Reminiscences by Emory Fisk Skinner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The U.F.A. to Social Progress the U

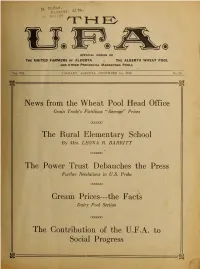

Federal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA The ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, NOVEMBER 1st,, 1928 No. 25 News from the Wheat Pool Head Office Grain Trade's Fictitious ''Average' Prices The Rural Elementary School By Mrs. LEONA R. BARRITT The Power Trust Debauches the Press Further Revelations in U.S. Probe Cream Prices- --the Facts Dairy Pool Section The Contribution of the U.F.A. to Social Progress THE U. F. A. November 1st, 1036 $7,600.00CashPrizes/ WILL BE GIVEN AWAY BY The Nor*- West Farmer In Simple Fascinating Compttition FOR YOU! m-Can You Find The" Twins''?^ FIndrhvmt Survyvucaa* They •tM*ok attkc. y«u M^f WImm* NoiBoftitil They arc not sU dttfliftJ the turn* Many young ladU* look alik* and (hv rlghirvn on ihta p*f l*ok like evcli other, but the "TWINS" are dretaed eiarily the aame. like all real rwina Now look •O'n sbowc the hart? TriaunM^ U difTereni. Un't tt> Thaf'a Hh«rc the fun mme« In. ftndlng the Twlna It take* real care and cleverncaa to point out Che diflercnce ai»d ftii4 cIm twm f««l ''t'TNS,*' baOMM tw« and oal|' iwo ar« ManticaUy Uio aame. ' ' CLUES ' ' Ar flfsc ftlanca, all tba yomm* ladle* look alike •ut YOU ARE ASK.eD TO ftSB THE "TWINS" THAT ARE (XOTHtl) F.XACTl Y ALIKE. Now then, upon clo**r e&annlnatioH, you wlU Umd a 4iffcraace In their wearing apparel. Have ihey all earring* or necklace* t How about their Kata f Arc lhay trkcuned the aame ? Some ha«e band* on the brim aad crowaa; ethara kava Mt. -

Naturalization Documents and Filings

Bonner County Naturalization Documents 1 NATURALIZATION DOCUMENTS AND FILINGS NAME CERTIFIED PAGE DOCUMENT TYPE AND INFO # # Adamo, 545 444 PETITION FOR NATURALIZATION: Gesualdo Occupation: Beer Parlor Adams, Gesualdo Birth: 10/14/1891 Altilia, Italy Description: Male Brown/Gray 5’ 6” 170 lbs Adams, Ward Nationality: Italian North Race: White Spouse: Mildrid Spouse Birth: 12/12/1912 Chicago, IL Married: 11/17/1939 Kalispell, MT Children: 1 Edward James 12/18/1925 Cheney, WA Port of Departure: Naples, Italy Date of Arrival: 05/25/1904 Ship: Konigis louise Port of Arrival: New York, NY Notation: Petition states Cancelled for want of Prosecution and name changed to Ward Adams Adams, Gesualdo 545 443 Affidavits of Witnesses From Arno F Eckert stating he has known Gesualdo has lived in the US from 01/01/1939 to 10/04/1943 Adams, Gesualdo 545 444 PETITION FOR NATURALIZATION: Adamo, Occupation: Beer Parlor Gesualdo Birth: 10/14/1891 Altilia, Italy Description: Male Brown/Gray 5’ 6” 170 lbs Adams, Ward Nationality: Italian North Race: White Spouse: Mildrid Spouse Birth: 12/12/1912 Chicago, IL Married: 11/17/1939 Kalispell, MT Children: 1 Edward James 12/18/1925 Cheney, WA Port of Departure: Naples, Italy Date of Arrival: 05/25/1904 Ship: Konigis louise Port of Arrival: New York, NY Notation: Petition states Cancelled for want of Prosecution and name changed to Ward Adams Adams, Ward 545 446 Letter Adamo, Gesuldo Lost Alien Registration Receipt Card Bonner County Naturalization Documents 2 Adams, Ward 545 444 PETITION FOR NATURALIZATION: Adams, -

