Michelangelo's Last Judgment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michelangelo Buonarroti – Ages 10 – Adult | Online Edition

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI – AGES 10 – ADULT | ONLINE EDITION Step 1 - Introducing the Michelangelo Buonarroti Slideshow Guide BEGIN READING HERE MOTIVATION Have you ever had to do a job you really didn’t want to do? Maybe you even got in an argument about it and stormed away angry. Did you end up doing the job anyway, because the person in charge, like a parent or teacher, insisted you do it? That is exactly what happened to our master artist when he was twenty-eight years old. Who would have had that much power over him as an adult? Click Start Lesson To Begin DEVELOPMENT 1. POPE JULIUS II Pope Julius was the powerful ruler of the church in Rome, and he heard about Michelangelo’s amazing talents. The Pope wanted to build beautiful churches and statues in Rome, so people would remember him. He tricked Michelangelo into moving to Rome to work as a sculptor. Sculpting was Michelangelo’s first love as an artist. But soon after Michelangelo began working, the Pope canceled the sculpture and forced him to begin a new project. That’s when the arguments began. Why? Click Next To Change Slide 2. SELF-PORTRAIT Michelangelo considered himself a sculptor. He generally signed his letters and contracts for important works of painting as “Michelangelo the Sculptor.” Time and time again he spoke of his dislike for painting. He claimed it was NOT his profession. Can you guess what Pope Julius asked him to do? (PAINT) Yes, the powerful Julius wanted and insisted that Michelangelo paint, because he was under contract. -

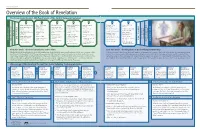

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Contratto Di Quartiere “Borgo Pio”

Venezia, 10-20 novembre 2004 Catalogo della Mostra Comune di Roma Contratto di quartiere “Borgo pio” Il recupero del Passetto e del suo Borgo Il piano-progetto per il recupero urbano dell’intera area di Borgo1 è il risultato di una ricerca sul tema “Analisi di fattibilità del recupero di un monumento: il Passetto di Borgo a Roma” 2. Il programma di riqualificazione generale prodotto dalla ricerca si estende all’intera area del Piano di zona che interessa la civitas Pia e, oltre il Passetto, via della Conciliazione e Borgo Santo Spirito. La proposta generale 1. Ass. Roberto Morassut, direttore Di- partimento VI: dott.sa Virginia Proverbio. ha recepito le esigenze generate dal diffuso degrado del costruito e dalla scarsa vivibilità degli spazi in questa Direttore U.O. n. 6: arch. Gennaro Farina, responsabile del procedimento: arch. “isola” del centro storico ed è avvalorata da un piano di fattibilità sia funzionale che economica. Elide Vagnozzi. Progetto preliminare arch. A. Della Valle, arch D. Fondi, arch. M. Un’area campione, l’isola 19 di Borgo Pio, è stata oggetto di approfondimento con la elaborazione del progetto Alexis, Studio tecnico associato D’Andrea - Manchia, prof. P. Palazzi (cons.). preliminare per un intervento sperimentale di edilizia sovvenzionata inserito nell’ambito del programma di recupero urbano denominato Contratto di quartiere II3. 2. La Ricerca interfacoltà di Ateneo “La Sapienza” è stata svolta negli anni 1994/ Questo progetto, promosso dalle realtà di base operanti nel quartiere, si inserisce in una prima fase di 97. Responsabile della ricerca: prof. P. Palazzi del Dipartimento di Scienze attuazione del Piano di recupero adottato nel 1985 che investe l’area a nord del Passetto. -

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici" on View at the National Gallery of Art March 3 - May 27, 2002

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: February 26, 2002 Passion for Art and Science Merge in "The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici" on View at the National Gallery of Art March 3 - May 27, 2002 Washington, DC -- The Medici family's passion for the arts and fascination with the natural sciences, from the 15th century to the end of the dynasty in the 18th century, is beautifully illustrated in The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici, at the National Gallery of Art's East Building, March 3 through May 27, 2002. Sixty-eight exquisite examples of botanical art, many never before shown in the United States, include paintings, works on vellum and paper, pietre dure (mosaics of semiprecious stones), manuscripts, printed books, and sumptuous textiles. The exhibition focuses on the work of three remarkable artists in Florence who dedicated themselves to depicting nature--Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1626), Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670), and Bartolomeo Bimbi (1648-1729). "The masterly technique of these remarkable artists, combined with freshness and originality of style, has had a lasting influence on the art of naturalistic painting," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "We are indebted to the institutions and collectors, most based in Italy, who generously lent works of art to the exhibition." The Exhibition Early Nature Studies: The exhibition begins with an introductory section on nature studies from the late 1400s and early 1500s. -

