How Music Moved: the Genesis of Genres in Urban Centers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

2017 US OPEN Rules

US Open Swing Dance Championships/Rules & Competitions/2017v-1 2017 US OPEN Rules MISSION STATEMENT Our mission is to provide the best possible environment to showcase the highest level of competition from around the world, and thus provide the most exciting entertainment for our attendees. GENERAL RULES & INFORMATION STATEMENT OF SWING This statement of Swing is to be used to identify the presence of swing in the Swing Divisions at the US Open Swing Dance Championships. Swing is an American Rhythm Dance based on a foundation of 6-beat and 8-beat patterns that incorporate a wide variety of rhythms built on 2-beat single, delayed, double, triple, and blank rhythm units. The 6-beat patterns include, but are not limited to, passes, underarm turns, push-breaks, open-to-closed, and closed-to-open position patterns. The 8-beat patterns include, but are not limited to, whips, swing-outs, Lindy circles, and Shag pivots. Although they are not part of the foundation of the dance as stated above, 2- beat and 4-beat extension rhythm breaks may be incorporated to extend a pattern, to phrase the music, and/or to accent breaks. (For additional information, please visit http://www.nasde.net/rules.php) The objective is to provide a competitive performance venue for the various unique styles of swing that have developed across the nation to include the Carolina Shag, Dallas Push, East Coast Swing, Hand Dancing, Hollywood Swing, Houston Whip, Imperial Swing, Jive, Jitterbug, Lindy Hop, Rock-n-Roll, and West Coast Swing, to name a few. The US Open Swing Dance Championships divisions are open to a variety of Swing dances, except in Cabaret division. -

By Barb Berggoetz Photography by Shannon Zahnle

Mary Hoedeman Caniaris and Tom Slater swing dance at a Panache Dance showcase. Photo by Annalese Poorman dAN e ero aNCE BY Barb Berggoetz PHOTOGRAPHY BY Shannon Zahnle The verve and exhilaration of dance attracts the fear of putting yourself out there, says people of all ages, as does the sense of Barbara Leininger, owner of Bloomington’s community, the sheer pleasure of moving to Arthur Murray Dance Studio. “That very first music, and the physical closeness. In the step of coming into the studio is sometimes a process, people learn more about themselves, frightening thing.” break down inhibitions, stimulate their Leininger has witnessed what learning to minds, and find new friends. dance can do for a bashful teenager; for a man This is what dance in Bloomington is who thinks he has two left feet; for empty all about. nesters searching for a new adventure. It is not about becoming Ginger Rogers or “It can change relationships,” she says. “It Fred Astaire. can help people overcome shyness and give “It’s getting out and enjoying dancing and people a new lease on life. People get healthier having a good time,” says Thuy Bogart, who physically, mentally, and emotionally. And teaches Argentine tango. “That’s so much they have a skill they can go out and have fun more important for us.” with and use for the rest of their lives.” The benefits of dancing on an individual level can be life altering — if you can get past 100 Bloom | April/May 2015 | magbloom.com magbloom.com | April/May 2015 | Bloom 101 Ballroom dancing “It’s really important to keep busy and keep the gears going,” says Meredith. -

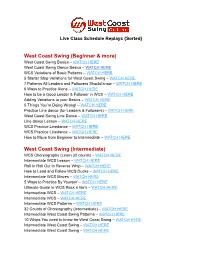

West Coast Swing (Beginner & More)

