Propaganda and Memory in Li Kunwu and Philippe Ôtié's a Chinese Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sinitic Language and Script in East Asia: Past and Present

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 264 December, 2016 Sinitic Language and Script in East Asia: Past and Present edited by Victor H. Mair Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Montrez-Moi La Chine ! Raymond Klein

woxx | 17 04 2015 | Nr 1315 REGARDS 11 KULTUR Les profs défilent devant leurs élèves. Assemblée d’autocritique pendant la Révolution culturelle. BANDE DESSINÉE Montrez-moi la Chine ! Raymond Klein Li Kunwu est un dessinateur chinois les journaux disent que des enfants Pendant quatre ans, ce sera la qui bave, et parfois comme tracés qui publie dans le « Quotidien du plus jeunes, âgés de six mois seule- « Grande famine », avec plusieurs d’une main tremblante. Dans cer- Yunnan » et… chez Dargaud. Il nous ment, y parviennent. Mais le petit Li dizaines de millions de morts. Le taines scènes les aplats noirs - nuit fait voir la société, la politique et échoue dès la première syllabe : au père de Li Kunwu, un communiste ou ombres - dominent les vignettes, l‘istoire à travers les yeux d’un lieu d’énoncer un « Mao zhuxi », il convaincu qui a fait la guerre civile, et les effets de texture pour simuler Chinois. ne bredouille que des « ma » et des est désormais « chef de bureau ». Il a des dégradés de gris ont un carac- « pa » confus. Et le père de conclure : tout vu venir, il désespère de la folie tère menaçant, comme une poussière Scène de rue dans le vieux centre « J’ai bien peur que ce ne soit pas politique, mais il doit continuer à faire maléfique qui envahit la vie des per- de Kunming, un joueur de viole une lumière. » « son travail ». Le récit de ces événe- sonnages. Cela rappelle le style des chinoise sous la pleine lune, voya- ments tragiques alterne moments de grands lithographes. -

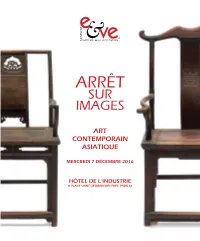

Arrêt Sur Images

ARRÊT SUR IMAGES ART CONTEMPORAIN ASIATIQUE MERCREDI 7 DÉCEMBRE 2016 HÔTEL DE L’INDUSTRIE 4, PLACE SAINT-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS, PARIS 6è ALAIN LEROY Commissaire - priseur habilité Titulaire d’un office de commissaire - priseur judiciaire #ARRÊT SUR IMAGES ART CONTEMPORAIN ASIATIQUE DONT COLLECTION BERTRAND CHEUVREUX AU PROFIT DE LA FDAC FONDATION POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT DE L’ART CONTEMPORAIN MERCREDI 7 DÉCEMBRE 2016 19H00 HÔTEL DE L'INDUSTRIE 4, PLACE SAINT-GERMAIN-DES-PRÉS 75006 PARIS EXPOSITION PUBLIQUE SAMEDI 3 DÉCEMBRE 2016 DE 11H À 19H DIMANCHE 4 DÉCEMBRE 2016 DE 11H À 19H LUNDI 5 DÉCEMBRE 2016 DE 11H À 19H MARDI 6 DÉCEMBRE 2016 DE 11H À 19H EVE AUCTION 9, rue Milton 75009 Paris Agrément n°2002-84 + 33 (0) 1 53 34 04 04 [email protected] www.auctioneve.com SUIVEZ-NOUS SUR FACEBOOK ET INSTAGRAM Pour tous renseignements : DELPHINE CHEUVREUX-MISSOFFE Commissaire-Priseur habilité T.+33 (0)1 53 34 04 04 [email protected] SAMUEL LANDÉE +33 (0)1 53 34 04 04 [email protected] PIA COPPER Expert en art contemporain asiatique T.+33 (0)6 89 33 63 16 [email protected] ARMELLE MAQUIN Presse et communication T. +33 (0)6 11 70 44 74 [email protected] L’intégralité du catalogue est visible sur notre site internet www.auctioneve.com Enchérissez en direct sur Crédits: Textes / Recherches: Pia Copper & Samuel Landée Photographies: Henri Du Cray Pages 6 et 7 : Hôtel de l’Industrie Pages 66 : courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio Design: Silvia Pacheco & Best Document LES PHOTOGRAPHIES DU CATALOGUE N’ONT PAS DE VALEUR CONTRACTUELLE EVE # ARRÊT SUR IMAGES ARRÊT SUR IMAGES.. -