American Military History: a Resource for Teachers and Students

AMERICAN MILITARY HISTORY A RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS PAUL HERBERT & MICHAEL P. NOONAN, EDITORS WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY WALTER A. MCDOUGALL AUGUST 2013 American Military History: A Resource for Teachers and Students Edited by Colonel (ret.) Paul H. Herbert, Ph.D. & Michael P. Noonan, Ph.D. August 2013 About the Foreign Policy Research Institute Founded in 1955 by Ambassador Robert Strausz-Hupé, FPRI is a non-partisan, non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. In the tradition of Strausz-Hupé, FPRI embraces history and geography to illuminate foreign policy challenges facing the United States. In 1990, FPRI established the Wachman Center, and subsequently the Butcher History Institute, to foster civic and international literacy in the community and in the classroom. About First Division Museum at Cantigny Located in Wheaton, Illinois, the First Division Museum at Cantigny Park preserves, interprets and presents the history of the United States Army’s 1st Infantry Division from 1917 to the present in the context of American military history. Part of Chicago’s Robert R. McCormick Foundation, the museum carries on the educational legacy of Colonel McCormick, who served as a citizen soldier in the First Division in World War I. In addition to its main galleries and rich holdings, the museum hosts many educational programs and events and has published over a dozen books in support of its mission. FPRI’s Madeleine & W.W. Keen Butcher History Institute Since 1996, the centerpiece of FPRI’s educational programming has been our series of weekend-long conferences for teachers, chaired by David Eisenhower and Walter A. -

Wooldridge Steamboat List

Wooldridge Steamboat List Vessel Name Type Year [--] Ashley 1838 [--] McLean (J.L. McLean) 1854 A. Cabbano Side Wheel Steamboat 1860 A. Fusiler (A. Fuselier) 1851 A. Fusiler (A. Fusilier) 1839 A. Gates Side Wheel Towboat 1896 A. Giles Towboat 1872 A. McDonald Stern Towboat 1871 A. Saltzman Stern Wheel Steamboat 1889 A.B. Chambers Side Wheel Steamboat 1855 A.B. Shaw 1847 A.C. Bird Stern Wheel Steamboat 1875 A.C. Goddin 1856 A.D. Allen Stern Wheel Steamboat 1901 A.D. Hine (Ad Hine) 1860 A.D. Owens Stern Wheel Steamboat 1896 A.D. Taylor Side Wheel Steamboat A.G. Brown Side Wheel Steamboat 1860 A.G. Henry Stern Wheel Steamboat 1880 A.G. Mason Stern Wheel Steamboat 1855 A.G. Ross Stern Wheel Steamboat 1858 A.G. Wagoner Snagboat 1882 A.H. Seviers 1843 A.H. Seviers (A.H. Sevier) 1860 A.J. Sweeny (A.J. Sweeney) Stern Wheel Steamboat 1863 A.J. Baker Towboat 1864 A.J. White Side Wheel Steamboat 1871 A.J. Whitney Stern Towboat 1880 A.L. Crawford Stern Wheel Steamboat 1884 A.L. Davis 1853 Tuesday, June 28, 2005 Page 1 of 220 Vessel Name Type Year A.L. Gregorie (A.L. Gregoire) Ferry 1853 A.L. Mason Stern Wheel Steamboat 1890 A.L. Milburn 1856 A.L. Norton Stern Wheel Steamboat 1886 A.L. Shotwell Side Wheel Steamboat 1852 A.M. Jarrett Stern Wheel Steamboat 1881 A.M. Phillips Side Wheel Steamboat 1835 A.M. Scott Screw Tunnel 1906 A.N. Johnson Side Wheel Steamboat 1842 A.O. Tyler Side Wheel Steamboat 1857 A.R. -

Ellen Dawson

23 Chapter One – Ellen Dawson: “The Little Orphan of the Strikers” Ellen Dawson was a woman of fascinating contradictions – small and frail, yet a fearless fighter; stoic, yet a charismatic stump speaker: devout Catholic, yet a dedicated communist labor activist. In many ways, her life is representative of millions of immigrant American workers. Born into working class poverty, she was a victim of social and economic inequities that valued the wealth and power of a few over the welfare of the many. Raised in an environment of violent labor unrest, she was nurtured with socialist ideas that offered alternatives to capitalism. Forced to abandon her native Scotland in order to survive, she migrated first to England and then across the Atlantic in search of employment opportunity. In the United States, she helped organize and lead unskilled textile workers against abuses perpetuated by conspiracies of industrialists, government officials and trade unionists. When her revolutionary efforts failed, she retreated into the safety of silence and anonymity. Beyond all this, and perhaps most importantly, this is the story of one woman and her struggle to make the world a better place. Ellen’s life began during the closing days of the Victorian era, in a decaying, two-room tenement in Barrhead,1 a grim, smog-filled industrial village on the southwestern fringe of Glasgow. It was three o’clock in the morning on Friday, 24 December 14, 1900,2 eleven days before Christmas in a Scotland where Christmas was not yet a workers’ holiday.3 The day was chilly, with winds near gale force. -

