Mediterranean Gull

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magheramorne Landslide, Northern Ireland Mechanics and Remedial Measures

Technical report ■The Magheramorne Landslide, Northern Ireland mechanics and remedial measures Richard J. CHANDLER Department of Civil Engineering, Imperial College of Science Technology and Medicine Key words: landslide case study; partial progressive failure; partial first-time failure ; factors of safety; movement observa- tions. 1. Introduction 2. The Magheramorne Landslide Case studies describing landslide investigations are a The Magheramorne landslide is located a few kilo- valuable resource. They provide information on the metres south of the town of Larne, on a coastal slope type and mechanics of the landslides of their geological running down to Larne Lough, a coastal inlet which area, and hence are a useful guide for studies of simi- opens to the Irish Sea; see Fig. 1. At the foot of the lar landslides in the same area or in similar geological slope are a major road (the "Coast Road") and a rail- conditions. Case studies dealing with remedial works way, both of which run on level ground about three to are also of interest, particularly where the effective- four metres above sea level. Away from Larne Lough, ness of the remedial works is reported. to the west, the slope steepens and rises to about 38 m This paper presents a landslide case study which de- above sea level (a.s.l.; Belfast datum) over a distance scribes the investigations and remedial works for a of 150 m, to the foot of a large man-made tip of rock landslide on the east coast of Northern Ireland, high- waste. This tip has side slopes inclined at about 35•‹, lighting those aspects of the study that are thought to and rises to about 100 m a.s.l. -

Mediterranean Gulls Larus Melanocephalus Wintering Along the Mediterranean Iberian Coast: Numbers and Activity Rhythms in the Species’ Main Winter Quarters

J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-011-0673-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Mediterranean Gulls Larus melanocephalus wintering along the Mediterranean Iberian coast: numbers and activity rhythms in the species’ main winter quarters Albert Cama • Pere Josa • Joan Ferrer-Obiol • Jose´ Manuel Arcos Received: 22 June 2010 / Revised: 23 December 2010 / Accepted: 14 February 2011 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2011 Abstract Knowledge of the winter distribution of the which recent data are lacking. Information for the whole Mediterranean Gull Larus melanocephalus is poor. The study area was obtained from a systematic boat-based limited and geographically patchy data on the species’ survey over the continental shelf in 2003. Then, particular winter distribution is of concern because current estimates attention was paid to St. Jordi Gulf, a known hotspot for of the wintering population do not agree with those for the the species, where we studied the temporal patterns in global breeding population. We assessed the winter dis- abundance throughout the winter months, and daily tribution and abundance patterns of this gull in Mediter- activity rhythms, between 2005–2006 and 2008–2009. To ranean Iberia, a historically important wintering area for set our results in a global context, the available informa- tion of the winter range of the species was collated and synthesised. The results indicate that the Iberian Medi- terranean coast is the main winter quarters of the species. An average population of ca. 41,000 individuals was Communicated by P. H. Becker. present in the area, representing approximately half the Electronic supplementary material The online version of this 86,311 individuals (range 50,747–121,875) recorded article (doi:10.1007/s10336-011-0673-6) contains supplementary across the whole of the species’ winter range. -

Travelling with Translink

Belfast Bus Map - Metro Services Showing High Frequency Corridors within the Metro Network Monkstown Main Corridors within Metro Network 1E Roughfort Milewater 1D Mossley Monkstown (Devenish Drive) Road From every From every Drive 5-10 mins 15-30 mins Carnmoney / Fairview Ballyhenry 2C/D/E 2C/D/E/G Jordanstown 1 Antrim Road Ballyearl Road 1A/C Road 2 Shore Road Drive 1B 14/A/B/C 13/A/B/C 3 Holywood Road Travelling with 13C, 14C 1A/C 2G New Manse 2A/B 1A/C Monkstown Forthill 13/A/B Avenue 4 Upper Newtownards Rd Mossley Way Drive 13B Circular Road 5 Castlereagh Road 2C/D/E 14B 1B/C/D/G Manse 2B Carnmoney Ballyduff 6 Cregagh Road Road Road Station Hydepark Doagh Ormeau Road Road Road 7 14/A/B/C 2H 8 Malone Road 13/A/B/C Cloughfern 2A Rathfern 9 Lisburn Road Translink 13C, 14C 1G 14A Ballyhenry 10 Falls Road Road 1B/C/D Derrycoole East 2D/E/H 14/C Antrim 11 Shankill Road 13/A/B/C Northcott Institute Rathmore 12 Oldpark Road Shopping 2B Carnmoney Drive 13/C 13A 14/A/B/C Centre Road A guide to using passenger transport in Northern Ireland 1B/C Doagh Sandyknowes 1A 16 Other Routes 1D Road 2C Antrim Terminus P Park & Ride 13 City Express 1E Road Glengormley 2E/H 1F 1B/C/F/G 13/A/B y Single direction routes indicated by arrows 13C, 14C M2 Motorway 1E/J 2A/B a w Church Braden r Inbound Outbound Circular Route o Road Park t o Mallusk Bellevue 2D M 1J 14/A/B Industrial M2 Estate Royal Abbey- M5 Mo 1F Mail 1E/J torwcentre 64 Belfast Zoo 2A/B 2B 14/A/C Blackrock Hightown a 2B/D Square y 64 Arthur 13C Belfast Castle Road 12C Whitewell 13/A/B 2B/C/D/E/G/H -

