Indicators of Rainforest Recovery from Disturbance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2015 HUT NEWS January 2016 “Nature Conservation Saves for Tomorrow”

Blue Mountains Conservation Society Inc. Issue No. 332 December 2015 HUT NEWS January 2016 “Nature Conservation Saves for Tomorrow” Oppose the Western Sydney 90% renewable energy plan Airport proposal The Australian Greens has launched a plan to transition Australia to at The Draft Environmental Impact State- least 90% renewable energy by 2030. The plan offers two scenarios, ment (EIS) for the proposed Western both of which see a new government authority called RenewAustralia Sydney Airport can be found on http:// set up to help drive the transition. It can be viewed at http:// westernsydneyairport.gov.au/resources/ renewaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/ deis/index.aspx sites/16/2015/11/2015_11_Renew_Australia.pdf Submissions close on 18 December The party says their plan will create tens of thousands of jobs in the design and construction of new renewable energy generation, plus 2015. employment in operations and maintenance. The Greens also intend The Draft EIS glosses over most of the putting a price back on carbon, saying it is essential to Australia’s future threats facing the Greater Blue prosperity. Mountains. The two pathways offered aim to reduce Australia’s overall greenhouse Impacts on the World Heritage listed emissions by at least 29% between now and 2030. Blue Mountains and Declared Wilderness Areas through air, noise and water pollution are unacceptable. BMCS Native Plant Nursery—Volunteers at work The EIS fails to recognise the value of Customers at quiet places for nature and for our tourist our nursery’s industry. Aircraft are not an stall at the environmentally sustainable form of Blackheath transport. -

Waterfall Way Corridor Strategy

B78 WATERFALLWAY DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY JULY 2017 WATERFALL WAY DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY July 2017 Waterfall Way DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY Draft for consultation I Draft only: actions subject to government priorities and funding availability B78 WATERFALL WAY DRAFT CORRIDOR STRATEGY JULY 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE Heading east through Bellingen Main Street The Waterfall Way Corridor is during consultation will inform future planning, final actions will be subject to government located in Northern NSW and priorities and funding availability. extends from the Pacific Highway The Waterfall Way provides: at Raleigh to the NewDraft England for Highway at Armidale a distance of • The Waterfall Way is an important transport corridor, providing an east – west connection 170km. Traffic volumes along the between the Pacific and New England Waterfall Way vary in the rural highways. It connects rural communities to the sections from around 750 vehicles urban centres of Coffs Harbour and Armidale per day (vpd) betweenconsultation Dorrigo • It is a tourist route passing the waterfalls on the Dorrigo Mountain and provides access to the and Ebor to over 6,700vpd Dorrigo National Park between the Pacific Highway and • A transport route for the timber and Bellingen. agricultural industries. Key customers along the corridor include: This draft sets out the proposed strategic vision to manage and guide development of the Waterfall • Commuters; trips to urban centres, such as Way road corridor to improve safety, traffic Coffs Harbour, for employment and education efficiency and sustainability. There is no • Longer personal and work related educational, commitment to, or funding for, proposed actions health, recreational and business trips; identified in this draft. -

The Distribution of a Flute-Like Dialect in Territorial Songs of the Superb

Corella, 2019, 43: 1-7 The distribution of a flute-like dialect in territorial songs of the Superb Lyrebird Menura novaehollandiae in the New South Wales North Coast and New England Tableland Bioregions Hollis Taylor1, Vicki Powys2, and Carol Probets3 157-B Chaseling Avenue, Springwood NSW 2777 (Email: [email protected]) 21897C Glen Davis Rd, Capertee NSW 2846, 3PO Box 330, Katoomba NSW 2780 Received: 16 February 2018 Accepted: 25 July 2018 On-site recordings were made and field data obtained on the territorial songs of the Superb Lyrebird Menura novaehollandiae at 100+ sites in forests of the New South Wales North Coast and New England Tableland Bioregions during winter from 2009-2014. Songs were categorized as either ‘flute-like’ or not flute-like, and the two song types are compared. Maps are presented that define the geographical extent of the flute-like dialect. The study demonstrates that the flute-like song extends over a wider area than previously thought, but the exact place of origin remains unknown. Some interesting discontinuities in the distribution of this song dialect are discussed. INTRODUCTION The current study builds on the only suggested example of Superb Lyrebird imitation of a man-made sound in territorial The vocal repertoire of the Superb Lyrebird Menura song (Robinson 1975; Reilly 1988; Smith 1988; Rankin et al. novaehollandiae includes mimicry (mostly of other birds 1999). Powys et al. (2013) investigated the cultural history of a such as the Laughing Kookaburra Dacelo novaeguineae, Superb Lyrebird chick that was purportedly raised in captivity Pied Currawong Strepera graculina, and Crimson Rosella in the 1920s in Australia’s New England Tablelands. -

Coffs Coast Regional

TO GLEN TO NYMBOIDA TO McPHERSONS TO GRAFTON INNES 28km ABCDE3km CROSSING 26km FTO GRAFTON 36km 41km G YURAYGIR HORTONS NAT PK CK NAT N WARRA 152º50'E Red Rock 152º10'E 153º10'E 151º50'E 152º00'E 153º00'E 152º20'E 152º30'E 152º40'E NAT PK (locality) RES o TOURIST DRIVE 19 rt Kookabookra h YARRAWARRA CHAELUNDI KA 30º00'S SHEAS NG ABORIGINAL 1 RED ROCK STATE FOREST 996 CHAELUNDI AR GUY FAWKES NOB SF 803 O CULTURAL CENTRE NATIONAL O HOLIDAY PARK Ben Lomond PARK RIVER k k e Towallum e e r e P Y r R Corindi Beach A C D IV C E Glenreagh SHERWOOD CORINDI BEACH R R W Fawkes BYRNES NAT RES H HOLIDAY PARK CLOUDS CREEK SCRUB Upper G LLANGOTHLIN I 10 O Corindi RD NAT RES H For detail see Map 8 N R LAKE The T Chaelundi Ck a E (locality) A MARENGO A Arrawarra Platypus are found in most RD l R W R Rest Area Junction l SF 318 a A Backwater K pools along the river 4WD beach access 12 LITTLE R w 1 O E KANGAROO Coast 1 u WEDDING LLANGOTHLIN O V B um I d BELLS Mullaway A s j NAT RES s R a K po RIVER CONGLOMERATE O h Woolgoolga Beach O Clouds Creek 12 O CHAELUNDI RD 4WD beach access K River an ST CONS Railway b NYMBOI - BINDERAY Railway Oban O SF 21 SF 349 For detail Woolgoolga AREA NATIONAL PARK GENTLE ANNIE see Map 3 s SF 111 d Little FOREST WAY n a Ma ELLIS SF 831 N uc l Riv re Misty Creek O B ca SOLITARY w er n T RD o g Lookout Vista Point F Cod Hole N o Woolgoolga ISLANDS Llangothlin MIST A Bucca Wards Mistake R A N Nana Glen Creek Picnic AKE Marengo Falls G y Hearnes Lake (locality) D m BAGAWA SF 30 13 Area NATIONAL I R Lower b WILD I S O V o Bucca Sandy Beach GARA D Ck i MT E For detail B d R CATTLE BUSHMANS R Sandy Beach A PARK HYLAND M a RD see Map 9 W CREEK Moleton SF NAT RES Y 11 Fiddamans Beach 318 N SF 488 LOWER M Billys Creek Platypus SF Emerald Beach 30º10'S A BUCCA le T 11 oy R Flat 536 Look at Me Now f 10 r DR e E S Headland b SF 29 E A N R A R 5 k G N Ck O MOONEE BEACH e O FO G R E F e 23 EST MOTHER OF DUCKS r Dundarrabin NATURE RESERVE P Norman Jolly R. -

Dorrigo-Chamber-Of-Commerce-Waterfall-Way-Road-Policy-Issue-1-21JAN2019-PL.Pdf

Dorrigo Chamber of Commerce Inc. Policy name: Dorrigo Chamber of Commerce Waterfall Way Road Policy Policy Version: Issue 1 Adopted at Chamber meeting: 21 st January 2019 1 Background Waterfall Way is a sealed east-west roadway connecting the coastal Pacific Highway to the New England region. It is 170km in length extending from Raleigh in the east to Armidale in the west. The majority of traffic movements are between Raleigh and Dorrigo in the east, and locally in the built-up area of Armidale in the west. Waterfall Way is a roadway of one lane in each direction with following exceptions: • Three shared one-lane sections at Newell Falls, Sherrard Falls, and a section between these two falls. • Six formal overtaking lanes (3 eastbound and 3 westbound) all located west of Ebor. It is the primary access route serving Dorrigo. It has been the lifeblood of the town for more than a century. Sections of the road are steep with many bends, particularly between Dorrigo and Thora. Considerable constraints to road construction and maintenance are due to the geology, topography, high seasonal rainfall, and environmental management, especially in the World Heritage area through the Dorrigo National Park. Waterfall Way is a major tourist route as well as servicing as a lively commercial and private corridor. For many road users, especially overseas tourists, Waterfall Way is the first high-speed un- divided country road they encounter after exiting the Pacific Highway. Drivers with limited experience navigating narrow and winding roads with large caravans and recreational vehicles (RV’s) present challenges for all road users. -

N Coffs Harbour

To Inverell To Glen Innes, Brisbane To Grafton To Grafton To Brisbane Glenreagh Upper Arrawarra Warra Sheas Nob Corindi National Park State Forest 15 Guy Fawkes River RD Mullaway National Park Marengo Kangaroo River Tingha State Forest The Junction State Forest Locked Chaelundi Clouds gate Tingha Single Creek Woolgoolga Stone Woman Nymboi National Park Ben Lomond Llangothlin Binderay Lake National Sandy Beach River Park Backwater Ellis State Forest Bagawa Nana Misty Creek State Forest Glen Emerald Beach Guy 1 Little Llangothlin Guy Fawkes River Lookout Wandsworth Nature Reserve National Park GRAFTON Mount Wild Cattle Creek Moonee Beach HWY Wards Hyland State Forest Fawkes Platypus Flat Indwarra Mistake Nature Billys Creek Nature Reserve Reserve Lowanna Sapphire Beach Tenterden Llangothlin Mobong Picnic Area Coramba Dundurrabin Norman Jolly Tibbs Tree Tyringham Memorial Ulong TYRINGHAM RD Korora Hyland Cascade Karangi State Forest Cascade Nymboida National Park Dairyville The Basin Brooklana HWY Nature Reserve Aberfoyle RD Upper River ENGLAND Orara Dunvegan Coffs Harbour Bundarra Megan Bindarri Bostobrick National Park River North Junuy Juluum CORAMBA Guyra Aberfoyle Dorrigo National Park OLD EBOR Rampsbeck i Dorrigo Mother of Ducks GUYRA Hernani Locked gate Boambee Lagoon Dangar Falls National Park Toormina Nature Reserve Wongwibinda Guy Fawkes River Malpas 17 RD National Park Gangara Dorrigo Crossmaglen PACIFIC Dam i Never Never Sawtell 17 Lyndhurst Deer Picnic Area Baldersleigh Dorrigo Rainforest Centre Bonville Gwydir Black 78 Vale -

Waterfall Way Safety Review and Program Update

Community update MARCH 2014 Waterfall Way safety review and program update Waterfall Way is an important route connecting the mid north coast and Coffs Harbour district with the coastal hinterland of Bellingen, Dorrigo, Armidale, and beyond. The NSW Centre for Road Safety and Roads and Maritime Services recently announced a review of road safety along Waterfall Way. This update contains information about the review, including a feedback form, and information about the various projects along Waterfall Way. Newell Falls Safety review On 27 February we announced a Waterfall Way A feedback form is attached to this community road safety review after community feedback about update for people to either bring to the drop-in increased truck movements along the road. sessions, or mail to the project team. The form is also available online. The review, in partnership with the community and other relevant stakeholders, will examine all aspects The drop-in sessions will be followed by two of safety on the 40 kilometre stretch of road from community workshops, which will discuss issues Dorrigo to the junction of the Pacific Highway. It will raised by the community, provide information not examine bypassing the Bellingen township. The about crash trends, statistics and vehicle review’s findings will be used to develop a strategy movements as well as identify sites to be inspected. to improve road safety on Waterfall Way in the short The first of these workshops will be held in May, to medium term. with the date to be advised. Community members are invited to contribute to the A copy of the review team’s findings and review through “drop-in” sessions, workshops, and recommendations will be available on the internet. -

