18 Lund.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The LDS Church and Public Engagement

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Asbury Theological Seminary The LDS Church and Public Engagement: Polemics, Marginalization, Accomodation, and Transformation Dr. Roland E. Bartholomew DOI: 10.7252/Paper. 0000 44 | The LDS Church and Public Engagement: Te history of the public engagement of Te Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as the “Mormons”) is a study of their political, social, and theological shift from polemics, with the associated religious persecution and marginalization, to adjustments and accommodations that have rendered periods of dramatically favorable results. In two generations Mormonism went from being the “ultimate outcast”—its members being literally driven from the borders of the U.S. and persecuted abroad—to becoming the “embodiment of the mainstream” with members fguring prominently in government and business circles nationally and internationally; what one noted journalist has deemed “a breathtaking transformation.”1 I will argue that necessary accommodations made in Church orthodoxy and orthopraxy were not only behind the political, social, and theological “mainstream,” but also consistently outlasted their “acceptability,” as the rapidly changing world’s values outpaced these changes in Mormonism. 1830-1889: MARGINALIZATION Te frst known public engagement regarding Mormonism was when the young Joseph Smith related details regarding what has become known as his 1820 “First Vision” of the Father and the Son. He would later report that “my telling the story had excited a great deal of prejudice against me among professors of religion, and was the cause of great persecution.”2 It may seem strange that Joseph Smith should be so criticized when, in the intense revivalistic atmosphere of the time, many people claimed to have received personal spiritual manifestations, including visions. -

The Mormons Are Coming- the LDS Church's

102 Mormon Historical Studies Nauvoo, Johann Schroder, oil on tin, 1859. Esplin: The Mormons are Coming 103 The Mormons Are Coming: The LDS Church’s Twentieth Century Return to Nauvoo Scott C. Esplin Traveling along Illinois’ scenic Highway 96, the modern visitor to Nauvoo steps back in time. Horse-drawn carriages pass a bustling blacksmith shop and brick furnace. Tourists stroll through manicured gardens, venturing into open doorways where missionary guides recreate life in a religious city on a bend in the Mississippi River during the mid-1840s. The picture is one of prosper- ity, presided over by a stately temple monument on a bluff overlooking the community. Within minutes, if they didn’t know it already, visitors to the area quickly learn about the Latter-day Saint founding of the City of Joseph. While portraying an image of peace, students of the history of Nauvoo know a different tale, however. Unlike other historically recreated villages across the country, this one has a dark past. For the most part, the homes, and most important the temple itself, did not peacefully pass from builder to pres- ent occupant, patiently awaiting renovation and restoration. Rather, they lay abandoned, persisting only in the memory of a people who left them in search of safety in a high mountain desert more than thirteen hundred miles away. Firmly established in the tops of the mountains, their posterity returned more than a century later to create a monument to their ancestral roots. Much of the present-day religious, political, economic, and social power of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traces its roots to Nauvoo, Illinois. -

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Editor's Introduction: in the Land of the Lotus-Eaters

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 10 Number 1 Article 2 1998 Editor's Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters Daniel C. Peterson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Peterson, Daniel C. (1998) "Editor's Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 10 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol10/iss1/2 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Editor’s Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters Author(s) Daniel C. Peterson Reference FARMS Review of Books 10/1 (1998): v–xxvi. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Introduction to the current issue, including editor’s picks. Peterson explores the world of anti-Mormon writing and fiction. Editor's Introduction: In the Land of the Lotus-Eaters Daniel C. Peterson We are the persecuted children of God-the chosen of the Angel Merona .... We are of those who believe in those sacred writings, drawn in Egyptian letters on plates of beaten gold, which were handed unto the holy Joseph Smith at Palmyra. - Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarletl For years, I have marveled at the luxuriant, even rank, growth that is anti-Mormonism. -

Printable Bike

c ycle The ciTy c ycle The ciTy DeStInAtIonS DeStInAtIonS CYCLE THE About the Route: Cycle the City is suit- SLC Main Library: An able for bicyclists who are generally comfortable riding 7 architectural gem designed by on urban streets with bike lanes. the route mostly uses world-renowned architecture firm bike lanes and paths, on fairly flat terrain, with one long, Moshe Safdie and Associates, the CITY gradual hill up lower City Creek Canyon. Library has five floors and over a half-million books. Shops on the Pioneer Park: t he starting point to our route, main floor offer a variety of services, 1 Pioneer Park is the former site of the old Pioneer Fort, such as food, coffee, artwork and a florist. erected the week the first Mormon pioneers arrived in Salt Lake in 1847. today it is home to the twilight t he Leonardo: t his contem- Concert Series, Saturday Farmers’ Market, and many 8 porary museum of art, science and more community activities. technology is named after Leonardo DaVinci. the Leonardo features Temple Square: Situated in one-of-a-kind interactive exhibits, 2 the heart of downtown, temple Square programs, workshops and classes. features the temple, exquisite gardens, tabernacle, and the world headquar- Liberty Park: A classic urban ters of the Church of Jesus Christ of 9 park with a central tree-lined prome- Latter-day Saints. Please dismount and nade, Liberty Park features a walk- walk your bicycle through the Square. ing/biking loop path that you will sample on this ride. Memory Grove: this beauti- t racy Aviary: Located in a tranquil, wooded 3 ful park features several memorials to utah’s veterans, a replica of the 10 setting within Liberty Park, the Aviary is one of the Liberty bell, and hiking trails through a largest in the country: home to over 100 species of botanical garden. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996

Journal of Mormon History Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 1 1996 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1996) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol22/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --The Emergence of Mormon Power since 1945 Mario S. De Pillis, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --The Mormon Nation and the American Empire D. W. Meinig, 33 • --Labor and the Construction of the Logan Temple, 1877-84 Noel A. Carmack, 52 • --From Men to Boys: LDS Aaronic Priesthood Offices, 1829-1996 William G. Hartley, 80 • --Ernest L. Wilkinson and the Office of Church Commissioner of Education Gary James Bergera, 137 • --Fanny Alger Smith Custer: Mormonism's First Plural Wife? Todd Compton, 174 REVIEWS --James B. Allen, Jessie L. Embry, Kahlile B. Mehr. Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894-1994 Raymonds. Wright, 208 --S. Kent Brown, Donald Q. Cannon, Richard H.Jackson, eds. Historical Atlas of Mormonism Lowell C. "Ben"Bennion, 212 --Spencer J. Palmer and Shirley H. -

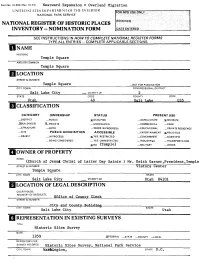

Temple Square AND/OR COMMON Temple Square [LOCATION

Form NO. 10-300 (Rev io-74) Westward Expansion - Overland Migration UNITED STAThS DEPARTMENT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Temple Square AND/OR COMMON Temple Square [LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Temple Square _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Salt Lake City _. VICINITY OF 2 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Utah. 49 Salt Lake 035 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM JSBUILDING(S) X_PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE — ENTERTAINMENT X-REL'GIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X.NO (Temple) —MILITARY _ OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME (.Church, of Jesui Christ of Latter Day Saints ) Mr. Keith Garner,President,Temple STREETS NUMBER Vistors Center Temple Square CITY. TOWN STATE Salt Lake City _ VICINITY OF Utah 84101 HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Office*j- £J of,- County„ Clerk^11 STREET & NUMBER .... City- and County . Building .. .. - - CITY. TOWN Salto 1*. LakeT 7 Cityoj*. STATE Utah REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE 1959 .XFEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Historic Sites _Survey , Park Service CITY. TOWN Washington , STATE D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -XEXCELLENT _DETERIORATED .—UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED AMOVED DATE **•*•*•1912 _FAIR _UNEXPOSED (log cabin) DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Temple Square is a ten acre block in Salt Lake City, the point from which all city streets are numbered. -

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

Temple Square Tours

National Association of Women Judges 2015 Annual Conference Salt Lake City, Utah Salt Lake City Temple Square Tours One step through the gates of Temple Square and you’ll be immersed in 35 acres of enchantment in the heart of Salt Lake City. Whether it’s the rich history, the gorgeous gardens and architecture, or the vivid art and culture that pulls you in, you’ll be sure to have an unforgettable experience. Temple Square was founded by Mormon pioneers in 1847 when they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley. Though it started from humble and laborious beginnings (the temple itself took 40 years to build), it has grown into Utah’s number one tourist attraction with over three million visitors per year. The grounds are open daily from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. and admission is free, giving you the liberty to enjoy all that Temple Square has to offer. These five categories let you delve into your interests and determine what you want out of your visit to Temple Square: Family Adventure Temple Square is full of excitement for the whole family, from interactive exhibits and enthralling films, to the splash pads and shopping at City Creek Center across the street. FamilySearch Center South Visitors’ Center If you’re interested in learning about your family history but not sure where to start, the FamilySearch Center is the perfect place. Located in the lobby level of the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, the FamilySearch Center is designed for those just getting started. There are plenty -1- of volunteers to help you find what you need and walk you through the online programs. -

Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-19-2011 Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R. Ricketts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ricketts, eJ remy R.. "Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jeremy R. Ricketts Candidate American Studies Departmelll This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Commillee: , Chairperson Alex Lubin, PhD &/I ;Se, tJ_ ,1-t C- 02-s,) Lori Beaman, PhD ii IMAGINING THE SAINTS: REPRESENTATIONS OF MORMONISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE BY JEREMY R. RICKETTS B. A., English and History, University of Memphis, 1997 M.A., University of Alabama, 2000 M.Ed., College Student Affairs, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2011 iii ©2011, Jeremy R. Ricketts iv DEDICATION To my family, in the broadest sense of the word v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been many years in the making, and would not have been possible without the assistance of many people. My dissertation committee has provided invaluable guidance during my time at the University of New Mexico (UNM). -

Book Reviews 277

276 Mormon Historical Studies Book Reviews 277 BRANDON S. PLEWE, ed. Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 2012, 272 pp., maps, charts, glossary, bibliography, index, $39.95 hardback.) Reviewed by Benjamin F. Tillman Mapping Mormonism is a remarkable publication that makes a distinguished and lasting contribution to Mormon studies. The atlas contains over five hundred beautifully crafted color maps, timelines, and charts that illustrate Mormonism’s unique history and geography. A treasure-trove of information, the atlas includes over ninety carefully researched and clearly written topical entries by sixty expert scholars. The atlas is organized into four sections based on historical periods and area covered: the Restoration, 1820–1845; the empire of Deseret, 1846–1910; the expanding church, 1910–present; and regional histories. This or- ganization helps the reader navigate through a vast array of information where virtually all of the important church-related topics one can imagine, and more, are mapped and charted. In addition to valuable entries on pioneer historical geographies, the reader will gain added insights from the mapping of a variety of topics including the spiritu- al environment of the Restoration, the Relief Society, agriculture and economic development in Utah, political affiliation, and Book of Mor- mon geographies. Topics with recent histories continuing to the present include church architectural styles, welfare and humanitarian aid, gene- alogy, membership distribution, temples, missionary work, and projected church growth. Likewise, regional histories of the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific detail the church’s beginnings and expansion to the present. -

From Missionary Resort to Memorial Farm: Commemoration and Capitalism at the Birthplace of Joseph Smith, 1905–1925

Keith A. Erekson: Joseph Smith Memorial Farm 1905–1925 69 From Missionary Resort to Memorial Farm: Commemoration and Capitalism at the Birthplace of Joseph Smith, 1905–1925 Keith A. Erekson For The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the twentieth century was a century of commemoration. Opening with statues of Brigham Young and Joseph Smith in Salt Lake City and closing with temples in Palmyra and Nauvoo, these ten decades witnessed a flurry of activity at historic sites, from monuments and celebrations to pageants and re-enactments. During the first half of the century, LDS historic sites developed individually and displayed a wide variety of functions. A suc- cessful exhibit at the 1964 New York World’s Fair prompted Church leaders to integrate proselytizing efforts into the sites, and during the 1960s and 1970s, the tourist-drawing work of the (non-institutional but member-owned) Nauvoo Restoration Inc. demonstrated the practicality and appeal of authentic site reconstruction. The past quarter century has been marked by both proselytizing and authenticity: Church President Spencer W. Kimball addressed a general conference audience via satellite from a newly constructed Peter Whitmer Farm home in 1980, global cel- ebrations commemorated the 1997 sesquicentennial of the pioneer entry in the Salt Lake Valley, and the Church’s internet site presently adver- tises dozens of historic sites.1 The current ubiquity of historic sites belies the fact that the LDS Church has not always maintained them. When the Church purchased the birthplace of Joseph Smith a century ago, it owned only two other historic sites, and when President Joseph F.