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically Or Biologically Significant Marine Areas

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas Title/Name of the area: Ukrainian bays Abstract (in less than 150 words) Area located in the northern coast of the Black Sea, that encompasses 2 marine Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas mostly designated for the importance for several species of gulls, terns and seaducks. More than 1% of the global/biogeographic population of 10 seabird species occur in the area. The area encompasses also the non-breeding distribution of two Vulnerable seabirds – the Velvet Scoter Melanitta fusca and the Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus. Introduction Area located in the northern coast of the Black Sea (Figure 1), in the shallow waters (< 100 m deep) of the Ukranian bays of Yagorlyts'ka, Tendrivs'ka, Karkinits'ka and Dzharylgats'ka. The area includes 2 marine Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (Figure 1), mostly designated for the importance for several species of gulls, terns and seaducks. More than 1% of the global/biogeographic population of 10 seabird species occur in the area (Greater Scaup Aythya marila, Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus, Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, Caspian Gull Larus cachinnans, Little Gull Hydrocoloeus minutus, Slender-billed Gull Larus genei, Mediterranean Gull Larus melanocephalus, Common Tern Sterna hirundo, Sandwich Tern Thalasseus sandvicensis and Caspian Tern Hydroprogne caspia: BirdLife International 2017a, 2017b). The area encompasses also the non- breeding distribution of two Vulnerable seabirds – the Velvet Scoter Melanitta fusca and the Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus (BirdLife International 2017c; Figure 2). Location The area is located in the North coast of Black Sea (ca. -

Laridaerefspart1 V1.2.Pdf

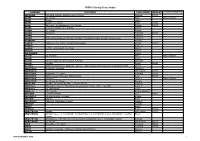

Introduction This is the first of two Gull Reference lists. It includes all those species of Gull that are not included in the genus Larus. I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2014 & 2015 to: [email protected]. Grateful thanks to Wietze Janse (http://picasaweb.google.nl/wietze.janse) and Dick Coombes for the cover images. All images © the photographers. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2014. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 4.2 accessed April 2014]). Cover Main image: Mediterranean Gull. Hellegatsplaten, South Holland, Netherlands. 30th April 2010. Picture by Wietze Janse. Vignette: Ivory Gull. Baltimore Harbour, Co. Cork, Ireland. 4th March 2009. Picture by Richard H. Coombes. Version Version 1.2 (August 2014). Species Page No. Andean Gull [Chroicocephalus serranus] 19 Audouin's Gull [Ichthyaetus audouinii] 37 Black-billed Gull [Chroicocephalus bulleri] 19 Black-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus ridibundus] 21 Black-legged Kittiwake [Rissa tridactyla] 6 Bonaparte's Gull [Chroicocephalus philadelphia] 16 Brown-headed Gull [Chroicocephalus brunnicephalus] 20 Brown-hooded Gull [Chroicocephalus maculipennis] 20 Dolphin Gull [Leucophaeus scoresbii] 31 Franklin's Gull [Leucophaeus pipixcan] 34 Great Black-headed Gull [Ichthyaetus ichthyaetus] 41 Grey Gull [Leucophaeus -

Draft Habitats Regulations Assessment Report of the Draft Plan Strategy September 2019

