Biodiversity and the Challenge of Saving the Ordinary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Capital

Cultural Recommended books to read Recommended films./shows to watch Recommended places to visit capital Biology- New Scientist, National Geographic Chemistry - Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum, Lapworth museum of Beginners guide to the periodic table by Gill Arbuthnott Geology, National Science Museum and Natural History Biology: Planet Earth 1 & 2 , The Blue Planet and Blue Planet 2 , Science: A beginners encyclopaedia Museum, London, Discovery Museum, Newcastle upon Tyne, KS3 Life on Land (Attenborough Box Set) , Life , Hidden Kingdoms , All About Chemistry by Robert Winston Science squad by Robert Eden Project, Chester Zoo, Jodrell Bank Discovery Centre, Nature’s Weirdest Events , YouTube: Crash Course Biology Winston Cheshire, National Space Centre, Leicester, Centre for Alternative Technology, Machynlleth, Biology: New Scientist, National Geographical, A Short History of Nearly Everything, Bill Bryson , Life on Earth, David Attenborough ,Bad Science, BBC Science Focus magazine Chemistry - All About Chemistry by Robert Winston Science Biology: YouTube: Bozerman , Science.tv , Blackfish and Grizzly squad by Robert Winston All of the above plus EDF Energy Visitor Centres at numerous Man (Award-winning Netflix Documentaries) , Human Planet KS4 The Disappearing Spoon by Sam Kean power stations, Dinorwig Power Station, Llanberis, Culham Physics: Brian Cox BBC series - The Planets, Wonders of the Big Bang- a History of Explosives by G I Brown Centre for Fusion Energy, Oxfordshire, Universe, Human Universe etc, Science, Money and Politics -

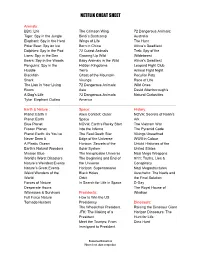

Netflix Cheat Sheet

NETFLIX CHEAT SHEET Animals: BBC: Life The Crimson Wing 72 Dangerous Animals: Tiger: Spy in the Jungle Bindi’s Bootcamp Australia Elephant: Spy in the Herd Wings of Life The Hunt Polar Bear: Spy on Ice Born in China Africa’s Deadliest Dolphins: Spy in the Pod 72 Cutest Animals Trek: Spy of the Lions: Spy in the Den Growing Up Wild Wildebeest Bears: Spy in the Woods Baby Animals in the Wild Africa’s Deadliest Penguins: Spy in the Hidden Kingdoms Leopard Fight Club Huddle Terra Animal Fight Night Blackfish Ghost of the Mountain Peculiar Pets Shark Virunga Race of LIfe The Lion in Your Living 72 Dangerous Animals: Wild Ones Room Asia David Attenborough’s A Dog’s Life 72 Dangerous Animals: Natural Curiosities Tyke: Elephant Outlaw America Earth & Nature : Space: History: Planet Earth II Alien Contact: Outer NOVA: Secrets of Noah’s Planet Earth Space Ark Blue Planet NOVA: Earth’s Rocky Start The Vietnam War Frozen Planet Into the Inferno The Pyramid Code Planet Earth: As You’ve The Real Death Star Vikings Unearthed Never Seen It Edge of the Universe WWII in Colour A Plastic Ocean Horizon: Secrets of the Untold Histories of the Earth’s Natural Wonders Solar System United States Mission Blue The Inexplicable Universe Nazi Mega Weapons World’s Worst Disasters The Beginning and End of 9/11: Truths, Lies & Nature’s Weirdest Events the Universe Conspiracy Nature’s Great Events Horizon: Supermassive Nazi Megastructures Weird Wonders of the Black Holes Auschwitz: The Nazis and World Orbit the Final Solution Forces of Nature In Search for Life in Space D-Day Desperate Hours: The Royal House of Witnesses & Survivors Presidents: Windsor Full Force Nature How to Win the US Tornado Hunters Presidency Dinosaurs: The Wheelchair President Raising the Dinosaur Giant JFK: The Making of a Horizon Dinosaurs: The President Hunt for Life Meet the Trumps: From Dino Hunt Immigrant to President HomeschoolHideout.com Please do not share or reproduce. -

Bloomsbury Children's Books • January 2022 Juvenile Fiction / Family / Multigenerational

