Human Rights and Democracy in Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Government of Albay and the Center for Initiatives And

Strengthening Climate Resilience Provincial Government of Albay and the SCR Center for Initiatives and Research on Climate Adaptation Case Study Summary PHILIPPINES Which of the three pillars does this project or policy intervention best illustrate? Tackling Exposure to Changing Hazards and Disaster Impacts Enhancing Adaptive Capacity Addressing Poverty, Vulnerabil- ity and their Causes In 2008, the Province of Albay in the Philippines was declared a "Global Local Government Unit (LGU) model for Climate Change Adapta- tion" by the UN-ISDR and the World Bank. The province has boldly initiated many innovative approaches to tackling disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation (CCA) in Albay and continues to integrate CCA into its current DRM structure. Albay maintains its position as the first mover in terms of climate smart DRR by imple- menting good practices to ensure zero casualty during calamities, which is why the province is now being recognized throughout the world as a local govern- ment exemplar in Climate Change Adap- tation. It has pioneered in mainstreaming “Think Global Warming. Act Local Adaptation.” CCA in the education sector by devel- oping a curriculum to teach CCA from -- Provincial Government of Albay the primary level up which will be imple- Through the leadership of Gov. Joey S. Salceda, Albay province has become the first province to mented in schools beginning the 2010 proclaim climate change adaptation as a governing policy, and the Provincial Government of Albay schoolyear. Countless information, edu- cation and communication activities have (PGA) was unanimously proclaimed as the first and pioneering prototype for local Climate Change been organized to create climate change Adaptation. -

Amir, Abbas Review Palestinian Situation

QATAR | Page 4 SPORT | Page 1 Dreama Former F1 holds champion forum Niki Lauda for foster dies at 70 families published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXX No. 11191 May 22, 2019 Ramadan 17, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir, Abbas review Palestinian situation His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met with the Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas at the Amiri Diwan yesterday. During the meeting, they discussed the situation in Palestine, where Abbas briefed the Amir on the latest developments, and expressed sincere thanks to His Highness the Amir for Qatar’s steadfast support for the Palestinian cause and for its standing with the Palestinian people in facing the diff icult circumstances and challenges. The meeting was attended by a number of ministers and members of the off icial delegation accompanying the Palestinian president. His Highness the Amir hosted an Iftar banquet in honour of the Palestinian president and the delegation accompanying him at the Amiri Diwan. The banquet was attended by a number of ministers. In brief QATAR | Reaction Accreditation programme Qatar condemns armed New Trauma & Emergency attack in northeast India launched for cybersecurity Qatar has strongly condemned the armed attack which targeted Centre opens partially today audit service providers a convoy of vehicles in the state of Arunachal Pradesh in northeast QNA before being discharged. QNA Abdullah, stressed on the importance India, killing many people including Doha The new facility, which is located on Doha of working within the framework of the a local MP and injuring others. -

'Sin' Tax Bill up for Crucial Vote

Headline ‘Sin’ tax bill up for crucial vote MediaTitle Manila Standard Philippines (www.thestandard.com.ph) Date 03 Jun 2019 Section NEWS Order Rank 6 Language English Journalist N/A Frequency Daily ‘Sin’ tax bill up for crucial vote Advocates of a law raising taxes on cigarettes worried that heavy lobbying by tobacco companies over the weekend could affect the vote in the Senate Monday. Former Philhealth director Anthony Leachon and UP College of Medicine faculty member Antonio Dans said a failure of the bill to pass muster would deprive the government’s Universal Health Care program of funding. “Definitely, the lobbying can affect how our senators will behave... how they will vote,” said Leachon, also chairman of the Council of Past Presidents of the Philippine College of Physicians. But Leachon and Dans said they remained confident that senators who supported the sin tax law in 2012 would support the new round of increases on cigarette taxes. These were Senate Minority Leader Franklin Drilon, Senators Panfilo Lacson, Francis Pangilinan, Antonio Trillanes IV and re-elected Senator Aquilino Pimentel III. They are also hopeful that the incumbent senators who voted against the increase in the excise taxes on cigarettes in 2012—Senate President Vicente Sotto III, Senate Pro Tempore Ralph Rectp and outgoing Senators Francis Escudero and Gregorio Honasan—would have a change of heart. While Pimentel, who ran in the last midterm elections, supported the increase in tobacco taxes in 2012, he did not sign Senator Juan Edgardo Angara’s committee report, saying the bill should be properly scrutinized as it might result in the death of the tobacco industry. -