Voyage En Chine - Guide Pratique Evaneos.Com

Chine La Grande Muraille de La beauté des paysages Les joies du palais dernité s et mo radition entre t ecture : L'archit Les minorité ethniques Voyage en Chine - Guide Pratique Evaneos.com Ensemble adoptons des gestes responsables : N'imprimez que si nécessaire. Merci. 1 Quand partir en Chine Quel est le meilleur Les évènements en Chine moment pour aller en Chine ? La Chine est un très grand L’événement le plus important du calendrier chinois est le Nouvel An chinois, basé pays, pas facile de sur le calendrier lunaire. Il se situe entre fin janvier et début février. Un bon moment savoir quelle est la pour voyager si on veut voir les animations et les feux d’artifice de cette fête majeure. meilleure période Le problème, c’est que tous les Chinois profitent de cette « semaine d’or » pour rentrer pour s’y rendre… dans leur Laojia ou province d’origine. Il peut-être difficile de se déplacer et de Alors nombreux établissements sont fermés à ce moment là. Il vous faudra contacter votre guide francophone bien en avance si vous partez à ce moment là. La fête nationale a lieu le 1 er octobre, c’est aussi la seconde semaine d’or. Attendez- vous à rencontrer les mêmes difficultés de réservation. La fête du travail a lieu le 1 er mai et les Chinois ont alors trois jours de congés, c’est la dernière période difficile pour se déplacer en Chine due aux masses de personnes qui voyagent à ce moment là. Pour en savoir plus, rendez-vous sur notre page fête en Chine Le climat en Chine La Chine est un immense pays avec des provinces très contrastées. -

REVUE DE PRESSE Chine - Mongolie 法国国家科学研究中心 Dépasser Les Frontières CNRS

REVUE DE PRESSE Chine - Mongolie 法国国家科学研究中心 dépasser les frontières CNRS Edition– SEPTEMBRE/OCTOBRE 2019 L’objectif de cette revue de presse est avant tout de balayer l'actualité telle qu’elle apparaît au Bureau du CNRS en Chine, mais aussi de poser un regard plus analytique sur les récents développements de la recherche en Chine. L’accent est certes mis sur le continuum formation-recherche-innovation, mais la revue entend aussi laisser de la place à ce qui entoure la science, à 1er Oct. - Célébrations du 70e anniversaire de la RPC l’image du CNRS qui embrasse tous les champs de la connaissance. er Dans l’éditorial de notre revue couvrant les mois de sept/octobre, un mot La Chine , 1 partenaire scientifique d’arrivée du nouveau directeur du bureau du CNRS en Chine. du CNRS en Asie Coopère depuis 1978 avec la Chine Le point de départ de cette revue est également de faire en sorte que 71 % des copublications France-Chine chaque lecteur puisse construire son point de vue alors que le système Actions structurantes : d’information en Chine demeure très contrôlé. Rappelons-le également, 21 LIA, 5 IRN (ex GDRI), 1 UMI, l'accès aux informations constitue également un défi en Chine, barrière de 1 UMIFRE, 3 plateformes la langue oblige. 1 491 doctorants chinois et 134 Postdocs Bonne lecture ! dans les unités du CNRS (2018) 1 487 missions vers la Chine (2018) Les publications CNRS Chine Sommaire Editorial : Philippe Arnaud, nouveau directeur du bureau du CNRS en Chine Economie, politique et société Education, science, technologie et innovation -