BLOOMSBURY WINTER 2022 JANUARY – APRIL BLOOMSBURY CHILDREN'S BOOKS • JANUARY 2022 JUVENILE FICTION / FAMILY / MULTIGENERATIONAL MARGARET CHIU GREANIAS Amah Faraway A delightful story of a child’s visit to a grandmother and home far away, and of how families connect and love across distance, language, and cultures. Kylie is nervous about visiting her grandmother—her Amah—who lives SO FAR AWAY. When she and Mama finally go to Taipei, Kylie is shy with Amah. Even though they have spent time together in video JANUARY chats, those aren’t the same as real life. And in Taiwan, Bloomsbury Children's Books Juvenile Fiction / Family / Multigenerational Kylie is at first uncomfortable with the less-familiar On Sale 1/25/2022 language, customs, culture, and food. However, after she is Ages 3 to 6 invited by Amah—Lái kàn kàn! Come see!—to play and Hardcover Picture Book 40 pages splash in the hot springs (which aren’t that different from 9.6 in H | 10.8 in W Carton Quantity: 12 the pools at home), Kylie begins to see this place through ISBN: 9781547607211 her grandmother’s eyes and sees a new side of the things $18.99 / $25.99 Can. that used to scare her. Soon, Kylie is leading her Amah—Come see! Lái kàn kàn!—back through all her favorite parts of this place and having SO MUCH FUN! And when it is time to go home, the video chats will be extra specia... Margaret Chiu Greanias is the author of Maximillian Villainous. The daughter of Taiwanese immigrants, she grew up in New York, Texas, and California, while her Amah lived faraway in Taipei. -

Awardsin ASSOCIATION WITH2021

WEST OF ENGLAND AwardsIN ASSOCIATION WITH2021 THE JUDGES’ NOMINATIONS 2021 TALENT SUPPORTED BY ON SCREEN TALENT Award for outstanding on-screen talent featured in a production • Presenter • Journalist • Show Host • Interviewer • Commentator • Cast Member Tom Kerridge Saving Britain’s Pubs with Tom Kerridge Megan McCubbin Springwatch 2020 Tala Gouveia McDonald & Dodds Nadiya Hussain Nadiya’s American Adventure PRODUCTION SCRIPTED SUPPORTED BY Award for best scripted content – for example serial or single drama, comedy, comedy-drama, one off special and returning series McDonald & Dodds Mammoth Screen The Spanish Princess Playground and New Pictures The Trial of Christine Keeler Ecosse Films The Cure Story Films Pale Horse Mammoth Screen THE JUDGES’ NOMINATIONS 2021 NATURAL HISTORY SUPPORTED BY Award for excellence in the production of Natural History Programme or Series Earth at Night in Colour Offspring Films Primates BBC Studios Natural History Unit Waterhole BBC Studios Natural History Unit Meerkat: A Dynasties Special BBC Studios Natural History Unit FACTUAL SUPPORTED BY Award for excellence in the production of Factual Programme/Content or Series including Popular and Specialist Factual • Science • Religion • History • Adventure • Arts Saving Britain’s Pubs with Tom Kerridge Bone Soup Productions Cornwall with Simon Reeve Beagle Media Nadiya’s American Adventure Wall to Wall West DOCUMENTARY SUPPORTED BY Award for excellence in the production of Documentary Programme/Content or Series Murder in the Car Park Indefinite Films Locked -

