The Semantic Morphological Category of Noun Number in Structurally Different Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computational Analysis of Affixed Words in Malay Language Bali RANAIVO-MALANÇON School of Computer Sciences Universiti Sains Malaysia [email protected]

Computational analysis of affixed words in Malay language Bali RANAIVO-MALANÇON School of Computer Sciences Universiti Sains Malaysia [email protected] A full-system Malay morphological analyser must contain modules that can analyse affixed words, compound words, and reduplicated words. In this paper, we propose an algorithm to analyse automatically Malay affixed words as they appear in a written text by applying successively segmentation, morphographemic, morphotactic, and interpretation rules. To get an accurate analyser, we have classified Malay affixed words into two groups. The first group contains affixed words that cannot be analysed automatically. They are lexicalised affixed words (e.g. berapa, mengapa), idiosyncrasy (e.g. bekerja, penglipur), and infixed words because infixation is not productive any more in Malay language. Affixed words that belong to the first group will be filtered, treated and take off before the segmentation phase. The second group contain affixed words that can be segmented according to segmentation and morphographemic rules. Affixes are classified following their origin (native vs. borrowed), their position in relation to the base (prefix, suffix, circumfix), and the spelling variations they may create when they are added to a base. At the moment, the analyser can process affixed words containing only native prefixes, suffixes and circumfixes. In Malay language, only five native prefixes (ber-, per-, ter-, me-, pe-) may create some modification (deletion, insertion, assimilation) at the point of contact with the base. Thus the main problem in segmenting prefixed words in Malay is to determine the end of the prefix and the beginning of the base. To solve the problem, we state that each affix in Malay has only one form (i.e. -

Representation of Inflected Nouns in the Internal Lexicon

Memory & Cognition 1980, Vol. 8 (5), 415423 Represeritation of inflected nouns in the internal lexicon G. LUKATELA, B. GLIGORIJEVIC, and A. KOSTIC University ofBelgrade, Belgrade, Yugoslavia and M.T.TURVEY University ofConnecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06268 and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 The lexical representation of Serbo-Croatian nouns was investigated in a lexical decision task. Because Serbo-Croatian nouns are declined, a noun may appear in one of several gram matical cases distinguished by the inflectional morpheme affixed to the base form. The gram matical cases occur with different frequencies, although some are visually and phonetically identical. When the frequencies of identical forms are compounded, the ordering of frequencies is not the same for masculine and feminine genders. These two genders are distinguished further by the fact that the base form for masculine nouns is an actual grammatical case, the nominative singular, whereas the base form for feminine nouns is an abstraction in that it cannot stand alone as an independent word. Exploiting these characteristics of the Serbo Croatian language, we contrasted three views of how a noun is represented: (1) the independent entries hypothesis, which assumes an independent representation for each grammatical case, reflecting its frequency of occurrence; (2) the derivational hypothesis, which assumes that only the base morpheme is stored, with the individual cases derived from separately stored inflec tional morphemes and rules for combination; and (3) the satellite-entries hypothesis, which assumes that all cases are individually represented, with the nominative singular functioning as the nucleus and the embodiment of the noun's frequency and around which the other cases cluster uniformly. -

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Animacy, Definiteness, and Case in Cappadocian and Other

Animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and other Asia Minor Greek dialects* Mark Janse Ghent University and Roosevelt Academy, Middelburg This article discusses the relation between animacy, definiteness, and case in Cappadocian and several other Asia Minor Greek dialects. Animacy plays a decisive role in the assignment of Greek and Turkish nouns to the various Cappadocian noun classes. The development of morphological definiteness is due to Turkish interference. Both features are important for the phenom- enon of differential object marking which may be considered one of the most distinctive features of Cappadocian among the Greek dialects. Keywords: Asia Minor Greek dialectology, Cappadocian, Farasiot, Lycaonian, Pontic, animacy, definiteness, case, differential object marking, Greek–Turkish language contact, case typology . Introduction It is well known that there is a crosslinguistic correlation between case marking and animacy and/or definiteness (e.g. Comrie 1989:128ff., Croft 2003:166ff., Linguist List 9.1653 & 9.1726). In nominative-accusative languages, for in- stance, there is a strong tendency for subjects of active, transitive clauses to be more animate and more definite than objects (for Greek see Lascaratou 1994:89). Both animacy and definiteness are scalar concepts. As I am not con- cerned in this article with pronouns and proper names, the person and referen- tiality hierarchies are not taken into account (Croft 2003:130):1 (1) a. animacy hierarchy human < animate < inanimate b. definiteness hierarchy definite < specific < nonspecific Journal of Greek Linguistics 5 (2004), 3–26. Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 09:55:21PM via free access issn 1566–5844 / e-issn 1569–9856 © John Benjamins Publishing Company 4 Mark Janse With regard to case marking, there is a strong tendency to mark objects that are high in animacy and/or definiteness and, conversely, not to mark ob- jects that are low in animacy and/or definiteness. -

Grammatical Gender and Grammatical Stems

Grammatical gender and grammatical stems How many grammatical genders exist in Czech? How can we tell the grammatical gender of a noun? What is a grammatical stem and how do we determine it? Why is knowing the grammatical stem important? How does the ending of a noun help us to know whether it is a hard- or soft-stem noun? Like other European languages (German, French, Spanish) but unlike English, Czech nouns are marked for grammatical gender. Czech has three grammatical genders: Masculine (M), Feminine (F), and Neuter (N). M and F partly overlap with the natural gender of human beings, so we have učitel for a male teacher and učitelka for a female teacher, sportovec for a male athlete and sportovkyně for a female athlete… But grammatical gender is a feature of all nouns (names of inanimate things, places, abstractions…), and it plays an important role in how Czech grammar works. To determine the grammatical gender of a noun (Maskulinum, femininum nebo neutrum?), we look at the ending—the last consonant or vowel—of the word in the Nominative singular (the basic or dictionary form of the word). 1. The great majority of nouns that end in a consonant are Masculine: profesor (professor), hrad (castle), stůl (table), pes (dog), autobus (bus), počítač (computer), čaj (tea), sešit (workbook), mobil (cell-phone)… Masculine nouns can be further divided into animate nouns (people and animals) and inanimate nouns (things, places, abstractions). 2. The great majority of nouns that end in -a are Feminine: profesorka (professor), lampa (lamp), kočka (cat), kniha (book), ryba (fish), fotka (photo), třída (classroom), podlaha (floor), budova (building)… 3. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Class Slides

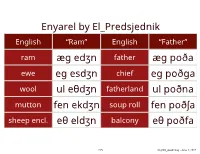

Enyarel by El_Predsjednik English “Ram” English “Father” ram æg edʒn father æg poða ewe eg esdʒn chief eg poðga wool ul eθdʒn fatherland ul poðna mutton fen ekdʒn soup roll fen poðʃa sheep encl. eθ eldʒn balcony eθ poðfa 215 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 HIGH VALYRIAN 216 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 The common language of the Valyrian Freehold, a federation in Essos that was destroyed by the Doom before the series begins. 217 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 218 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 ??????? High Valyrian ?????? 219 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Valar morghulis. “ALL men MUST die.” Valar dohaeris. “ALL men MUST serve.” 220 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Singular, Plural, Collective 221 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Large Number Collective Plural 222 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Number Marking Definite Indefinite Small Number Singular Paucal Large Number Collective Plural 223 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N kastor qintir “green turtle” 224 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val kaːr “man heap” 225 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *valhaːr > *valhar > valar “all men” 226 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 Head Final ADJ — N *val ont > *valon > valun “man hand > some men” 227 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for certain _# Cs, e.g. voiced stops, laterals, voiceless non- coronals, etc. 228 ling183_week2.key - June 1, 2017 SOUND CHANGE Dispreference for monosyllabic words— especially -

Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun Entries – Chapter 3, LFCA Example

Session A3: Introduction to Latin Nouns 1. Noun entries – Chapter 3, LFCA When a Latin noun is listed in a dictionary it provides three pieces of information: The nominative singular, the genitive singular, and the gender. The first form, called nominative (from Latin nömen, name) is the means used to list, or name, words in a dictionary. The second form, the genitive (from Latin genus, origin, kind or family), is used to find the stem of the noun and to determine the declension, or noun family to which it belongs. To find the stem of a noun, simply look at the genitive singular form and remove the ending –ae. The final abbreviation is a reference to the noun’s gender, since it is not always evident by the noun’s endings. Example: fëmina, fëminae, f. woman stem = fëmin/ae 2. Declensions – Chapters 3 – 10, LFCA Just as verbs are divided up into families or groups called conjugations, so also nouns are divided up into groups that share similar characteristics and behavior patterns. A declension is a group of nouns that share a common set of inflected endings, which we call case endings (more on case later). The genitive reveals the declension or family of nouns from which a word originates. Just as the infinitive is different for each conjugation, the genitive singular is unique to each declension. 1 st declension mënsa, mënsae 2 nd declension lüdus, lüdï ager, agrï dönum, dönï 3 rd declension vöx, vöcis nübës, nübis corpus, corporis 4 th declension adventus, adventüs cornü, cornüs 5 th declension fidës, fideï Practice: 1. -

USAN Naming Guidelines for Monoclonal Antibodies |

Monoclonal Antibodies In October 2008, the International Nonproprietary Name (INN) Working Group Meeting on Nomenclature for Monoclonal Antibodies (mAb) met to review and streamline the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme. Based on the group's recommendations and further discussions, the INN Experts published changes to the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme. In 2011, the INN Experts published an updated "International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Biological and Biotechnological Substances—A Review" (PDF) with revisions to the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme language. The USAN Council has modified its own scheme to facilitate international harmonization. This page outlines the updated scheme and supersedes previous schemes. It also explains policies regarding post-translational modifications and the use of 2-word names. The council has no plans to retroactively change names already coined. They believe that changing names of monoclonal antibodies would confuse physicians, other health care professionals and patients. Manufacturers should be aware that nomenclature practices are continually evolving. Consequently, further updates may occur any time the council believes changes are necessary. Changes to the monoclonal antibody nomenclature scheme, however, should be carefully considered and implemented only when necessary. Elements of a Name The suffix "-mab" is used for monoclonal antibodies, antibody fragments and radiolabeled antibodies. For polyclonal mixtures of antibodies, "-pab" is used. The -pab suffix applies to polyclonal pools of recombinant monoclonal antibodies, as opposed to polyclonal antibody preparations isolated from blood. It differentiates polyclonal antibodies from individual monoclonal antibodies named with -mab. Sequence of Stems and Infixes The order for combining the key elements of a monoclonal antibody name is as follows: 1. -

Verbal Case and the Nature of Polysynthetic Inflection

Verbal case and the nature of polysynthetic inflection Colin Phillips MIT Abstract This paper tries to resolve a conflict in the literature on the connection between ‘rich’ agreement and argument-drop. Jelinek (1984) claims that inflectional affixes in polysynthetic languages are theta-role bearing arguments; Baker (1991) argues that such affixes are agreement, bearing Case but no theta-role. Evidence from Yimas shows that both of these views can be correct, within a single language. Explanation of what kind of inflection is used where also provides us with an account of the unusual split ergative agreement system of Yimas, and suggests a novel explanation for the ban on subject incorporation, and some exceptions to the ban. 1. Two types of inflection My main aim in this paper is to demonstrate that inflectional affixes can be very different kinds of syntactic objects, even within a single language. I illustrate this point with evidence from Yimas, a Papuan language of New Guinea (Foley 1991). Understanding of the nature of the different inflectional affixes of Yimas provides an explanation for its remarkably elaborate agreement system, which follows a basic split-ergative scheme, but with a number of added complications. Anticipating my conclusions, the structure in (1c) shows what I assume the four principal case affixes on a Yimas verb to be. What I refer to as Nominative and Accusative affixes are pronominal arguments: these inflections, which are restricted to 1st and 2nd person arguments in Yimas, begin as specifiers and complements of the verb, and incorporate into the verb by S- structure. On the other hand, what I refer to as Ergative and Absolutive inflection are genuine agreement - they are the spell-out of functional heads, above VP, which agree with an argument in their specifier. -

Greek and Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes

GREEK AND LATIN ROOTS, PREFIXES, AND SUFFIXES This is a resource pack that I put together for myself to teach roots, prefixes, and suffixes as part of a separate vocabulary class (short weekly sessions). It is a combination of helpful resources that I have found on the web as well as some tips of my own (such as the simple lesson plan). Lesson Plan Ideas ........................................................................................................... 3 Simple Lesson Plan for Word Study: ........................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Idea 2 ...................................................................................................... 3 Background Information .................................................................................................. 5 Why Study Word Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes? ......................................................... 6 Latin and Greek Word Elements .............................................................................. 6 Latin Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 6 Root, Prefix, and Suffix Lists ........................................................................................... 8 List 1: MEGA root list ................................................................................................... 9 List 2: Roots, Prefixes, and Suffixes .......................................................................... 32 List 3: Prefix List ...................................................................................................... -

Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants

ATLANTIS Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies 39.1 (June 2017): 33-54 issn 0210-6124 | e-issn 1989-6840 Verbal Agreement with Collective Nominal Constructions: Syntactic and Semantic Determinants Yolanda Fernández-Pena Universidade de Vigo [email protected] This corpus-based study investigates the patterns of verbal agreement of twenty-three singular collective nouns which take of-dependents (e.g., a group of boys, a set of points). The main goal is to explore the influence exerted by theof -PP on verb number. To this end, syntactic factors, such as the plural morphology of the oblique noun (i.e., the noun in the of- PP) and syntactic distance, as well as semantic issues, such as the animacy or humanness of the oblique noun within the of-PP, were analysed. The data show the strongly conditioning effect of plural of-dependents on the number of the verb: they favour a significant proportion of plural verbal forms. This preference for plural verbal patterns, however, diminishes considerably with increasing syntactic distance when the of-PP contains a non-overtly- marked plural noun such as people. The results for the semantic issues explored here indicate that animacy and humanness are also relevant factors as regards the high rate of plural agreement observed in these constructions. Keywords: agreement; collective; of-PP; distance; animacy; corpus . Concordancia verbal con construcciones nominales colectivas: sintaxis y semántica como factores determinantes Este estudio de corpus investiga los patrones de concordancia verbal de veintitrés nombres colectivos singulares que toman complementos seleccionados por la preposición of, como en los ejemplos a group of boys, a set of points.