Cocconeis Rouxii Héribaud & Brun a Forgotten, but Common Benthic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogeography of a Tertiary Relict Plant, Meconopsis Cambrica (Papaveraceae), Implies the Existence of Northern Refugia for a Temperate Herb

Article (refereed) - postprint Valtueña, Francisco J.; Preston, Chris D.; Kadereit, Joachim W. 2012 Phylogeography of a Tertiary relict plant, Meconopsis cambrica (Papaveraceae), implies the existence of northern refugia for a temperate herb. Molecular Ecology, 21 (6). 1423-1437. 10.1111/j.1365- 294X.2012.05473.x Copyright © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd. This version available http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/17105/ NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This document is the author’s final manuscript version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this and the publisher’s version remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from this article. The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trademarks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. 1 Phylogeography of a Tertiary relict plant, Meconopsis cambrica 2 (Papaveraceae), implies the existence of northern refugia for a 3 temperate herb 4 Francisco J. Valtueña*†, Chris D. Preston‡ and Joachim W. Kadereit† 5 *Área de Botánica, Facultad deCiencias, Universidad de Extremadura, Avda. de Elvas, s.n. -

Bulletin Municipal Juillet 2016

Bulletin municipal Juillet 2016 L’Edito du Maire DES ADIEUX CHARGES UNE BONNE NOUVELLE D’EMOTION Pour ce cinquième bulletin, Mr le A l’initiative Maire, nous fait part …………….. de la municipalité et avec la collaboration de Guylaine et Didier COCHAUT ……….. ……… Suite Page 3 …….. Suite Page 3 UN LIEU INCONTOURNABLE La maison du site du Claux est la dernière du réseau des Maisons de Site du Grand Site …………………… ……… suite page 2 ……….. Suite Page 4 UN COMITE DES FETES TOUJOURS PRET À UN CLUB DES AINES QUI N’A PAS ANIMER SA COMMUNE DIT SON DERNIER MOT ! Soirée carnaval, Fête de la Randonnée ………. Après une année de transition……… …………Suite Page 5 …………..Suite Page 6 UNE ASSOCIATION QUI ŒUVRE POUR LA SOUVENIRS …………. SOUVENIRS MEMOIRE DU PATRIMOINE DES ANNEES 50 Livrets disponibles à la Maison de la montagne ……….Suite Page 8 …………….Suite Page 7 UN MOT D’HISTOIRE POUR NE PAS OUBLIER… …. Suite Page 9 et 10 Sommaire L’édito du maire Pour notre bulletin de l’année 2016, LE CLAUX a alterné avec le chaud et le froid. Des bonnes et mauvaises nouvelles : ▪ La mauvaise nouvelle est la fermeture de l’école ; Nous avions avec Cheylade et Saint-Hippolyte un regroupement pédagogique qui fonctionnait à la satisfaction de tous. A la rentrée toutes les classes seront groupées à Cheylade. Une fois encore, on tombe dans un travers bien français qui consiste à casser quelque chose qui fonctionnait bien et on se trouve dans l’incapacité de réformer ce qui ne va pas. ▪ Les bonnes nouvelles sont : ➢ l’ouverture de l’épicerie : après maintes péripéties, avec la disponibilité d’un local et son réaménagement par les employés communaux, nous avons obtenu que Mr et Mme COCHAUT exploitent une succursale saisonnière de leur épicerie. -

World Geomorphological Landscapes

World Geomorphological Landscapes Series Editor: Piotr Migoń For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10852 Monique Fort • Marie-Françoise André Editors Landscapes and Landforms o f F r a n c e Editors Monique Fort Marie-Françoise André Geography Department, UFR GHSS Laboratory of Physical CNRS UMR 8586 PRODIG and Environmental Geography (GEOLAB) University Paris Diderot-Sorbonne-Paris-Cité CNRS – Blaise Pascal University Paris , France Clermont-Ferrand , France Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the fi gures and tables which have been reproduced from other sources. Anyone who has not been properly credited is requested to contact the publishers, so that due acknowledgment may be made in subsequent editions. ISSN 2213-2090 ISSN 2213-2104 (electronic) ISBN 978-94-007-7021-8 ISBN 978-94-007-7022-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-7022-5 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013944814 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