Local Development Plan 2030 Draft Habitats Regulations Assessment Report of the Draft Plan Strategy September 2019 www.midandeastantrim.gov.uk/planning Have your say Mid and East Antrim Borough Council is consulting on the Mid and East Antrim Local Development Plan – Draft Plan Strategy 2030. Pre-Consultation To allow everyone time to read and digest the draft Plan Strategy we are publishing it in advance of the formal eight week period of public consultation. This period of pre-consultation will run from 17 September 2019 to 15 October 2019. Please note that no representations should be made during this period, as they will not be considered outside of the formal consultation period. During this pre-consultation period, Council’s Local Development Plan team will facilitate a series of public engagement events, exhibitions and drop-in information sessions. Arrangements for these events will be published on our website and in local newspapers in the week commencing 16 September 2019. The aims of these events are to: Promote understanding of the draft Plan Strategy; Explain how it will be tested at Independent Examination; and Provide guidance on the submission of representations to the public consultation. Formal Consultation The draft Plan Strategy will be open for formal public consultation for a period of eight weeks, commencing on 16 October 2019 and closing at 5pm on 11 December 2019. Please note that representations received after the closing date on 11 December will not be considered. The draft Plan Strategy is published along with a range of assessments which are also open for public consultation over this period. -

A6.81 Mediterranean Gull Larus Melanocephalus (Breeding)

A6.81 Mediterranean Gull Larus melanocephalus (breeding) 1. Status in UK Biological status Legal status Conservation status Breeding ✔ Wildlife and General Species of SPEC 4 Countryside Act Protection European Favourable 1981 Conservation conservation status Schedule 1(1) Concern (secure) but concentrated in Europe Migratory ✔ Wildlife (Northern General (UK) Species of Table 4 Ireland) Order 1985 Protection Conservation Importance Wintering ✔ EC Birds Directive Annex I All-Ireland 1979 Vertebrate Red Migratory Data Book 2. Population data Population sizes Selection thresholds Totals in species’ SPA (pairs) suite GB 31 1 23 (74% of GB population) Ireland Biogeographic 184,000 1,840 23 (<0.1% of population biogeographical population) GB population source: Ogilvie et al. 1996 Biogeographic population source: Hagemeijer & Blair 1997 3. Distribution The global distribution of Mediterranean Gull is highly restricted, with breeding limited to just a few localities in Europe, particularly along the northern coast of the Black Sea, from the Danube Delta in the west to the Gulf of Sivash in the east. Breeding occurs very locally elsewhere: some parts of inland Russia, Turkey, the north coast of the Mediterranean including the Aegean and Adriatic Seas, The Netherlands, Britain, and locally in the Baltic. The species is monotypic. In the UK, which is at the north-western limit of the species’ world range, breeding first occurred as recently as 1968 on the south coast of England (Lloyd et al. 1991). It is not known where the birds that breed in England spend the non-breeding season, but it seems likely that they use coastal areas near to the nesting colonies in south-east and south England. -

Pocket Identification Guide of Main Vulnerable Species Incidentally Caught in Turkish Fisheries

POCKET IDENTIFICATION GUIDE OF MAIN VULNERABLE SPECIES INCIDENTALLY CAUGHT IN TURKISH FISHERIES Simplified guide adapted for Turkey (GSAs 22 and 24) from the Identification guide of vulnerable species incidentally caught in Mediterranean fisheries Logos en anglais, avec versions courtes des logos ONU Environnement et PAM La version longue des logos ONU Environnement et PAM doit être utilisée dans les documents ou juridiques. La version courte des logos est destine tous les produits de communication tourns vers le public. IN COLLABORATION WITH FUNDED BY 8 MARINE MAMMALS Stenella Delphinus delphis LC EN coeruleoalba LC VU Common dolphin / Tırtak Striped dolphin / : 2.0-2.6 m / : 2.4 m / Glo Med Çizgili yunus Glo Med NB: 80-90 cm Ad: 1.8-2.6 m NB: 85-95 cm Grampus griseus Risso’s dolphin / Grampus Ad: 3 – 4 m / NB: 1.2 – 1.5 m LC DD Glo Med Monachus monachus Mediterranean monk seal / Akdeniz foku EN CR Tursiops truncatus : 2,51-2,90m / : 2,42m / NB: 100 cm Glo Med Common bottlenose dolphin / Afalina : 2.5 - 3.9 m LC VU : 2.2-3.2 NB: 1-1.2 m Glo Med Physeter macrocephalus VU EN Balaenoptera physalus EN VU Sperm whale / Kaşalot Fin whale / Uzun Balina : 16-18 m / : 11-12 m / NB: 3.3-4.2 m : 18-20 m / : 20-22 m / NB: 6-6.5 m Glo Med Glo Med Ziphius cavirostris Cuvier’s beaked whale / Gagalı balina : up to 7.5 m LC DD : up to 7 m Phocoena Steno NB: 2 -2.7 m Glo Med phocoena bredanensis Harbour porpoise / Balaenoptera acutorostrata Rough-toothed dolphin / LC NE LC Mutur Common minke whale / Kabadişli yunus : 1,8 m LC Mink Balinası Ad: 2.2 – 2.5 -

