"Changing Tracks and Charting New Territories: the 'Train' Motif in Bengal Partition Stories of 1947"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

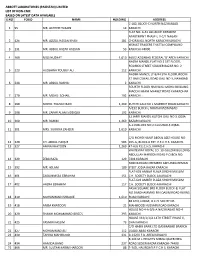

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Assessment of Ground Water Quality at Selected Locations Inside Karachi City

Pak. J. Chem. 5(3): 138-145, 2015 Full Paper ISSN (Print): 2220-2625 ISSN (Online): 2222-307X DOI: 10.15228/2015.v05.i03.p06 Assessment of Ground Water Quality at Selected Locations Inside Karachi City *S. M. S. Nadeem, S. Masood, B. Bano, Z. A. Pirzadaa, M. Ali *Department of Chemistry, University of Karachi, Pakistan. aDepartment of Microbiology, University of Karachi, Pakistan. E-mail: *[email protected] ABSTRACT The physico-chemical and microbiological water quality parameters of ground water samples from different locations inside Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town, Karachi were analyzed by standard methods of analysis. The drinking water quality parameters such as pH, Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), Electrical conductance (EC) and concentration of important minerals such as Calcium (Ca2+) 2+ + + - 2- Magnesium (Mg ), Sodium (Na ), Potassium (K ), Chloride (Cl ), and Sulphate (SO4 ) in ground water samples was determined and the experimental values were compared with the World Health Organization (WHO) and Pakistan Standard and Quality Control Authority (PSQCA) standards to evaluate the feasibility of ground water samples to be used as drinking water. The physico-chemical parameters of 90% ground water samples were found to be in compliance with WHO and PSQCA drinking water quality standards whereas microbiological characteristics of 70% of ground water samples were found satisfactory enough to permit there use as potable water. Keywords: Gulshan-e-Iqbal; WHO; PSQCA; Total Dissolved Solids; Physico-chemical 1. INTRODUCTION Ground water is that water which perforates through the layers of soil and saturates the underground rocks and sediments. Ground water is one of our most vital natural resources as it can serve as a source of drinking water, for irrigation of crops and as domestic water for household use. -

TCS Offices List.Xlsx

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Hyderabad TCS Office Agriculture Shop # 12 Agricultural Complex Hyderabad 0316-9992350 2 Hyderabad TCS Office Rabia Square SHOP NO:7 RABIA SQUARE HYDER CHOCK HYDERABAD SINDH PAKISTAN 0316-9992351 3 Hyderabad TCS Office Al Noor Citizen Colony SHOP NO: 02 AL NOOR HEIGHTS JAMSHORO ROAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992352 4 Hyderabad TCS Office Qasimabad Opposite Larkana Bakkery RIAZ LUXURIES NEAR CALTEX PETROL PUMP MAIN QASIMABAD ROAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992353 5 Hyderabad TCS Office Market Tower Near Liberty Plaza SHOP NO: 26 JACOB ROAD TILAK INCLINE HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992354 6 Hyderabad TCS Office Latifabad No 07 SHOP NO" 01 BISMILLAH MANZIL UNIT NO" 07 LATIFABAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992355 7 Hyderabad TCS Office Auto Bhan Opposite Woman Police Station Autobhan Road near women police station hyderabad 0316-9992356 8 Hyderabad TCS Office SITE Area Area Office Hyderabad SITE Autobhan road near toyota motors site area hyderabad 0316-9992357 9 Hyderabad TCS Office Fatima Height Saddar Shop No.12 Fatima Heights Saddar Hyderabad 0316-9992359 10 Hyderabad TCS Office Sanghar SHOP NO: 02 BAIT UL FAZAL BUILDING M A JINNAH ROAD SANGHAR 0316-9992370 11 Hyderabad TCS Office Tando allah yar SHOP NO: 02 MAIN BUS STOP NEAR NATIONA BANK TDA 0316-9992372 12 Hyderabad TCS Office Nawabshah Near PTCL SUMERA PALACE HOSPITAL ROAD NAAWABSHAH 0316-9992373 13 Hyderabad TCS Office Tando Muhammad Khan AL FATEH CHOCK ADJUCENT HABIB BANK STATION ROAD TANDO MOHD KHAN 0316-9992374 14 Hyderabad TCS Office Umer Kot JAKHRA MARKET -

