The Genre Structure of Bulletin Board Messages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Technology: Applications DLIS408

Information Technology: Applications DLIS408 Edited by: Jovita Kaur INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY: APPLICATIONS Edited By Jovita Kaur Printed by LAXMI PUBLICATIONS (P) LTD. 113, Golden House, Daryaganj, New Delhi-110002 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara DLP-7765-079-INFO TECHNOLOGY APPLICATION C-4713/012/02 Typeset at: Shubham Composers, Delhi Printed at: Sanjay Printers & Publishers, Delhi SYLLABUS Information Technology: Applications Objectives: • To understand the applications of Information technology in organizations. • To appreciate how information technology can help to improve decision-making in organizations. • To appreciate how information technology is used to integrate the business disciplines. • To introduce students to business cases, so they learn to solve business problems with information technology. • To introduce students to the strategic applications of information technology. • To introduce students to the issues and problems involved in building complex systems and organizing information resources. • To introduce students to the social implications of information technology. • To introduce students to the management of information systems. S. No. Topics Library automation: Planning and implementation, Automation of housekeeping operations – Acquisition, 1. Cataloguing, Circulation, Serials control OPAC Library management. 2. Library software packages: RFID, LIBSYS, SOUL, WINISIS. 3. Databases: Types and generations, salient features of select bibliographic databases. 4. Communication technology: Fundamentals communication media and components. 5. Network media and types: LAN, MAN, WAN, Intranet. 6. Digital, Virtual and Hybrid libraries: Definition and scope. Recent development. 7. Library and Information Networks with special reference to India: DELNET, INFLIBNET, ERNET, NICNET. Internet—based resources and services Browsers, search engines, portals, gateways, electronic journals, mailing 8. list and scholarly discussion lists, bulletin board, computer conference and virtual seminars. -

The Kermit File Transfer Protocol

THE KERMIT FILE TRANSFER PROTOCOL Frank da Cruz February 1985 This is the original manuscript of the Digital Press book Kermit, A File Transfer Protocol, ISBN 0-932976-88-6, Copyright 1987, written in 1985 and in print from 1986 until 2001. This PDF file was produced by running the original Scribe markup-language source files through the Scribe publishing package, which still existed on an old Sun Solaris computer that was about to be shut off at the end of February 2016, and then converting the resulting PostScript version to PDF. Neither PostScript nor PDF existed in 1985, so this result is a near miracle, especially since the last time this book was "scribed" was on a DECSYSTEM-20 for a Xerox 9700 laser printer (one of the first). Some of the tables are messed up, some of the source code comes out in the wrong font; there's not much I can do about that. Also (unavoidably) the page numbering is different from the printed book and of couse the artwork is missing. Bear in mind Kermit protocol and software have seen over 30 years of progress and development since this book was written. All information herein regarding the Kermit Project, how to get Kermit software, or its license or status, etc, is no longer valid. The Kermit Project at Columbia University survived until 2011 but now it's gone and all Kermit software was converted to Open Source at that time. For current information, please visit the New Open Source Kermit Project website at http://www.kermitproject.org (as long as it lasts). -

Electronic Bulletin Boards for Business, Education and Leisure

Visions in Leisure and Business Volume 6 Number 1 Article 6 1987 Electronic Bulletin Boards for Business, Education and Leisure Kent L. Gustafson University of Georgia Charles Connor University of Georgia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions Recommended Citation Gustafson, Kent L. and Connor, Charles (1987) "Electronic Bulletin Boards for Business, Education and Leisure," Visions in Leisure and Business: Vol. 6 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions/vol6/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visions in Leisure and Business by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ELECTRONIC BULLETIN BOARDS FOR BUSINESS, EDUCATION AND LEISURE BY DR. KENT L. GUSTAFSON, PROFESSOR AND CHARLES CONNOR, RESEARCH ASSOCIATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL MEDIA AND TECHNOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA ATHENS, GEORGIA 30602 ABSTRACT Electronic communication is one example of how technology is impacting and changing lifestyles. The result of this technology is one of benefiting the individual, especially since the cost of this technology is within the reach of most families. ELECTRONIC BULLETIN BOARDS FOR BUSINESS, EDUCATION AND LEISURE INTRODUCTION Using computers to communicate with other people and to forward and store messages has been possible for many years. But until recently, this capability was available to only a limited number of people due to expense and technical difficulty. However, with the advent and rapid acquisition of personal computers, the ability to communicate electronically has become readily available in offices and homes. Personal computers have made the costs of electronic communication inexpensive due to the low costs of both the host computer and personal computers used to communicate with it� Microcomputers costing less than $1,000 can serve as the host computer and home computers with required communication equipment and programs can be purchased for under $500. -

Reports - Descriptive (141)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 270 039 IR 012 107 AUTHOR Spurgin, Judy Barrett TITLE Educator's Guide to Networking: Using Computers. INSTITUTION Southwest Educational Development Lab., Austin, Tex. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 66p. AVAILABLE FROMSouthwest Educational DevelJpment Laboratory, 211 East Seventh Street, Austin, TX 78701. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroo Use (055) -- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administrators; *Communications; *Computer Networks; Databases; *Information Networks; *Information Systems; *Microcomputers; Position Papers; students; Teachers; *Telecommunications ABSTRACT Since electronic networking via microcomputers is fast becoming one of the most popular communications mediums of this decade, this manual is designed to help educators use personal computers as communication devices. Tha purpose of the document is to acquaint the reader with: (1) the many available communications options on electronic networks; (2) how-to activities that will, with some practice and experience, make one a "networking expert"; and (3) resources and services related to electronic networking. Presuming n technological sophistication since none is required, it presentsa step-by-step description of computer networking and the ways it is being used by educators and students throughout the country. Suggestions for ways to ease into comput..r networking are also provided, along with some examples of how a typical networking session might proceed. The manual does not detail hardware and software requirements, nor does -

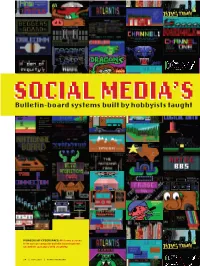

Bulletin-Board Systems Built by Hobbyists Taught People How to Interact Online • by Kevin Driscoll

SOCIALSOCIAL MEMEDDIA’IA’SS Bulletin-board systems built by hobbyists taught people how to interact online • By KEVIN DRISCOLL OES HERE OES G PIONEERS OF CYBERSPACE: Welcome screens from various computer bulletin-board systems show their operators’ wild creativity. GUTTER CREDIT CREDIT GUTTER 54 | NOV 2016 | NORTH AMERICAN 11.ComputerBBSes.INT - 11.ComputerBBBes.NA [P]{NA}.indd 54 10/13/16 4:22 PM DDIAL-UPIAL-UP ROOTROOTSS Bulletin-board systems built by hobbyists taught people how to interact online • By KEVIN DRISCOLL SPECTRUM.IEEE.ORG | NORTH AMERICAN | NOV 2016 | 55 11.ComputerBBSes.INT - 11.ComputerBBBes.NA [P]{NA}.indd 55 10/13/16 4:22 PM be paved over in the construction of today’s information For millions of people superhighway. So it takes some digging to reveal what around the globe, came before. the Internet is a simple fact of life. We How did it all start? During the snowy winter of take for granted the invisible network 1978, Ward Christensen and Randy Suess, members of the that enables us to communicate, navigate, Chicago Area Computer Hobbyist’s Exchange (CACHE), began investigate, flirt, shop, and play. Early on, to assemble what would become the best known of the first small-scale BBSs. Members of CACHE were passionate about this network-of- networks connected only microcomputers, at the time an arcane endeavor, and so the select companies and university campuses. club’s newsletters were an invaluable source of information. Nowadays, it follows almost all of us into Christensen and Suess’s novel idea was to put together an the most intimate areas of our lives. -

The Hacker Crackdown

LITERARY FREEWARE — Not for Commercial Use by Bruce Sterling <[email protected]> Sideways PDF version 0.1 by E-Scribe <[email protected]> C O N T E N T S Preface to the Electronic Release of The Hacker Crackdown Chronology of the Hacker Crackdown Introduction Part 1: CRASHING THE SYSTEM A Brief History of Telephony / Bell's Golden Vaporware / Universal Service / Wild Boys and Wire Women / The Electronic Communities / The Ungentle Giant / The Breakup / In Defense of the System / The Crash Post- Mortem / Landslides in Cyberspace Part 2: THE DIGITAL UNDERGROUND Steal This Phone / Phreaking and Hacking / The View From Under the Floorboards / Boards: Core of the Underground / Phile Phun / The Rake's Progress / Strongholds of the Elite / Sting Boards / Hot Potatoes / War on the Legion / Terminus / Phile 9-1-1 / War Games / Real Cyberpunk Part 3: LAW AND ORDER Crooked Boards / The World's Biggest Hacker Bust / Teach Them a Lesson / The U.S. Secret Service / The Secret Service Battles the Boodlers / A Walk Downtown / FCIC: The Cutting-Edge Mess / Cyberspace Rangers / FLETC: Training the Hacker-Trackers Part 4: THE CIVIL LIBERTARIANS NuPrometheus + FBI = Grateful Dead / Whole Earth + Computer Revolution = WELL / Phiber Runs Underground and Acid Spikes the Well / The Trial of Knight Lightning / Shadowhawk Plummets to Earth / Kyrie in the Confessional / $79,499 / A Scholar Investigates / Computers, Freedom, and Privacy Electronic Afterwordto *The Hacker Crackdown,* New Years' Day 1994 BRUCE STERLING — THE HACKER CRACKDOWN NOT FOR COMMERCIAL USE 2 Preface to the Electronic Release of The Hacker Crackdown January 1, 1994 — Austin, Texas Hi, I'm Bruce Sterling, the author of this electronic book. -