– Fashions of the Titanic Era –

SECTION C THE STATE JOURNAL Ap RiL 15, 2012 Spectrum El EgancE and OpulEncE – Fashions of the Titanic Era – By Beth Caffery Carter Curator of ColleCtions When and liberty Hall HistoriC site Where to Go hen the Titanic set out on its “Elegance & Opulence: Fashions of the maiden voyage, the ship car- Titanic Era” from Liberty Hall Historic Site ried 324 first-class passen- gers. These were members of Collections is on exhibit at the Orlando BritishW and American high society, and 145 Brown House, 202 Wilkinson St., through of them were women. They were of an up- June 23 and is free admission. The hours per class that lived a life of leisure and were are Tuesday-Saturday, 10a.m.-4:30 p.m. aware of conspicuous con- sumption, or buying goods mainly for dis- great deal about what people playing wealth. she socialized with, what With 2012 people were wearing, and marking the what she purchased. 100th anni- She wrote about versary of the buying a dress in Italy sinking of Ti- in May 1908: “I com- tanic, Liberty mitted the indiscre- Hall Historic tion a week ago of hav- Site will be ex- ing – or rather begin- hibiting several ning to have – a white of the gowns linen dress made. Lil is that belonged also having one so we to the Brown go together for the fit- family dur- tings & oh the worry of it ing this era for they are never ready and show how and our precious time is a woman of so- wasted…” ciety from Frank- Mary Yoder Brown Scott fort would have traveled back to New York dressed, particularly on from Liverpool in July 1908 their own ocean sail- aboard the White Star Line SS ing trips to Europe, in Baltic. -

American Military History

AMERICAN MILITARY HISTORY A RESOURCE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS PAUL HERBERT & MICHAEL P. NOONAN, EDITORS WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY WALTER A. MCDOUGALL AUGUST 2013 American Military History: A Resource for Teachers and Students Edited by Colonel (ret.) Paul H. Herbert, Ph.D. & Michael P. Noonan, Ph.D. August 2013 About the Foreign Policy Research Institute Founded in 1955 by Ambassador Robert Strausz-Hupé, FPRI is a non-partisan, non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. In the tradition of Strausz-Hupé, FPRI embraces history and geography to illuminate foreign policy challenges facing the United States. In 1990, FPRI established the Wachman Center, and subsequently the Butcher History Institute, to foster civic and international literacy in the community and in the classroom. About First Division Museum at Cantigny Located in Wheaton, Illinois, the First Division Museum at Cantigny Park preserves, interprets and presents the history of the United States Army’s 1st Infantry Division from 1917 to the present in the context of American military history. Part of Chicago’s Robert R. McCormick Foundation, the museum carries on the educational legacy of Colonel McCormick, who served as a citizen soldier in the First Division in World War I. In addition to its main galleries and rich holdings, the museum hosts many educational programs and events and has published over a dozen books in support of its mission. FPRI’s Madeleine & W.W. Keen Butcher History Institute Since 1996, the centerpiece of FPRI’s educational programming has been our series of weekend-long conferences for teachers, chaired by David Eisenhower and Walter A. -

A Century at Sea Jul

Guernsey's A Century at Sea (Day 2) Newport, RI Saturday - July 20, 2019 A Century at Sea (Day 2) Newport, RI 500: Ship's Medicine Case, c. 1820 USD 800 - 1,200 Mahogany ship's medicine case with brass fittings. Features nine (9) apothecary bottles still containing some original tinctures and ointments. Bottom drawer contains glass motor and pestle. Circa 1820. Dimensions 7.5" tall x 6" deep x 7" wide Condition: More detailed condition reports and additional photographs are available by request. The absence of a condition report does not imply that the lot is in excellent condition. Please message us through the online bidding platform or call Guernsey's at 212-794-2280 to request a more thorough condition report. 501: Nautical Octant, Nineteenth Century USD 800 - 1,200 Octant with ebony and bone inserts, in original wooden box with brass latch and fittings, circa the nineteenth century. Dimensions: 11" long Condition: Excellent condition. More detailed condition reports and additional photographs are available by request. The absence of a condition report does not imply that the lot is in excellent condition. Please message us through the online bidding platform or call Guernsey's at 212-794-2280 to request a more thorough condition report. 502: USS Richard L. Page Christening Bottle USD 800 - 1,000 Wooden box containing a christening bottle. The box reads –Christening Bottle USS Richard L. Page Miss Edmonia L. Whittle Co-sponsor, Launched 4 April 1966, Bath Iron works Corporation, Bath, Maine"The USS Richard L. Page was a Brook class frigate in the Navy serving as a destroyer escort. -