Progressive Urdu Poetry

Carlo Coppola. Urdu Poetry, 1935-1970: The Progressive Episode. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. 702 pp. $45.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-19-940349-3. Reviewed by S. Akbar Hyder Published on H-Asia (July, 2018) Commissioned by Sumit Guha (The University of Texas at Austin) Carlo Coppola’s 1975 dissertation submitted of us implored Coppola to publish his dissertation to the University of Chicago’s Committee on Com‐ as a book; the result is Urdu Poetry, 1935-1970: parative Studies in Literature under the supervi‐ The Progressive Episode. Der āyad durast āyad (a sion of C. M. Naim was no ordinary thesis: it was a Perso-Urdu saying that suggests better late than meticulously researched and thoughtfully crafted never). work of modern South Asian literary history, with The book comprises twelve chapters, two ap‐ a focus on the frst four decades of the Urdu Pro‐ pendices, a chronology, and a glossary. The frst gressive movement (the taraqqī pasañd tahrīk). chapter provides a concise historical overview of This movement, especially during its formative nineteenth-century colonial-inflected socioreli‐ years in the 1930s and the 1940s, nudged writers gious reform movements and their impact on the and other artists out of their world of conformity, literary sensibilities of the twentieth century. The especially in terms of class consciousness, reli‐ second chapter treats the fery collection of Urdu gious and national allegiances, and gender roles. prose, Añgāre (Embers), the sensational impact of When Coppola submitted his dissertation, there which far outpaced its aesthetic merits. The third was simply no work, in Urdu or in English, that and fourth chapters are a diligent documentation could compare to this dissertation’s sweeping and and narrative of the Progressive Writers’ Associa‐ balanced coverage of a movement that resonated tion, the literary movement—with its calls to jus‐ not just in written literature but also in flms, po‐ tice and accountability—that is at the crux of this litical assemblies, mass rallies, and calls for justice study. -

Communal Violence and Literature

Communal Violence and Literature T flood of communal violence came with all its evils and left, but it left a pile of living, dead, and gasping corpses in its wake. It wasn’t only that the country was split in two, bodies and minds were also divided. Moral beliefs were tossed aside and humanity was in shreds. Government officers and clerks along with their chairs, pens and inkpots, were dis- tributed like the spoils of war. And whatever remained after this division was laid to waste by the benevolent hands of communal violence. Those whose bodies were whole had hearts that were splintered. Families were torn apart. One brother was allotted to Hindustan, the other given over to Pakistan; the mother was in Hindustan, her offspring were in Pakistan; the husband was in Hindustan, his wife was in Pakistan. The bonds of human relationships were in tatters, and in the end many souls remained behind in Hindustan while their bodies started off for Pakistan. Communal violence and freedom became so muddled that it was dif- ficult to distinguish between the two. Anyone who obtained a measure of freedom discovered violence in its wake. The storm struck without any warning so people couldn’t even gather their belongings. When things cooled down a bit people collected themselves and had a chance to observe what was going on around them. With every aspect of life disturbed by this earthshaking event, how could poets and writers possibly sit on the side without saying a word? How could literature, which bears close ties to life, avoid getting its shirt- front wet when life was drenched in blood? Thus, forgetting the struggles of love and separation, people concentrated on saving their skin and bones. -

Branch Directory

Dubai Islamic Bank - Branch Directory Abbottabad S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Khyber 1 31 Abbottabad CB 306/4, Lala Rukh Plaza, Mansehra Road, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342239-41 Ground Floor, Shop Nos.12 & 13, Mamu Jee Market, Opp GPO, Cantt Khyber 2 161 Abbottabad 2 Bazaar, Abbottabad, Pakhtunkhwa 0992-342394 Attock S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Plot No B-1-63, A Block, Khan Plaza, Fawara Chowk, Civil Bazaar, Attock. 3 73 Attock Punjab. Punjab 057-2702054-6 Mehria Town Housing Scheme, Phase 1, Shop No. 25 + 39, Block - A, Kamra 4 187 Mehria Road - Attock Punjab Bahawalpur S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Model Town Plot No 12.B, Khewat No 148,Khatooni No.246,General Officer Colony, 062-2889951-3, 5 71 Bahawalpur Model Town B, Bahawalpur,Punjab. Punjab 2889961-3 Burewala S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number 439/EB, Block C, Al-Aziz Super Market, College Road, Burewala. Vehari 6 95 Burewala District, Punjab. Punjab 067-3772388 Chakwal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, No. 1636, Khewat 323, Opposite Main PTCL Office Main 7 172 Chakwal Talagang Road, Chakwal District, Punjab. Punjab 054-3544115 Chaman S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Haji Ayub Plaza, Plot No. Mall Road, Chaman.Killa Abdullah 8 122 Chaman District, Balochistan . Balochistan 0826-61806-61812 Dadyal S.No Branch Code Branch Name Address Province PABX Number Ground Floor, Khasra No. 552, Moza Mandi, Kacheri Road, Dadyal, District Azad Jammu & 9 120 Dadyal Mirpur Azad Jammu Kashmir. -

