Equal Protection of the Laws in Public Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliographic Annual in Speech Communication 1973

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 129 CS 500 620 AUTHOR Kennicott, Patrick C., Ed. TITLE Bibliographic Annual in Speech Communication 1573. INSTITUTION Speech Communication Association, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 267p. AVAILABLE FROM Speech. Communication Association, Statler Hiltcn Hotel, New York, N. Y. 10001 ($8.00). EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$12.60 DESCRIPTORS *Behavioral Science Research; *Bibliographies; *Communication Skills; Doctoral Theses; Literature Reviews; Mass Media; Masters Theses; Public Speaking; Research Reviews (Publications); Rhetoric; *Speech Skills; *Theater Arts IDENTIFIERS Mass Communication; Stagecraft ABSTRACT This volume contains five subject bibliographies for 1972, and two lists of these and dissertations. The bibliographies are "Studies in Mass Communication," "Behavioral Studies in Communication," "Rhetoric and Public Address," "Oral Interpretation," and "Theatrical Craftsmanship." Abstracts of many of the doctcral disertations produced in 1972 in speech communication are arranged by subject. ALso included in a listing by university of titles and authors of all reported masters theses and doctoral dissertaticns completed in 1972 in the field. (CH) U S Ol l'AerVE NT OF MEAL.TH r DUCA ICON R ,Stl. I, AWE NILIONAt. INST I IUI EOF E DOCA I ION BIBLIOGRAPHIC ANNUAL CO IN CD SPEECH COMMUNICATION 1973 STUDIES IN MASS COMMUNICATION: A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY, 1972 Rolland C. Johnson BEHAVIORAL STUDIES IN COMMUNICATION, 1972 A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Thomas M. Steinfatt A SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF RHETORIC AND PUBLIC ADDRESS, 1972 Harold Mixon BIBLIOGRAPHY OF STUDIES IN ORAL INTERPRETATION, 1972 James W. Carlsen A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THEATRICAL CRAFTSMANSHIP, 1972. r Christian Moe and Jay E. Raphael ABSTRACTS OF DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS IN THE FIELD OF SPEECH COMMUNICATION, 1972. -

2021 Summer Season

2021 Summer Season How to use this VIRTUAL program book! Here’s how it works: This program book can be viewed on your computer, tablet, or smartphone, and it has all of the information you need about this summer at BVT! It’s also interactive! That means that there are all sorts of things to click on and learn more about! If you see an advertisement or a logo like this one- Go ahead and give it a click! It’ll take you right to that business’s website or social media page. So you can support those who support BVT! And if you see some blue underlined text, like this right here, that’s a click-able link as well! These links can take you to artists’s websites, local businesses, more BVT content, and all kinds of good stuff. And new things will be added all season long as new shows come to the BVT stage! So scroll through and explore… and enjoy the show! Message from the Artistic Director, Karin Bowersock Places, please. At start time of a theatrical performance, the stage manager gives the places call. “Places, please for the top of the show.” It lets actors and run crew know, it's showtime! It's been a bit of a while since we heard the places call at BVT. I don't need to tell you why. And I can't possibly capture in words how it felt to spend a year without you, with only that tentative—and much less satisfying—virtual connection (Ugh, if I never see another zoom room.....). -

Brown V. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society

Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society Manuscript Collection No. 251 Audio/Visual Collection No. 13 Finding aid prepared by Letha E. Johnson This collection consists of three sets of interviews. Hallmark Cards Inc. and the Shawnee County Historical Society funded the first set of interviews. The second set of interviews was funded through grants obtained by the Kansas State Historical Society and the Brown Foundation for Educational Excellence, Equity, and Research. The final set of interviews was funded in part by the National Park Service and the Kansas Humanities Council. KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Topeka, Kansas 2000 Contact Reference staff Information Library & archives division Center for Historical Research KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 6425 SW 6th Av. Topeka, Kansas 66615-1099 (785) 272-8681, ext. 117 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.kshs.org ©2001 Kansas State Historical Society Brown Vs. Topeka Board of Education at the Kansas State Historical Society Last update: 19 January 2017 CONTENTS OF THIS FINDING AID 1 DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION ...................................................................... Page 1 1.1 Repository ................................................................................................. Page 1 1.2 Title ............................................................................................................ Page 1 1.3 Dates ........................................................................................................ -

