The Leisure Activities of the Rural Working Classes with Special

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Local Government Boundary Commision for England Electoral Review of South Norfolk

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF SOUTH NORFOLK E Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the district of South Norfolk March 2017 Sheet 1 of 1 OLD COSTESSEY COSTESSEY CP EASTON CP D C This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of the Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majestry's Stationary Office @ Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil preceedings. NEW COSTESSEY The Local Governement Boundary Commision for England GD100049926 2017. B Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest Boundary information MARLINGFORD AND COLTON CP applied as part of this review. BAWBURGH CP BRANDON PARVA, COSTON, A RUNHALL AND WELBORNE CP EASTON BARNHAM BROOM CP BARFORD CP COLNEY CP HETHERSETT TROWSE WITH LITTLE MELTON CP NEWTON CP SURLINGHAM CP GREAT MELTON CP KIRBY BEDON CP CRINGLEFORD WRAMPLINGHAM CP CRINGLEFORD CP KIMBERLEY CP HETHERSETT CP BIXLEY CP WICKLEWOOD BRAMERTON CP ROCKLAND ST MARY CP KESWICK AND INTWOOD CP PORINGLAND, ROCKLAND FRAMINGHAM FRAMINGHAMS & TROWSE PIGOT CP H CAISTOR ST EDMUND CP H CLAXTON CP NORTH WYMONDHAM P O P C L C M V A E H R R C S E G T IN P O T ER SWARDESTON CP N HELLINGTON E T FRAMINGHAM YELVERTON P T CP KE EARL CP CP T S N O T E G EAST CARLETON CP L WICKLEWOOD CP F STOKE HOLY CROSS CP ASHBY ST MARY CP R A C ALPINGTON CP HINGHAM CP PORINGLAND CP LANGLEY WITH HARDLEY CP HINGHAM & DEOPHAM CENTRAL -

Keswick and Intwood Parish Council Meeting on 25 November 2009

Keswick and Intwood Parish Council Meeting on 25th November 2009. Minutes of the meeting held at The Reading Rooms, Keswick at 19.00. Present: Alan Gelder (AG); Joe Loades (JL); Kevin Hanner (KH); Ruth Ripman (RR); Hayley Spouge (HS) and Phillip Brooks (PB) (Clerk). Also Present: Oliver Butcher (PCSO); Tim Philpott (PCSO); and members of the public: Marguerite Russell (MR) and Olive Dick (OD). Apologies were received from: Christopher Kemp (Councillor Cringleford Ward) (CK); Garry Wheatley (Councillor Cringleford Ward) (GW) and Daniel Cox (Norfolk County Councillor) (DC). 1. To consider apologies for absence: Resolved to accept apologies from Lars Tibell (LT) and Diana Bulman (DB) both unavoidable away from Norwich. AG said that DB had informed him that she would be resigning from the Council because of the amount of time she was now spending away from Norwich. Kevin Hanner was co-opted as a member of the Parish Council. PB reminded the Council that this was the last declared meeting before AG resigned his position as Councillor and Chairman in the New Year. RR said she was willing to assume the position on AG’s resignation. 2. To receive declaration of interests in items on the Agenda: No interests were declared. 3. Public Participation. It was resolved to adjourn the meeting for public participation: MR said she was concerned about the track and path through Big Wood which had been blocked to walkers by gates installed by the landowner. They were regularly used for leisure walking (OD indicated there had been contact with the Ramblers Association in this regard) but they were also functional in providing a safe route on foot between Keswick New Hall and Low Road. -

Council Tax Rates 2020 - 2021

BRECKLAND COUNCIL NOTICE OF SETTING OF COUNCIL TAX Notice is hereby given that on the twenty seventh day of February 2020 Breckland Council, in accordance with Section 30 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992, approved and duly set for the financial year beginning 1st April 2020 and ending on 31st March 2021 the amounts as set out below as the amount of Council Tax for each category of dwelling in the parts of its area listed below. The amounts below for each parish will be the Council Tax payable for the forthcoming year. COUNCIL TAX RATES 2020 - 2021 A B C D E F G H A B C D E F G H NORFOLK COUNTY 944.34 1101.73 1259.12 1416.51 1731.29 2046.07 2360.85 2833.02 KENNINGHALL 1194.35 1393.40 1592.46 1791.52 2189.63 2587.75 2985.86 3583.04 NORFOLK POLICE & LEXHAM 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 175.38 204.61 233.84 263.07 321.53 379.99 438.45 526.14 CRIME COMMISSIONER BRECKLAND 62.52 72.94 83.36 93.78 114.62 135.46 156.30 187.56 LITCHAM 1214.50 1416.91 1619.33 1821.75 2226.58 2631.41 3036.25 3643.49 LONGHAM 1229.13 1433.99 1638.84 1843.70 2253.41 2663.12 3072.83 3687.40 ASHILL 1212.28 1414.33 1616.37 1818.42 2222.51 2626.61 3030.70 3636.84 LOPHAM NORTH 1192.57 1391.33 1590.09 1788.85 2186.37 2583.90 2981.42 3577.70 ATTLEBOROUGH 1284.23 1498.27 1712.31 1926.35 2354.42 2782.50 3210.58 3852.69 LOPHAM SOUTH 1197.11 1396.63 1596.15 1795.67 2194.71 2593.74 2992.78 3591.34 BANHAM 1204.41 1405.14 1605.87 1806.61 2208.08 2609.55 3011.01 3613.22 LYNFORD 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 -