Original Television Soundtrack Composed by GEORGE FENTON

original television soundtrack composed by GEORGE FENTON VOLUME 1 FROM POLE TO POLE 01. Planet Earth Prelude 02. The Journey of the Sun 03. Hunting Dogs 04. Elephants in the Okavango CAVES 05. Diving into Darkness 06. Stalactite Gallery 07. Bat Hunt 08. Discovering Deer Cave FRESHWATER 09. Angel Falls 10. River Predation 11. Iguacu 12. The Snow Geese MOUNTAINS 13. The Geladas 14. The Snow Leopard 15. The Karakorum 16. The Earth’s Highest Challenge DESERTS 17. Desert Winds / The Locusts 18. Fly Catchers 19. Namibia - The Lions and the Oryx VOLUME 2 GREAT PLAINS 01. Plains High and Low 02. The Wolf and the Caribou 03. Tibet Reprise / Close SHALLOW SEAS 04. Surfing Dolphins 05. Dangerous Landing 06. Mother and Calf - The Great Journey JUNGLES 07. The Canopy / Flying Lemur 08. Frog Ballet / Jungle Falls 09. The Cordecyps 10. Hunting Chimps SEASONAL FORESTS 11. The Redwoods 12. Fledglings 13. Seasonal Change ICE WORLDS 14. Discovering Antarctica 15. The Humpbacks Bubblenet 16. Everything Leaves but the Emperors 17. The Disappearing Sea Ice 18. Lost in the Storm OCEAN DEEP 19. A School of Five Hundred 20. Giant Mantas 21. Life Near the Surface 22. The Choice is Ours Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne PLANET EARTH as you’ve never seen it before Impala, Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne Bears, Glacier National Park © DCI / Jean-Marc Giboux 01. Planet Earth Prelude 02. The Journey of the Sun 03. Hunting Dogs FROM POLE TO POLE 04. Elephants in the Okavango Wild dogs, Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne Polar bear and cub © Jason C Roberts Giraffes, Okavango © BBC Planet Earth / Ben Osborne Great white shark © Simon King 05. -

Listing Decisions Under the Endangered Species Act: Why Better Science Isn't Always Better Policy

Washington University Law Review Volume 75 Issue 3 January 1997 Listing Decisions Under the Endangered Species Act: Why Better Science Isn't Always Better Policy Holly Doremus University of California, Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Environmental Law Commons, Evidence Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Holly Doremus, Listing Decisions Under the Endangered Species Act: Why Better Science Isn't Always Better Policy, 75 WASH. U. L. Q. 1029 (1997). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol75/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Washington University Law Quarterly VOLUME 75 NUMBER 3 1997 ARTICLES LISTING DECISIONS UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT: WHY BETTER SCIENCE ISN'T ALWAYS BETTER POLICY HOLLY DOREMUS* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1031 II. DEVELOPMENT OF THE LEGISLATIVE SCIENCE MANDATE .................. 1037 A. Background................................................................................. 1037 1. Ambivalence Toward Science ............................................ 1037 2. The HistoricDominance ofScience -

Making Impossibly Smooth Motion a Reality

Motion Impossible Motion Impossible was instead spent pushing innovation in camera movement, working out how to set up sliders, ropes and pulleys, to move the camera through a scene, and he notes: Making “I like it when people go: ‘How the hell did you do that?’” One of his first proper credits was for a sequence showing a rock python giving impossibly birth. As this all happens underground, Rob built a set at a snake sanctuary in Uganda and lit it to match the location footage. Using a motorised slider and a miniature camera on an arm, he managed to film smooth the pythons coming down through the middle of a log with the camera right in front of them. motion a Moving to specialise in stabilisation When technology progressed still further with motors and stabilisers, Rob was first on the scene. Freefly brought their first MoVI reality prototypes to the BBC and Rob quickly took to the rig, using it to capture an array of MANTIS freestlye filming cheetah in Namibia amazing sequences for the series Wonders of the Monsoon. Rob explains: “When I was an underwater Having found his specialism of choice, Rob became cameraman I just loved the freedom of being able to move freelance and set himself up as ‘the MoVI man’. He would use the camera wherever I wanted to – but I ended up having bad it on sliders and zip lines and any way he could ears and couldn’t dive any more, so I really wanted to bring to get that stabilised camera head movement. -