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data

June 2015 Sunday Morning Talk Show Data June 7, 2015 23 men and 7 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 0 men and 0 women None CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 6 men and 2 women Gov. Chris Christie (M) Mayor Bill de Blasio (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Rep. Michael McCaul (M) Jamelle Bouie (M) Nancy Cordes (F) Ron Fournier (M) Susan Page (F) ABC's This Week with George Stephanopoulos: 6 men and 1 woman Gov. Scott Walker (M) Ret. Gen. Stanley McChrystal (M) Donna Brazile (F) Matthew Dowd (M) Newt Gingrich (M) Robert Reich (M) Michael Leiter (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 5 men and 3 women Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Fmr. Gov. Rick Perry (M) Sen. Joni Ernst (F) Sen. Tom Cotton (M) Fmr. Gov. Lincoln Chafee (M) Jennifer Jacobs (F) Maeve Reston (F) Matt Strawn (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 6 men and 1 woman Fmr. Sen. Rick Santorum (M) Rep. Peter King (M) Rep. Adam Schiff (M) Brit Hume (M) Sheryl Gay Stolberg (F) George Will (M) Juan Williams (M) June 14, 2015 30 men and 15 women NBC's Meet the Press with Chuck Todd: 4 men and 8 women Carly Fiorina (F) Jon Ralston (M) Cathy Engelbert (F) Kishanna Poteat Brown (F) Maria Shriver (F) Norwegian P.M Erna Solberg (F) Mat Bai (M) Ruth Marcus (F) Kathleen Parker (F) Michael Steele (M) Sen. Dianne Feinstein (F) Michael Leiter (M) CBS's Face the Nation with John Dickerson: 7 men and 2 women Fmr. -

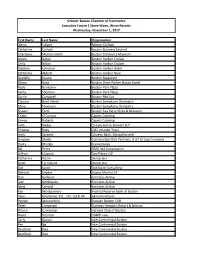

First Name Last Name Organization Alecia Lokpez Babson College

Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce Executive Forum | Steve Wynn, Wynn Resorts Wednesday, November 1, 2017 First Name Last Name Organization Alecia Lokpez Babson College Catherine Carlock Boston Business Journal Charlayne Murrell-Smith Boston Children's Museum Alison Nolan Boston Harbor Cruises Chris Nolan Boston Harbor Cruises Stephen Johnston Boston Harbor Hotel Katherine Abbott Boston Harbor Now Danielle Duane Boston Magazine Alison Rose Boston Omni Parker House Hotel Rudy Hermano Boston Park Plaza Kathy Sheehan Boston Park Plaza Carrie Campbell Boston Red Sox Claudia Bard Veitch Boston Symphony Orchestra Mary Thomson Boston Symphony Orchestra Shawn Ford Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum Kristin O'Connor Capers Catering Emma Roberts Capers Catering John Nadas Choate Hall & Stewart LLP Thomas Riley CIBC Atlantic Trust Jerry Sargent Citizens Bank, Massachusetts Gregory Steele Construction Risk Partners, A JLT Group Company Dusty Rhodes Conventures Bill Perez CRRC MA Corporation Jeffrey Clopeck Day Pitney LLP Katherine Adam Denterlein Scott Farmelant Denterlein Dot Joyce Dot Joyce Consulting Richard Snyder Duane Morris LLP Dan Gallanar Emirates Airline Joel Goldowsky Emirates Airline Matt Schmid Emirates Airline Ken Montgomery Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Ileen Gladstone, P.E., LSP, LEED AP GEI Consultants Patrick Moscaritolo Greater Boston CVB Peter Campisani Gurneys Newport Resort & Marina Steven Cummings Harvard Club of Boston David Heinlein HBMH Law Karly Danais InterContinental Boston Ken Ng InterContinental Boston Bradford Rice InterContinental Boston Bradford Rice InterContinental Boston Al Becker Jack Conway & Company, Inc. Carol C. Bulman Jack Conway & Company, Inc. Maura Hammer John F. Kennedy Library Foundation Steven Rothstein John F. Kennedy Library Foundation Mike Panagako KHJ Kristin Casey KNF&T, Inc. -