A Chinese Life Free

FREE A CHINESE LIFE PDF Li Kunwa,Phillipe Otie | 720 pages | 01 Sep 2012 | Selfmadehero | 9781906838553 | English | London, United Kingdom Comic book review: A Chinese Life (从小李到老李) | Marta lives in China This distinctively drawn work chronicles the rise and reign of Chairman Mao Zedong, and his sweeping, often cataclysmic vision for the most populated country on the planet. Li Kunwu spent more than 30 years as a state artist for the Communist Party. He saw firsthand what was happening to his family, his neighbors, and his homeland during this extraordinary time. The site includes thousands of articles on this country structured in categories: news, trends, economy, history, A Chinese Life, guides, literaturepictures gallery, videos and Chinese cinema. View previous campaigns. We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed. Agree You can unsubscribe at any time by A Chinese Life the A Chinese Life in the footer of our emails. Comics Art in China Next. We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it. Ok No Privacy policy. You can revoke your A Chinese Life any time using the Revoke consent button. Revoke cookies. A Chinese Life by Li Kunwu Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. -

Transparence Et Contrôle Des Marges En Chine : Une Histoire Politique Du Yunnan

UNIVERSITÉ DE LYON Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Lyon et Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon Transparence et contrôle des marges en Chine : une histoire politique du Yunnan (1992-2016). Thibaut BARA Master Asie Orientale Contemporaine : parcours études 2018/2019 Sous la direction de Stéphane CORCUFF, maître de conférences à Sciences Po Lyon et chercheur associé au Centre d’Etudes Français sur la Chine contemporaine. Avec comme membre du jury, Jean-Louis MARIE, professeur de sciences politiques à Sciences Po Lyon. 1 2 Déclaration anti-plagiat 1. Je déclare que ce travail ne peut être suspecté de plagiat. Il constitue l’aboutissement d’un travail personnel. 2. A ce titre, les citations sont identifiables (utilisation des guillemets lorsque la pensée d’un auteur autre que moi est reprise de manière littérale). 3. L’ensemble des sources (écrits, images) qui ont alimenté ma réflexion sont clairement référencées selon les règles bibliographiques préconisées. NOM : BARA PRENOM : Thibaut DATE : le 3 septembre 2019 3 Transparence et contrôle des marges en Chine : une histoire politique du Yunnan. (1992-2016) 4 Sommaire Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 10 Contextualisation ................................................................................................................... 10 Problématisation .................................................................................................................... 13 Enjeux et Intérêt -

A CHINESE LIFE Li, K., & Otie, P

A CHINESE LIFE Li, K., & Otie, P. (2012). A Chinese life. (E. Gauvin, Trans.). London, United Kingdom: SelfMadeHero. Publisher’s Page: http://www.selfmadehero.com/title.php?isbn=97 81906838553&edition_id=210 Amazon’s Page: http://www.amazon.com/A-Chinese-Life-Philippe- Otie/dp/B00BZCA3UO/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1 369735412&sr=8-1&keywords=A+Chinese+Life GoodReads Reviews: http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/13588689- a-chinese-life HDFS 892 ~ Tara Popp ~ Michigan State University Book Background This is a graphic novel-memoir of Li Kunwu, a Chinese man from Yunnan Province. He and a French diplomat and writer, Philippe Otie, teamed up to create this book that spans five decades of Li’s life. This memoir was originally published in French. The book is divided into three parts. Book I: The Time of the Father The first book starts in 1950, with the meeting of Li’s parents in Yunnan province. Li’s father is 25, and Li’s mother is 17. Li himself was born in 1955, and he and his little sister are raised in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan. As they were growing up, they were taught to revere Mao Zedong. In 1958, the Great Leap Forward campaign began, and readers see through Li’s eyes of how his countrymen turned their homes into barren wasteland as they did a “backyard Industrial Revolution” to catch up with the British and the Americans. Schoolchildren even contributed to this revolution by killing mosquitoes, catching rats, and scaring off birds out of their crops. Not only were their lands getting damaged, but folklores and customs of old China were becoming forbidden as the Chinese tried to become “modern”. -