Reading 1.2 Caravaggio: the Construction of an Artistic Personality

READING 1.2 CARAVAGGIO: THE CONSTRUCTION OF AN ARTISTIC PERSONALITY David Carrier Source: Carrier, D., 1991. Principles of Art History Writing, University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, pp.49–79. Copyright ª 1991 by The Pennsylvania State University. Reproduced by permission of the publisher. Compare two accounts of Caravaggio’s personality: Giovanni Bellori’s brief 1672 text and Howard Hibbard’s Caravaggio, published in 1983. Bellori says that Caravaggio, like the ancient sculptor Demetrius, cared more for naturalism than for beauty. Choosing models, not from antique sculpture, but from the passing crowds, he aspired ‘only to the glory of colour.’1 Caravaggio abandoned his early Venetian manner in favor of ‘bold shadows and a great deal of black’ because of ‘his turbulent and contentious nature.’ The artist expressed himself in his work: ‘Caravaggio’s way of working corresponded to his physiognomy and appearance. He had a dark complexion and dark eyes, black hair and eyebrows and this, of course, was reflected in his painting ‘The curse of his too naturalistic style was that ‘soon the value of the beautiful was discounted.’ Some of these claims are hard to take at face value. Surely when Caravaggio composed an altarpiece he did not just look until ‘it happened that he came upon someone in the town who pleased him,’ making ‘no effort to exercise his brain further.’ While we might think that swarthy people look brooding more easily than blonds, we are unlikely to link an artist’s complexion to his style. But if portions of Bellori’s text are alien to us, its structure is understandable. -

75. Sistine Chapel Ceiling and Altar Wall Frescoes Vatican City, Italy

75. Sistine Chapel ceiling and altar wall frescoes Vatican City, Italy. Michelangelo. Ceiling frescoes: c. 1508-1510 C.E Altar frescoes: c. 1536-1541 C.E., Fresco (4 images) Video on Khan Academy Cornerstone of High Renaissance art Named for Pope Sixtus IV, commissioned by Pope Julius II Purpose: papal conclaves an many important services The Last Judgment, ceiling: Book of Genesis scenes Other art by Botticelli, others and tapestries by Raphael allowed Michelangelo to fully demonstrate his skill in creating a huge variety of poses for the human figure, and have provided an enormously influential pattern book of models for other artists ever since. Coincided with the rebuilding of St. Peters Basilica – potent symbol of papal power Original ceiling was much like the Arena Chapel – blue with stars The pope insisted that Michelangelo (primarily a sculpture) take on the commission Michelangelo negotiated to ‘do what he liked’ (debateable) 343 figures, 4 years to complete inspired by the reading of scriptures – not established traditions of sacred art designed his own scaffolding myth: painted while lying on his back. Truth: he painted standing up method: fresco . had to be restarted because of a problem with mold o a new formula created by one of his assistants resisted mold and created a new Italian building tradition o new plaster laid down every day – edges called giornate o confident – he drew directly onto the plaster or from a ‘grid’ o he drew on all the “finest workshop methods and best innovations” his assistant/biographer: the ceiling is "unfinished", that its unveiling occurred before it could be reworked with gold leaf and vivid blue lapis lazuli as was customary with frescoes and in order to better link the ceiling with the walls below it which were highlighted with a great deal of gold’ symbolism: Christian ideals, Renaissance humanism, classical literature, and philosophies of Plato, etc. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

Michelangelo's Medici Chapel May Contain Hidden Symbols of Female Anatomy 4 April 2017

Michelangelo's Medici Chapel may contain hidden symbols of female anatomy 4 April 2017 "This study provides a previously unavailable interpretation of one of Michelangelo's major works, and will certainly interest those who are passionate about the history of anatomy," said Dr. Deivis de Campos, lead author of the Clinical Anatomy article. Another recent analysis by Dr. de Campos and his colleagues revealed similar hidden symbols in Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel. More information: Deivis de Campos et al, Pagan symbols associated with the female anatomy in the Medici Chapel by Michelangelo Buonarroti, Clinical Anatomy (2017). DOI: 10.1002/ca.22882 Highlight showing the sides of the tombs containing the bull/ram skulls, spheres/circles linked by cords and the shell (A). Note the similarity of the skull and horns to the Provided by Wiley uterus and fallopian tubes, respectively (B). The shell contained in image A clearly resembles the shell contained in Sandro Botticelli's "The Birth of Venus" (1483), Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy (C). Image B of the uterus and adnexa from Netter's Atlas of Human Anatomy with permission Philadelphia: Elsevier. Credit: Clinical Anatomy Michelangelo often surreptitiously inserted pagan symbols into his works of art, many of them possibly associated with anatomical representations. A new analysis suggests that Michelangelo may have concealed symbols associated with female anatomy within his famous work in the Medici Chapel. For example, the sides of tombs in the chapel depict bull/ram skulls and horns with similarity to the uterus and fallopian tubes, respectively. Numerous studies have offered interpretations of the link between anatomical figures and hidden symbols in works of art not only by Michelangelo but also by other Renaissance artists. -

BOZZETTO STYLE” the Renaissance Sculptor’S Handiwork*

“BOZZETTO STYLE” The Renaissance Sculptor’s Handiwork* Irving Lavin Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton NJ It takes most people much time and effort to become proficient at manipulating the tools of visual creation. But to execute in advance sketches, studies, plans for a work of art is not a necessary and inevitable part of the creative process. There is no evidence for such activity in the often astonishingly expert and sophisticated works of Paleolithic art, where images may be placed beside or on top of one another apparently at random, but certainly not as corrections, cancellations, or “improved” replacements. Although I am not aware of any general study of the subject, I venture to say that periods in which preliminary experimentation and planning were practiced were relatively rare in the history of art. While skillful execution requires prior practice and expertise, the creative act itself, springing from a more or less unselfconscious cultural and professional memory, might be quite autonomous and unpremeditated. A first affirmation of this hypothesis in the modern literature of art history occurred more than a century-and-a-half ago when one of the great French founding fathers of modern art history (especially the discipline of iconography), Adolphe Napoléon Didron, made a discovery that can be described, almost literally, as monumental. In the introduction to his publication — the first Greek-Byzantine treatise on painting, which he dedicated to his friend and enthusiastic fellow- medievalist, Victor Hugo — Didron gave a dramatic account of a moment of intellectual illumination that occurred during a pioneering exploratory visit to Greece in August and September 1839 for the purpose of studying the medieval fresco and mosaic decorations of the Byzantine churches.1 He had, he says, wondered at the uniformity and continuity of the Greek * This contribution is a much revised and expanded version of my original, brief sketch of the history of sculptors’ models, Irving Lavin, “Bozzetti and Modelli. -

The Cathar Crucifix: New Evidence of the Shroud’S Missing History

THE CATHAR CRUCIFIX: NEW EVIDENCE OF THE SHROUD’S MISSING HISTORY By Jack Markwardt Copyright 2000 All Rights Reserved Reprinted by Permission INTRODUCTION Shortly after the dawn of the thirteenth century, a French knight toured the magnificent city that was then Constantinople and, upon entering one of its fabulous churches, observed a clear full-body image of Jesus Christ gracing an outstretched burial cloth.1 Those who advocate that this sydoine was, in fact, the Shroud of Turin, are challenged to credibly account for the relic’s whereabouts both prior to its exhibition in Byzantium and during the period spanning its disappearance in 1204 to its reemergence some one hundred and fifty years later.2 In this paper, the author suggests that medieval crucifixes, orthodox and heretical, evolved from increased awareness of the sindonic image and that these changes mark the historical path of the Shroud as it traveled in anonymity from East to West. THE ORTHODOX CRUCIFIX By the early third century, the cross was the recognized sign of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire and, over the next several centuries, the use of this symbol became so widespread that it is found on most remnants of the era.3 Perhaps repulsed by the ignominious nature of Christ’s death,4 the earliest Christians did not portray his crucifixion. “The custom of displaying the Redeemer on the Cross began with the close of the sixth century”5 and the first datable manuscript image of the Crucifixion is that found in a Syrian Gospel Book written in 586.6 The sudden rise -

Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: Rinascita

Niccolo’ Machiavelli (1469‐1527) • Political career (1498‐1512) • Official in Florentine Republic – Diplomat: observes Cesare Borgia – Organizes Florentine militia and military campaign against Pisa – Deposed when Medici return in 1512 – Suspected of treason he is tortured; retired to his estate Major Works: The Prince (1513): advice to Prince, how to obtain and maintain power Discourses on Livy (1517): Admiration of Roman republic and comparisons with his own time – Ability to channel civil strife into effective government – Admiration of religion of the Romans and its political consequences – Criticism of Papacy in Italy – Revisionism of Augustinian Christian paradigm Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: rinascita • Early Renaissance: 1420‐1500c • ‐‐1420: return of papacy (Martin V) to Rome from Avignon • High Renaissance: 1500‐1520/1527 • ‐‐ 1503: Ascension of Julius II as Pope; arrival of Bramante, Raphael and Michelangelo; 1513: Leo X • ‐‐1520: Death of Raphael; 1527 Sack of Rome • Late Renaissance (Mannerism): 1520/27‐1600 • ‐‐1563: Last session of Council of Trent on sacred images Artistic Renaissance in Rome • Patronage of popes and cardinals of humanists and artists from Florence and central/northern Italy • Focus in painting shifts from a theocentric symbolism to a humanistic realism • The recuperation of classical forms (going “ad fontes”) ‐‐Study of classical architecture and statuary; recovery of texts Vitruvius’ De architectura (1414—Poggio Bracciolini) • The application of mathematics to art/architecture and the elaboration of single point perspective –Filippo Brunellschi 1414 (develops rules of mathematical perspective) –L. B. Alberti‐‐ Della pittura (1432); De re aedificatoria (1452) • Changing status of the artist from an artisan (mechanical arts) to intellectual (liberal arts; math and theory); sense of individual genius –Paragon of the arts: painting vs.