Paper 1: Population and Growth

MMIIDD && EEAASSTT AANNTTRRIIMM D I S T R I C T D I S T R I C T LLOCAL DDEVELOPMENT PPLAN PPR E P A R A T O R Y SST U D I E S ___________________________________________________ PPAPER 11:: PPOPULATION && GGROWTH JUNE 2014 POPULATION & GROWTH 1 POPULATION & GROWTH CONTENTS Purpose of the Paper....................................................................................................... 6 Aims.................................................................................................................................... 7 Content Overview............................................................................................................ 7 Recommendation............................................................................................................. 7 1.0 Population Profile......................................................................................... 8 . Introduction .................................................................................................... 9 . Section 75 Groups............................................................................................ 10 a. Age Structure............................................................................................. 10 b. Gender & Life Expectancy.......................................................................... 11 c. Marital Status............................................................................................ 12 d. Households with or without dependent children...................................... 13 -

1851 Census for Some Parishes and Townlands in the Barony of Glenarm, Co

1851 Census for some Parishes and Townlands in the Barony of Glenarm, Co. Antrim Ref No. Parish Townland Family Forename Surname Relationship Status Age Occupation Place of Birth Specific Place No. 4590 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 1 HUGH MAGILL HEAD M 45 STONE MASON ANTRIM 4591 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 1 MARGARET MAGILL WIFE M 40 NONE ANTRIM 4592 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 1 MARGARET MAGILL DAUGHTER U 19 SEWING ANTRIM 4593 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 1 JAMES MAGILL SON U 17 SHOEMAKER ANTRIM 4594 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 1 JANE MAGILL DAUGHTER U 12 SEWING ANTRIM 4595 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 1 THOMAS MAGILL SON U 8 NONE ANTRIM 4596 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 2 SARAH MCGILL HEAD U 39 SPINNING FLAX ANTRIM 4597 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 2 MATILDA TWEED DAUGHTER U 15 SEWER ANTRIM 4598 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 2 WILLIAM TWEED SON U 7 AT SCHOOL ANTRIM 4599 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 2 JAMES TWEED SON U 3 NONE ANTRIM 4600 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 3 JAMES REANEY HEAD M 42 LABOURER ANTRIM 4601 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 3 BELLA REANEY WIFE M 40 NONE ANTRIM 4602 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 3 NANCY REANEY DAUGHTER U 15 SEWING ANTRIM 4603 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 3 MARY REANEY DAUGHTER U 12 SEWING ANTRIM 4604 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 3 JAMES REANEY SON U 8 NONE ANTRIM 4605 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 3 HARRIET REANEY DAUGHTER U 5 NONE ANTRIM 4606 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 3 BELLA REANEY DAUGHTER U 1 NONE ANTRIM 4607 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 4 ROBERT RODGERS HEAD M 61 LABOURER ANTRIM 4608 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 4 ANN RODGERS WIFE M 63 NONE ANTRIM 4609 Carncastle BALLYGALLY 4 ROBERT RODGERS SON U 25 LABOURER ANTRIM 4610 Carncastle -

Mediterranean Gull Little Gull

Mediterranean Gull International threshold: 8,400 † Larus melanocephalus GB max: 90 Aug NI max: 3 Jan Three decades ago, Mediterranean Gull was a optional inclusion of this group during WeBS scarce visitor the UK and was just starting to counts should always be taken into account. be noted as a regular, albeit rare, breeding The Solent remains the most important area for species. The increase in the northwest this species with Brading Harbour staying as European population has been evident through the top site. Three birds at Belfast Lough and the expansion of birds throughout Britain from two at Lough Foyle represent the highest the traditional southeast stronghold. During numbers of Mediterranean Gulls ever recorded 2003/04 Mediterranean Gulls were recorded at by WeBS counts in Northern Ireland. 69 sites, compared to just 34 ten years ago. Mediterranean Gulls were reported from a total Surprisingly, the British maximum was of 60 sites during the Winter Gull Roost somewhat lower than in the previous two Survey in winter 2003/04 (BTO data). years. However, as with all gull species the 99/00 00/01 01/02 02/03 03/04 Mon Mean Sites with mean peak counts of 5 or more birds in Great Britain † Brading Harbour 51 35 28 126 57 Aug 59 Newtown Estuary 49 2 65 80 (15) Mar 49 13 13 Chichester Harbour (5) 36 4 (16) (1) Oct 20 Tamar Complex 27 28 14 30 0 20 Ryde Pier to Puckpool Point 15 16 8 45 9 Mar 19 Thames Estuary (7) 13 13 20 27 Sep 18 Swansea Bay 6 11 20 16 19 Jul 14 Camel Estuary 4 (3) (1) 8 25 Oct 12 North Norfolk Coast 10 (4) (6) (13) (1) -

NIFHS Family Trees Index

NIFHS Family Trees Index SURNAME LOCATIONS FILED UNDER MEM. NO OTHER INFORMATION ABRAHAM Derryadd, Lurgan; Aughacommon, Lurgan Simpson A1073 ADAIR Co. Antrim Adair Name Studies ADAIR Belfast Lowry ADAIR Bangor, Co. Down Robb A2304 ADAIR Donegore & Loughanmore, Co. Antrim Rolston B1072 ADAMI Germany, Manchester, Belfast Adami ADAMS Co. Cavan Adams ADAMS Kircubbin Pritchard B0069 ADAMS Staveley ADAMS Maternal Grandparents Woodrow Wilson, President of USA; Ireland; Pennsylvania Wilson 1 ADAMSON Maxwell AGNEW Ballymena, Co. Antrim; Craighead, Glasgow McCall A1168 AGNEW Staveley AGNEW Belfast; Groomsport, Co. Down Morris AICKEN O'Hara ALEXANDER Magee ALLEN Co. Armagh Allen Name Studies ALLEN Corry ALLEN Victoria, Australia; Queensland, Australia Donaghy ALLEN Comber Patton B2047 ALLEN 2 Scotland; Ballyfrench, Inishargie, Dunover, Nuns Quarter, Portaferry all County Down; USA Allen 2 ANDERSON Mealough; Drumalig Davison 2 ANDERSON MacCulloch A1316 ANDERSON Holywood, Co. Down Pritchard B0069 ANDERSON Ballymacreely; Killyleagh; Ballyministra Reid B0124 ANDERSON Carryduff Sloan 2 Name Studies ANDERSON Derryboye, Co Down Savage ANDREWS Comber, Co. Down; Quebec, Canada; Belfast Andrews ANKETELL Shaftesbury, Dorset; Monaghan; Stewartstown; Tyrone; USA; Australia; Anketell ANKETELL Co. Monaghan Corry ANNE??? Cheltenham Rowan-Hamilton APPLEBY Cornwall, Belfast Carr B0413 ARCHBOLD Dumbartonshire, Scotland Bryans ARCHER Keady? Bean ARCHIBALD Libberton, Quothquan, Lanark Haddow ARDAGH Cassidy ARDRY Bigger ARMOUR Reid B0124 ARMSTRONG Omagh MacCulloch A1316 ARMSTRONG Aghadrumsee, Co. Fermanagh; Newtownbutler, Co. Fermanagh; Clones, Monaghan; Coventry; Steen Belfast ARMSTRONG Annaghmore, Cloncarn, Drummusky and Clonshannagh, all Co. Fermanagh; Belfast Bennett ARMSTRONG Co Tyrone; McCaughey A4282 AULD Greyabbey, Co. Down Pritchard B0069 BAIRD Pritchard B0069 BAIRD Strabane; Australia - Melbourne and New South Wales Sproule BALCH O'Hara NIFHS MARCH 2018 1 NIFHS Family Trees Index SURNAME LOCATIONS FILED UNDER MEM.