The ZMODEM Inter Application File Transfer Protocol Chuck Forsberg

The ZMODEM Inter Application File Transfer Protocol Chuck Forsberg Omen Technology Inc A overview of this document is available as ZMODEM.OV (in ZMDMOV.ARC) Omen Technology Incorporated The High Reliability Software 17505-V Northwest Sauvie Island Road Portland Oregon 97231 VOICE: 503-621-3406 :VOICE Modem: 503-621-3746 Speed 1200,2400,19200 Compuserve:70007,2304 GEnie:CAF UUCP: ...!tektronix!reed!omen!caf Chapter 0 Rev 8-3-87 Typeset 8-4-87 1 Page: 1 Chapter 0 ZMODEM Protocol 2 1. INTENDED AUDIENCE This document is intended for telecommunications managers, systems programmers, and others who choose and implement asynchronous file transfer protocols over dial-up networks and related environments. 2. WHY DEVELOP ZMODEM? Since its development half a decade ago, the Ward Christensen MODEM protocol has enabled a wide variety of computer systems to interchange data. There is hardly a communications program that doesn't at least claim to support this protocol, now called XMODEM. Advances in computing, modems and networking have spread the XMODEM protocol far beyond the micro to micro environment for which it was designed. These application have exposed some weaknesses: + The awkward user interface is suitable for computer hobbyists. Multiple commands must be keyboarded to transfer each file. + Since commands must be given to both programs, simple menu selections are not possible. + The short block length causes throughput to suffer when used with timesharing systems, packet switched networks, satellite circuits, and buffered (error correcting) modems. + The 8 bit checksum and unprotected supervison allow undetected errors and disrupted file transfers. + Only one file can be sent per command. -

Post-Modemism: the Role of User Adoption of Teletext, Videotex & Bulletin Board Systems in the History of the Internet

POST-MODEMISM: THE ROLE OF USER ADOPTION OF TELETEXT, VIDEOTEX & BULLETIN BOARD SYSTEMS IN THE HISTORY OF THE INTERNET by Jay Kelly McKinnon B.A. University of British Columbia, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology Ó Jay Kelly McKinnon 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Jay Kelly McKinnon Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Post-modemism: the role of user adoption of teletext, videotex & bulletin board systems in the history of the Internet Examining Committee: Chair: Roman Onufrijchuk, Senior Lecturer Richard Smith Senior Supervisor Professor Peter Anderson Supervisor Associate Professor Adam Holbrook External Examiner Associate Director, Center for Policy Research on Science and Technology, Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: March 29, 2012 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract The enduring policy conflicts of the Information Age increasingly demand a history of technology that acknowledges the legacy of accumulated user experience across successive paradigms and generations of communication media. Interrogation of the histories of Internet, teletext, videotex and bulletin board system (BBS) technologies, reveal the 1980s as a watershed decade for the radically decentralized socialization of digital communication. While each new technical paradigm requires cultural practices to socialize the products of engineering, the prevalence of elite- and infrastructure-focused histories reflect a systematic preference for describing centralized processes of engineering. -

A Comparison Between the Early Days of the Public Internet and the Darknet Freenet

A comparison between the early days of the public Internet and the darknet Freenet First draft 14/03/2011 Megan Hoogenboom Elements: The early days of the public Internet The commercialisation of the public Internet The beginning of Freenet The structure of Freenet Comparison between early public Internet and the Freenet Darknet (conclusion) Future of darknet's like Freenet (This first draft of my final thesis has also elements implemented I want to add at a later stadium, to make the parts that are already wrote more clear.) 1 The early days of the public Internet As a result of the adoption of Part 68 of Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations by the FCC in 1977, all costumers of a telephone and telephone line could finally attach any devise they wished to the network. Before this was held back by AT&T, which was the monopoly of telephones at that time, because of commercial benefits. The network could now be opened for earlier developed networking systems, opened up by ARPANET created by ARPA, The Advanced Research Projects Agency, which was part of the Department of Defence of the US (Griffiths 2002, http://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/history/ivh/chap2.htm). In 1978 Ward Christensen and Randy Suess developed a new piece of software; the Computer Bulletin Board System, BBS (Gilbertson 2010, http://www.wired.com/thisdayintech/tag/ward-christensen/). This small program was only available if one person received a phone call, and would shut down if the caller hung up. While they were connected the one who made the call could send commands to the computer on the other end of the line. -

