Author's Introduction to the Selected Works of Karl Andreas Taube

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

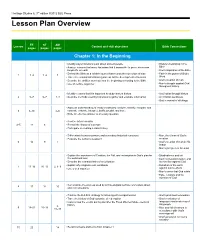

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Mayan Indigenous Society in Guatemala and Mexico: a Thematic Integrated Unit on the Contributions of the Maya Both Past and Present

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 449 078 SO 032 443 AUTHOR Suchenski, Michelle TITLE Mayan Indigenous Society in Guatemala and Mexico: A Thematic Integrated Unit on the Contributions of the Maya Both Past and Present. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 2000 (Mexico and Guatemala). SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 62p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; Cultural Context; *Curriculum Development; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; Intermediate Grades; *Maya (People); *Mayan Languages; *Social Studies; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Guatemala; Historical Background; Mayan Civilization; *Mexico ABSTRACT This curriculum unit focuses on the contributions of the ancient Mayan people and how these contributions have been interwoven with contemporary society. The unit is divided into the following sections: (1) "Preface"; (2) "Mayan Civilization" (geography); (3) "Mayan Contributions" (written language); (4) "Mayan Contributions" (textiles); (5) "Mayan Textiles" (literature selection: "Abuela's Weave"); (6) "Mayan Influence in Guatemala and Mexico"; (7) "Mayan Contributions" (mathematics); (8) "Appendix"; and (9)"Sources Consulted." Lessons include standards, essential skills, historical background, vocabulary, procedures, materials, questions, background notes, map work, and quizzes. (BT) POOR PRINT MALI Pgs Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. MAYAN INDIGENOUS SOCIETY IN GUATEMALA AND MEXICO: A THEMATIC INTEGRATED UNIT ON THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE MAYA BOTH PAST AND PRESENT PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION BEEN GRANTED BY CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization /riginating it. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

Religious Advisement Resources Part Ii

RELIGIOUS ADVISEMENT RESOURCES 2020 PART II Notice Regarding External Resources: The listed resources are provided in this document are operated by other government organizations, commercial firms, educational institutions, and private parties. We have no control over the information of these resources which may contain information that could be objectionable or which may not otherwise conform to Department of Defense policies. These listings are offered as a convenience and for informational purposes only. Their inclusion here does not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the Department of Defense of any of the products, services, or opinions of the external providers. The Department of Defense bears no responsibility for the accuracy or the content of these resources. 1 FAITH AND BELIEF SYSTEMS U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Prisons Inmate Religious Beliefs and Practices http://www.acfsa.org/documents/dietsReligious/FederalGuidelinesInmateReligiousBeliefsandPractices032702.pdf Buddhism Native American Eastern Rite Catholicism Odinism/Asatru Hinduism Protestant Christianity Islam Rastfari Judaism Roman Catholic Christianity Moorish Science Temple of America Sikh Dharma Nation of Islam Wicca U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Religious Literacy Primer https://crcc.usc.edu/files/2015/02/Primer-HighRes.pdf Baha’i Earth-Based Spirituality Buddhism Hinduism Christianity: Anabaptist Humanism Anglican/Episcopal Islam Christian Science Jainism Evangelical Judaism Jehovah’s Witnesses -

THE GREAT MAYAN ECLIPSE: Yucatán México October 14, 2023

Chac Mool, Chichén Itzá Edzna Pyramid, Campeche THE GREAT MAYAN ECLIPSE: Yucatán México October 14, 2023 October 6-16, 2023 Cancún • Chichén-Itzá • Mérida • Campeche On October 14, 2023, a ‘ring of fire’ Annular Solar Eclipse will rip across the western U.S. and parts of the Yucatán in México as well as Central and South America. Offer your members the opportunity to see a spectacular annular eclipse among the ruins of the mighty Maya civilization. Meet in Cancún before heading off to Chichén Itzá, Ek Balam, Uxmal, Mérida, and Campeche. On Eclipse Day transfer to our viewing site outside Campeche in the vicinity of the Maya Site of Edzná to see this spectacular annular solar eclipse. Here passengers can see a smaller-than-usual moon fit across 95% of the sun to leave a ring of fire. The ring of fire will reign for 4 minutes and 31 seconds while very high in the darkened sky. Highlights • Swim in a cenote or sinkhole formed million years ago from a colossal asteroid impact to the region. • Enjoy a stay at a luxury and historic hacienda. • Investigate the UNESCO Heritage Sites of Chichén Itzá one of the “New 7 Wonders of the World.” • Witness the ring of fire of an Annular clipseE near the Maya ruins. Itinerary 2023 Oct 06: U.S. / Cancún Oct 08: Chichén Itzá Fly to Cancún. Transfer to hotel near the airport. Meet in the Private sunrise tour of Chichén Itzá before it opens to the public. early evening at the reception area for a briefing of tomorrow’s The site contains massive structures including the immense El departure. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

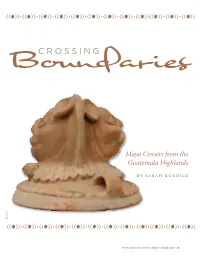

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Robert M. Rosenswig

FAMSI © 2004: Robert M. Rosenswig El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco Traducido del Inglés por Alex Lomónaco Año de Investigación: 2002 Cultura: Olmeca Cronología: Pre-Clásico Ubicación: Soconusco, Chiapas, México Sitio: Cuauhtémoc Tabla de Contenidos Introducción El Proyecto Formativo Soconusco 2002 Análisis en curso Conclusion Lista de Figuras Referencias Citadas Entregado el 6 de septiembre del 2002 por: Robert M. Rosenswig Department of Anthropology Yale University [email protected] Introducción El sitio de Cuauhtémoc está ubicado dentro de una zona del Soconusco que no ha sido documentada con anterioridad y que se encuentra entre las organizaciones estatales del Formativo Temprano de Mazatlán (Clark y Blake 1994), el centro del Formativo Medio de La Blanca (Love 1993) y el centro del Formativo Tardío de Izapa (Lowe et al. 1982) (Figura 1). Aprovechando la refinada cronología del Soconusco (Cuadro 1), el trabajo de campo que se describe a continuación aporta datos que permiten rastrear el desarrollo de Cuauhtémoc durante los primeros 900 años de vida de asentamiento en Mesoamérica. Este período de tiempo está dividido en siete fases cerámicas, y de esta forma, permite que se rastreen, prácticamente siglo por siglo, los cambios ocurridos en todas las clases de cultura material. Estos datos están siendo utilizados para documentar el surgimiento y el desarrollo de las complejidades sociopolíticas en el área. Además de los procesos locales, el objetivo de esta investigación es determinar la naturaleza de las relaciones cambiantes entre las élites de la Costa del Golfo de México y el Soconusco. El trabajo también apunta a ser significativo en lo que respecta a cruzamientos culturales, dado que Mesoamérica es sólo una entre un puñado de áreas del mundo donde la complejidad sociopolítica surgió independientemente, y el Soconusco contiene algunas de las sociedades más tempranas en las que esto ocurrió (Clark y Blake 1994; Rosenswig 2000). -

Cacao Use and the San Lorenzo Olmec

Cacao use and the San Lorenzo Olmec Terry G. Powisa,1, Ann Cyphersb, Nilesh W. Gaikwadc,d, Louis Grivettic, and Kong Cheonge aDepartment of Geography and Anthropology, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA 30144; bInstituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico 04510; cDepartment of Nutrition and dDepartment of Environmental Toxicology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; and eDepartment of Anthropology, Trent University, Peterborough, ON, Canada K9J 7B8 Edited by Michael D. Coe, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved April 8, 2011 (received for review January 12, 2011) Mesoamerican peoples had a long history of cacao use—spanning Selection of San Lorenzo and Loma del Zapote Pottery Samples. The more than 34 centuries—as confirmed by previous identification present study included analysis of 156 pottery sherds and vessels of cacao residues on archaeological pottery from Paso de la Amada obtained from stratified deposits excavated under the aegis of on the Pacific Coast and the Olmec site of El Manatí on the Gulf the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Archaeological Project (SLTAP). Coast. Until now, comparable evidence from San Lorenzo, the pre- Items selected represented Early Preclassic occupation contexts mier Olmec capital, was lacking. The present study of theobromine at two major Olmec sites, San Lorenzo (n = 154) and Loma del residues confirms the continuous presence and use of cacao prod- Zapote (n = 2), located in the lower Coatzacoalcos drainage ucts at San Lorenzo between 1800 and 1000 BCE, and documents basin of southern Veracruz State, Mexico (Fig. 1). Sample se- assorted vessels forms used in its preparation and consumption. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923).