President's Report 2016 (PDF Only)

COLLEGE MAGAZINE BEREA COLLEGE MAGAZINE 1 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2016 President’s Report 2016 INVEST in LIVES CONTENTS BEREA COLLEGE MAGAZINE VOLUME 87 Number 2 of GREAT President’s Report 5 President’s Message PROMISE 8 Report on Financial Position Honor Roll of Giving 12 Vice President’s Message 13 John G. Fee Society 13 Founders’ Club Your gift to the Berea Fund helps our 16 President’s Club students graduate with little or no 19 Great Commitments Society debt. For them and their families, it’s a 23 Alumni by Class Year 33 Class Ranking gift that means so much. 35 Student Contributors 40 Honorary Alumni 40 Faculty and Staff Thanks to your gift, David is building a 41 Friends of Berea life after college by serving as an Army 73 Memorial Gifts specialist while pursuing his master’s 76 In Honor of Gifts degree. David is just one of 1600 78 Bequest Gifts examples of how you are changing lives Anna Skaggs ’17 78 Corporate Matching Gifts The fall foliage against a beautiful October sky makes a perfect frame for Phelps 78 Gifts from Foundations, Corporations, Stokes Chapel. every day. and Organizations Departments Make a gift by phone, mail, or visiting 81 Class Notes our website. 83 Passages Front Cover: We think the Quad is beautful in any season, but there really is something special about fall on campus. Photo by Anna Skaggs ’17. 800-457-9846 www.berea.edu/give Berea College CPO 2216 Berea, KY 40404 David Orr ’16, and his son, Emerson BEREA COLLEGE MAGAZINE 3 Lyle D. -

The Affirmative Duty to Integrate in Higher Education

Notes The Affirmative Duty to Integrate in Higher Education I. Introduction In the sixteen years since Brown v. Board of Education,' there has been an evolutionary expansion of the duty to desegregate state ele- mentary and secondary school systems once segregated by law. Southern higher education, however, is today marked by racial separation and by a general inferiority of the historically Negro colleges. This Note will consider whether the Supreme Court's holding in Green v. School Board of New Kent County, Virginia2 has any implications for higher educa- tion. The specific questions to be answered are: (1) since there is still a racially identifiable dual system of public higher educational institu- tions in the South, do the states have a duty to take affirmative steps (beyond establishing racially nondiscriminatory admissions policies) to encourage integration; and (2) if such a duty exists, how do the current circumstances of higher education condition the scope of duty and the remedies which courts may enforce? The need for standards8 to measure a state's compliance with Brown in higher education is particularly acute because the Office of Civil Rights for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare has required several states4 to submit plans 1. 347 U.S. 483 (1954) [hereinafter cited as Brown I]. The second Brown decision, on the question of relief, appears at 349 U.S. 294 (1955) [hereinafter cited as Brown 1I]. 2. 391 U.S. 430 (1968) [hereinafter cited as Green]. 3. The desegregation regulations for elementary and secondary education, 45 C.1,.R. §§ 181.1-181.7 (1968), promulgated by HEWt under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1961, 42 U.S.C. -

Missouri State Association of Negro Teachers OFFICIAL PROGRAM Fifty-Third Annual Convention KANSAS CITY, MO

