FINAL Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Pardos in Vallegrande : an exploration of the role of afromestizos in the foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6m01m9bd Author Weaver Olson, Nathan Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Pardos in Vallegrande: An Exploration of the Role of Afromestizos in the Foundation of Vallegrande, Santa Cruz, Bolivia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Nathan Weaver Olson Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Nancy Postero Professor Eric Van Young 2010 Copyright Nathan Weaver Olson, 2010 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Nathan Weaver Olson is approved and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii DEDICATION For Kimberly, who lived it. iv EPIGRAPH The descent beckons As the ascent beckoned. Memory is a kind of accomplishment, a sort of renewal even an initiation, since the spaces it opens are new places inhabited by hordes heretofore unrealized … William Carlos Williams v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ………………………………………………………………… iii Dedication …………………………………………………………………….. iv Epigraph ………………………………………………………………………. v Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………... vi List of Charts ………………………………………………………………….. viii List of Maps …………………………………………………………………… ix Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………. x Abstract ………………………………………………………………………… xii Introduction: Viedma and Vallegrande…………………………...……………. 1 Chapter 1: Representations of the Past ………………………………………… 10 Viedma‘s Report ………………………………………………………. 10 Vallegrande Responds …………………………………………………. 18 Pardos and Caballeros Pardos …………………………………………. 23 A Hegemonic Narrative ……………………………………………….. 33 Chapter 2: Vallegrande as Region and Frontier ………………………………. -

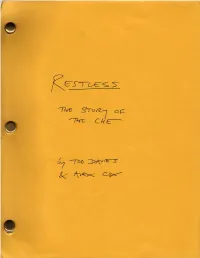

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

Case 15-2247, Document 188-1, 08/01/2019, 2621852, Page1 of 7 15‐2220(L) United States v. Sierra (Carlos Lopez) United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit AUGUST TERM 2018 Nos. 15‐2220(L), 15‐2247(CON), 15‐2257(CON) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. LEONIDES SIERRA, AKA SEALED DEFENDANT 1, AKA JUNITO, AKA JUNIOR, ET AL., Defendants, CARLOS LOPEZ, AKA SEALED DEFENDANT 15, AKA CARLITO, LUIS BELTRAN, AKA SEALED DEFENDANT 26, AKA GUALEY, FELIX LOPEZ‐CABRERA, AKA SEALED DEFENDANT 14, AKA SUZTANCIA, Defendants‐Appellants. ARGUED: MAY 6, 2019 DECIDED: AUGUST 1, 2019 Before: NEWMAN, JACOBS, DRONEY, Circuit Judges. Carlos Lopez, Luis Beltran, and Felix Lopez‐Cabrera appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York sentencing them, inter alia, to mandatory minimum terms of life imprisonment applicable to convictions for murder in aid of racketeering. On appeal, the defendants argue that because they were between 18 and 22 years old 1 Case 15-2247, Document 188-1, 08/01/2019, 2621852, Page2 of 7 when the murders were committed, a mandatory life sentence is cruel and unusual in violation of the Eighth Amendment. Lopez additionally argues that his mandatory life sentence is cruel and unusual because he did not kill, attempt to kill, or intend to kill the victims of his crimes. Affirmed. ____________________ MATTHEW LAROCHE, Assistant United States Attorney (Micah W.J. Smith, Margaret Garnett, Assistant United States Attorneys, on the brief), United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, New York, NY, for Appellee. -

Los Trinitarios (3NI) Was Formed the Late 19891 in New York by Either Julio Marines