Magazine-2-3 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 (PAGE 3) SACRED SPACE FORBEARANCE helps face difficulties How to be a failure? Akhtar Ul-nisa it to grow strong and pure we need to be regular in our spiritual practices and assert our Ankush Sharma stories", nobody gives a damn to the "failure stories". But it Forbearance is the ability to respond to a independence from the desire in the mind. It needs must not be ignored that the failed people have faced multi- situation of failure, disappointment, pain patience, presence, grace and focus. Failure! Yes, you have read right. This write-up will surf dimensional hurdles in their struggle and are more experi- you through the various paths leading to the failure. It may enced compared to the toppers especially those who got suc- or conflict with understanding and Significance of forbearance seem absurd but believe me, it would make sense in a few cess early. It is not to say that the toppers are not insightful minutes read. In fact, it has something crucial to offer to rather what I mean is that some people have inbuilt brilliance The quality of forbearance is of the highest importance composure. those who are aspiring to achieve success in their lives. or a good schooling background which might not be every- to every human being. Forbearance and nonviolence are It is bearing the physical, mental and emotional pain Success may have different meanings to different people but one's case. So, it's the failed people who can actually eluci- manifestation of inner strength. Reactivity and retaliation with strong and steady faith without lamenting or worry- the paths leading there have a common and a simple princi- date the worst struggle scenarios and impediments allowing make us to lose precious energy, forbearance on the other ing. -

In the Heat of Fratricide: the Literature of India's Partition Burning Freshly (A Review Article)

In the Heat of Fratricide: The Literature of India’s Partition Burning Freshly (A Review Article) India Partitioned: The Other Face of Freedom. Edited by M H. volumes. New Delhi: Lotus, Roli Books, . Orphans of the Storm: Stories on the Partition of India. Edited by S C and K.S. D. New Delhi: UBSPD, . Stories about the Partition of India. Edited by A B. volumes. Delhi: Indus, HarperCollins, . I This is not that long awaited dawn … —Faiz Ahmad Faiz T surrounding the Partition of India on August –, created at least ten million refugees, and resulted in at least one million deaths. This is, perhaps, as much as we can quantify the tragedy. The bounds of the property loss, even if they were known, could not encompass the devastation. The number of persons beaten, maimed, tortured, raped, abducted, exposed to disease and exhaustion, and other- wise physically brutalized remains measureless. The emotional pain of severance from home, family and friendships is by its nature immeasur- able. Fifty years have passed and the Partition remains unrequited in the historical experience of the Subcontinent. This is, in one sense, as it should be, for the truth remains that the Partition unleashed barbarism so cruel, indeed so thorough in its cruelty, and complementary acts of compassion so magnificent—in short a com- • T A U S plex of impulses so pernicious, so heroic, so visceral, so human—that they cannot easily be assimilated into normal life. Neither can they be forgot- ten. And so, ingloriously, the experience of the Partition has been perhaps most clearly assimilated in the perpetuation of communal hostility within both India and Pakistan, for which it serves as the defining moment. -

The 40Th Annual Conference on South Asia (2011)

2011 40th Annual Conference on South Asia Paper Abstracts Center for South Asia University of Wisconsin - Madison Aaftaab, Naheed Claiming Middle Class: Globalization, IT, and exclusionary practices in Hyderabad In this paper, I propose that middle class identity in the IT sector can be read as part of an “identity politics” that claim certain rights and benefits from governmental bodies both at the national and international levels. India’s economic growth since the 1991 liberalization has been attended by the growth of the middle classes through an increase in employment opportunities, such as those in the IT sector. The claims to middle class status are couched in narratives of professional affiliations that shape culturally significant components of middle class identities. The narratives rely on the ability of IT professionals to reconcile the political identities of nationalism while simultaneously belonging to a global work force. IT workers and the industry at large are symbols of India’s entry into the global scene, which, in turn, further reinforces the patriotic and nationalist rhetoric of “Indianness.” This global/national identity, however, exists through exclusionary practices that are evident in the IT sector despite the management’s assertions that the industry’s success is dependent on “merit based” employment practices. Using ethnographic data, I will examine middle class cultural and political claims as well as exclusionary practices in professional settings of the IT industry in order to explore the construction of new forms of identity politics in India. 40th Annual Conference on South Asia, 2011 1 Acharya, Anirban Right To (Sell In) The City: Neoliberalism and the Hawkers of Calcutta This paper explores the struggles of urban street vendors in India especially during the post liberalization era. -

