Overview Section: Infrastructure Essential Services in Need of Attention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clovis Municipal Airport

Clovis Municipal Airport BAirportigBear MasterCityAi Planrport Master Plan Planning Services BigBearCityAirport Master Plan Planning Services Prepared by: In association with AIRPORT MASTER PLAN for Clovis Municipal Airport Clovis, New Mexico Prepared for City of Clovis, New Mexico by KSA, Inc. in association with CDM Smith, Inc. DRAFT FINAL September 2015 The preparation of this document was financially support, in part, through a grant provided by the New Mexico Department of Transportation. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the NMDOT or Federal Aviation Administration. Acceptance of this report by the NMDOT or FAA does not in any way constitute a commitment on the part of the State of New Mexico or United States to participate in any development depicted therein nor does it indicate that the proposed development is environmentally acceptable or would have justification in accordance with appropriate public laws. PLAN Table of Contents Chapter One: Inventory of Existing Conditions 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Overview of the Airport .......................................................................... 1-2 1.2.1 CVN Location .................................................................................1-2 1.2.2 CVN Sponsor Management ..............................................................1-4 1.2.3 CVN History ....................................................................................1-5 -

Appendix 1 Documentary Sources for Overland Trails

APPENDIX 1 DOCUMENTARY SOURCES ON OVERLAND TRAILS Prepared by the Mapping and Marking Committee Fifth Edition (Revised and Expanded) June 2014 Published by the Oregon-California Trails Association P.O. Box 1019 Independence, MO 64051-0519 816-252-2276 [email protected] www.octa-trails.org © Copyright 1993,1994,1996,2002, 2014 By Oregon-California Trails Association All Rights Reserved (This page intentionally blank) DOCUMENTARY SOURCES ON OVERLAND TRAILS Emigrant trail literature of all types is the primary documentary resource available to the trail researcher. Fortunately, knowledge of and access to this trail literature is becoming more readily available. For the researcher, it’s a process of identifying and locating desirable emigrant documents, then utilizing them by following the research procedures recommended in the MET Manual. The more knowledge trail researchers have of trail literature, the easier the task and the more effective fieldwork becomes. If detailed enough, emigrant diaries and journals—eyewitness accounts of trails—provide the most reliable documentary evidence for trail research and field verification. A number of standard, published bibliographies on emigrant overland travel are readily available for various emigrant trails. For brevity, only the authors/editors, titles, and publication years are given. On the northern routes see: Merrill J. Mattes, Platte River Road Narratives: A Descriptive Bibliography of Travel Over the Great Central Overland Route to Oregon, California, Utah, Colorado, Montana, and Other Western States and Territories, 1812–1866 (1988). John M. Townley, The Trail West: A Bibliography – Index to Western American Trails, 1841– 1869 (1988). Lannon W. Mintz, The Trail: A Bibliography of the Travelers on the Overland Trail to California, Oregon, Salt Lake City, and Montana during the Years 1841–1864 (1987) Marlin L. -

Alamogordo-White Sands Regional Airport

AIRPORT MASTER PLAN UPDATE For The Alamogordo-White Sands Regional Airport PREPARED FOR THE City of Alamogordo SUBMITTED BY URS Corporation TECHNICAL REPORT ALAMOGORDO-WHITE SANDS REGIONAL AIRPORT, AIRPORT MASTER PLAN UPDATE Prepared for: City of Alamogordo Jim Talbert, Airport Coordinator City of Alamogordo 3500 AIRPORT ROAD ALAMOGORDO, NM 88310 Telephone: (575) 439-4110 http://ci.alamogordo.nm.us/coa/communityservices/Airport.htm Prepared by: URS Corporation Bill Griffin - Principal-in-Charge Andy Herman - Senior Airport Planner Amy Davis - Airport Civil Engineer July 2014 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Highway Administration, and the Aviation Division, New Mexico Department of Transportation. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration, Federal Highway Administration, and the Aviation Division, New Mexico Department of Transportation. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE - INVentorY ......................................................................................................1-1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE .....................................................................................................................1-1 BACKGROUND ..............................................................................................................................1-2 -

Wagons, Echo Canyon, Ca. 1868. Courtesy LDS Church Archives. Mormon Emigration Trails Stanley B

Wagons, Echo Canyon, ca. 1868. Courtesy LDS Church Archives. Mormon Emigration Trails Stanley B. Kimball Introduction We are in the midst of an American western trails renaissance. Interest in historic trails has never been higher. There is an annual, quarterly, almost monthly increase in the number of books, guides, bib liographies, articles, associations, societies, conferences, symposia, centers, museums, exhibits, maps, dramatic presentations, videos, fes tivals, field trips, trail-side markers and monuments, grave sites, trail signing, and other ventures devoted to our western trail heritage. 1 In 1968, Congress passed the National Trails System Act and in 1978 added National Historic Trail designations. Since 1971 at least fif teen major federal studies of the Mormon Trail have been made.2 So much is going on that at least half a dozen newsletters must be pub lished to keep trail buffs properly informed. Almost every newsletter records the discovery of new trail ruts and artifacts-for example, the recent discovery of some ruts on the Woodbury Oxbow-Mormon Trail in Butler County, Nebraska, and new excavations regarding the Mor mon occupation of Fort Bridger. Hundreds of trail markers with text, many referring to the Mor mons, line the western trails. These markers have been placed by many federal, state, county, municipal, and private associations, including the Bureau of Land Management; Daughters of the American Revolution; Daughters of Utah Pioneers (who alone have placed more than 465 his torical markers); Sons of Utah Pioneers; Utah Pioneer Trails and Land marks; the Boy Scouts; the Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Kansas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Utah state historical societies; and many county historical societies. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. ___X___ New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Lincoln Highway – Pioneer Branch, Carson City to Stateline, Nevada B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Early Trails and Overland Routes, 1840’s-1863 Early Road Development in Nevada, 1865-1920’s Establishment of the Lincoln Highway and the Pioneer Branch, 1910-1913 Evolution of the Lincoln Highway and the Pioneer Branch, 1914-1957 C. Form Prepared by: name/title Chad Moffett, Dianna Litvak, Liz Boyer, Timothy Smith organization Mead & Hunt, Inc. street & number 180 Promenade Circle, Suite 240 city or town Sacramento state CA zip code 95834 e-mail [email protected] telephone 916-971-3961 date January 2018 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

New Horizons on the Oregon Trail

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: New Horizons on the Oregon Trail Full Citation: Merrill J Mattes, “New Horizons on the Oregon Trail,” Nebraska History 56 (1975): 555-571. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1975OldOregonTrail.pdf Date: 3/30/2016 Article Summary: This article presents the address given by Merrill J Mattes before the Nebraska State Historical Society at Lexington, Nebraska, June 14, 1975. It is primarily a descriptive of the first Bicentennial celebration at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, in April of 1975 and a journey along the Oregon Trail that the presenter had taken. Cataloging Information: Photographs / Images: Merrill J Mattes receiving the 1969 Western Heritage Award in the nonfiction category for his The Great Platte River Road. NEW HORIZONS ON mE OLD OREGON TRAIL By MERRILL J. MATTES Presented at the Spring Meeting of the Nebraska State Historical Society at Lexington, Nebraska, June 14, 1975 This spring meeting of the Nebraska State Historical Society at Lexington is a very special occasion, and I hope my remarks will convey to you why I consider this a red-letter day. -

The Story of Mud Springs

The Story of Mud Springs (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Paul Henderson, “The Story of Mud Springs,” Nebraska History 32 (1951): 108-119 Article Summary: The Scherers, early settlers in western Nebraska, purchased in 1896 the land on which the town of Mud Springs and the site of the old Pony Express station are situated. Once a place of refuge from hostile Indians, the property became an outstanding ranch noted for its hospitality. Cataloging Information: Names: F T Bryan, Thomas Montgomery, William O Collins, William Ellsworth, Mr and Mrs J N Scherer Nebraska Place Names: Mud Springs, Morrill County Keywords: covered wagons, stage coaches, Pony Express, trans-continental telegraph line, Central Overland Route, Ash Hollow, Twenty-Two Mile Ranch, Rouilette & Pringle’s Ranch, McArdle’s Ranch, Jules Ranch (later Julesberg), Union Pacific Railroad Photographs / Images: Mud Springs area map, ground plan and location map of Mud Springs THE STORY OF MUD SPRINGS BY PAUL HENDERSON un Springs, because of the events which took place there in the days of the Covered Wagon Emigration, M has become one of the many "story spots" that dot the way along the old Oregon-California wagon road, a trail that has become almost obliterated except in the non agricultural area of the West. -

Routing Directives Used on Western Mails

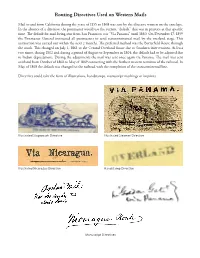

Routing Directives Used on Western Mails Mail to and from California during the years of 1855 to 1868 was sent by the directive written on the envelope. In the absence of a directive, the postmaster would use the current “default” that was in practice at that specific time. The default for mail being sent from San Francisco was “Via Panama” until 1860. On December 17, 1859 the Postmaster General instructed all postmasters to send transcontinental mail by the overland stage. This instruction was carried out within the next 2 months. The preferred method was the Butterfield Route through the south. This changed on July 1, 1861 to the Central Overland Route due to Southern interventions. At least two times, during 1862 and during a period of August to September in 1864, the default had to be adjusted due to Indian depredations. During the adjustments the mail was sent once again via Panama. The mail was sent overland from October of 1868 to May of 1869 connecting with the farthest western terminus of the railroad. In May of 1869 the default was changed to the railroad with the completion of the transcontinental line. Directives could take the form of illustrations, handstamps, manuscript markings or imprints. Illustrated Stagecoach Directive Illustrated Steamer Directive Illustrated Nicaragua Directive Handstamp Directive Manuscript Directives Via Panama - Directives Mail was carried by the US Mail Steamship Co. (between NY and Chagres) and the Pacific Mail Steamship Co (between Panama and San Francisco). Carriage across the isthmus of Panama was by railroad. This was the default method of mail carriage until December 17, 1859. -

Utah Mail Service Before the Coming of the Railroad, 1869

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1957 Utah Mail Service Before the Coming of the Railroad, 1869 Ralph L. McBride Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation McBride, Ralph L., "Utah Mail Service Before the Coming of the Railroad, 1869" (1957). Theses and Dissertations. 4921. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4921 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. UTAH MAIL SERVICE EFOREBEFOREB THE COMING OF vitthevicTHS RAILROAD 1869 A ttiftistheftsthefisSUBMITTEDSUWATTTED TO THE department OF HISTORY OF BRIGHAMBRIGITAM YOUNG LVuniversityI1RSIT Y INZT 13 PARTIAL fulfillment ortheOFTHEOF THE requirementsrequimrequam1 L mentsWENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF FASTERMASTER orOF ARTS by ralph L mcbride 1957 00oo i acknowledgements sincere appreciation is extended to many for their help in the preparation of this thesis special gratitude is extended to dr leroy hafen for whom I1 hold great esteem my committee chairman for his valuable assistance and helpful attitude dr briant jacobs committee member is given acknowledgement for his inspiration and guidance the cooperation and assistance of the library staffs of the erigBrigbrighamhenahevahavayoung -

Vibrating Mail on the Overland Route

Defaults, Delays and Vibrations on the Overland Mail Route July 1, 1861 to May 10, 1869 by Richard Frajola The Precursor Transcontinental Mail Routes In the period before July 1, 1861 when the daily mail route commenced, there were several postal routes utilized to handle mail between points east of the Mississippi River, and the vast areas of the West. The clamor for ever- faster postal communication increased dramatically with the mineral discoveries in California in 1848 that precipitated a massive migration. The first government contract mail service between New York to San Francisco was inaugurated in 1848. This service utilized the route from New York City by steamer to Chagres (Aspinwall), by land across the Isthmus of Panama to Panama City, and thence by steamer to San Francisco. This route remained the gold-standard service against which all overland routes were judged. The schedule for this service varied over the next twenty years but for much of the time it was a tri-monthly mail from New York and a bi-monthly mail from San Francisco. An additional twice monthly postal route, via Tehuantepec Peninsula, connecting New Orleans with San Francisco operated briefly between October 1858 and October 1859. Although multiple routes for mail carriage became available in the period after 1850, the “Via Panama” service remained the default until December 15, 1859, when the Southern, or “Butterfield,” overland route became the default for letter mail from San Francisco to New York. Prior to that date a sender was required to endorse the cover to be sent overland for it to be sent on the overland route. -

New Mexico Information Packet

! ! ! Table of Contents ! Contact Information……………………………………………………...2 ! Mission, Vision, Goals………………………………………………….…3 ! Mission Site Information…………………………………………….…4 ! Frequently Asked Questions………………………………………….5 ! Cost……………………………………………………………………………….7 ! Housing, Food, Transportation……………………………………...9 ! Dress Code…………………………………………………………………..10 ! Packing List………………………………………………………………….11 ! Schedule………………………………………………………………………12 ! Airlines………………………………………………………………………..13 ! Rental Cars…………………………………………………………………..15 !1 ! ! New Mexico ! Thank you for your interest in taking a trip with One Way Ministries! We are excited that God will use you in powerful ways as you minister in the name of Jesus Christ. ! Please read over this packet of information and contact us with any questions. We are here to help you in any way possible. Here’s how you can get in touch with us: ! Phone: Office: (205) 620-9190 Cell: (205) 706-7669 (JT) (205) 706-8173 (Sheryl) Fax: 1-800-861-3132 ! Email: Office: [email protected] JT: [email protected] Joseph: [email protected] Karen: [email protected] Meghan: [email protected] Sheryl: [email protected] Accounting: [email protected] ! (For all staff members, simply use the person’s first name followed by @1wayministries.org.) ! !2 Mission The mission of 1 Way Ministries is to boldly share the whole truth of God’s Word through evangelism and outreach to impoverished, forgotten and desperate people groups by motivating and mobilizing believers in Jesus Christ to take the first steps in reaching the world with the message of eternal hope. Vision • to share the message of the Gospel through effective evangelism training with believers and church leaders. • to encourage leaders in disciple-making and the kingdom work of evangelism. • to preach boldly, without compromise, the whole truth of God’s Word in every opportunity God provides. -

February 9, 2015)

Contact: Megan van Frank, 801.359.9670 ext. 110 [email protected] Photos Available Upon Request For Immediate Release (February 9, 2015) Beehive Archive Welcome to the Beehive Archive—your weekly bite-sized look at some of the most pivotal—and peculiar—events in Utah history. With all of the history and none of the dust, the Beehive Archive is a fun way to catch up on Utah’s past. Beehive Archive is a production of the Utah Humanities Council, provided to local papers as a weekly feature article focusing on Utah history topics drawn from our award-winning radio series, which can be heard each week on KCPW and Utah Public Radio. To Utah By Stagecoach The stagecoach is a legendary symbol of the American West, part of a transportation network that spanned the continent. How did Utah fit into this network? Traveling to Utah was difficult – to say the least – in the mid-19th Century. Major land routes between the east and west coasts skirted Utah to the north and south. The need for easier communication between Salt Lake City and the outside world drove the development of new transportation routes for both mail and passengers. The first such stagecoach service was started in 1858 by George Chorpenning using the Central Overland Route, a new trail that ran through central Utah and Nevada to California. The route was originally scouted in 1855 by Howard Egan, who used it to drive cattle, and was improved by US Army Captain James Simpson, who used it to supply Camp Floyd during the Utah War.