River Glaven State of the Environment Report

The River Glaven A State of the Environment Report ©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative ©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence © Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this C reative ©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence Produced by Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service Spring 201 4 i Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service (NBIS) is a Local Record Centre holding information on species, GEODIVERSITY , habitats and protected sites for the county of Norfolk. For more information see our website: www.nbis.org.uk This report is available for download from the NBIS website www.nbis.org.uk Report written by Lizzy Oddy, March 2014. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank the following people for their help and input into this report: Mark Andrews (Environment Agency); Anj Beckham (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Andrew Cannon (Natural Surroundings); Claire Humphries (Environment Agency); Tim Jacklin (Wild Trout Trust); Kelly Powell (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Carl Sayer (University College London); Ian Shepherd (River Glaven Conservation Group); Mike Sutton-Croft (Norfolk Non-native Species Initiative); Jonah Tosney (Norfolk Rivers Trust) Cover Photos Clockwise from top left: Wiveton Bridge (©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Glandford Ford (©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); River Glaven above Glandford (©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Swan at Glandford Ford (© Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence). ii CONTENTS Foreword – Gemma Clark, 9 Chalk Rivers Project Community Involvement Officer. -

Little Ouse and Waveney Project

Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Mott MacDonald Norfolk County Council Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Little Ouse and Waveney Project May 2006 214980-UA02/01/B - 12th May 2006 Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Mott MacDonald Norfolk County Council Transnational Ecological Network (TEN3) Little Ouse and Waveney Project Issue and Revision Record Rev Date Originator Checker Approver Description 13 th Jan J. For January TEN A E. Lunt 2006 Purseglove workshop 24 th May E. Lunt J. B Draft for Comment 2006 Purseglove This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any o ther project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Mott MacDonald being obtained. Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequence of this document being used for a pur pose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person using or relying on the document for such other purpose agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm his agreement to indemnify Mott MacDonald for all loss or damage re sulting therefrom. Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for this document to any party other than the person by whom it was commissioned. To the extent that this report is based on information supplied by other parties, Mott MacDonald accepts no liability for any loss or damage suffered by the client, whether contractual or tortious, stemming from any conclusions based on data supplied by parties other than Mott MacDonald and used by Mott MacDonald in preparing this report. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List Of

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List of 1471412 It 44 Norfolk Census 1851 Index 6115160 Norfolk Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It 1 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1811-1825 375230 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1825-1839 375231 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1839-1859 375232 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1715-1734 1596461 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1734-1749 1596462 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1770-1774 1596563 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1774-1781 1596564 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1790-1797 1596566 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1798-1803 1596567 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1812-1819 1596597 Norfolk Marriages Parish Registers 1539-1812 496683 It 2 Norfolk Probate Inventories Index 1674-1825 1471414 It 17-20 Norfolk Tax Assessments 1692-1806 1471412 It 30-43 Norfolk Wills V.101 1854-1857 167184 Norfolk Alburgh Parish Register Extracts 1538-1715 894712 It 5 Norfolk Alby Parish Records 1600-1812 1526778 It 15 Norfolk Aldeby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 6 Norfolk Alethorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Arminghall Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Ashby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 7 Norfolk Ashby Parish Register Extracts 1646 894712 It 5 Norfolk Ashwell-Thorpe Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Aslacton Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Baconsthorpe Parish Register Extracts 1676-1770 894712 It 6 Norfolk Bagthorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Bale Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Bale Parish Register Extracts 1538-1716 894712 It 6 Norfolk Barmer Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barney Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barton-Bendish Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It -

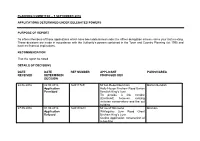

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE of REPORT to Inform Members of Th

PLANNING COMMITTEE – 5 SEPTEMBER 2016 APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATED POWERS PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform Members of those applications which have been determined under the officer delegation scheme since your last meeting. These decisions are made in accordance with the Authority’s powers contained in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 and have no financial implications. RECOMMENDATION That the report be noted. DETAILS OF DECISIONS DATE DATE REF NUMBER APPLICANT PARISH/AREA RECEIVED DETERMINED/ PROPOSED DEV DECISION 24.06.2016 22.08.2016 16/01172/F Mr Ian-Robert Bercham Barton Bendish Application Holly House Fincham Road Barton Permitted Bendish King's Lynn To provide a link corridor (Enclosed) between existing victorian conservatory and the out building. 27.05.2016 01.08.2016 16/01014/O Mr Geoff Simmons Bircham Application Whitegates Lynn Road Great Refused Bircham King's Lynn Outline Application: construction of a dwelling 05.05.2016 04.08.2016 16/00856/F Mr P Youel Boughton Application Kingston House Chapel Road Permitted Boughton Norfolk Single storey rear extension to dwelling 03.06.2016 21.07.2016 16/01040/F Mr & Mrs T Scrivener Boughton Application Church Farm Barn The Green Permitted Boughton Norfolk Construction of domestic garage 24.06.2016 18.08.2016 16/01175/F Mr & Mrs I Davis Boughton Application Hall Farm Cottage Mill Hill Road Permitted Boughton King's Lynn External wall insultation and render facing to exposed original cottage walls 10.06.2016 22.08.2016 16/01095/F Mr Tim Williams Brancaster Application Bramble -

Stalham Farmers Opening Meeting 2018-19 Season at Vera's Coffee

Stalham Farmers Opening Meeting 2018-19 season at Vera’s Coffee Shop Wednesday, November 14. At the first indoor meeting of the 177th season, the chairman, Henry Alston welcomed 34 members and guests including the guest speaker, Jake Fiennes, to the new venue. Supper was served at the new venue, Vera’s Coffee Shop at AG Meale & Sons nursery at Wayford Bridge, which was much appreciated by the 14 strong-strong company. The meeting was called to order at 7.40pm Remembrance: Members were asked to stand in memory of our former president, William Donald, and former members including George Morton and John Withers. Apologies – Robert Gray, Geoff Beck, Rob Baines, Sir William Cubitt, Jason Cantrill, Tim Papworth, Christopher Deane, Ken Leggett, Roy Houlden, Jo and Ian Willetts. Chairman’s report – A visit to the Strumpshaw estate and the part of the adjoining nature reserve had been enjoyed by some 80 members and guests. The tour of the estate’s museum had been especially appreciated and the opportunity to enjoy some many of the rides too. In October, 20 members had visited Kettle Foods at Bowthorpe, Norwich, which had been a fascinating tour of the operations. A £3m investment as about to start, said Mr Alston. New members – A total of six members were duly elected. Ben Catling and Neil Punchard, Andrew Claydon, David Pickering, Charlotte Hovey and Harold Dustan. They were proposed by Will Sands and Chris Borrett and agreed. Secretary’s report – Michael Pollitt said that entries for the club’s grain competition would close at the December meeting, when samples could be brought or left at Adams & Howling or at Neal Sands’ factory. -

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 Socc Stakeholder Mailing List

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 20.3 SoCC Stakeholder Mailing List Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: 5.1 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2018 Revision: Version 1 Author: BECG Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Appendices Parish Councils Bacton and Edingthorpe Parish Council Witton and Ridlington Parish Council Brandiston Parish Council Guestwick Parish Council Little Witchingham Parish Council Marsham Parish Council Twyford Parish Council Lexham Parish Council Yaxham Parish Council Whinburgh and Westfield Parish Council Holme Hale Parish Council Bintree Parish Council North Tuddenham Parish Council Colkirk Parish Council Sporle with Palgrave Parish Council Shipdham Parish Council Bradenham Parish Council Paston Parish Council Worstead Parish Council Swanton Abbott Parish Council Alby with Thwaite Parish Council Skeyton Parish Council Melton Constable Parish Council Thurning Parish Council Pudding Norton Parish Council East Ruston Parish Council Hanworth Parish Council Briston Parish Council Kempstone Parish Council Brisley Parish Council Ingworth Parish Council Westwick Parish Council Stibbard Parish Council Themelthorpe Parish Council Burgh and Tuttington Parish Council Blickling Parish Council Oulton Parish Council Wood Dalling Parish Council Salle Parish Council Booton Parish Council Great Witchingham Parish Council Aylsham Town Council Heydon Parish Council Foulsham Parish Council Reepham -

Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction

National Trail 20 Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction The walks in this guide are designed to make the most of the please be mindful to keep dogs under control and leave gates as natural beauty and cultural heritage of the Norfolk coast. As you find them. companions to stretch one and two of the Norfolk Coast Path (part of the England Coast Path), they are a great way to delve Equipment deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful Depending on the weather, some sections of these walks can array of landscapes and habitats await, many of which are be muddy. Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or home to rare wildlife. The architectural landscape is expansive shoes is essential for the longer routes. Norfolk’s climate is drier too. Churches dominate, rarely beaten for height and grandeur than much of the country but unfortunately we can’t guarantee among the peaceful countryside of the coastal region, but sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you there’s much more to discover. are lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget From one mile to nine there’s a walk for everyone here, whether sun cream and a hat. you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. Many of these routes lend themselves well to The walks described in these pages are well signposted on the trail running too. With the Cromer ridge providing the greatest ground, and detailed downloadable maps are available for elevation of anywhere in East Anglia, it’s a great way to get fit as each at www.norfolktrails.co.uk. -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633.