Organization Data Sheet: Los Trinitarios Author: Scott Olmstead Review: Phil Williams A. When the organization was formed + brief history Los Trinitarios (3NI) was formed the late 19891 in New York by either Julio Marines (AKA: “Caballo”) or Pedro Nunez (AKA: “El Caballon”)2 in the Rikers Island Correction Facility.3 The majority of sources refer to Julio Marines as the gang’s founder, but the History Channel’s “Machete Slaughter” refers to Pedro Nunez instead. The gang was initially comprised of various Dominican gang members looking for protection while incarcerated. When released, the gang went into organized criminal activity, based in New York’s Washington Heights.4 The name seems to be a reference to a founding party of the Dominican Republic of the same name. Trinitarios also means “Trinity or the Special One.”5 New York Law Enforcement considers 3NI to be one of the fastest growing gangs in the Northeast. Moto: "Dios, Patria y Libertad" (DPL) which means God, Country, and Liberty The gang has spread throughout the Eastern United States and the Dominican Republic. In January 2010, the top two leaders of the gang were killed. The gang is still in operation. The “Primera” of the Rhode Island chapter was arrested in August 2010.6 B. Types of illegal activities engaged in, a. In general Trafficking, distribution, prison protection, kidnapping,7 armed robbery.8 b. Specific detail: types of illicit trafficking activities engaged in “Marijuana, MDA, cocaine and crack cocaine,”9 heroin,10 and ecstasy (MDMA).11 C. Scope and Size a. Estimated size of network and membership There are up to 30,000 members worldwide, with most members active in the US. -

The Mexican General Officer Corps in the US

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Latin American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2011 Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. Javier Ernesto Sanchez Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds Recommended Citation Sanchez, Javier Ernesto. "Valor Wrought Asunder: The exM ican General Officer Corps in the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847.." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ltam_etds/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Javier E. Sánchez Candidate Latin-American Studies Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: L.M. García y Griego, Chairperson Teresa Córdova Barbara Reyes i VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846 -1847 by JAVIER E. SANCHEZ B.B.A., BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO 2009 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2011 ii VALOR WROUGHT ASUNDER: THE MEXICAN GENERAL OFFICER CORPS IN THE U.S.-MEXICAN WAR, 1846-1847 By Javier E. Sánchez B.A., Business Administration, University of New Mexico, 2008 ABSTRACT This thesis presents a reappraisal of the performance of the Mexican general officer corps during the U.S.-Mexican War, 1846-1847. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

Che 1Ère Partie: L'argentin 2E Partie: Guerilla

Fiche pédagogique Che 1ère partie: L'Argentin 2e partie: Guerilla Sortie prévue en salles 7 janvier 2009 (1ère partie) 28 janvier 2009 (2ème partie) Film long métrage de fiction, en deux parties, USA/France/ Espagne, 2008 Résumé l'éducation va de pair avec l'indépendance. Les Américains Réalisation : 1ère partie: L'Argentin envoyés en renfort pour soutenir Steven Soderbergh ("Traffic", l'armée cubaine sont impressionnés "Solaris", "Ocean's eleven"…) Comme le sous-titre l'indique, Le par l'organisation des docteur Ernesto Guevara est né en révolutionnaires : dans leur camp, Interprètes : Argentine en 1928. Bien qu'il se soit une école, une infirmerie, un hôpital, Benicio Del Toro (le Che), très jeune impliqué dans différents et même une centrale électrique. Demiàn Bichir (Fidel Castro), mouvements politiques (au Pérou, Toute cette première partie est Rodrigo Santoro (Raùl Castro), en Colombie, en Bolivie ou au rythmée par des extraits en noir et Julia Ormond (Lisa Howard), Guatemala, qu'il traverse à blanc de la visite du Che à New York Catalina Santino Moreno l'occasion de deux voyages latino- en 1964, de la rue (où il est traité (Aleida March), Joachim de américains de plusieurs mois; ce que d'assassin), à l'ONU, où il condamne Almeida (René Barrientos), développait le film "Carnets de l'oppression des peuples latino- Carlos Bardem (Moisés voyage" (2004) de Walter Salles), le américains ("Les 200 millions de Guevara), Marc-André Grondin film ne remonte pas plus tôt que latino-américains qui crèvent de faim (Régis Debray)... 1955. Cette année-là, à Mexico où il se tuent à la tâche pour produire des s'est exilé, Raùl Castro invite son biens pour l'économie des Etats- Scénario et dialogues : ami Guevara, qu'il avait rencontré au Unis") et où il essaie de retourner les Peter Buchman Guatemala, et lui présente son frère, valeurs admises ("Cuba est libre, les Fidel, exilé lui aussi, suite à Etats-Unis sont une prison") : le Production : Steven l'amnistie des prisonniers cubains de représentant des Etats-Unis n'est Soderbergh, Laura Bickford… 1955. -

Chicana/Os Disarticulating Euromestizaje By

(Dis)Claiming Mestizofilia: Chicana/os Disarticulating Euromestizaje By Agustín Palacios A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Laura E. Pérez, Chair Professor José Rabasa Professor Nelson Maldonado-Torres Universtiy of California, Berkeley Spring 2012 Copyright by Agustín Palacios, 2012 All Rights Reserved. Abstract (Dis)Claiming Mestizofilia: Chicana/os Disarticulating Euromestizaje by Agustín Palacios Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Laura E. Pérez, Chair This dissertation investigates the development and contradictions of the discourse of mestizaje in its key Mexican ideologues and its revision by Mexican American or Chicana/o intellectuals. Great attention is given to tracing Mexico’s dominant conceptions of racial mixing, from Spanish colonization to Mexico’s post-Revolutionary period. Although mestizaje continues to be a constant point of reference in U.S. Latino/a discourse, not enough attention has been given to how this ideology has been complicit with white supremacy and the exclusion of indigenous people. Mestizofilia, the dominant mestizaje ideology formulated by white and mestizo elites after Mexico’s independence, proposed that racial mixing could be used as a way to “whiten” and homogenize the Mexican population, two characteristics deemed necessary for the creation of a strong national identity conducive to national progress. Mexican intellectuals like Vicente Riva Palacio, Andrés Molina Enríquez, José Vasconcelos and Manuel Gamio proposed the remaking of the Mexican population through state sponsored European immigration, racial mixing for indigenous people, and the implementation of public education as a way to assimilate the population into European culture. -

Beyond Empire and Nation (CS6)-2012.Indd 1 11-09-12 16:57 BEYOND EMPIRE and N ATION This Monograph Is a Publication of the Research Programme ‘Indonesia Across Orders

ISBN 978-90-6718-289-8 ISBN 978-90-6718-289-8 9 789067 182898 9 789067 182898 Beyond empire and nation (CS6)-2012.indd 1 11-09-12 16:57 BEYOND EMPIRE AND N ATION This monograph is a publication of the research programme ‘Indonesia across Orders. The reorganization of Indonesian society.’ The programme was realized by the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation (NIOD) and was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Published in this series by Boom, Amsterdam: - Hans Meijer, with the assistance of Margaret Leidelmeijer, Indische rekening; Indië, Nederland en de backpay-kwestie 1945-2005 (2005) - Peter Keppy, Sporen van vernieling; Oorlogsschade, roof en rechtsherstel in Indonesië 1940-1957 (2006) - Els Bogaerts en Remco Raben (eds), Van Indië tot Indonesië (2007) - Marije Plomp, De gentleman bandiet; Verhalen uit het leven en de literatuur, Nederlands-Indië/ Indonesië 1930-1960 (2008) - Remco Raben, De lange dekolonisatie van Indonesië (forthcoming) Published in this series by KITLV Press, Leiden: - J. Thomas Lindblad, Bridges to new business; The economic decolonization of Indonesia (2008) - Freek Colombijn, with the assistance of Martine Barwegen, Under construction; The politics of urban space and housing during the decolonization of Indonesia, 1930-1960 (2010) - Peter Keppy, The politics of redress; war damage compensation and restitution in Indonesia and the Philippines, 1940-1957 (2010) - J. Thomas Lindblad and Peter Post (eds), Indonesian economic decolonization in regional and international perspective (2009) In the same series will be published: - Robert Bridson Cribb, The origins of massacre in modern Indonesia; Legal orders, states of mind and reservoirs of violence, 1900-1965 - Ratna Saptari en Erwiza Erman (ed.), Menggapai keadilan; Politik dan pengalaman buruh dalam proses dekolonisasi, 1930-1965 - Bambang Purwanto et al. -

Fanon's Black Skin, White Masks on Race Consciousness by Carolyn

Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks on Race Consciousness by Carolyn Cusick, Vanderbilt University Readers of Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks often disagree about whether or not Fanon is arguing for or against the perpetuation of racial categories.1 One interpretation suggests that Fanon’s sociogenic analysis demonstrates the inevitability, if not the necessity, of racial categories. These readers, namely Kathryn Gines in “Fanon and Sartre 50 Years Later: To Retain or Reject the Concept of Race”2 focus on Chapter Five, “The Lived Experience of the Black.” Originally published as a response to Sartre’s “Black Orpheus,” Fanon’s essay introduced Léopold Senghor’s anthology of négritude poetry. In “Black Orpheus” Sartre claims that the négritude movement is essential for a new kind of humanism that will free us from racist thinking, free us from a world divided by race: The unity which will come eventually, bringing all oppressed peoples together in the same struggle, must be preceded in the colonies by what I shall call the moment of separation or negativity: this anti-racist racism is the only road that will lead to the abolition of racial differences.3 Fanon’s response is direct: “Jean-Paul Sartre, in this work, has destroyed black zeal. … I needed not to know. This struggle, this new decline had to take on an aspect of completeness.”4 Sartre’s declaring an end to racialism undermines the power of experiencing blackness positively; rendering it as a temporary move on the way to universal humanism makes it almost powerless. To succeed, négritude has to be able to be experienced as absolute. -

Proceedings First Annual Palo Alto Conference

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE An International Conference on the Mexican-American War and its Causes and Consequences with Participants from Mexico and the United States. Brownsville, Texas, May 6-9, 1993 Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site Southwest Region National Park Service I Cover Illustration: "Plan of the Country to the North East of the City of Matamoros, 1846" in Albert I C. Ramsey, trans., The Other Side: Or, Notes for the History of the War Between Mexico and the I United States (New York: John Wiley, 1850). 1i L9 37 PROCEEDINGS OF THE FIRST ANNUAL PALO ALTO CONFERENCE Edited by Aaron P. Mahr Yafiez National Park Service Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site P.O. Box 1832 Brownsville, Texas 78522 United States Department of the Interior 1994 In order to meet the challenges of the future, human understanding, cooperation, and respect must transcend aggression. We cannot learn from the future, we can only learn from the past and the present. I feel the proceedings of this conference illustrate that a step has been taken in the right direction. John E. Cook Regional Director Southwest Region National Park Service TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. A.N. Zavaleta vii General Mariano Arista at the Battle of Palo Alto, Texas, 1846: Military Realist or Failure? Joseph P. Sanchez 1 A Fanatical Patriot With Good Intentions: Reflections on the Activities of Valentin GOmez Farfas During the Mexican-American War. Pedro Santoni 19 El contexto mexicano: angulo desconocido de la guerra. Josefina Zoraida Vazquez 29 Could the Mexican-American War Have Been Avoided? Miguel Soto 35 Confederate Imperial Designs on Northwestern Mexico. -

De Ernesto, El “Che” Guevara: Cuatro Miradas Biográficas Y Una Novela*

Literatura y Lingüística N° 36 ISSN 0716 - 5811 / pp. 121 - 137 La(s) vida(s) de Ernesto, el “Che” Guevara: cuatro miradas biográficas y una novela* Gilda Waldman M.** Resumen La escritura biográfica, como género, alberga en su interior una gran diversidad de métodos, enfoques, miradas y modelos que comparten un rasgo central: se trata de textos interpre- tativos, pues ningún pasado individual se puede reconstruir fielmente. En este sentido, cabe referirse a algunas de las más importantes biografías existentes sobre el Che Guevara, como La vida en rojo, de Jorge G. Castañeda, (Alfaguara 1997); Che Ernesto Guevara. Una leyenda de nuestro siglo, de Pierre Kalfon (Plaza y Janés, 1997); Che Guevara. Una vida revo- lucionaria, de John Lee Anderson (Anagrama, 2006) y Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, de Paco Ignacio Taibo II (Planeta, 1996). Por otro lado, en la vida del Che, hay silencios oscuros que las biografías no cubren, salvo de manera muy superficial. Algunos de estos vacíos son retomados por la literatura, por ejemplo, a través de la novela de Abel Posse, Los Cuadernos de Praga. Palabras clave: Che Guevara, biografías, interpretación, literatura. Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s Lives. Four Biographies and one Novel Abstract The biographical writing, as a genre, shelters inside a wide diversity of methods, approaches, points of view and models that share a central trait: it is an interpretative text, since no individual past can be faithfully reconstructed. In this sense, it is worth referring to some of the most diverse and important biographies written about Che Guervara, (Jorge G. Castañeda: La vida en rojo, Alfaguara 1997; Pierre Kalfon: Che Ernesto Guevara.