Live Class Schedule Replays {Sorted} West Coast Swing (Beginner & more) West Coast Swing Basics – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Dance Basics – W ATCH HERE WCS Variations of Basic Patterns – W ATCH HERE 5 Starter Step Variations for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE 7 Patterns All Leaders and Followers Should know – W ATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice Alone – WATCH HERE How to be a Good Leader & Follower in WCS – WATCH HERE Adding Variations to your Basics – W ATCH HERE 5 Things You’re Doing Wrong! – WATCH HERE Practice Line dance (for Leaders & Followers) – W ATCH HERE West Coast Swing Line Dance – WATCH HERE Line dance Lesson – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE WCS Practice Linedance – W ATCH HERE How to Move from Beginner to Intermediate – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing (Intermediate) WCS Choreography (Learn 32 counts) – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Lesson – WATCH HERE Roll In Roll Out to Reverse Whip – WATCH HERE How to Lead and Follow WCS Ducks – W ATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Moves – WATCH HERE 5 Ways to Practice By Yourself – WATCH HERE Ultimate Guide to WCS Rock n Go’s – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS – WATCH HERE Intermediate WCS Patterns – WATCH HERE 32 Counts of Choreography (Intermediate) – W ATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing Patterns – WATCH HERE 10 Whips You need to know for West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE Intermediate West Coast Swing – WATCH HERE West Coast Swing ( Advanced) Advanced WCS Moves – WATCH HERE -

An Improvised World: Jazz and Community in Milwaukee, 1950-1970 Benjamin Barbera University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2012 An Improvised World: Jazz and Community in Milwaukee, 1950-1970 Benjamin Barbera University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, History Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Barbera, Benjamin, "An Improvised World: Jazz and Community in Milwaukee, 1950-1970" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 5. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN IMPROVISED WORLD: JAZZ AND COMMUNITY IN MILWAUKEE, 1950 – 1970 by Benjamin A. Barbera A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August 2012 ABSTRACT AN IMPROVISED WORLD: JAZZ AND COMMUNITY IN MILWAUKEE, 1950 – 1970 by Benjamin A. Barbera The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2012 Under the Supervision of Professor Robert Smith This study looks at the history of jazz in Milwaukee between 1950 and 1970. During this period Milwaukee experienced a series of shifts that included a large migration of African Americans, urban renewal and expressway projects, and the early stages of deindustrialization. These changes had an impact on the jazz musicians, audience, and venues in Milwaukee such that the history of jazz during this period reflects the social, economic, and physical landscape of the city in transition. -

FEET FIRST:An Invitation to Dance

QPAC PRESENTS FEET FIRST: an invitation to dance Dance Genres Learn more about each of the genres and presenters on show at Feet First. This culture represents a living heritage left by the African slaves in Brazil, in which context Capoeira and Afro-Brazilian dances constitute a whole. For this reason, the pratice of Capoeira Afro-Brazilian always comes together with Afro-Brazilian dances such as Maculelê, Samba de Roda and Puxada de Rede. Presented by: http://www.xangocapoeira.com.au/ Creative movement and dance for 3-8 year olds. Designed specifi cally for young children, baby ballet introduces the foundations of dance through movement, rhythm, imagination and Baby Ballet creative play. Presented by: http://www.brisbanedancetheatre.com.au/tipoe-dance/ Ballet is a type of performance dance that originated in the Italian Renaissance courts of the 15th century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since Ballet become a widespread, highly technical form of dance with its own vocabulary. Presented by: http://www.vaganova.com.au/classes/http://www.2ballerinas.com/ Ballroom dance is a set of partner dances, which are enjoyed both socially and competitively around the world. Because of its performance and entertainment aspects, ballroom dance is also widely enjoyed on stage, fi lm, and television. Ballroom dance may refer, at its widest, to almost any type of social dancing as recreation. Ballroom Dance However, with the emergence of dancesport in modern times, the term has become narrower in scope. It usually refers to the International Standard and International Latin style dances. -

Chicago Summerdance Brochure 2019

SUMMERDANCE FREE DOWNS NCING DA & IN THE PARKS C L SI IVE MU CHICAGO Saturday, July 27 Saturday, August 17 2-5pm 2-5pm Hamilton Park Austin Town Cultural Center Hall Park SUMMER 513 W. 72nd St. 5610 W. Lake St. DANCE SummerDance Downs in the Park return to Chicago Park District locations this summer! co-presented with Open the Circle CELEBRATION Dance downs showcase black youth dance groups from across Saturday, August 24 | 1 - 8pm the city. Today's dance groups are famous for their performances at the Bud Billiken Parade and other parades A full day of free social dancing and across the city and beyond. Several groups travel nationally to perform, winning awards and recognition from television performances throughout Millennium Park programs like Bring It!, while instilling community, leadership Highlights include: and self-confidence in Chicago youth. Dance Downs in the Wrigley Square Dance Village Park are organized in partnership with leading companies The hosted by See Chicago Dance Era Footwork Crew, Empiire and Bringing Out Talent. Music is highlighting Chicago’s diverse dance performance companies, provided by "the youngest in charge" DJ Corey and his father schools, artists and advocacy groups DJ Clent, godfather of footwork music and juke in Chicago. Dance Workshops and fun for all on the Great Lawn and Cloud Gate Plaza Professional dance performances at the Jay Pritzker Pavilion featuring HubbardTheatre, Street Joel Dance Hall Dancers Chicago, and Cerqua more! Rivera Dance Most SummerDance events start with an introductory, one-hour dance lesson by professional instructors followed by live music and dancing. -

Swing Day 1 Lesson Plan Outline Introduction to Basic Dance & Swing

SWING DAY 1 LESSON PLAN OUTLINE INTRODUCTION TO BASIC DANCE & SWING OVERVIEW Lesson one focuses on an introduction to basic dance skills. The goal is to get students dancing in rhythm; first with a dance they can do individually, and then with basic swing dance steps they do in coordination with a partner. LEARNING OUTCOME Student will be able to: 6. Dance the basic steps to a line dance and coordinate their movements together as a group. 7. Ask permission and show respect to a dance partner. 8. Dance the East Coast Swing basic step in an open dance position with a partner. 9. Understand how to establish and maintain personal space when dancing as an individual in a group, and when dancing with a partner. 10. Understand how to show appreciation to their partner at the end of a song, and why it is important. ACTIVITY Warm Up 1. Teach the Line dance: Stop the Bus Lesson Focus 1. Teach the basic East Coast Swing step 2. Understand the basic footwork and the distinct timing 3. Teach how to ask permission and create connection 4. Teach why we applaud at the end of every song DRILL FOR SKILL: PARTNER CHANGE RELAY Closing: Appreciate your last partner with a hand shake and high five. INDIVIDUAL ASSESSMENT - WHAT TO LOOK FOR: 1. Does student understand the line dance pattern and how to dance it with the group? 2. Is student dancing the steps to the East Coast Swing correctly? 3. Is student dancing the correct rhythm for the swing? 4. Is student connecting properly in Open Position with partner? [email protected] © Cynthia R. -

Swing Dance I Semester Units/Hours

College of San Mateo Official Course Outline 1. COURSE ID: DANC 167.1 TITLE: Swing Dance I Semester Units/Hours: 0.5 - 1.0 units; a minimum of 24.0 lab hours/semester; a maximum of 48.0 lab hours/semester Method of Grading: Grade Option (Letter Grade or P/NP) 2. COURSE DESIGNATION: Degree Credit Transfer credit: CSU AA/AS Degree Requirements: CSM - GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS: E4: Physical Education CSU GE: CSU GE Area E: LIFELONG LEARNING AND SELF-DEVELOPMENT: E2 3. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS: Catalog Description: Beginning level instruction in several versions of the popular ballroom dance called Swing. This class emphasizes principles of fitness and enjoyment. Attention is paid to proper technique in both the lead and follow dance positions, including proper footwork, alignment and posture. Music is varied to broaden experience with different tempos and styles. No prior experience needed, no partner required. 4. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOME(S) (SLO'S): Upon successful completion of this course, a student will meet the following outcomes: 1. Exhibit swing dance forms by performing an instructor-choreographed routine and appreciate partner and social dance opportunities at the introductory level. 5. SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES: Upon successful completion of this course, a student will be able to: Students are expected to execute the following skills at the Beginning level: 1. Demonstrate at least two specific styles of Swing dance 2. Develop coordination, strength, and agility through dance 3. Demonstrate the rhythm and musicality inherent to Swing dance forms 4. Demonstrate understanding of a dance form and skill acquisition through performance 5. Develop an awareness and appreciation of the cultural, social, and individual forces that contributed to the origins of these art forms 6. -

Swing Dancing

Swing Dancing Richard Powers Street Swing Also known as Bugg and 4-count Hustle I am beginning with 4-count street swing because it's the easiest approach to swing dancing. The reason I start with street swing is that the timing is easy enough to let you concentrate on what's really important in swing: the swing moves, partnering, flexibility and creativity. Once you are comfortable with dancing street swing, it's an easy next step to the more widely-known six- count swing, which is the same four steps done in a slow-slow-quick-quick timing. Then triple six-count swing completes the family. Street swing is an American vernacular dance, meaning grass roots, from the people, instead of from professional dance masters. It's occasionally seen across the U.S. and Europe, although not as frequently as six-count swing. Today, Bugg is especially popular in Sweden. The Footwork for Street Swing Take two walking steps, either forward and back, or done in place, or traveling. Then finish with a "rock step" which is another two steps, first back, then forward, in place. The timing for street swing is an even 1-2-3-4. Walk-walk-rock-step. If you’re doing the steps in place, the Lead’s steps are: 1) Take a small step with the left foot to the left side. 2) Replace weight back on the right foot. 3) Take a small rock step straight back left. 4) Replace weight forward onto the right foot. The Follow dances the mirror image to this, beginning with her right foot. -

Fixity of Form and Collaborative Composition in Duke Ellington's Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue

Jazz Perspectives ISSN: 1749-4060 (Print) 1749-4079 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjaz20 Improvisation as Composition: Fixity of Form and Collaborative Composition in Duke Ellington's Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue Katherine Williams To cite this article: Katherine Williams (2012) Improvisation as Composition: Fixity of Form and Collaborative Composition in Duke Ellington's Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue , Jazz Perspectives, 6:1-2, 223-246, DOI: 10.1080/17494060.2012.729712 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2012.729712 Published online: 11 Jan 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 197 View related articles Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjaz20 Download by: [University of Plymouth] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 08:37 Jazz Perspectives, 2012 Vol. 6, Nos. 1–2, 223–246, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2012.729712 Improvisation as Composition: Fixity of Form and Collaborative Composition in Duke Ellington’s Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue Katherine Williams Pianist, composer and bandleader Edward Kennedy (“Duke”)Ellington(1899– 1974) emerged on the New York City jazzscenein1923.Withinjustafew years, the Ellington band’soriginalrepertoireandperformances were attracting much critical attention. A common theme of the discourse surrounding Ellington from the 1920s was the comparison of his repertoire with European classical music. These -

Jazz Jazz Is a Uniquely American Music Genre That Began in New Orleans Around 1900, and Is Characterized by Improvisation, Stron

Jazz Jazz is a uniquely American music genre that began in New Orleans around 1900, and is characterized by improvisation, strong rhythms including syncopation and other rhythmic invention, and enriched chords and tonal colors. Early jazz was followed by Dixieland, swing, bebop, fusion, and free jazz. Piano, brass instruments especially trumpets and trombones, and woodwinds, especially saxophones and clarinets, are often featured soloists. Jazz in Missouri Both St. Louis and Kansas City have played important roles in the history of jazz in America. Musicians came north to St. Louis from New Orleans where jazz began, and soon the city was a hotbed of jazz. Musicians who played on the Mississippi riverboats were not really playing jazz, as the music on the boats was written out and not improvised, but when the boats docked the musicians went to the city’s many clubs and played well into the night. Some of the artists to come out of St. Louis include trumpeters Clark Terry, Miles Davis and Lester Bowie, saxophonist Oliver Nelson, and, more recently, pianist Peter Martin. Because of the many jazz trumpeters to develop in St. Louis, it has been called by some “City of Gabriels,” which is also the title of a book on jazz in St. Louis by jazz historian and former radio DJ, Dennis Owsley. Jazz in Kansas City, like jazz in St. Louis, grew out of ragtime, blues and band music, and its jazz clubs thrived even during the Depression because of the Pendergast political machine that made it a 24-hour town. Because of its location, Kansas City was connected to the “territory bands” that played the upper Midwest and the Southwest, and Kansas City bands adopted a feel of four even beats and tended to have long solos.