Duterte and Philippine Populism

JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ASIA, 2017 VOL. 47, NO. 1, 142–153 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751 COMMENTARY Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism Nicole Curato Centre for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance, University of Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This commentary aims to take stock of the 2016 presidential Published online elections in the Philippines that led to the landslide victory of 18 October 2016 ’ the controversial Rodrigo Duterte. It argues that part of Duterte s KEYWORDS ff electoral success is hinged on his e ective deployment of the Populism; Philippines; populist style. Although populism is not new to the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte; elections; Duterte exhibits features of contemporary populism that are befit- democracy ting of an age of communicative abundance. This commentary contrasts Duterte’s political style with other presidential conten- ders, characterises his relationship with the electorate and con- cludes by mapping populism’s democratic and anti-democratic tendencies, which may define the quality of democratic practice in the Philippines in the next six years. The first six months of 2016 were critical moments for Philippine democracy. In February, the nation commemorated the 30th anniversary of the People Power Revolution – a series of peaceful mass demonstrations that ousted the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III – the son of the president who replaced the dictator – led the commemoration. He asked Filipinos to remember the atrocities of the authoritarian regime and the gains of democracy restored by his mother. He reminded the country of the torture, murder and disappearance of scores of activists whose families still await compensation from the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board. -

18 DECEMBER 2020, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC December 18, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article

18 DECEMBER 2020, FRIDAY Headline STRATEGIC December 18, 2020 COMMUNICATION & Editorial Date INITIATIVES Column SERVICE 1 of 2 Opinion Page Feature Article Cimatu wants augmentation teams in fight vs. illegal logging Published December 17, 2020, 1:02 PM by Ellalyn De Vera-Ruiz Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Secretary Roy Cimatu has ordered the creation of augmentation teams to ensure that no illegal logging activities are being conducted in Cagayan Valley, Bicol region, and the Upper Marikina River Basin Protected Landscape. Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu (NTF AGAINST COVID-19 / MANILA BULLETIN) Cimatu directed DENR Undersecretary for Special Concerns Edilberto Leonardo to create four special composite teams that would augment the anti-illegal logging operations in those areas. He said the creation of augmentation teams is a strategic move on the part of the DENR to shift its orientation in forest protection operation more towards prevention by “going hard and swift” against the financiers and operators. The order is pursuant to Executive Order 23, Series of 2011, which calls for the creation of anti-illegal logging task force from the national to the regional and provincial levels. Each team is composed of representatives from the DENR, Department of the Interior and Local Government, Department of National Defense, Armed Forces of the Philippines, and Philippine National Police. Cimatu said the key to curbing illegal logging is to identify and penalize the financiers and operators, noting that only transporters and buyers in possession of undocumented forest products are oftentimes collared in illegal logging operations. The DENR chief has recognized the agency’s need to shift from reactive to proactive efforts to absolutely curtail illegal logging activities in the country. -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

Southern Philippines, February 2011

Confirms CORI country of origin research and information CORI Country Report Southern Philippines, February 2011 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made by nationals from the southern Philippines, specifically Mindanao, Tawi Tawi, Basilan and Sulu. This report covers events up to 28 February 2011. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

Philippines and Elsewhere May 20, 2011

INVESTMENT CLIMATE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT NEWSCLIPS Economic Reform News from the Philippines and Elsewhere May 20, 2011 Philippines Competitiveness goal set Business World, May 16, 2011 Emerging markets soon to outstrip rich ones, Eliza J. Diaz says WB Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 COMPETITIVENESS planners have set an Michelle V. Remo ambitious goal of boosting the Philippines’ global ranking in the next five years, highlighting Emerging economies like the Philippines will the need for sustained government interventions play an increasingly important role in the global if the country is to rise up from its perennial economy over the medium to long term, bottom half showings. continually exceeding growth rates of industrialized nations and accounting for bigger shares of the world’s output. Train line to connect Naia 3, Fort, Makati Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 Paolo G. Montecillo Gov’t to ask flight schools to move out of Naia Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 A new commuter train line may soon connect the Paolo G. Montecillo Ninoy Aquino International Airport (Naia) terminal 3 to the Fort Bonifacio and Makati The government has given flight schools six central business districts, according to the Bases months to submit detailed plans to move out of Conversion and Development Authority Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport (BCDA). (Naia) to reduce delays caused by congestion at the country’s premier gateway. Mitsubishi seeks extension of railway bid Business Mirror, May 17, 2011 LTFRB gets tough on bus firms resisting gov’t Lenie Lectura inventory Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 MITSUBISHI Corp., one of the 15 companies Paolo G. -

A Popular Strongman Gains More Power by Joseph Purugganan September 2019

Blickwechsel Gesellscha Umwelt Menschenrechte Armut Politik Entwicklung Demokratie Gerechtigkeit In the Aftermath of the 2019 Philippine Elections: A Popular Strongman Gains More Power By Joseph Purugganan September 2019 The Philippines concluded a high-stakes midterm elections in May 2019, that many consider a critical turning point in our nation’s history. While the Presidency was not on the line, and Rodrigo Duterte himself was not on the ballot, the polls were seen as a referendum on his presidency. Duterte has drawn flak for his deadly ‘War on In midterm elections, voters have historically fa- Drugs’ that has taken the lives of over 5,000 vored candidates backed by a popular incumbent suspects according to official police accounts, and rejected those supported by unpopular ones. but the death toll could be as high as 27,000 ac- In the 2013 midterms for instance, the adminis- cording to the Philippine Commission on Human tration supported by former President Benigno Rights. The administration has also been criti- Aquino III, won 9 out of 12 Senate seats. Like cized for its handling of the maritime conflict Duterte, Aquino had a high satisfaction rating with China in the West Philippine Sea. heading into the midterms. In contrast, a very unpopular Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, with neg- Going into the polls however, Duterte, despite ative net satisfaction ratings, weighed down the all the criticisms at home and abroad, has main- administration ticket. In the Senate race in 2007, tained consistently high popularity and trust the Genuine Opposition coalition was able to se- ratings. The latest survey conducted five months cure eight out of 12 Senate seats, while Arroyo’s ahead of the elections showed the President Team Unity only got two seats and the other two having a 76 percent trust score and an 81 percent slots went to independent candidates. -

Philippine Political Economy 1998-2018: a Critical Analysis

American Journal of Research www.journalofresearch.us ¹ 11-12, November-December 2018 [email protected] SOCIAL SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES Manuscript info: Received November 4, 2018., Accepted November 12, 2018., Published November 30, 2018. PHILIPPINE POLITICAL ECONOMY 1998-2018: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS Ruben O Balotol Jr, [email protected] Visayas State University-Baybay http://dx.doi.org/10.26739/2573-5616-2018-12-2 Abstract: In every decision than an individual deliberates always entails economic underpinnings and collective political decisions to consider that affects the kind of decision an individual shape. For example governments play a major role in establishing tax rates, social, economic and environmental goals. The impact of economic and politics are not only limited from one's government, different perspectives and region of the globe are now closely linked imposing ideology and happily toppling down cultural threat to their interests. According to Žižek (2008) violence is not solely something that enforces harm or to an individual or community by a clear subject that is responsible for the violence. Violence comes also in what he considered as objective violence, without a clear agent responsible for the violence. Objective violence is caused by the smooth functioning of our economic and political systems. It is invisible and inherent to what is considered as normal state of things. Objective violence is considered as the background for the explosion of the subjective violence. It fore into the scene of perceptibility as a result of multifaceted struggle. It is evident that economic growth was as much a consequence of political organization as of conditions in the economy. -

Resume of Chairman Gregorio D. Garcia

GREGORIO D. GARCIA III Hello. PROFILE Greg is a marketing and branding/communications professional with a strong exposure in banking and real estate development. Today, Greg is a leading political consultant and is associated with the political campaigns of Senators Panfilo Lacson, Pia Cayetano, Alan Cayetano, Juan Edgardo Angara, Joel Villanueva, Nancy Binay, the vice presidential run of Jejomar Binay and the presidential campaign of Rodrigo Duterte. He was also involved in the mayoral campaigns of Lani Cayetano in Taguig and John Ray Tiangco in Navotas. Greg was also involved as consultant in the development of new marketing services under development by PagIbig, working with its CEO, Atty. Darlene Berberabe. He has a continuing involvement in the communications narrative of St. Luke’s Hospital and Nickel Asia Corporation. Greg finished all his schooling in Colegio De San Juan De Letran and finished in 1960. He is married to Myrna Nuyda of Camalig, Albay and has three daughters who are all in the fields of arts and culture. Greg was born on 28 June 1943. EXPERIENCE CREATIVE HEAD, ACE COMPTON ADVERTISING 1964-67 63917- 5 2 5 7 6 5 6 TWO SALCEDO PLACE CONDOMINIUM,TORDESIL LAS ST. PHONE ADDRESS Greg started as a copywriter and then became the lead creative for the Procter and Gamble business handling Tide and Safeguard. VICE-PRESIDENT, MARKETING 1967-1977 His well-earned marketing and branding reputation is associated with the success of Banco Filipino in the 60s and the 70s when he was pirated from Ace-Compton by Tomas B. Aguirre to help propel Banco Filipino as the biggest savings bank during that period. -

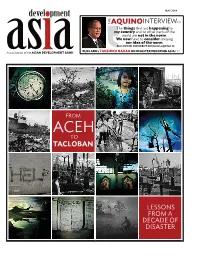

From Aceh to Tacloban: Lessons from A

MAY 2014 P.18 THE AQUINOINTERVIEW The things that are happening to my country and to other parts of the world are not in the norm. We now have to consider revising our idea of the norm. PHILIPPINES PRESIDENT BENIGNO AQUINO III A publication of the ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK PLUS ADB’s TAKEHIKO NAKAO ON DISASTER PROOFING ASIA P.34 FROM ACEH TO TACLOBAN LESSONS FROM A DECADE OF DISASTER Work for Asia and the Pacifi c. Work for ADB. The only development bank dedicated to Asia and the Pacifi c is hiring people dedicated to development. ADB seeks highly qualifi ed individuals for the following vacancies: ƷɆ*!.#5ɆƷɆ%**%(Ɇ*#!)!*0ɆƷɆ%**%(Ɇ!0+.ɆƷɆ.%20!Ɇ!0+.Ɇ%**!Ɇ ƷɆ"!#1. /ɆƷɆ.*/,+.0ɆƷɆ0!.Ɇ1,,(5Ɇ* Ɇ*%00%+* +)!*Ɇ.!Ɇ!*+1.#! Ɇ0+Ɇ,,(5Ɓ +.Ɇ)+.!Ɇ !0%(/ƂɆ2%/%0Ɇ333Ɓ Ɓ+.#Ɲ.!!./ ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Inside MAY 2014 P.18 SPECIAL REPORT THE AQUINOINTERVIEW The things that are happening to my country and to other parts of the world are not in the norm. We now have to consider revising our idea of the norm. PHILIPPINES PRESIDENT BENIGNO AQUINO III PLUS ADB’s TAKEHIKO NAKAO ON DISASTER PROOFING ASIA P.32 A publication of the ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK From Aceh to Tacloban 31 Aid Watch A rising tide of disasters has 8 What have we learned from a spurred a sharper focus on FROM decade of disaster? how aid is used ACEH TO TACLOBAN 17 Taking Cover 34 Opinion: Asia needs more protection against Takehiko Nakao the financial cost of disaster ADB President LESSONS says disaster FROM A DECADE OF DISASTER Cover Photos : Gerhard Joren (Tacloban; color); Veejay Villafranca risk will check (Tacloban; black and white); Getty Images (Aquino) Asia’s growth 32 We cannot allow the cycle of destruction and reconstruction to continue by rebuilding communities in the exact same manner.