Daily Listings Page: 1

Daily Listings Page: 1 LN - Sept 10 to 23 Printed by billw Channel: LOVE NATURE (On Air); Monday, September 10, 2018 to Sunday, September 23, 2018 September 10, 2018 1:21 pm D a t e P r e m i e r e T i t l e E p i s o d e C C D V I S A P Time On Monday, September 10, 2018 06:00 am A PARK FOR ALL SEASONS -- Grasslands 1 * 001 C C S A P 06:29 am A PARK FOR ALL SEASONS -- Point Pelee 1 * 002 C C 07:00 am ANIMAL SENSES -- Super Senses 1 * 5 C C 07:30 am ZOO JUNIORS -- Episode #7.7 7 * 07 C C 08:00 am A PARK FOR ALL SEASONS -- Grasslands 1 * 001 C C S A P 08:30 am A PARK FOR ALL SEASONS -- Point Pelee 1 * 002 C C 09:00 am ANIMAL SENSES -- Super Senses 1 * 5 C C 09:29 am ZOO JUNIORS -- Episode #7.7 7 * 07 C C 09:59 am GREAT BLUE WILD -- Giants Of Palau 2 * 3 C C 11:00 am GREAT BLUE WILD -- Indonesia - The Secret Life of Manta Rays 2 * 4 C C 12:00 pm GREAT BLUE WILD -- Indonesia - Amazon Of The Seas 2 * 5 C C 01:00 pm GREAT BLUE WILD -- Indonesia - Life In The Muck 2 * 6 C C 02:00 pm JUNGLE PLANET -- Jungles in the Sea: Canary Islands Laurel Forests 1 * 105 C C 02:30 pm JUNGLE PLANET -- Spectres of the Jungle: Madagascar Rainforest 1 * 106 C C 03:00 pm JUNGLE PLANET -- The Forests of Giants: California 1 * 107 C C 03:30 pm JUNGLE PLANET -- A World of Thorns: Thorny Forest, Madagascar 1 * 108 C C 04:00 pm LAND OF PRIMATES -- Lemurs of Anja Mountain 1 C C 05:00 pm GREAT PARKS OF AFRICA -- The Garden Route 2 * 1 C C 06:00 pm UNDISCOVERED VISTAS -- Iceland: Ice 2 * 2 C C 07:00 pm ANIMAL EMPIRES -- Family 1 * 1 C C 08:00 pm WILDEST EUROPE -- Forests And Woodlands 4 C C 08:51 pm WILDEST EUROPE -- Arid Lands 5 C C 09:43 pm WILDEST INDOCHINA -- Cambodia: The Water Kingdom 1 C C 10:35 pm WILD WILD EAST -- Horses of St. -

The Blue Planet

original television soundtrack THE BLUE PLANET composed by GEORGE FENTON Introduction “Our planet is a Blue Planet. The Deep ocean is by far the largest habitat on Earth... 60 per cent is covered by ocean more than a mile deep...” Alastair Fothergill - Series Producer For as long as music has been written, the sea has been a major source of inspiration for composers; but not one of them had my luck in being given the amazing images of The Blue Planet. Three years ago when I was asked to write the music, I imagined footage which would be awesome, terrifying and magnificent. It is all of these things, but my lasting impression and for me the greatest achievement is that the remarkable films Alastair Fothergill, Martha Holmes and Andy Byatt have made, actually manage to make the oceans feel as natural a habitat as the land. They have achieved this by a spectacular mix of scientific knowledge and dramatic flair. They love what they do and it shows. The same is true of David Attenborough. His commentaries are distinguished in their understanding, love of the subject and (luckily for me) their musicality. I owe so much to Dave Lawson whose musicianship, critical ear and persistent good humour contributed more than a credit could ever reflect. To Geoff Alexander, for his beautiful orchestrations and to Bill, Nicole, Steve, Tom, Bill Ives and the Choir and Ian Maclay and the Orchestra who all entered in to the spirit of this amazing series of films; and now thanks to Jane Carter and all at BBC Music - The Blue Planet is an album too. -

BBC 4 Listings for 1 – 7 July 2017 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 01 JULY 2017 the Early Punk Machinations of the 'Mock Rock' New York Mingei Pottery Dolls

BBC 4 Listings for 1 – 7 July 2017 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 01 JULY 2017 the early punk machinations of the 'mock rock' New York Mingei Pottery Dolls. Archive from the pinnacle year, 1973, features Roxy SAT 19:00 Britain and the Sea (b03lbv22) Music, The Wailers and Vinegar Joe. The programme's finale The final episode features one of Japan's most famous family of Trade and Romance celebrates the advent of punk and new wave with unforgettable potters - the Hamadas. Shoji Hamada was a major figure in the performances from Patti Smith, Blondie, Iggy Pop and The Mingei folk art movement of the 1920s and '30s and helped This third episode traces the crucial importance of the sea to Jam. turn the town of Mashiko into a major centre of ceramics, Britain's trade and to individual livelihoods of coastal famous for its thick and rustic pottery. He also spent time in communities. Joined on this leg of his epic sail by his son Fred, Artists featured are Elton John, Lindisfarne, David Bowie, Britain where he taught renowned St Ives potter Bernard Leach David follows the trade routes of the west coast of Scotland Curtis Mayfield, Gladys Knight & The Pips, Steppenwolf, the art of Japanese pottery. along the monumental channels that cut through the romantic Vinegar Joe, Brinsley Schwarz, New York Dolls, Argent, Bob Highlands and brought wealth and prosperity to the heart of Marley & The Wailers, Captain Beefheart, Johnny Winter, Dr Today, his grandson Tomoo Hamada continues the family Scotland. The journey starts at Craobh Haven and takes David Feelgood, Gil Scott Heron, Patti Smith, Tom Petty & The tradition and this film follows him at work, painstakingly along the Crinan Canal, around the Isle of Bute and up the Heartbreakers, Cher & Gregg Allman, Talking Heads, The Jam, shaping his pots and firing them in an old-style wood-fuelled River Clyde towards Glasgow. -