Geotour France 1: Cantal and the Chaîne Des Puys (Auvergne); Volcanoes “A La Carte”

www.aulados.net Geotours France 1 2021 Geotour France 1: Cantal and the Chaîne des Puys (Auvergne); volcanoes “a la carte” The Miocene to Holocene “green” volcanoes of France. If someone wants to learn volcanology or simply enjoy an unforgettable natural environment, "this" is the perfect place in Europe. R. Oyarzun1 & P. Cubas2 Retired Associate Professors of Geology1 and Botany2, UCM-Madrid (Spain) Fall and flow pyroclastic deposits in the Puy de Lemptégy, an “open-cast” volcano. Dates of the visits to the places here presented: August 7-11, 2008 August 9-13, 2009 August 8-11, 2014 Geotours travelers: P. Cubas & R. Oyarzun Aula2puntonet - 2021 1 www.aulados.net Geotours France 1 2021 Introduction Our little tribute to Professor Robert Brousse (1929-2010), Auvergnat and geologist, with a superb in- depth knowledge of his region. For an amazing “volcanic trip” to the heart of France, one must visit and tour the magnificent departments of Cantal and Puy de Dôme. These departments host what it was the largest volcano in Europe and the famous Chaîne des Puys, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The word “puy” (UK : 'pwi) comes from the Latin podium, and means “height” or “hill” (Godard, 2013). Both the Cantal volcano and the Chaîne des Puys are located in the French Central Massif. Chaîne des Puys France French Central Massif Cantal Clermont Ferrand The French Central Massif and location of the Chaîne des Puys and Cantal. Images1,2. Without even mentioning the geology (in general), or the volcanoes (in particular), the Auvergne region is internationally recognized for many reasons, its landscapes with impressive peaks, valleys, ravines, forests, lakes, dormant volcanoes (although as in the Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: you never know ...) and so on, its remarkable religious (Romanesque and Gothic) and military architectural heritage (countless castles and fortresses), and also, why not, for its gastronomy (after all is France, isnt’it?). -

The Massif Central

© Lonely Planet 224 The Massif Central HIGHLIGHTS The last turn before the summit of Puy Mary (p233) Puffing through the pedal motions of the Tour de France route up the Puy-de-Dôme (p232) Sleeping in a mountain buron (shepherds hut; p234) TErraIN Rolling hills dotted with volcanic puys in the north and divided by older, jagged mountain ranges in the south. Telephone Code – 04 www.auvergne-tourisme.info Between the knife-edge Alps and the green fields of the Limousin sprawls the Massif Central, one of the wildest, emptiest and least-known corners of France. Cloaked with a mantle of grassy cones, snow-flecked peaks and high plateaus left behind by long-extinct volcanoes, the Massif Central is a place where you can feel nature’s heavy machinery at work. Deep underground, hot volcanic springs bubble into the spa baths and mineral-water factories of Vichy and Volvic, while high in the mountains, trickling streams join forces to form three of France’s greatest rivers: the Dordogne, the Allier and the Loire. The Massif Central covers roughly the area of the Auvergne region, comprising the départements of Allier, Puy-de-Dôme, Cantal and Haute-Loire. Deeply traditional and still dominated by the old industries of agriculture and cattle farming, the Massif Central is home to the largest area of protected landscape in France, formed by two huge regional parks: the Parc Naturel Régional des Volcans d’Auvergne and its neighbour, the Parc Naturel Régional du Livradois-Forez. With so much natural splendour on offer, the Massif Central is, unsurprisingly, a paradise for those who like their landscapes rude and raw. -

Traces of Ancient Range Shifts in a Mountain Plant Group (Androsace Halleri Complex, Primulaceae)

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 3890–3901 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03342.x TracesBlackwell Publishing Ltd of ancient range shifts in a mountain plant group (Androsace halleri complex, Primulaceae) CHRISTOPHER J. DIXON, PETER SCHÖNSWETTER and GERALD M. SCHNEEWEISS Department of Biogeography and Botanical Garden, University of Vienna, Rennweg 14, A-1030 Vienna, Austria Abstract Phylogeographical studies frequently detect range shifts, both expansions (including long-distance dispersal) and contractions (including vicariance), in the studied taxa. These processes are usually inferred from the patterns and distribution of genetic variation, with the potential pitfall that different historical processes may result in similar genetic patterns. Using a combination of DNA sequence data from the plastid genome, AFLP fingerprinting, and rigorous phylogenetic and coalescence-based hypothesis testing, we show that Androsace halleri (currently distributed disjunctly in the northwestern Iberian Cordillera Cantábrica, the eastern Pyrenees, and the French Massif Central and Vosges), or its ancestor, was once more widely distributed in the Pyrenees. While there, it hybridized with Androsace laggeri and Androsace pyrenaica, both of which are currently allopatric with A. halleri. The common ancestor of A. halleri and the north Iberian local endemic Androsace rioxana probably existed in the north Iberian mountain ranges with subsequent range expansion (to the French mountain ranges of the Massif Central and the Vosges) and allopatric speciation (A. rioxana, -