Bulletin Board System for Libraries

DESIDOC Bulletin of IAformation Technology, Vol. 15, No. 4, July 1995, pp, 23-31 0 1995, DESIDOC Bulletin Board System for Libraries CK Ramaiah DESIDOC, Metcalfe House, Delhi- 1 10 054 Abstract Electronic bulletin board systems are vital tools for computer-mediated communication among computer users. These are similar to the bulletin boards that are displayed in a library. However, these are operated electronically on computer networks. This article gives an overview about electronic BBSs, the infrastructure required to set up BBS, and their applications in general. An attempt has also been made to design an Indian Bulletin Board System for tibraries, a conceptual BBS on which different types of information could be organised and a number of services could be provided to the users. 1. INTRODUCTION 2. WHAT IS A BBS? Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) started in The BBS is a miniature form of an online the late 70s, as a means of communication system for a cost-effective distribution of for virtual community existing in information in electronic format. BBS Cyberspace where participants usually supports interactive communication under pseudonames may send and receive between users on a wide variety of public and private messages to each other subjects ranging from hobbies to politics. on any topic, transfer software, play online On some BBSs, it is possible for the users to games, etc. Ward Christensen and Randy communicate both interactively and to Suess of USA had discussed on 18 January leave messages for other users. Some 1978, about designing of the first bulletin boards are considered more of a electronic BBS in the world and talk-net than a platform to exchange implemented the system on 16 February research information. -

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier

The Virtual Community Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier by Howard Rheingold ADDISON-WESLEY PUBLISHING COMPANY Reading, MA Copyright © 1993 by Howard Rheingold "When you think of a title for a book, you are forced to think of something short and evocative, like, well, 'The Virtual Community,' even though a more accurate title might be: 'People who use computers to communicate, form friendships that sometimes form the basis of communities, but you have to be careful to not mistake the tool for the task and think that just writing words on a screen is the same thing as real community.'" – HLR We know the rules of community; we know the healing effect of community in terms of individual lives. If we could somehow find a way across the bridge of our knowledge, would not these same rules have a healing effect upon our world? We human beings have often been referred to as social animals. But we are not yet community creatures. We are impelled to relate with each other for our survival. But we do not yet relate with the inclusivity, realism, self-awareness, vulnerability, commitment, openness, freedom, equality, and love of genuine community. It is clearly no longer enough to be simply social animals, babbling together at cocktail parties and brawling with each other in business and over boundaries. It is our task--our essential, central, crucial task--to transform ourselves from mere social creatures into community creatures. It is the only way that human evolution will be able to proceed. M. Scott Peck The Different Drum: Community-Making -

IQP DMO 3323 the ORAL HISTORY of VIDEO GAMES Interactive

IQP DMO 3323 THE ORAL HISTORY OF VIDEO GAMES Interactive Qualifying Project Report Completed in Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelor of Science Degree at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA Submitted to: Professor Dean M. O’Donnell (adviser) Suzanne DelPrete Eyleen Graedler March 5, 2013 This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. 1 Abstract: We interviewed Andrew “Zarf” Plotkin and Stuart Galley to further expand the IGDA Game Preservation SIG1 and Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s Oral History of Video Games website2. Prior to the interviews with Plotkin and Galley, we conducted practice interviews on WPI students to ascertain the best way to conduct an interview. We also viewed documentaries to examine different ways in which professionals conducted good interviews and edited them to correctly to capture their essence. 1 IGDA preservation website <http://www.igda.org/preservation> 2 Oral History of Video Games Website <http://alpheus.wpi.edu/imgd/oral-history/> 2 Authorship Page: Suzanne DelPrete and Eyleen Graedler each had individual as well as group responsibilities in the completion of the IQP. As a group, we watched various documentaries to get a feel for how interviews are conducted. While researching subjects to interview, Suzanne wrote up the biography for Andrew Plotkin while Eyleen wrote up one for Stuart Galley. Suzanne DelPrete was the video editor and outreach person of this IQP. She contacted possible interviewees and worked with them to set up interview times and locations.