For More Information on Our Content: [email protected] | Blueantinternational.Com Table of Contents

blue ant media For more information on our content: [email protected] | blueantinternational.com Table of Contents FACTUAL ENTERTAINMENT 4 SPECIALIST FACTUAL 4272 HIGH IMPACT DOCUMENTARIES 13042 KIDS & FAMILY 18442 SCRIPTED 19642 CONTACTS 20042 FACTUAL ENTERTAINMENT Searching For Secrets Every great city has its secrets, you just have to know where to search for them…Scratch the surface of any city, and you’ll discover a secret history packed with fascinating stories, remarkable characters, and surprising twists. And more often than not, it’s right there in plain sight. If we only knew where to look. In SEARCHING FOR SECRETS, a cast of local guides, bloggers and historians, takes us on an extraordinary journey around some of the world’s most iconic cities…from the eerie catacombs of Paris, to the hustle and bustle of London’s west end. From New York’s iconic Statue of Liberty, to the grafiti covered remains of the Berlin Wall. With the help of intriguing clues and objects, we journey back in time to reveal the secret history of the cities we know and love, and shine new light on the exciting, and often surprising stories that helped shape them. 6 x 60’ 4K & HD TRAVEL, HISTORY Original Broadcaster: Smithsonian US & Smithsonian Canada Producer: Bigger Bang & Saloon Media 4 5 FACTUAL ENTERTAINMENT Deep Water World’s Most Scenic Salvage River Journeys While extreme weather continues to increase and disrupt There’s no better perspective than from a boat on a river, the shipping industry, it’s creating a boom for another one. as it gently winds its way through stunning landscapes Marine salvage crews are regularly called on to save the day and outstanding natural beauty. -

Curriculum Vitae

director of photography curriculum vitae career summary Director of Photography (3 x BAFTA nominated) working in factual documentary & natural history with extensive worldwide location experience. Strong background in lighting & specialist flming techniques including time-lapse, slow-motion & motion control. Experienced across formats for TV & IMAX including HD, 5k and 3D in live action & time-lapse. Designer and developer of motion-control equipment for stop-frame, live action & high speed. Degree in Biological Sciences with a passion for science communication. Previously a stills photographer for 10 years, and theatrical lighting designer / technician. Comfortable appearing and speaking on camera. about me Qualifications Skills & experience 3D Awards & achievements BSc (Hons) Biology (2:1) Director of photography Director of photography BAFTA Nomination (Cinematography): ing!om of "lants #Sc Business Time-lapse (& gra!ing) Stereography BAFTA Nomination (Special 'ffects): #icro #onsters NVQ (Film '!iting in FCP) #otion%control #acro BAFTA Nomination (Special 'ffects): Con*$est of the S+ies "AD, -penwater Stills photographer Time-lapse F$ll /oting mem0er of BAFTA iVisa (1SA) "hantom 2+ & 2+ 3ight weight rig !ev4mnt #em0er of BAFTA Cinematography 5$ry (Fiction) 2615 F$lly /accinated for tra/el VF8 9 Bl$e screen H$ge ,A :$r+ha exhi0ition with 5oanna 3$mley ,#A8 #$lti%layer compositing ,VCA Sil/er Awar! (Chilli Ba0y< Dir= '! #c:own) some key links Showreel: http:99...=ro0erthollingworth=co=$+9films9showreel9 "hone: >22 (6) ?@AB 111 @AC ,#D0: