An Iranian Perspective Masoud Mohammadirad, Mohammad Rasekh-Mahand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish As

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish as Spoken in Turkey 1. Special handling of dialects Kurmanji Kurdish is a major branch of modern Kurdish, which belongs to the Iranian group of languages. Kurdish is largely a spoken language with a limited but growing body of modern literature. There are many dialectal varieties of Kurdish spread over a wide area of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Armenia and Azerbaijan. There are, in addition, different classifications of Kurdish languages and Kurdish peoples that align dialectal choice with tribal affinity. Linguistic and Kurdish scholars usually describe modern Kurdish as having two closely related major branches: Kurmanji (the northern branch) and Sorani (the southern branch). They are not mutually intelligible (see Thackston (2006) p. vii). The Kurdish Institute summarizes the situation as follows: “Kurdish has two regional standards, namely Kurmanji in Turkey, and Sorani farther east and south. Roughly half of Kurdish speakers live in Turkey.” (see http://www.institutkurde.org/en/ and also http://www.blueglobetranslations.com/about- kurdish-kurmanji-language.html). Within the larger region there are two other languages often associated with ethnic Kurds. These are Dimili (also known as Zazaki) and Gorani. Although sometimes classified as sub-dialects of Kurdish (e.g., Kurdish Language - Britannica Online Encyclopedia), these languages belong to a different group of Iranian languages (see for example, http://kurds_history.enacademic.com/346/Kurmanji). Although Kurmanji Kurdish is spoken across a range of countries, it has the advantage of being spoken by around 60-80% of Kurds and is considered a regional standard. The majority of Kurmanji speakers live in Turkey, making it the ideal country for collection of audio data (see for example, http://linguakurd.blogfa.com/post-106.aspx). -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-Standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik ABSTRACT The article aims to introduce a gold-standard Pashto dataset and a segmentation app. The Pashto dataset consists of 300 line images and corresponding Pashto text from three selected books. A line image is simply an image consisting of one text line from a scanned page. To our knowledge, this is one of the first open access datasets which directly maps line images to their corresponding text in the Pashto language. We also introduce the development of a segmentation app using textbox expanding algorithms, a different approach to OCR segmentation. The authors discuss the steps to build a Pashto dataset and develop our unique approach to segmentation. The article starts with the nature of the Pashto alphabet and its unique diacritics which require special considerations for segmentation. Needs for datasets and a few available Pashto datasets are reviewed. Criteria of selection of data sources are discussed and three books were selected by our language specialist from the Afghan Digital Repository. The authors review previous segmentation methods and introduce a new approach to segmentation for Pashto content. The segmentation app and results are discussed to show readers how to adjust variables for different books. Our unique segmentation approach uses an expanding textbox method which performs very well given the nature of the Pashto scripts. The app can also be used for Persian and other languages using the Arabic writing system. The dataset can be used for OCR training, OCR testing, and machine learning applications related to content in Pashto. -

Current Issues in Kurdish Linguistics Current Issues in Kurdish Linguistics 1 Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics

Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics 1 Songül Gündoğdu, Ergin Öpengin, Geofrey Haig, Erik Anonby (eds.) Current issues in Kurdish linguistics Current issues in Kurdish linguistics 1 Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Bamberg Studies in Kurdish Linguistics Series Editor: Geofrey Haig Editorial board: Erik Anonby, Ergin Öpengin, Ludwig Paul Volume 1 2019 Current issues in Kurdish linguistics Songül Gündoğdu, Ergin Öpengin, Geofrey Haig, Erik Anonby (eds.) 2019 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Diese Veröff entlichung wurde im Rahmen des Elite-Maststudiengangs „Kul- turwissenschaften des Vorderen Orients“ durch das Elitenetzwerk Bayern ge- fördert, einer Initiative des Bayerischen Staatsministeriums für Wissenschaft und Kunst. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröff entlichung liegt bei den Auto- rinnen und Autoren. Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über das Forschungsinformations- system (FIS; https://fi s.uni-bamberg.de) der Universität Bamberg erreichbar. Das Werk – ausgenommen Cover, Zitate und Abbildungen – steht unter der CC-Lizenz CC-BY. Lizenzvertrag: Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. Herstellung und Druck: Digital Print Group, Nürnberg Umschlaggestaltung: University of Bamberg Press © University of Bamberg Press, Bamberg 2019 http://www.uni-bamberg.de/ubp/ ISSN: 2698-6612 ISBN: 978-3-86309-686-1 (Druckausgabe) eISBN: 978-3-86309-687-8 (Online-Ausgabe) URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:473-opus4-558751 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20378/irbo-55875 Acknowledgements This volume contains a selection of contributions originally presented at the Third International Conference on Kurdish Linguistics (ICKL3), University of Ams- terdam, in August 2016. -

NACIL. Sorani Pptx

Identity Avoidance in Morphology; Evidence from Polyfunctional Clitics of Sorani Kurdish Sahar Taghipour University of Kentucky April 2017 In this study ´ Kurdish and its dialects In this study ´ Kurdish and Its Dialects ´ Polyfunctional Clitics in Sorani Kurdish In this study ´ Kurdish and its dialects ´ Polyfunctional Clitics in Sorani Kurdish ´ Morphological Haplology In this study ´ Kurdish and its dialects ´ What are the polyfunctional clitics in Sorani Kurdish ´ Morphological Haplology ´ Constraint-based Morphology with basic concepts from Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky: 1993 ) Kurdish and its dialects ´ Iranian languages are divided into two major branches: Western and Eastern Southwestern (Persian) and Northwestern (Kurdish) ´ Kurdish “Is a cover term for a cluster of northwest Iranian languages and dialects spoken by between 20 and 30 million speakers in a contiguous area of West Iran, North Iraq, eastern Turkey and eastern Syria” (Haig and Opengin: 2015) Northern, Central, and Southern(Windfuhr (2009) “In terms of numbers of speakers and degree of standardization, the two most important Kurdish dialects are Sorani (Central Kurdish) and Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish)” (Haig and Matras: 2002) Where Kurdish is spoken? ´ Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji) They’re mainly in Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Western Azarbayjan in Iran ´ Central Kurdish (Sorani or Mukri) Some parts in Iraq and Iran (Northwestern, Northeastern, in particular ) ´ Southern Kermanshah and Ilam Province (West and Southwestern part of Iran) Sorani and Its Dialects In this study, I am going to talk in particular about Sorani Kurdish. Its dialects are: Mukriyani Ardalani Garmiani Hawlari Babani Jafi Sorani and Its Dialects In this study, I am going to talk in particular about Sorani Kurdish. -

Pdf 373.11 K

Journal of Language and Translation Volume 11, Number 4, 2021 (pp. 1-18) Adposition and Its Correlation with Verb/Object Order in Taleshi, Gilaki, and Tati Based on Dryer’s Typological Approach Farinaz Nasiri Ziba1, Neda Hedayat2*, Nassim Golaghaei3, Andisheh Saniei4 ¹ PhD Candidate of Linguistics, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran ² Assistant Professor of Linguistics, Varamin-Pishva Branch, Islamic Azad University, Varamin, Iran ³ Assistant Professor of Applied Linguistics, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran ⁴ Assistant Professor of Applied Linguistics, Roudehen Branch, Islamic Azad University, Roudehen, Iran Received: January 6, 2021 Accepted: May 9, 2021 Abstract This paper is a descriptive-analytic study on the adpositional system in a number of northwestern Iranian languages, namely Taleshi, Gilaki, and Tati, based on Dryer’s typological approach. To this end, the correlation of verb/object order was examined with the adpositional phrase and the results were compared based on the aforesaid approach. The research question investigated the correlation between adposition and verb/object order in each of these three varieties. First, the data collection was carried out through a semi-structured interview that was devised based on a questionnaire including a compilation of 66 Persian sentences that were translated into Taleshi, Gilaki, and Tati during interviews with 10 elderly illiterate and semi-literate speakers, respectively, from Hashtpar, Bandar Anzali, and Rostamabad of the Province of Gilan for each variety. Then, the transcriptions were examined in terms of diversity in adpositions, including two categories of preposition and postposition. The findings of the study indicated a strong correlation between the order of verbs and objects with postpositions. -

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1

Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 1 Full title: A perceptual dialectological approach to linguistic variation and spatial analysis of Kurdish varieties Main Author: Eva Eppler, PhD, RCSLT, Mag. Phil Reader/Associate Professor in Linguistics Department of Media, Culture and Language University of Roehampton | London | SW15 5SL [email protected] | www.roehampton.ac.uk Tel: +44 (0) 20 8392 3791 Co-author: Josef Benedikt, PhD, Mag.rer.nat. Independent Scholar, Senior GIS Researcher GeoLogic Dr. Benedikt Roegergasse 11/18 1090 Vienna, Austria [email protected] | www.geologic.at Short Title: Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish Perceptual Dialectology and GIS in Kurdish 2 Abstract: This paper presents results of a first investigation into Kurdish linguistic varieties and their spatial distribution. Kurdish dialects are used across five nation states in the Middle East and only one, Sorani, has official status in one of them. The study employs the ‘draw-a-map task’ established in Perceptual Dialectology; the analysis is supported by Geographical Information Systems (GIS). The results show that, despite the geolinguistic and geopolitical situation, Kurdish respondents have good knowledge of the main varieties of their language (Kurmanji, Sorani and the related variety Zazaki) and where to localize them. Awareness of the more diverse Southern Kurdish varieties is less definitive. This indicates that the Kurdish language plays a role in identity formation, but also that smaller isolated varieties are not only endangered in terms of speakers, but also in terms of their representations in Kurds’ mental maps of the linguistic landscape they live in. Acknowledgments: This work was supported by a Santander and by Ede & Ravenscroft Research grant 2016. -

A Systematic Ornithological Study of the Northern Region of Iranian Plateau, Including Bird Names in Native Language

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library European Journal of Experimental Biology, 2012, 2 (1):222-241 ISSN: 2248 –9215 CODEN (USA): EJEBAU A systematic ornithological study of the Northern region of Iranian Plateau, including bird names in native language Peyman Mikaili 1, (Romana) Iran Dolati 2,*, Mohammad Hossein Asghari 3, Jalal Shayegh 4 1Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran 2Islamic Azad University, Mahabad branch, Mahabad, Iran 3Islamic Azad University, Urmia branch, Urmia, Iran 4Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture and Veterinary, Shabestar branch, Islamic Azad University, Shabestar, Iran ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT A major potation of this study is devoted to presenting almost all main ornithological genera and species described in Gilanprovince, located in Northern Iran. The bird names have been listed and classified according to the scientific codes. An etymological study has been presented for scientific names, including genus and species. If it was possible we have provided the etymology of Persian and Gilaki native names of the birds. According to our best knowledge, there was no previous report gathering and describing the ornithological fauna of this part of the world. Gilan province, due to its meteorological circumstances and the richness of its animal life has harbored a wide range of animals. Therefore, the nomenclature system used by the natives for naming the animals, specially birds, has a prominent stance in this country. Many of these local and dialectal names of the birds have been entered into standard language of the country (Persian language). The study has presented majority of comprehensive list of the Gilaki bird names, categorized according to the ornithological classifications. -

THE PHONOLOGY of the VERBAL PHRASE in HINDKO Submitted By

THE PHONOLOGY OF THE VERBAL PHRASE IN HINDKO submitted by ELAHI BAKHSH AKHTAR AWAN FOR THE AWARD OF A DEGREE OF Ph.D. at the UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1974 ProQuest Number: 10672820 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672820 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 acknowledgment I wish to express my profound sense of gratitude and indebtedness to my supervisor Dr. R.K. Sprigg. But for his advice, suggestions, constructive criticism and above all unfailing kind ness at all times this thesis could not have been completed. In addition, I must thank my wife Riaz Begum for her help and encouragement during the many months of preparation. CONTENTS Introduction i Chapter I Value of symbols used in this thesis 1 1 .00 Introductory 1 1.10 I.P.A. Symbols 1 1.11 Other symbols 2 Chapter II The Verbal Phrase and the Verbal Word 6 2.00 Introductory 6 2.01 The Sentence 6 2.02 The Phrase 6 2.10 The Verbal Phra.se 7 2.11 Delimiting the Verbal Phrase 7 2.12 Place of the Verbal Phrase 7 2.121 -

A Study of Common Expressions in English and Farsi Languages and Their Equivalents in Gilaki Dialect in North of Iran

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.comISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 17:4 April 2017 ================================================================= A Study of Common Expressions in English and Farsi languages and Their Equivalents in Gilaki Dialect in North of Iran Mohammad Kazemian Sana'ati, Ph.D. Candidate in TEFL Farhad Passandyar, Ph.D. Candidate in TEFL Davood Mashadi Heidar Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon Branch, Tonekabon, Iran ======================================================================== Abstract The Gilaki dialect belongs to the north-western group of Iranian languages. The Gilaki dialect is spread along the southern shore of the Caspian Sea in one of the northern provinces of Iran known as Guilan. The native speakers of the language call themselves Gilaks and their dialect Gilaki. In Guilan province, Gilaki is the vernacular language of some three million people mostly born in central and eastern Guilan province. The present study focuses on the commonalities in expressions used in English, Farsi and Gilaki. To conduct the study, 50 people from all walks of life from Langroud, Eastern Guilan, were interviewed. The expressions uttered in Gilaki were then analyzed and compared in meaning with their nearest equivalents in English and Farsi languages. The study showed that Gilaki satisfied the criteria necessary to be considered a language rather than a dialect. Keywords: Guilan, Gilaks, and Gilaki expressions 1. Introduction Guilan province lies along the Caspian Sea, west of Mazandaran Province, east of Ardabil Province, and north of Zanjan and Qazvin Provinces in Iran. Moreover, it borders the Republic of Azerbaijan in the north and Russia across the Caspian Sea. According to Kiyafar (2013,P. 11), "Guilan is very rich culture dates back to 7000 years ago. -

Book Reviews Mélanges D'ethnographie Et De

Iran and the Caucasus 22 (2018) 419-422 Book Reviews Mélanges d’ethnographie et de dialectologie Irano-Aryennes à la mémoire de Charles-Martin Kieffer (Studia Iranica, Cahier 61), edited by Matteo De Chiara, Adriano V. Rossi, and Daniel Septfonds, Leuven: “Peeters”, 2018.— 413 pp. + map. The volume is dedicated to the memory of Charles-Martin Kieffer, the prominent French linguist and ethnographer on matters Afghanica. Kief- fer’s fundamental contribution to the Atlas Linguistique de l’Afghanistan, the description of two critically endangered Iranian languages (Ōrmuṛi of Baraki-Barak and Parāči), as well as data on language taboos in Afghan countryside, remain crucial for the research on Afghan ethnography and socio-linguistic situation in Afghanistan. The range of the topics of sixteen articles collected in Kieffer’s homage is wide enough to include contributions on Ossetic funeral rites and Balo- chi war-ballads, influence of Pashto on Dardic languages of Afghanistan and prefixes in Ormuri, etc. L. Arys in “Les Rites Funéraires Ossètes”, highlights the archaic charac- ter of the funerary customs among the Iranian-speaking Ossetes in the Caucasus and shows how this tradition is still important for a contempo- rary Ossete family. S. Badalkhan (“A Balochi Ballad on the Brāhō-Jadgāl Wars and the formation of Brāhōī Tribes”) presents a piece from the rich Balochi oral tradition, a 17th century ballad recounting the tribal confrontation and clashes between multilingual (Balochi, Jadgali, Brahoi) units in Kalat and Khuzdar districts, which led to the formation of Brahoi tribes based on heterogenous elements. H. Borjian’s article, “The Dialect of Khur”, is a skectch of the grammar of a largely understudied dialect of Biabanak district at the southern bor- der of Dasht-e Kavir desert in Iran. -

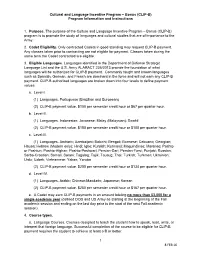

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions 1. Purpose. The purpose of the Culture and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) program is to promote the study of languages and cultural studies that are of importance to the Army. 2. Cadet Eligibility. Only contracted Cadets in good standing may request CLIP-B payment. Any classes taken prior to contracting are not eligible for payment. Classes taken during the same term the Cadet contracted are eligible. 3. Eligible Languages. Languages identified in the Department of Defense Strategic Language List and the U.S. Army ALARACT 236/2013 provide the foundation of what languages will be authorized for CLIP-B payment. Commonly taught and known languages such as Spanish, German, and French are dominant in the force and will not earn any CLIP-B payment. CLIP-B authorized languages are broken down into four levels to define payment values. a. Level-I. (1) Languages. Portuguese (Brazilian and European) (2) CLIP-B payment value. $100 per semester credit hour or $67 per quarter hour. b. Level-II. (1) Languages. Indonesian; Javanese; Malay (Malaysian); Swahil (2) CLIP-B payment value. $150 per semester credit hour or $100 per quarter hour. c. Level-III. (1) Languages. Amharic; Azerbaijani; Baluchi; Bengali; Burmese; Cebuano; Georgian; Hausa; Hebrew (Modern only); Hindi; Igbo; Kurdish; Kurmanji; Maguindinao; Maranao; Pashto or Pashtun; Pashto-Afghan; Pashto-Peshwari; Persian-Dari; Persian-Farsi; Punjabi; Russian; Serbo-Croatian; Somali; Sorani; Tagalog; Tajik; Tausug; Thai; Turkish; Turkmen; Ukrainian; Urdu; Uzbek; Vietnamese; Yakan; Yoruba (2) CLIP-B payment value. $200 per semester credit hour or $134 per quarter hour.