Waterfall Way

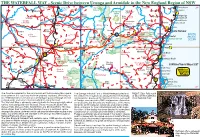

THE WATERFALL WAY - Scenic Drive between Urunga and Armidale in the New England Region of NSW º 30º Nymboida Ben Lomond Llangothlin Guy Fawkes Towallum Corinda Beach 33º 26 Lake Backwater 152 National Park Arrawarra Wandsworth 27 Mt Hyland Clouds 45 Glenreagh 13 Nature Creek Wards Res. 25 100 Mistake Billys Nana Glen Woolgoolga Tenterden Llangothlin Marengo Creek 117 11 Sandy Beach Bundarra Plain Georges Lowanna Emerald Beach HWY Dundurrabin 5 V Mountain 27 River Coramba Moonee Beach Tyr ingham Old Store Ulong Guyra Monkey Point V Cascade 15 Aberfoyle Gwydir 28 36 30 57 Korora 12 Wongwibinda 21 Megan Baldersleigh Black Hernani Bostobrick Brooklana 17 Abington Mountain Coffs Harbour 48 Dangar FallsDorrigo 34 Boambee 38 V Pine V Joey Knob Ebor 78 38 Dorrigo Nat Pk SOUTH Falls 13 Way 93 Rainforest Centre Bonville Mountain Cathedral Rock Sawtell PACIFIC Fernbrook 31 Valery 27 Mt Davidson National Park Ebor Sherrard Falls Thora Bongil Bongil Nat Park OCEAN Mitchells V V Terryburn Cathedral Rock Majors Point Repton Flat aterfall Point Darkwood Newell Raleigh 12 Yarrowyck W Falls Bellingen Mylestom 37 15 Lookout 11 River 32 Wollomombi River Kingstown Armidale Way Urunga Waterfall 80 Brierfield Bellinger Mt Gladstone V Newry 22 43 New England V Missabotti 28 25 Jeogla National Park Killiekrankie State Valla Beach 25 Rocky Forest Valla River 15 Hillgrove Wollomombi Mountain 24 Gorge Bowraville 120 Castle 45 14 Nambucca Heads 17 Doyle Oxley Wild Rivers Uralla Dangars 13 Watsons 43 Falls National Park Five Day 'The Pub WithTaylors Creek Creek Arm -

Dorrigo National Park Plan of Management

DORRIGO NATIONAL PARK PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service October 1998 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 4 October 1998. Acknowledgements: This plan of management has been prepared by staff of the Dorrigo District Office of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Crown Copyright 1998. Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgement. ISBN 0 7310 7688 5 FOREWORD Dorrigo National Park has an area of 7 885 hectares and is located 4 kilometres east of Dorrigo township which in turn lies 590 kilometres by road from Sydney. Dorrigo township is the centre of the rich agricultural lands of the Dorrigo Plateau. The town of Bellingen lies 25 kilometres to the east of the park and is the main town servicing the Bellinger Valley. The mid-north coast is within one hours drive of the park with the increasing population of centres such as Coffs Harbour and Nambucca Heads an important factor in park use and management. Part of Dorrigo Mountain was first protected in 1901. The area of reserved lands was progressively enlarged and granted increased protection until in 1967 when it was reserved under the National Parks and Wildlife Act, 1967 as a State Park. Under the National Parks and Wildlife Act of 1974 Dorrigo State Park was accorded national park status. In 1986 it was incorporated in the World Heritage List as one of the Sub-tropical and Warm Temperate Rainforest Parks of Eastern Australia, now known as the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves of Australia. Dorrigo National Park is one of an important group of conservation areas on the Great Escarpment which include New England, Guy Fawkes River, Cathedral Rocks and Oxley Wild Rivers National Parks and Mount Hyland and Guy Fawkes River Nature Reserves. -

Inventory of Australian Megaloptera Larvae and Resulting Implications for the Classification of the Group (Insecta: Neuropterida)

