UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

Bill 'Bojangles'

‘It’s all the way you look at it, you know’: reading Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson’s film career Author: Hannah Durkin Affiliation: University of Nottingham, UK This article engages with a major paradox in African American tap dancer Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson’s film image – namely, its concurrent adherences to and contestations of dehumanising racial iconography – to reveal the complex and often ambivalent ways in which identity is staged and enacted. Although Robinson is often understood as an embodiment of popular cultural imagery historically designed to dehumanise African Americans, this paper shows that Robinson’s artistry displaces these readings by providing viewing pleasure for black, as much as white, audiences. Robinson’s racially segregated scenes in Dixiana (1930) and Hooray for Love (1935) illuminate classical Hollywood’s racial codes, whilst also showing how his inclusion within these otherwise all-white films provides grounding for creative and self-reflexive artistry. The films’ references to Robinson’s stage image and artistry overlap with minstrelsy-derived constructions of ‘blackness’, with the effect that they heighten possible interpretations of his cinematic persona by evading representational conclusion. Ultimately, Robinson’s films should be read as sites of representational struggle that help to uncover the slipperiness of performances of African American identities in 1930s Hollywood. Keywords: Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson; tap dance; minstrelsy; specialty number; classical Hollywood Hannah Durkin. Email: [email protected] In 1935 musical Hooray for Love, a character played by Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson (1878-1949), one of Hollywood’s first black screen stars, declares, ‘it’s all the way you look at it, you know’ to describe his surroundings. -

The Key Reporter

reporter volume xxxi number four summer 1966 NEW PROGRAMS FOR THE HUMANITIES The National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities aspects of the program. Panels for review of proposals are celebrates its first birthday next month. One of the youngest also set up in selected fields. The Councils are obliged to make federal agencies, the Foundation was established last year by annual reports to the President for transmittal to Congress. the 89th Congress on September 16. Although legislation in Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities support of cultural undertakings, particularly the arts, had been before Congress for some 88 years, last year was the first In order to avoid duplication of programs and with an eye to time that legislation had been introduced to benefit both the assuring maximum opportunity for cooperative activities humanities and the arts means of one independent national by the among federal government agencies, a Federal Council on foundation. That Congress voted to enact this legislative pro Arts and the Humanities was also established by Congress. gram the first time it was introduced can be attributed to strong There are nine members on the Federal Council, including the Administration backing of the proposed Foundation, biparti Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, who serves as chair san support and sponsorship of the legislation in Congress, man. The Federal Council is authorized to assist in co and general public recognition and agreement that the national ordinating programs between the two Endowments and with government should support and encourage the humanities and related Federal bureaus and agencies; to plan and coordinate the arts. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

Sammy Davis Jr.'S Facts on Tap Dancing | Entertainment Guide

FIND LOCAL: Entertainment Guide Parties & Celebrations | Travel & Attractions | Sports & Recreation | Leisure Activities Entertainment Guide » Arts & Entertainment » Dance » Dancing » Sammy Davis Jr.'s Facts on Tap Dancing Sammy Davis Jr.'s Facts on Tap Dancing ADS BY GOOGLE by Sue McCarty, Demand Media In May 1990, the Las Vegas Strip went dark for 10 minutes to honor one of America's premier entertainers, Sammy Davis Jr. Davis began his professional life on a vaudeville stage tap dancing at the age of 3 and spent the next 61 years singing, dancing, impersonating and acting for an often racially prejudiced public. Tutored in tap by his father, Sammy Sr., and partner, Will Mastin, and advised by the immortal Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Davis spent his entire life on stages, in films and on television. Fred Astaire once said of Davis, "Just to watch him walk on stage was worth the price of admission." Learning the Craft Davis referred to his tap dancing skills as “a hand-me-down art form" because he was never formally trained in any aspect of dance. He learned by watching and imitating his father, Mastin and other professionals he came in contact with every night on vaudeville stages across the country. According to Davis, he remembered everything he saw, including timing, audience reaction to certain moves and how to direct the mood of the audience with facial expressions and gestures. RELATED ARTICLES Developing a Style Interesting Facts About Irish Step At the age of 10 Davis first saw Bill "Bojangles" Robinson on stage in Dancing Boston, which changed Davis' whole approach to tap dancing. -

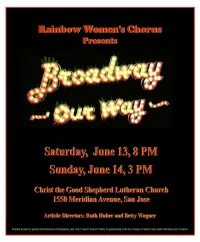

Broadway-Our-Way-2015.Pdf

Our Mission Rainbow Women’s Chorus works together to develop musical excellence in an atmosphere of mutual support and respect. We perform publicly for the entertainment, education and cultural enrichment of our audiences and community. We sing to enhance the esteem of all women, to celebrate diversity, to promote peace and freedom, and to touch people’s hearts and lives. Our Story Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a nonprofit corporation governed by the Action Circle, a group of women dedicated to realizing the organization’s mission. Chorus members began singing together in 1996, presenting concerts in venues such as Christ the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Le Petit Trianon Theatre, the San Jose Repertory Theater and Triton Museum. The chorus also performs at church services, diversity celebrations, awards ceremonies, community meetings and private events. Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a member of the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA). In 2000, RWC proudly co-hosted GALA Festival in San Jose, with the Silicon Valley Gay Men’s Chorus. Since then, RWC has participated in GALA Festivals in Montreal (2004), Miami (2008), and Denver (2012). In February 2006, members of RWC sang at Carnegie Hall in NYC with a dozen other choruses for a breast cancer and HIV benefit. In July 2010, RWC traveled to Chicago for the Sister Singers Women’s Choral Festival. But we like it best when we are here at home, singing for you! Support the Arts Rainbow Women’s Chorus and other arts organizations receive much valued support from Silicon Valley Creates, not only in grants, but also in training, guidance, marketing, fundraising, and more. -

Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Feminist Scholarship Review Women and Gender Resource Action Center Spring 1998 Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance Katharine Power Trinity College Joshua Karter Trinity College Patricia Bunker Trinity College Susan Erickson Trinity College Marjorie Smith Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Power, Katharine; Karter, Joshua; Bunker, Patricia; Erickson, Susan; and Smith, Marjorie, "Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance" (1998). Feminist Scholarship Review. 10. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview/10 Peminist Scfiofarsliip CR§view Women in rrlieater ana(])ance Hartford, CT, Spring 1998 Peminist ScfioCarsfiip CJ?.§view Creator: Deborah Rose O'Neal Visiting Lecturer in the Writing Center Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut Editor: Kimberly Niadna Class of2000 Contributers: Katharine Power, Senior Lecturer ofTheater and Dance Joshua Kaner, Associate Professor of Theater and Dance Patricia Bunker, Reference Librarian Susan Erickson, Assistant to the Music and Media Services Librarian Marjorie Smith, Class of2000 Peminist Scfzo{a:rsnip 9.?eview is a project of the Trinity College Women's Center. For more information, call 1-860-297-2408 rr'a6fe of Contents Le.t ter Prom. the Editor . .. .. .... .. .... ....... pg. 1 Women Performing Women: The Body as Text ••.•....••..••••• 2 by Katharine Powe.r Only Trying to Move One Step Forward • •.•••.• • • ••• .• .• • ••• 5 by Marjorie Smith Approaches to the Gender Gap in Russian Theater .••••••••• 8 by Joshua Karter A Bibliography on Women in Theater and Dance ••••••••.••• 12 by Patricia Bunker Women in Dance: A Selected Videography .••• .•... -

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection The Rudy Vallee collection contains almost 30.000 pieces of sheet music (about two thirds published and the rest manuscripts); about half of the titles are accessible through a database and we are presenting here the first ca. 2000 with full information. Song: 21 Guns for Susie (Boom! Boom! Boom!) Year: 1934 Composer: Myers, Richard Lyricist: Silverman, Al; Leslie, Bob; Leslie, Ken Arranger: Mason, Jack Song: 33rd Division March Year: 1928 Composer: Mader, Carl Song: About a Quarter to Nine From: Go into Your Dance (movie) Year: 1935 Composer: Warren, Harry Lyricist: Dubin, Al Arranger: Weirick, Paul Song: Ace of Clubs, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Diamonds, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Spades, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred K. Song: Actions (speak louder than words) Year: 1931 Composer: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Lyricist: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Arranger: Prince, Graham Song: Adios Year: 1931 Composer: Madriguera, Enric Lyricist: Woods, Eddie; Madriguera, Enric(Spanish translation) Arranger: Raph, Teddy Song: Adorable From: Adorable (movie) Year: 1933 Composer: Whiting, Richard A. Lyricist: Marion, George, Jr. Arranger: Mason, Jack; Rochette, J. (vocal trio) Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) Year: 1931 Composer: Lecuona, Ernesto Lyricist: Gilbert, L. Wolfe Arranger: Katzman, Louis Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Recordings are on vinyl unless marked otherwise marked (* = Cassette or # = Compact Disc) KEY OC - Original Cast TV - Television Soundtrack OBC - Original Broadway Cast ST - Film Soundtrack OLC - Original London Cast SC - Studio Cast RC - Revival Cast ## 2 (OC) 3 GUYS NAKED FROM THE WAIST DOWN (OC) 4 TO THE BAR 13 DAUGHTERS 20'S AND ALL THAT JAZZ, THE 40 YEARS ON (OC) 42ND STREET (OC) 70, GIRLS, 70 (OC) 81 PROOF 110 IN THE SHADE (OC) 1776 (OC) A A5678 - A MUSICAL FABLE ABSENT-MINDED DRAGON, THE ACE OF CLUBS (SEE NOEL COWARD) ACROSS AMERICA ACT, THE (OC) ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, THE ADVENTURES OF COLORED MAN ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO (TV) AFTER THE BALL (OLC) AIDA AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' (OC) AIN'T SUPPOSED TO DIE A NATURAL DEATH ALADD/THE DRAGON (BAG-A-TALE) Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection ALADDIN (OLC) ALADDIN (OC Wilson) ALI BABBA & THE FORTY THIEVES ALICE IN WONDERLAND (JANE POWELL) ALICE IN WONDERLAND (ANN STEPHENS) ALIVE AND WELL (EARL ROBINSON) ALLADIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP ALL ABOUT LIFE ALL AMERICAN (OC) ALL FACES WEST (10") THE ALL NIGHT STRUT! ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (TV) ALL IN LOVE (OC) ALLEGRO (0C) THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN AMBASSADOR AMERICAN HEROES AN AMERICAN POEM AMERICANS OR LAST TANGO IN HUAHUATENANGO .....................(SF MIME TROUPE) (See FACTWINO) AMY THE ANASTASIA AFFAIRE (CD) AND SO TO BED (SEE VIVIAN ELLIS) AND THE WORLD GOES 'ROUND (CD) AND THEN WE WROTE... (FLANDERS & SWANN) AMERICAN -

External Content.Pdf

i THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy is Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of English, Emeritus at the University of Connecticut. Among her 18 books on American drama and theatre are Tennessee Williams and Elia Kazan: A Collaboration in the Theatre (1992), Understanding David Mamet (2011), Congressional Theatre: Dramatizing McCarthyism on Stage, Film, and Television (1999), The Provincetown Players and the Culture of Modernity (2005), and as editor, Critical Insights: Tennessee Williams (2011) and Critical Insights: A Streetcar Named Desire (2010). In the same series from Bloomsbury Methuen Drama: THE PLAYS OF SAMUEL BECKETT by Katherine Weiss THE THEATRE OF MARTIN CRIMP (SECOND EDITION) by Aleks Sierz THE THEATRE OF BRIAN FRIEL by Christopher Murray THE THEATRE OF DAVID GREIG by Clare Wallace THE THEATRE AND FILMS OF MARTIN MCDONAGH by Patrick Lonergan MODERN ASIAN THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE 1900–2000 Kevin J. Wetmore and Siyuan Liu THE THEATRE OF SEAN O’CASEY by James Moran THE THEATRE OF HAROLD PINTER by Mark Taylor-Batty THE THEATRE OF TIMBERLAKE WERTENBAKER by Sophie Bush Forthcoming: THE THEATRE OF CARYL CHURCHILL by R. Darren Gobert THE THEATRE OF TENNESSEE WILLIAMS Brenda Murphy Series Editors: Patrick Lonergan and Erin Hurley LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Methuen Drama An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 © Brenda Murphy, 2014 This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher.