliano Volpe (Università degli Studi di Foggia) Susanne Hakenbeck (University of Cambridge) Marco Valenti (Università degli Studi di Siena) Vasco La Salvia (Università degli Studi G. D’Annunzio di Chieti e Pescara) Bastien Lefebvre (Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès) ASSISTANT EDITOR Alberto León (Universidad de Córdoba) Tamara Lewit (Trinity College - University of Melbourne) Francesca Benetti Federico Marazzi (Università degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa di Napoli) LANGUAGE EDITOR Dieter Quast (Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz) Andrew Reynolds (University College London) Rebecca Devlin (University of Louisville) Mauro Rottoli (Laboratorio di archeobiologia dei Musei Civici di Como) Tim Penn (University of Edinburgh) Colin Rynne (University College Cork) Post-Classical Archaeologies (PCA) is an independent, international, peer-reviewed journal devoted to the communication of post-classical research. PCA publishes a variety of manuscript types, including original research, discussions and review ar- ticles. Topics of interest include all subjects that relate to the science and practice of archaeology, particularly multidiscipli- nary research which use specialist methodologies, such as zooarchaeology, paleobotany, archaeometallurgy, archaeome- try, spatial analysis, as well as other experimental methodologies applied to the archaeology of post-classical Europe. -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath. -

The Masonry Bridges in Southern Italy: Vestige to Be Preserved

The masonry bridges in Southern Italy: vestige to be preserved M. Lippiello Second University of Naples, Department of Civil Engineering, Aversa,(CE),Italy L. Bove, L. Dodaro and M.R. Gargiulo University of Naples, Department of Constructions and Mathematical Methods in Architecture, Naples, Italy ABSTRACT: A previous work, “The Stone bridges in Southern Italy: from the Roman tradition to the Middle XIX century”, presented during the Arch Bridges IV, underlined the connection between bridge construction and street network. With the fall of the Roman Empire and the consequent breaking up of the territory into small free states, road construction was no longer a priority and many suburban bridges were abandoned as well. This survey focuses on the Sannio area. It will take into account the following: − ancient bridges still on use; − bridges of Samnite’ Age, adapted in the later centuries, nowadays in a marginal rule with respect to the roads net; − bridges cut off from the road system. The aim of this paper is to describe some of these structures and thereby propose a cataloguing methodology of structural, technologic and material aspects of masonry bridges. The planned methodology’s ultimate purpose is to preserve adequate evidence of this heritage and lay the foundations for its safeguarding in case, future sensibility towards these constructions will not depend exclusively on their utilization. 1 INTRODUCTION Located at about 80 Km N-NW from Naples, the Roccamonfina volcanic pile, extinct in pro- tohistoric era, divides the area in two ambits which differ not only from a geographic but also from a cultural point of view. -

Review of Ancient Wisdom of Qanat, and Suggestions for Future Water Management

Environ. Eng. Res. 2013 June,18(2) : 57-63 Review Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4491/eer.2013.18.2.057 pISSN 1226-1025 eISSN 2005-968X Review of Ancient Wisdom of Qanat, and Suggestions for Future Water Management Mohsen Taghavi-Jeloudar1†, Mooyoung Han1, Mohammad Davoudi2, Mikyeong Kim1 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742, Korea 2Department of River Management, Research Institute for Water Scarcity and Drought, Tehran 13445-1136, Iran Abstract Arid areas have a significant problem with water supply due to climate change and high water demand. More than 3,000 years ago, Persians started constructing elaborate tunnel systems called Qanat for extracting groundwater for agriculture and domestic usages in arid and semi-arid areas and dry deserts. In this paper, it has been demonstrated that ancient methods of water management, such as the Qanat system, could provide a good example of human wisdom to battle with water scarcity in a sustainable manner. The purpose of this paper is twofold: Review of old wisdom of Qanat—to review the history of this ancient wisdom from the beginning until now and study the Qanat condition at the present time and to explore why (notwithstanding that there are significant advantages to the Qanat system), it will no longer be used; and suggestions for future water management—to suggest a number of new methods based on new materials and technology to refine and protect Qanats. With these new suggestions it could be possible to refine and reclaim this method of extracting water in arid areas. -

1 ROMANS CHANGED the MODERN WORLD How The

1 ROMANS CHANGED THE MODERN WORLD How the Romans Changed the Modern World Nick Burnett, Carly Dobitz, Cecille Osborne, Nicole Stephenson Salt Lake Community College 2 Romans are famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments, although some of their own inventions were improvements on older ideas, concepts and inventions. Technology to bring running water into cities was developed in the east, but was transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. Romans also made amazing engineering feats in other every day things such as roads and architecture. Their accomplishments surpassed most other civilizations of their time, and after their time, and many of their structures have withstood the test of time to inspire others. Their feats were described in some detail by authors such as Vitruvius, Frontinus and Pliny the Elder. Today our bridges look complex and so thin that one may think it cannot hold very much weight without breaking or falling apart, but they can. Even from the very beginning of building bridges, they have been made so many times that we can look at different ways to make the bridge less bulky and in the way, to one that is very sturdy and even looks like artwork. What allows an arch bridge to span greater distances than a beam bridge, or a suspension bridge to stretch over a distance seven times that of an arch bridge? The answer lies in how each bridge type deals with the important forces of compression and tension. Tension: What happens to a rope during a game of tug-of-war? It undergoes tension from the two opposing teams pulling on it. -

7Th ROMAN BRIDGES on the LOWER PART of the DANUBE

th 7 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE Contemporary achievements in civil engineering 23-24. April 2019. Subotica, SERBIA ROMAN BRIDGES ON THE LOWER PART OF THE DANUBE Isabella Floroni Andreia-Iulia Juravle UDK: 904:624.21"652" DOI: 10.14415/konferencijaGFS2019.015 Summary: The purpose of the paper is to present the Roman bridges built across the Romanian natural border, the Danube, during the Roman Empire expansion. Some of these are less known than the famous Traian’s bridge in Drobeta Turnu Severin. The construction of bridges on the lower part of the Danube showed the importance of conquering and administrating the ancient province of Dacia. The remaining evidences prove the technical solutions used by the Roman architects at a time when public works had developed. Keywords: Danube bridges, pontoon bridge, Bridge of Constantine the Great, Columna Traiana 1. INTRODUCTION The Danube1 was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire, and today flows through 10 countries, more than any other river in the world. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for 2,850 km, passing through or bordering Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova and Ukraine before draining into the Black Sea. Romania has the longest access to the river, around 1075 km, of which 225 km on Romanian territory exclusively. | CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE (2019) | 189 7. МЕЂУНАРОДНА КОНФЕРЕНЦИЈА Савремена достигнућа у грађевинарству 23-24. април 2019. Суботица, СРБИЈА Fig. 1 Map of the main course of the Danube During the Roman Empire many wooden or masonry bridges were built, some of which lasted longer, other designed for ephemeral military expeditions. -

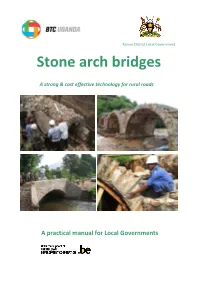

Manual Stone Arch Bridges

Kasese District Local Government Stone arch bridges A strong & cost effective technology for rural roads A practical manual for Local Governments Foreword This manual was developed based on the experience of the Belgian Technical Cooperation (BTC) supported Kasese District Poverty Reduction Programme (KDPRP) in Western Uganda, during the period 2009- 2013. The programme piloted stone arch culverts and bridges in rural areas, where low Table of contents labour costs and high cost of industrial building materials favour this technology. The 1. Chapter 1: Introduction to stone arch bridges .............................. 2 construction of stone arch bridges in Uganda, 1.1 Background and justification. ...................................................... 2 Tanzania & Rwanda has demonstrated its 1.2 The stone arch bridge technology ............................................... 3 overall feasibility in East Africa. 1.3 Advantages & limitations. ........................................................... 5 1.4 Stone arch bridges: implications of labour-based technology. ... 7 How to use this manual 2. Chapter Two: Design of stone arch bridges ................................... 8 The purpose of this manual is to provide 2.1 Quick scan – site assessment ...................................................... 8 supervisors of stone arch bridge works with 2.2 Planning and stakeholders involved. ........................................... 9 an easy step by step guide. The stepwise 2.3 Design ......................................................................................... -

Touchdown in the Haert of Romance!

Arvidsjaur Reykjavik enchanting Trier Tampere Oslo Stockholm Mainz Glasgow Göteborg you! Koblenz Dublin Riga Kerry Kaunas Kaiserslautern London Gdansk Minsk Speyer Frankfurt-Hahn Wroclaw Katowice Worms Santiago de Bratislava Compostela Budapest Biarritz Verona Balaton Santander Milan Venice Porto Montpellier Bologna Madrid Reus Pisa Gerona Faro Jerez de la Pescara Frontera Valencia Rome Bari Majorca Alghero Malaga Granada Fès Marrakech Tenerife Fuerteventura Touchdown in the heart of Romance! Only one hour to castles, kings, Kaisers and the beautiful Loreley We welcome you to the Central Rhine Valley, designated as a Unesco World Cultural Heritage site. Enjoy the sights of the region. From the cities of Worms, Speyer, Kaiserslautern, Trier, Koblenz and Mainz, as well as the Rhine and Moselle Valleys, walk in the footsteps of Germany’s history. Some of the country’s most valuable historical treasures are only a short drive away from Frankfurt-Hahn Airport. And once you have had your fi ll, simply take a connection to the next destination: Madrid, Budapest, London or Stockholm perhaps? However, fi rst and foremost: we are glad to have you as our guest! www.hahn-airport.de EV 105x210 4c UK.indd 1 14.12.2007 14:06:43 Uh Trier inviting Mainz you! Koblenz Kaiserslautern Speyer Worms A feeling that goes under your skin... Treat yourself to a holiday of pure romance and full of passion. Six towns in south- west Germany invite you to partake in exciting experiences, creative pleasures and unforgettable memories. The romantic cities of Trier, Koblenz, Mainz, Worms, Speyer and Kaiserslautern – all boasting a wealth of history, all situated along the Rhine and Moselle rivers and all of them marked by legendary castles and palaces, mighty cathedrals and churches, crooked old streets and modern shopping arcades, alluring culinary specialities and world-famous wines.