©Biologiezentrum Linz Austria, download www.zobodat.at Inventory of Australian Megaloptera larvae and resulting implications for the classification of the group (Insecta: Neuropterida) Günther THEISCHINGER Abstract Archichauliodes. Only three of four spe- cies groups of Archichauliodes (Rie- kochauliodes) separable on the basis of adult characters, are distinguished on lar- Abstract: The information avai- val morphology. A key to the larvae of the lable on the larvae of the Australian Mega- now recognised group taxa of the Austra- loptera is presented and used for re-apprai- lian Megaloptera and distributional details sal of some supraspecific taxa. Apochauli- of most species are given in order to initia- odes THEISCHINGER, formerly described as te more thorough studies. a subgenus of Archichauliodes WEELE is accorded full generic status. A new subge- nus, Riekochauliodes, is established for Key words: Megaloptera, Aus- the majority of the Australian species of tralia, larvae, classification. Stapfia 60, zugleich Kataloge des OÖ. Landesmuseums, Neue Folge Nr. 138 (1999), 85-100 85 ©Biologiezentrum Linz Austria, download www.zobodat.at Introduction Systematics Some information on the taxonomy of the Family Corydalidae (Figs 1-47) larvae of the Australian Megaloptera was Remarks: All Australian Corydalidae given in the first revision of the group (RlEK belong to the subfamily Chauliodinae. 1954). Presentation of accumulated informati- Larvae: Abdomen with 8 pairs of late- on on the larvae was announced for the futu- ral processes (gills); apical segment of abdo- re in a more comprehensive treatment of the men with pair of prolegs but without terminal adults (THE1SCHINGER 1983). In the meantime and afterwards, keys to the larvae of families filament. -

Bellinger River National Park Plan of Management

BELLINGER RIVER NATIONAL PARK PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service May 2000 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 15th May 2000. Acknowledgments: This plan of management was prepared by staff of the Northern Region of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. Acknowledgment is made of the specialist advice provided by Lachlann Ison, John Hunter and Phil Gilmour in the preparation of the draft plan of management. Members of the Bellingen community and others who provided comments on the draft plan, participated in consultation workshops or contributed to the planning process in other ways are gratefully acknowledged. Photograph of Bellinger River National Park with Bellinger River in foreground by Janelle Brooks. NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Crown Copyright 2000: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. ISBN 0 7313 6997 1 FOREWORD Bellinger River National Park is located between New England and Dorrigo National Parks, south of Dorrigo on the north coast of NSW. The park was reserved as part of the New South Wales Government’s forest reforms, which aim to establish a comprehensive, adequate and representative reserve system in NSW. Other parks in the region established under the same reforms are Chaelundi, Nymboi-Binderay and Dunggir National Parks. Bellinger River National Park forms a continuous forested link between Dorrigo and New England National Parks, both of which are included as part of the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves of Australia World Heritage Area. Bellinger River National Park is being considered for addition to this World Heritage property. The natural floral diversity of the park includes subtropical, gully and dry rainforests, creating habitat for many species of fauna. -

Autumn Edition

APS Armidale 2018 Autumn Edition Australian Plants Society Armidale & District Group PO Box 735 Armidale NSW 2350 web: http://www.aps-armidale.org.au e-mail: [email protected] Crowea exalata ssp magnifolia Image by Maria Hitchcock In this issue: Office bearers for 2017 p 2 Autumn Edition 2018 - 1 President’s Report p 3 Family Fun in the Tub p 4 Coffs to Armidale p 6 Lee’s Pinch p 7 On Leaving Yallaroo p 9 Fred Roger’s Seminar p 10 Christmas Function 2017 p 13 Hyacinth Orchids p 14 Wollemi Pine Propagation p 17 Armidale Show p 18 January in my Garden p 18 Diary of Activities p 20 Christmas 2006, Andrew Grigg with Sheathers Contact Us: Armidale & District Group PO Box 735, Armidale NSW 2350 President: Barbara Nevin Ph. 6775 3767 [email protected] Secretary: Penelope Sinclair Ph. 6771 5639 [email protected] Treasurer: Carole Fullalove Ph. 67719061 [email protected] 1 APS Armidale 2018 Autumn Edition From the Editor: This is my first newsletter for the group, so please excuse errors as I am on a steep learning curve. My thanks to Neil Wilson for handing on the job in such good shape with his digital expertise. We are sad to be losing our long term members in Gloria and Warren Sheather, who are moving to the Blue mountains. Our loss is Blue Mountains gain. I have put on the cover a photo from our christmas function in December, 2006, which was held at our youngest member’s garden that he had designed for his parents.