Missouri State Association of Negro Teachers OFFICIAL PROGRAM Fifty-Third Annual Convention KANSAS CITY, MO. NOV. 16 - 17 - 18 - 19, 1938 LLOYD W. KING Lloyd W. King Democratic Nominee for Re-Election As STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS For the past four years, Missouri Schools have marched forward under Superintendent Lloyd W. King’s leadership. Through the cooperation of the state administration, the legislature, educators, and lay people interested in education, schools have been adequately financed; standards for teachers have been materially raised; the curricula have been revised; many new services have been extended to schools; vocational education has been broadened; a program of vocational rehabilitation for physically-handicapped persons and a program of distributive education have been inaugurated. THE JOURNAL OF EDUCATION LINCOLN HIGH SCHOOL KANSAS CITY General Officers Burt A. Mayberry President Kansas City Miss Emily Russell Second Vice-President St. Louis C. C. Damel First Vice-President St. Joseph Miss Daisy Mae Trice Assistant Secretary Kansas City U. S. Donaldson Secretary St. Louis Miss Dayse F. Baker Treasurer Farmington Miss Bessie Coleman Assistant Secretary St. Louis L. S. Curtis Statistician St. Louis M. R. Martin Auditor Louisiana A. A. Dyer Editor of the Journal St. Louis W. R. Howell Historian Kansas City Joe E. Herriford, Sr. Parlimentarian Kansas City Dayse F. Baker, BURT A. MAYBERRY, DAISY M. TRICE EXECUTIVE BOARD Burt A. Mayberry, Kansas City Chairman U. S. Donaldson, St. Louis Secretary Miss Dayse F. Baker Farmington Mrs. Lillian Booker Liberty Charles H. Brown St. Louis Miss Bessie Coleman St. Louis H. O. Cook Kansas City H. -

State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Florida

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 43 Number 2 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 43, Article 3 Number 2 1964 State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Florida Leedell W. Neyland [email protected] Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Neyland, Leedell W. (1964) "State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 43 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol43/iss2/3 Neyland: State-Supported Higher Education Among Negroes in the State of Fl STATE-SUPPORTED HIGHER EDUCATION AMONG NEGROES IN THE STATE OF FLORIDA by LEEDELL W. NEYLAND TATE-SUPPORTED HIGHER EDUCATION among Negroes in s Florida had its beginning during the decade of the 1880’s. The initial step in this new educational venture was taken by Governor William D. Bloxham who, during his first administra- tion, vigorously set forth a threefold economic and social program. In his inaugural address he declared that in order to promote the interest, welfare, and prosperity of the state, “we must in- vite a healthy immigration; develop our natural resources by se- curing proper transportation; and educate the rising generation.’’ 1 He promulgated this combination as “the three links in a grand chain of progress upon which we can confidently rely for our future growth and prosperity.’’ 2 During his four years in office, 1881-1885, Governor Blox- ham assidiously endeavored to implement his inaugural pledges. -

2013-2015 Catalog

2013-2015 2011-2013 CATALOG N COMMUNITY CO COMMUNITY N L O C COPIAH-LIN EGE LL 2013 - 2015 COPIAH-LINCOLN COMMUNITY COLLEGE CATALOG 39191 PAID US Postage Wesson, MS Wesson, Permit No. 20 Non-Profit Org. Address Service Requested P.O. Box 649 • Wesson, MS 39191 MS Wesson, • 649 Box P.O. 1 COPIAH-LINCOLN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 99th - 100th ANNUAL SESSIONS Announcements for 2013-2015 Wesson Campus Natchez Campus Simpson County Center . THE PLACE TO BE 2 DIRECTORY OF INFORMATION Copiah-Lincoln Community College Wesson Campus P.O. Box 649 (Mailing Address) 1001 Copiah Lincoln Lane (Physical Address) Wesson, MS 39191 Telephone: (601) 643-5101 Copiah-Lincoln Community College Copiah-Lincoln Community College Natchez Campus Simpson County Center 11 Co-Lin Circle 151 Co-Lin Drive Natchez, MS 39120 Mendenhall, MS 39114 Telephone: (601) 442-9111 Telephone: (601) 849-5149 E-mail addresses can be found at our website: www.colin.edu AFFILIATIONS Copiah-Lincoln Community College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award Associate in Arts and Associate in Applied Science degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Copiah-Lincoln Community College. The commission is only to be contacted if there is evidence that appears to support an institution’s significant non-compliance with a requirement or standard. All normal inquiries about the institution, such as admission requirements, financial aid, educational programs, and other college-related information should be addressed directly to the College and not to the office of the Commission on Colleges. -

93Rd ANNUAL SESSIONS

1 COPIAH-LINCOLN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 92nd - 93rd ANNUAL SESSIONS Announcements for 2011-2013 Wesson Campus Natchez Campus Simpson County Center . THE PLACE TO BE 2 DIRECTORY OF INFORMATION Copiah-Lincoln Community College Wesson Campus P.O. Box 649 Wesson, MS 39191 Telephone: (601) 643-5101 Copiah-Lincoln Community College Copiah-Lincoln Community College Natchez Campus Simpson County Center 11 Co-Lin Circle 151 Co-Lin Drive Natchez, MS 39120 Mendenhall, MS 39114 Telephone: (601) 442-9111 Telephone: (601) 849-5149 E-mail addresses can be found at our website: www.colin.edu AFFILIATIONS Copiah-Lincoln Community College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia, 30033-4097; Telephone number (404) 679-4501 (www.sacscoc.org) to award Associate in Arts and Associate in Applied Science degrees. Copiah-Lincoln is also an active member of the American Association of Community Colleges, the Mississippi Association of Community and Junior Colleges, the Mississippi Association of Colleges, and the Southern Association of Community and Junior Colleges. ****************** It is the policy of Copiah-Lincoln Community College to make available its teaching and service programs and its facilities to every qualified person. Copiah-Lincoln Community College does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability, religion, age, or other factors prohibited by law in any of its educational programs, activities, admission, or employment practices. All complaints in regard to Title IX directives should be made to the Title IX Coordinator, Dr. Brenda Orr at P.O. Box 649, Wesson, MS 39191, (601) 643-8671. -

Community, Technical, and Junior College Statistical Yearbook, 1988 Edition, INSTITUTION American Association of Community and Junior Colleges, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 307 907 JC 890 262 AUTHOR Palmer, Jim, Ed. TITLE Community, Technical, and Junior College Statistical Yearbook, 1988 Edition, INSTITUTION American Association of Community and Junior Colleges, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 74p.; For an appendix to the yearbook, see JC 890 263. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) Statistical Data (110) EDPS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administrators; *College Faculty; Community Colleges; Community Education; Degrees (Academic); *Enrollment; Fees; Full Time Students; Institutional Characteristics; Minority Groups; National Surveys; cart Time Students; Private Colleges; Public Colleges; Statistical Data; Statistical Surveys; Tuition; *Two Year Colleges; *Two Year College Students ABSTRACT Drawing primarily from a survey conducted by the American Association of Community and Junior Colleges in f.11 1987, this report provides a statistical portrait of the country's community, junior, and technical colleges on a state-by-state and institution-by-institution basis. Part 1 presents data for individual colleges listed by state. For each college, it provides the following information: the name, city, and zip code of the institution; the name of the chief executive officer; type of control (i.e., public or private); fall 1986 and 1987 headcount enrollment in credit classes of full-time, part-time, and minority students; noncredit enrollment for 1986-87; number of full- and part-time faculty teaching credit classes in fall 1987; number of administrators employed in fall 1987; and annual tuition and required fees for the 1987-88 academic year. Part 2 presents statewide data on both public and private two-year colleges. Tha state summaries include the number of colleges; fall 1986 and 1987 full- and part-time and total headcount enrollment in credit classes; fall 1987 minority enrollment in public institutions; and the numbers of faculty employed full- and part-time in fall 1987.