Acs Ilene 9, from Rojtok Travelled on the SS Pennsylvania from Hamburg

Radi Berta 20, from Tasnodesany travelled on the SS Vaderland from Antwerp to NY arriving on Oct 23, 1911. Left mother Radi Samuelne? in Tamadesany, coming to Trenton, NJ to see uncle ? Buzgo. Birthplace: Tasmadeseny Radich John , from leaving Klingenbach, Austria; lives in South Bend travelled on the SS Reliance from Hamburg to NY arriving on Dec 10, 1926. Coming to South Bend to see home. Birthplace: Radich Maria 21, from Klingenbach, Austria travelled on the SS Reliance from Hamburg to NY arriving on Dec 10, 1926. Left mother Maria Dimlich in Klingenbach, coming to South Bend to see Home. Birthplace: Klingenbach, Austria Radics Elisabeth , from Kelenpatak, Hungary travelled on the SS La Touraine from to arriving on 2739. Left grandmother Apolonia Hartmann in Kelenpatak coming to see father Radics Istvan. Birthplace: Kelenpatak (= Klingenbach, Austria0 Radics Johann 16, from Kelenpatak, Hungary travelled on the SS La Touraine from to arriving on 2739. Left grandmother Apolonia Hartmann in Kelenpatak coming to see father Radics Istvan. Birthplace: Kelenpatak (= Klingenbach, Austria0 Radics Maria 11, from Kelenpatak, Hungary travelled on the SS La Touraine from to arriving on 2739. Left grandmother Apolonia Hartmann in Kelenpatak coming to see father Radics Istvan. Birthplace: Kelenpatak (= Klingenbach, Austria0 Radics Stephen 7, from Kelenpatak, Hungary travelled on the SS La Touraine from to arriving on 2739. Left grandmother Apolonia Hartmann in Kelenpatak coming to see father Radics Istvan. Birthplace: Kelenpatak (= Klingenbach, Austria0 Radovan Maria 23, from Udvard travelled on the SS Nieuw Amsterdam from Rotterdam to NY arriving on Jul 9, 1912. Left Father John Radovan in Udvard, coming to South Bend to see Brother-in-law Steve Buszczky. -

FOIA Control

FOIA Control Number Date Rec'd Unit Name Description COMPANY NAME 8/27/2011 20114025 SEC Charleston All photographs pertaining to the recovery of the TowBoat US- Charleston 65'POWER vessel that sunk 8/29/2011 20113649 INV MISLE case number 561035 TowBoatUS Savannah 8/29/2011 20113650 INV T/V BUSTER BOUCHARD- Minimal Spill of Diesel Oil at Royston Rayzor Vickery & Williams, LLP Bollinger Shipyard 8/29/2011 20113651 NVDC Copies of documentation certificate for vessel "Ariel" Bruce Flenniken 8/29/2011 20113652 NMC Merchant Mariner Records Maria Lay 8/29/2011 20113653 NMC Merchant Mariner Records Marta Perez 8/29/2011 20113654 NMC Merchant Mariner Records Delia Roork 8/29/2011 20113655 NMC Merchant Mariner Records Mary E. Glod 8/29/2011 20113656 INV Copies of the USCG detentional deficiencies file concerning Casey & Barnett LLC the M/V GREEN MAJESTIC'S 8/29/2011 20113657 INV Info regarding XXXXXXXX allegedly injured her foot while Walters Nixon Group, INC disembarking the WHALE WATCHER 8/29/2011 20113658 INV M/V JAMES F NEAL- 10/21/09 collision, Activity No. Schroeder, Maundrell, Barbiere & Powers 3630379 8/29/2011 20113659 INV All info pertaining to the search for XXXXXXXX the rescue Tucker Vaughan Gardner & Barnes of XXXXXXXXXX 8/29/2011 20113660 INV Info regarding the incident with two vessels on 8/3/11, McGuinn, Hillsman & Palefsky Minh Troung , who was killed in the collision 8/29/2011 20113665 VTS Houston/Galveston PAWSS, VHF-FM ch 12 and 13 replay recordings, Transit Eastham Watson Dale & Forney, LLP Logs 8/29/2011 20113666 D8 Legal Historical Oil Spill information Department of Geography and Anthropology 8/29/2011 20113706 NVDC Info on vessel KILOHANA Mimi Bornhorst 8/29/2011 20113708 NVDC Info on vessel BEANS and ESPRESSO Pacific Maritime Title 8/29/2011 20113709 NVDC Info on vessel PATRICE Ala Wai Yacht Brokerage 8/29/2011 20113719 INV SAR & investigation records pertaining to M/V SEA WATCH Bird Bird & Hestres, P.S.C. -

Travel & Exploration Cruise Ship Memorabilia – Cartography

Sale 449 Thursday, March 10, 2011 1:00 PM Rare Americana – Travel & Exploration Cruise Ship Memorabilia – Cartography Auction Preview Tuesday, March 8, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wedesnsday, March 9, 9:00 am to 3:00 pm Thursday, March 10, 9:00 am to 1:00 pm Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material.