Download Volume VI Issue 1

1 Contents About the volume...........................................................................................3 Compiling Records Kasaba Ganpati Temple, Pune Parag Narkhede..............................................................................................5 Budaun ‘Piranshahr’: The city of saints Jinisha Jain.....................................................................................................14 Methods and Approaches Natural heritage and cultural landscapes: Understanding Indic values Amita Sinha...................................................................................................23 History: a responsible story Surbhi Gupta.................................................................................................29 Visual documentation as a tool for conservation: Part I, North Chowringhee Road, Kolkata Himadri Guha, Biswajit Thakur, Swaguna Datta...................................35 Dholavira: Ancient water harnessing system Swastik Harish..............................................................................................53 Havelis and chhattas of Saharanpur O C Handa ....................................................................................................59 Post independence growth of Delhi: A legal perspective Panchajanya Batra Singh.............................................................................67 Aaraish-e-Balda: Planning open spaces and water bodies Sajjad Shahid ...............................................................................................75 -

Soneri Bank Limited LIST of DESIGNATED BRANCHES OPEN on SATURDAYS

Soneri Bank Limited LIST OF DESIGNATED BRANCHES OPEN ON SATURDAYS Branch S.No Branch Name City Province Address Phone Number Code Shop No: 11, Ground Floor, Poonawala 1 0098 NAPIER ROAD BRANCH KARACHI Sindh 021-32713539 Trade Tower, Napier Road, Karachi Shop No: 1, 2, 3 & 12, Saify Market, Survey: NEW CHALLI BRANCH, 2 0067 KARACHI Sindh 46, SR:7, Main Shahrah-e-Liaquat, Serai 021-32625246/32625279 KARACHI Quarters, Karachi Shop No: G-3, Plot No: R.B.10/14, III-A-208, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, 3 0041 KARACHI Sindh Near Radio Pakistan, M. A. Jinnah Road, 021-32213498 KARACHI Karachi TIMBER MARKET Plot No: 1490 & 1491, Jinnahabad, Lyari 4 0185 KARACHI Sindh 021-32742492-3 BRANCH Quarters, Timber Market, Karachi Shop Nos: F/4 & F/5, Mall Square, Plot No: 5 0038 ZAMZAMA BRANCH KARACHI Sindh Zam-1, Zamzama Boulevard, Phase-V, 021-35375837 Defence Housing Authority, Karachi Progressive Centre, Plot No: 30-A, Survey SHAHRAH-E-FAISAL 6 0031 KARACHI Sindh Sheet No: 35-P/1, Block-6, P.E.C.H.S., 021-34535553-4 BRANCH Shahrah-e-Faisal, Karachi Crown Centre, Ground Floor, SB-01, Block GULSHAN-E-IQBAL 7 0034 KARACHI Sindh No: 13-C, (KDA Scheme No: 24), Gulshan-e- 02134811831-2 BRANCH, KARACHI Iqbal, Main University Road, Karachi ALLAMA IQBAL ROAD 684-C, Main Allama Iqbal Road, P.E.C.H.S., 8 0053 KARACHI Sindh 021-34387673-4 BRANCH, KARACHI Off: Tariq Road, Karachi Shop Nos: 14, 15 & 16, Billy's Paradise, Block- GULISTAN-E-JAUHAR 9 0040 KARACHI Sindh 18, KDA Scehme No: 36, Gulistan-e-Jauhar, 021-34020944-5 BRANCH, KARACHI Karachi Shop No: 2, Plot No: 30, Qazi Court, Kararchi BAHADURABAD BRANCH, 10 0066 KARACHI Sindh Co-operative Housing Societies Unions Area, 021-34135842-3 KARACHI Bahadurabad, Karachi Plot No: SR-2/11/2/1, Office No: 105-108, Al- 11 0002 MAIN BRANCH KARACHI KARACHI Sindh 021-32436990-4 Rahim Tower, I.I.