Graphic Novels and Picture Books

A.B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson Library Graphic Novels and Picture Books Graphic Novels Aaron, Jason Scalped : Indian Country GRA AAR Fifteen years ago, Dashiell Bad Horse ran away from a life of abject poverty and utter hopelessness on the Prairie Rose Indian Reservation in hopes of finding something better. Now he's come back home armed with nothing but a set of nunchucks, a hell-bent-for-leather attitude and one dark secret, to find nothing much has changed on The Rez - short of a glimmering new casino, and a once-proud people overcome by drugs and organized crime. Is he here to set things right or just get a piece of the action? Aaron, Jason Amazing X-Men : the Quest for Nightcrawler GRA AAR Ever since Nightcrawler's death, the X-Men have been without their heart and soul. But after learning that their friend may not be gone after all, it's up to Wolverine, Storm, Beast, Iceman, Northstar and Firestar to find and bring back the fuzzy blue elf! Ahmed, Safdar (ed.) Refugee Art Project Zine 1 GRA REF Art work by refugees in the Villawood Detention Centre. Most of the comics in this zine were made by Hazara refugees from Afghanistan, who are one of the largest groups in Australia's detention system. Ahmed, Safdar (ed.) Refugee Art Project Zine 2: The Cartoons of GRA REF Mohammad Art work by refugees in the Villawood Detention Centre. Much of this zine is devoted to the Rohingya people of Burma - a persecuted religious and ethnic minority who are considered by the Burmese government to be non-citizens. -

Yishu 54.Pdf

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2013 VOLUME 12, N UMBER 1 INSI DE Third Yishu Awards for Critical Writing on Contemporary Chinese Art Artist Features: Chen Chieh-jen, Chen Zhen, Wang Qingsong, Han Feng Curatorial Inquiries 12 The Art of Archiving Exhibitions in Istanbul and London Li Kunwu: A Chinese Life US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 16 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1, JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2013 CONTENTS Editor’s Note 29 Contributors 6 Third Yishu Awards for Critical Writing on Contemporary Chinese Art 9 The Context of Contemporary Chinese Art in the New Century Lü Peng 16 Unauthorized Archive: Profane Illumination in 42 Chen Chieh-jen’s Works Chou Yu-ling 29 Transexperiencing Chen Zhen’s Art Amjad Majid 42 Wang Qingsong’s Use of Buddhist Imagery (There Must Be a Buddha in a Place Like This) Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky 55 The “Being and Nothingness” of Han Feng Voon Pow Bartlett 55 66 Curatorial Inquiries 12 Nikita Yingqian Cai and Carol Yinghua Lu 71 The Art of Archiving: A Conversation with Karen Smith Elizabeth Parke 83 On Form and Flux: Change and Transformation in Chinese Art at the Istanbul Modern and the Hayward Gallery, London 71 Stephanie Bailey 95 Li Kunwu: A Chinese Life Ryan Holmberg 106 Chinese Name Index Cover: Chen Zhen at Le Magasin, Centre national d'art 95 contemporain, Grenoble, France, 1992. Photo: Xu Min. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Canadian Foundation of Asian Art, Ping Chen, Mr. and Mrs. Eric Li, and Stephanie Holmquist and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. -

Une Espérance Pour Notre Temps : Le Foisonnement De L'interculturel Et De

Le Langage et l’Homme, vol. XLIX, n° 2 (décembre 2014) Une espérance pour notre temps : Le foisonnement de l’interculturel et de l’interreligieux Chine – Occident (aire francophone) Pierre YERLES Professeur émerite de l’Université catholique de Louvain Il n’y a guère si longtemps qu’il était de rigueur ou de mise de se méfier voire de se gausser, et à juste titre, des diverses formes occidentales d’assemblage syncrétique interculturel et interreligieux effectuées sur base de matériaux asiatiques, dont la vogue du « New Age » fut, quelques décennies durant, l’illustration la plus voyante. Et il est vrai que, quand bien même cette vogue du « New Age » en disait long sur la dévaluation du discours culturel ou religieux occidental traditionnel, elle s’accompagnait de tant de dérives marchandes ou d’appropriations caricaturales des matériaux dont elle s’enorgueillissait, qu’il y avait bien lieu de tenir en suspicion ce bric-à-brac de religiosité ou de sous-culture postmoderne. Je voudrais soutenir ici, en relevant et examinant pour l’essentiel des liens plus récents, établis depuis notre ancrage de culture francophone, avec les cultures ou les religions chinoises , que le temps est venu de se réjouir de ce qui apparaît désormais comme un véritable foisonnement de l’interculturel et de l’interreligieux Occident-Chine. Entraîné par le phénomène de la mondialisation et le rééquilibrage progressif des rapports de force entre l’ancien empire du Milieu et ses anciens colonisateurs, favorisé par toutes les métamorphoses du monde contemporain et, entre autres, les révolutions éditoriales et médiatiques, ce nouveau dialogue interculturel ne fait l’impasse ni sur les différences, ni sur les ressemblances, évite les écueils de cet exotisme dont Segalen se méfiait si légitimement, s’inscrit dans une perspective autant historique ou fonctionnaliste qu’essentialiste et témoigne d’un nouveau régime de questionnement et de partage dans lequel il est légitime de voir une espérance pour notre temps. -

Laetitia Rapuzzi Relations Franco-Chinoises Dans La Bande

Laetitia Rapuzzi Relations Franco-Chinoises dans la bande dessinée de 1900 à 2016 : intertextualités et représentations de la Chine -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- RAPUZZI Laetitia. Relations Franco-Chinoises dans la bande dessinée de 1900 à 2016 : intertextualités et représentations de la Chine, sous la direction de Florent Villard. - Lyon : Université Jean Moulin (Lyon 3), 2016. Mémoire soutenu le 29/06/2016. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Document diffusé sous le contrat Creative Commons « Paternité – pas d’utilisation commerciale - pas de modification » : vous êtes libre de le reproduire, de le distribuer et de le communiquer au public à condition d’en mentionner le nom de l’auteur et de ne pas le modifier, le transformer, l’adapter ni l’utiliser à des fins commerciales. Université Jean Moulin Lyon III Mémoire de Master Recherche Langues et Cultures Étrangères Études Chinoises RELATIONS FRANCO-CHINOISES DANS LA BANDE DESSINÉE DE 1900 À 2016 : INTERTEXTUALITÉS ET REPRÉSENTATIONS DE LA CHINE Soutenu par Laetitia Rapuzzi Sous la direction de Monsieur le professeur Florent Villard Année Universitaire 2015 - 2016 Université Jean Moulin Lyon III Mémoire de Master Recherche Langues et Cultures Étrangères Études Chinoises RELATIONS FRANCO-CHINOISES DANS LA BANDE DESSINÉE DE 1900 À 2016 : INTERTEXTUALITÉS ET REPRÉSENTATIONS DE LA CHINE Soutenu par Laetitia Rapuzzi Sous la direction de Monsieur le professeur Florent Villard Année Universitaire 2015 - 2016 Remerciements Le travail qui m’est donné de présenter aujourd’hui n’aurait jamais pu être réalisé sans la confiance et le soutien de l’ensemble des professeurs du département de chinois de l’université Jean Moulin Lyon 3. Il me paraît nécessaire de les remercier ainsi que tous ceux qui m’auront, d’une manière ou d’une autre, aidé à parcourir ce chemin.