MAF1 Represses CDKN1A Through a Pol III-Dependent Mechanism Yu-Ling Lee, Yuan-Ching Li, Chia-Hsin Su, Chun-Hui Chiao, I-Hsuan Lin, Ming-Ta Hsu*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-Like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2006 Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene Yutao Liu University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Yutao, "Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino- like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1824 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Yutao Liu entitled "Molecular and Physiological Basis for Hair Loss in Near Naked Hairless and Oak Ridge Rhino-like Mouse Models: Tracking the Role of the Hairless Gene." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Life Sciences. Brynn H. Voy, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Naima Moustaid-Moussa, Yisong Wang, Rogert Hettich Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

A Network Propagation Approach to Prioritize Long Tail Genes in Cancer

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.05.429983; this version posted February 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. A Network Propagation Approach to Prioritize Long Tail Genes in Cancer Hussein Mohsen1,*, Vignesh Gunasekharan2, Tao Qing2, Sahand Negahban3, Zoltan Szallasi4, Lajos Pusztai2,*, Mark B. Gerstein1,5,6,3,* 1 Computational Biology & Bioinformatics Program, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA 2 Breast Medical Oncology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06511, USA 3 Department of Statistics & Data Science, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA 4 Children’s Hospital Informatics Program, Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA 5 Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA 6 Department of Computer Science, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA * Corresponding author Abstract Introduction. The diversity of genomic alterations in cancer pose challenges to fully understanding the etiologies of the disease. Recent interest in infrequent mutations, in genes that reside in the “long tail” of the mutational distribution, uncovered new genes with significant implication in cancer development. The study of these genes often requires integrative approaches with multiple types of biological data. Network propagation methods have demonstrated high efficacy in uncovering genomic patterns underlying cancer using biological interaction networks. Yet, the majority of these analyses have focused their assessment on detecting known cancer genes or identifying altered subnetworks. -

Molecular Structure of Promoter-Bound Yeast TFIID

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07096-y OPEN Molecular structure of promoter-bound yeast TFIID Olga Kolesnikova 1,2,3,4, Adam Ben-Shem1,2,3,4, Jie Luo5, Jeff Ranish 5, Patrick Schultz 1,2,3,4 & Gabor Papai 1,2,3,4 Transcription preinitiation complex assembly on the promoters of protein encoding genes is nucleated in vivo by TFIID composed of the TATA-box Binding Protein (TBP) and 13 TBP- associate factors (Tafs) providing regulatory and chromatin binding functions. Here we present the cryo-electron microscopy structure of promoter-bound yeast TFIID at a resolu- 1234567890():,; tion better than 5 Å, except for a flexible domain. We position the crystal structures of several subunits and, in combination with cross-linking studies, describe the quaternary organization of TFIID. The compact tri lobed architecture is stabilized by a topologically closed Taf5-Taf6 tetramer. We confirm the unique subunit stoichiometry prevailing in TFIID and uncover a hexameric arrangement of Tafs containing a histone fold domain in the Twin lobe. 1 Department of Integrated Structural Biology, Equipe labellisée Ligue Contre le Cancer, Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Illkirch 67404, France. 2 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UMR7104, 67404 Illkirch, France. 3 Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U1258, 67404 Illkirch, France. 4 Université de Strasbourg, Illkirch 67404, France. 5 Institute for Systems Biology, Seattle, WA 98109, USA. These authors contributed equally: Olga Kolesnikova, Adam Ben-Shem. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to P.S. (email: [email protected]) or to G.P. -

SLFN11 Promotes CDT1 Degradation by CUL4 in Response to Replicative DNA Damage, While Its Absence Leads to Synthetic Lethality with ATR/CHK1 Inhibitors

SLFN11 promotes CDT1 degradation by CUL4 in response to replicative DNA damage, while its absence leads to synthetic lethality with ATR/CHK1 inhibitors Ukhyun Joa,1, Yasuhisa Muraia, Sirisha Chakkab, Lu Chenb, Ken Chengb, Junko Muraic, Liton Kumar Sahaa, Lisa M. Miller Jenkinsd, and Yves Pommiera,1 aDevelopmental Therapeutics Branch, Laboratory of Molecular Pharmacology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD 20814; bNational Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Functional Genomics Laboratory, NIH, Rockville, MD 20850; cInstitute for Advanced Biosciences, Keio University, 997-0052 Yamagata, Japan; and dLaboratory of Cell Biology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892 Edited by Richard D. Kolodner, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, La Jolla, CA, and approved December 8, 2020 (received for review July 29, 2020) Schlafen-11 (SLFN11) inactivation in ∼50% of cancer cells confers condensation related to deposition of H3K27me3 in the gene broad chemoresistance. To identify therapeutic targets and under- body of SLFN11 by EZH2, a histone methyltransferase (11). lying molecular mechanisms for overcoming chemoresistance, we Targeting epigenetic regulators is therefore an attractive com- performed an unbiased genome-wide RNAi screen in SLFN11-WT bination strategy to overcome chemoresistance of SLFN11- and -knockout (KO) cells. We found that inactivation of Ataxia deficient cancers (10, 25, 26). An alternative approach is to at- Telangiectasia- and Rad3-related (ATR), CHK1, BRCA2, and RPA1 tack SLFN11-negative cancer cells by targeting the essential SLFN11 overcome chemoresistance to camptothecin (CPT) in -KO pathways that cells use to overcome replicative damage and cells. Accordingly, we validate that clinical inhibitors of ATR replication stress. -

Molecular Mechanisms of Ribosomal Protein Gene Coregulation

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 3, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Molecular mechanisms of ribosomal protein gene coregulation Rohit Reja, Vinesh Vinayachandran, Sujana Ghosh, and B. Franklin Pugh Center for Eukaryotic Gene Regulation, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802, USA The 137 ribosomal protein genes (RPGs) of Saccharomyces provide a model for gene coregulation. We examined the positional and functional organization of their regulators (Rap1 [repressor activator protein 1], Fhl1, Ifh1, Sfp1, and Hmo1), the transcription machinery (TFIIB, TFIID, and RNA polymerase II), and chromatin at near-base-pair res- olution using ChIP-exo, as RPGs are coordinately reprogrammed. Where Hmo1 is enriched, Fhl1, Ifh1, Sfp1, and Hmo1 cross-linked broadly to promoter DNA in an RPG-specific manner and demarcated by general minor groove widening. Importantly, Hmo1 extended 20–50 base pairs (bp) downstream from Fhl1. Upon RPG repression, Fhl1 remained in place. Hmo1 dissociated, which was coupled to an upstream shift of the +1 nucleosome, as reflected by the Hmo1 extension and core promoter region. Fhl1 and Hmo1 may create two regulatable and positionally distinct barriers, against which chromatin remodelers position the +1 nucleosome into either an activating or a repressive state. Consistent with in vitro studies, we found that specific TFIID subunits, in addition to cross-linking at the core promoter, made precise cross-links at Rap1 sites, which we interpret to reflect native Rap1–TFIID interactions. Our findings suggest how sequence-specific DNA binding regulates nucleosome positioning and transcription complex assembly >300 bp away and how coregulation coevolved with coding sequences. -

Attachment PDF Icon

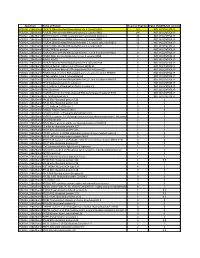

Spectrum Name of Protein Count of Peptides Ratio (POL2RA/IgG control) POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2A DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB1 197 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2B DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB2 146 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RPAP2 Isoform 1 of RNA polymerase II-associated protein 2 24 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2G DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB7 23 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2H DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC3 19 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2C DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB3 17 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2J RPB11a protein 7 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2E DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC1 8 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2I DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB9 9 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand ALMS1 ALMS1 3 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2D DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit RPB4 6 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand GRINL1A;Gcom1 Isoform 12 of Protein GRINL1A 6 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RECQL5 Isoform Beta of ATP-dependent DNA helicase Q5 3 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2L DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC5 5 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand KRT6A Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6A 3 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand POLR2K DNA-directed RNA polymerases I, II, and III subunit RPABC4 2 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RFC4 Replication factor C subunit 4 1 NOT IN CONTROL IP POLR2A_228kdBand RFC2 -

TAF10 Complex Provides Evidence for Nuclear Holo&Ndash;TFIID Assembly from Preform

ARTICLE Received 13 Aug 2014 | Accepted 2 Dec 2014 | Published 14 Jan 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7011 OPEN Cytoplasmic TAF2–TAF8–TAF10 complex provides evidence for nuclear holo–TFIID assembly from preformed submodules Simon Trowitzsch1,2, Cristina Viola1,2, Elisabeth Scheer3, Sascha Conic3, Virginie Chavant4, Marjorie Fournier3, Gabor Papai5, Ima-Obong Ebong6, Christiane Schaffitzel1,2, Juan Zou7, Matthias Haffke1,2, Juri Rappsilber7,8, Carol V. Robinson6, Patrick Schultz5, Laszlo Tora3 & Imre Berger1,2,9 General transcription factor TFIID is a cornerstone of RNA polymerase II transcription initiation in eukaryotic cells. How human TFIID—a megadalton-sized multiprotein complex composed of the TATA-binding protein (TBP) and 13 TBP-associated factors (TAFs)— assembles into a functional transcription factor is poorly understood. Here we describe a heterotrimeric TFIID subcomplex consisting of the TAF2, TAF8 and TAF10 proteins, which assembles in the cytoplasm. Using native mass spectrometry, we define the interactions between the TAFs and uncover a central role for TAF8 in nucleating the complex. X-ray crystallography reveals a non-canonical arrangement of the TAF8–TAF10 histone fold domains. TAF2 binds to multiple motifs within the TAF8 C-terminal region, and these interactions dictate TAF2 incorporation into a core–TFIID complex that exists in the nucleus. Our results provide evidence for a stepwise assembly pathway of nuclear holo–TFIID, regulated by nuclear import of preformed cytoplasmic submodules. 1 European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Grenoble Outstation, 6 rue Jules Horowitz, 38042 Grenoble, France. 2 Unit for Virus Host-Cell Interactions, University Grenoble Alpes-EMBL-CNRS, 6 rue Jules Horowitz, 38042 Grenoble, France. 3 Cellular Signaling and Nuclear Dynamics Program, Institut de Ge´ne´tique et de Biologie Mole´culaire et Cellulaire, UMR 7104, INSERM U964, 1 rue Laurent Fries, 67404 Illkirch, France. -

The Human Genome Project

TO KNOW OURSELVES ❖ THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY AND THE HUMAN GENOME PROJECT JULY 1996 TO KNOW OURSELVES ❖ THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY AND THE HUMAN GENOME PROJECT JULY 1996 Contents FOREWORD . 2 THE GENOME PROJECT—WHY THE DOE? . 4 A bold but logical step INTRODUCING THE HUMAN GENOME . 6 The recipe for life Some definitions . 6 A plan of action . 8 EXPLORING THE GENOMIC LANDSCAPE . 10 Mapping the terrain Two giant steps: Chromosomes 16 and 19 . 12 Getting down to details: Sequencing the genome . 16 Shotguns and transposons . 20 How good is good enough? . 26 Sidebar: Tools of the Trade . 17 Sidebar: The Mighty Mouse . 24 BEYOND BIOLOGY . 27 Instrumentation and informatics Smaller is better—And other developments . 27 Dealing with the data . 30 ETHICAL, LEGAL, AND SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS . 32 An essential dimension of genome research Foreword T THE END OF THE ROAD in Little has been rapid, and it is now generally agreed Cottonwood Canyon, near Salt that this international project will produce Lake City, Alta is a place of the complete sequence of the human genome near-mythic renown among by the year 2005. A skiers. In time it may well And what is more important, the value assume similar status among molecular of the project also appears beyond doubt. geneticists. In December 1984, a conference Genome research is revolutionizing biology there, co-sponsored by the U.S. Department and biotechnology, and providing a vital of Energy, pondered a single question: Does thrust to the increasingly broad scope of the modern DNA research offer a way of detect- biological sciences. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0113561 A1 Von Melchner Et Al

US 2009.0113561A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0113561 A1 Von Melchner et al. (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 30, 2009 (54) GENE TRAP CASSETTES FOR RANDOM (30) Foreign Application Priority Data AND TARGETED CONDITIONAL GENE NACTIVATION Nov. 26, 2004 (EP) .................................. O4O281941 Apr. 18, 2005 (EP) .................................. O5103092.2 (75) Inventors: Harald Von Melchner, Publication Classification Kronberg/Taunus (DE); Frank (51) Int. Cl Schnutgen, Alzenau (DE); AOIK 67/027 (2006.01) Particia Ruiz, Berlin (DE): Silke CI2N 15/87 (2006.01) De-Zolt, Rodenbach (DE); Thomas CI2O I/68 (2006.01) Floss, Oberappersdorf (DE); Jens CI2N 5/06 (2006.01) Hansen, Kirchheim (DE) (52) U.S. Cl. .............. 800/3:536/23.1; 435/325; 800/13; 435/455: 800/25; 435/6:435/463 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT NORRIS, MCLAUGHILIN & MARCUS, PA 875 THIRDAVENUE, 18TH FLOOR A new type of gene trap cassette, which can induce condi NEW YORK, NY 10022 (US) tional mutations, relies on directional site-specific recombi nation systems, which can repair and re-induce gene trap (73) Assignee: FRANKGEN mutations when activated in Succession. After the gene trap cassettes are inserted into the genome of the target organism, BIOTECHNOLOGIE AG, mutations can be activated at a particular time and place in Kronberg (DE) Somatic cells. The gene trap cassettes also create multipur pose alleles amendable to a wide range of post-insertional (21) Appl. No.: 11/720,231 modifications. Such gene trap cassettes can be used to muta tionally inactivate all cellular genes temporally and/or spa (22) PCT Filed: Nov. -

Functional Dependency Analysis Identifies Potential Druggable

cancers Article Functional Dependency Analysis Identifies Potential Druggable Targets in Acute Myeloid Leukemia 1, 1, 2 3 Yujia Zhou y , Gregory P. Takacs y , Jatinder K. Lamba , Christopher Vulpe and Christopher R. Cogle 1,* 1 Division of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610-0278, USA; yzhou1996@ufl.edu (Y.Z.); gtakacs@ufl.edu (G.P.T.) 2 Department of Pharmacotherapy and Translational Research, College of Pharmacy, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610-0278, USA; [email protected]fl.edu 3 Department of Physiological Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610-0278, USA; cvulpe@ufl.edu * Correspondence: [email protected]fl.edu; Tel.: +1-(352)-273-7493; Fax: +1-(352)-273-5006 Authors contributed equally. y Received: 3 November 2020; Accepted: 7 December 2020; Published: 10 December 2020 Simple Summary: New drugs are needed for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML). We analyzed data from genome-edited leukemia cells to identify druggable targets. These targets were necessary for AML cell survival and had favorable binding sites for drug development. Two lists of genes are provided for target validation, drug discovery, and drug development. The deKO list contains gene-targets with existing compounds in development. The disKO list contains gene-targets without existing compounds yet and represent novel targets for drug discovery. Abstract: Refractory disease is a major challenge in treating patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Whereas the armamentarium has expanded in the past few years for treating AML, long-term survival outcomes have yet to be proven. To further expand the arsenal for treating AML, we searched for druggable gene targets in AML by analyzing screening data from a lentiviral-based genome-wide pooled CRISPR-Cas9 library and gene knockout (KO) dependency scores in 15 AML cell lines (HEL, MV411, OCIAML2, THP1, NOMO1, EOL1, KASUMI1, NB4, OCIAML3, MOLM13, TF1, U937, F36P, AML193, P31FUJ). -

Renoprotective Effect of Combined Inhibition of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme and Histone Deacetylase

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Renoprotective Effect of Combined Inhibition of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme and Histone Deacetylase † ‡ Yifei Zhong,* Edward Y. Chen, § Ruijie Liu,*¶ Peter Y. Chuang,* Sandeep K. Mallipattu,* ‡ ‡ † | ‡ Christopher M. Tan, § Neil R. Clark, § Yueyi Deng, Paul E. Klotman, Avi Ma’ayan, § and ‡ John Cijiang He* ¶ *Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York; †Department of Nephrology, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai, China; ‡Department of Pharmacology and Systems Therapeutics and §Systems Biology Center New York, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York; |Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas; and ¶Renal Section, James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center, New York, New York ABSTRACT The Connectivity Map database contains microarray signatures of gene expression derived from approximately 6000 experiments that examined the effects of approximately 1300 single drugs on several human cancer cell lines. We used these data to prioritize pairs of drugs expected to reverse the changes in gene expression observed in the kidneys of a mouse model of HIV-associated nephropathy (Tg26 mice). We predicted that the combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and a histone deacetylase inhibitor would maximally reverse the disease-associated expression of genes in the kidneys of these mice. Testing the combination of these inhibitors in Tg26 mice revealed an additive renoprotective effect, as suggested by reduction of proteinuria, improvement of renal function, and attenuation of kidney injury. Furthermore, we observed the predicted treatment-associated changes in the expression of selected genes and pathway components. In summary, these data suggest that the combination of an ACE inhibitor and a histone deacetylase inhibitor could have therapeutic potential for various kidney diseases. -

Building Transcriptional Complexes

Building transcriptional complexes Alan C. M. Cheung1,2 1. University College London, Institute of Structural and Molecular Biology, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT 2. Birkbeck College, Institute of Structural and Molecular Biology, Malet St, London, WC1E 7HX The intertwined structure of the TFIID subcomplex Taf5-Taf6-Taf9 is dependent on chaperonin CCT for its assembly and subsequent integration into the TFIID general transcription factor. Large protein complexes are ubiquitous in eukaryotic transcription, functioning in all phases of the transcription cycle, but little is known about their assembly pathways. Protein complexes require ordered pathways for their assembly1, as misassembly can result in cellular stress and cytotoxicity2. In this issue, Antonova et al. reveal a key step in the biogenesis of the TFIID complex that requires the CCT chaperonin complex (Figure 1). The TFIID complex is a general transcription factor required for recognition of the core promoter and subsequent nucleation of the RNA Polymerase II containing Pre-Initiation Complex. It is related to the SAGA complex which stimulates transcription by catalyzing histone modifications, and also by recruitment of the TATA-binding protein (TBP)3. Their relationship is due to their sharing of subunits, which is a recurrent theme amongst transcription-related complexes4. In yeast, TFIID consists of 14 subunits (TBP plus TAFs 1- 13) and shares five of these TAFs with the 19-subunit SAGA complex (specifically, TAFs 5, 6, 9, 10 and 12) whereas mammalian TFIID and SAGA only share three TAFs due to duplication of the TAF5 and TAF6 genes, resulting in paralogs TAF5L and TAF6L that specifically associate with SAGA5,6, whereas TAF5 and TAF6 are incorporated into TFIID.