Pdf Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Tourisme English Press Pack 2020

AUVERGNE-RHÔNE-ALPES TOURISME PRESS PACK Reveal andFEEL REBORN HERE FOR RESPONSIBLE TOURISM “While our ambition -’ to make the top 5 destinations in Europe within 5 years ’- remains unchanged, we do want to build a vision for considerate tourism that addresses not just our economic but also the wider new societal and environmental challenges”. Visitor expectations are changing. Visitors today are looking for more environmentally- Chairman, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Tourisme conscious tourism, for rewarding encounters with people rather than visits to overcrowded sites, for fair trade on local markets, and for active mobility. Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Tourism is aware of these emerging societal expectations and has “We need to chart a new heading, to enable balanced resilient forged a long-term vision to promote France’s second most visited region by engaging a development for our territories and local communities and to meet the core aspirations of our visitors”. path towards consciously considerate and responsible tourism that addresses its economic, Lionel Flasseur environmental and social impacts. Managing Director, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Tourisme You can find the manifesto online at www.tourismebienveillant.org THE TOURISM & HANDICAP BRAND FOR INCLUSIVE TOURISM Over 450 of the region’s tourist-sector professionals (including hotel managers, integrated resorts, tourist attractions, restauranteurs, B&B owners, tourist information offices, and more) have engaged in this inclusive tourism initiative by delivering adaptive solutions to the full spectrum of disability in all its forms—physical, visual, auditory, and mental. You can find all these offers online at auvergnerhonealpes-tourisme.com FEEL REBORN HERE—IN PICTURES Three films have been put together to illustrate the “feel reborn here” brand promise and our vision of considerate tourism. -

Compositae, Senecioneae)

ESCUELA TÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE INGENIEROS DE MONTES UNIVERSIDAD POLITÉCNICA DE MADRID Systematics of Senecio sect. Crociseris (Compositae, Senecioneae) JOEL CALVO CASAS Ingeniero de Montes DIRECTORES CARLOS AEDO PÉREZ INÉS ÁLVAREZ FERNÁNDEZ Doctor en Biología Doctora en Biología Madrid, 2013 Tribunal nombrado por el Mgfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día ....... de .............................. de 2013. Presidente D. .................................................................................................. Vocal D. ......................................................................................................... Vocal D. ......................................................................................................... Vocal D. ......................................................................................................... Secretario D. .................................................................................................. Realizado del acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día ....... de .............................. de 2013 en Madrid. Calificación ………………………………………………… EL PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO “Mutisiam dicam. Numquam vidi magis singularem plantam. Herba clematidis, flos syngenesiae. Quis umquam audivit florem compositum caule scandente, cirrhoso, pinnato in hoc ordine naturali.” “La llamaré Mutisia. En ninguna parte vi planta que le exceda en lo singular: su yerba es de clemátide y su flor de singenesia. ¡Quién tuvo jamás noticia de una flor -

Chromosome Numbers in the Series Rupestria Berger of the Genus

Acta Bot. Neerl. 21(4), August 1972,p. 428-435 Chromosome numbers in the series Rupestria Berger of the genus Sedum L. H. ’t Hart Instituut voor Systematische Plantkunde,Utrecht SUMMARY In the series Rupestria Berger the following chromosome numbers were found: Sedum for- sterianum Sm., 2n = 48 and 96; Sedum montanum Song. & Perr., 2n = 34 and 51; Sedum = Sedum ochroleucum Chaix in Vill., 2n 34 and 68; reflexum L., 2n = 85, 102, and 153; Sedum sediforme (Jacq.) Pau, 2n = 32, 64, and 96; Sedum tenuifolium(Sibth. & Sm.) Strobl, = is of the that for the all 2n 24 and 72. The author opinion present these taxa should be treat- ed as separate species. 1. INTRODUCTION The series within the Sedum L. described in Rupestria genus was by Berger 1930. The species of this groupare very similarin habit. All have approximately terete, linear and acuminate leaves which are rather closely imbricate on the non-flowering shoots. The flowering shoots are 10-60 cm long, with a more or less terminal The flowers with compact, cyme. are 5-7(-8)-merous, erect carpels. Praeger (1921) already used for these species the name Tupestre group’, but did not give a formal description. Webb in Flora Europaea (1964) also placed the species of this group together, although without using the name Rupestria Berger. According to Webb (1964) the European species of this group are the the used and Sedum following (only synonyms by Praeger Berger are added): forsterianum Sm. (= S. rupestre L.); Sedum ochroleucum Chaix in Vill. (= S. anopetalum DC.); Sedum reflexum L.; Sedum sediforme (Jacq.) Pau (= S. -

Past, Current and Potential Future Distributions of Unique Genetic Diversity in a Cold‐Adapted Mountain Butterfly

This is a repository copy of Past, current and potential future distributions of unique genetic diversity in a cold‐adapted mountain butterfly. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/163901/ Article: Minter, Melissa, Dasmahapatra, Kanchon Kumar orcid.org/0000-0002-2840-7019, Thomas, Chris D orcid.org/0000-0003-2822-1334 et al. (5 more authors) (Accepted: 2020) Past, current and potential future distributions of unique genetic diversity in a cold‐adapted mountain butterfly. Ecology and Evolution. ISSN 2045-7758 (In Press) Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Past, current and potential future distributions of unique genetic diversity in a cold‐adapted 2 mountain butterfly 3 Short running title less than 40 characters: Climate change and insect genetic diversity 4 Melissa Minter1*, Kanchon K Dasmahapatra1, Chris D Thomas1, -

Money Hotspots on a Budget and Keen to Invest Wisely? Karen Tait Discovers the Five Safest Places in France to Put Your Property Pounds at the Moment

LOCATION Choosing an area Money hotspots ON A BUDGET AND KEEN TO INVEST WISELY? KAREN tait DISCOVERS THE FIVE SAFEST PLACES IN FRANCE TO PUT YOUR PROPERTY POUNDS AT THE MOMENT hen you buy a The Cantal landscape is all mountain peaks, rivers and lakes, property in great for outdoor pursuits – WFrance, whether shown here are the Truyère gorges for holidays or a full-time move, you’re investing in a way of life, in your personal happiness. It’s not all about money. But having said that, it is good to know you’re making a sound financial investment too. Unlike the UK, where the property market is stuck in the doldrums, France is performing well. In the last year, falling prices have been reversed, and the Notaires de France, who record house prices across FRANCE/R-Cast © ATOUT the country, report a national increase in CANTAL Super Lioran take over. of the new inhabitants to the average house prices of The department with the Panoramic views can be Cantal are predicted to be 7.9% in 2010-11. 1highest price rise is enjoyed from Puy Mary and the Parisians and also from Outside of the capital, Cantal (department number 15) Plomb du Cantal, and the Provence, the Alps and 11 regions saw a higher- in the Auvergne region, with an Truyère gorges are also Côte d’Azur. than-average increase: astounding 18% increase over popular. Manmade attractions “Another factor to be Languedoc-Roussillon the past year. The average include the Garabit viaduct investigated is the change in (12.6%), Nord-Pas de house price in this mountainous (created by someone you may climate – could it be that global Calais (10.1%), Rhône- and peaceful location is have heard of: Gustav Eiffel) warming is contributing Alpes (9.7%), Aquitaine €121,000, considerably under and Plus Beaux Villages Salers towards an even warmer and (9.2%), Provence-Alpes- the national average of and Tournemire. -

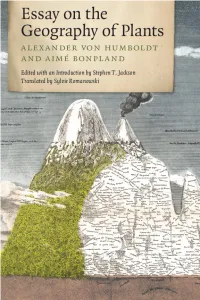

Essay on the Geography of Plants

Essay on the Geography of Plants Essay on the Geography of Plants alexander von humboldt and aime´ bonpland Edited with an Introduction by Stephen T. Jackson Translated by Sylvie Romanowski the university of chicago press :: chicago and london Stephen T. Jackson is professor of botany and ecology at the University of Wyoming. Sylvie Romanowski is professor of French at Northwestern University and author of Through Strangers’ Eyes: Fictional Foreigners in Old Regime France. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-36066-9 (cloth) isbn-10: 0-226-36066-0 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Humboldt, Alexander von, 1769–1859. [Essai sur la géographie des plantes. English] Essay on the geography of plants / Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland ; edited with an introduction by Stephen T. Jackson ; translated by Sylvie Romanowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. isbn-13: 978-0-226-36066-9 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-36066-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Phytogeography. 2. Plant ecology. 3. Physical geography. I. Bonpland, Aimé, 1773–1858. II. Jackson, Stephen T., 1955– III. Romanowski, Sylvie. IV. Title. qk101 .h9313 2009 581.9—dc22 2008038315 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1992.