Qualitative Analysis of the Impact of a Mass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

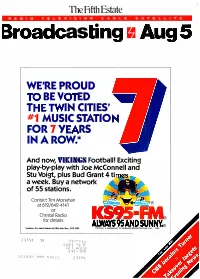

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

Jhonormedal2012.Pdf

The Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism Monday, Oct. 15, 2012 ReynoldsAlumni Center University of Missouri Elmer Lower Dean, Missouri School ofJournalism 1g82-83 The 2012 Missouri Honor Medal activities are dedicated to Elmer Lower, who served as dean of the Missouri School of Journalism from 1982-83. Lower, a Kansas City native, graduated from the School of Journalism in 1933. From his humble beginning as a $10-a-week courthouse reporter for a newspaper in Kentucky, he would serve many years as a distinguished print reporter. With the advent of television news, Lower joined CBS in 1953 and would become an industry pioneer. His journalism career culminated with the presidency of ABC News. For Lower's accomplishments, he received an Emmy for lifetime achievement. In 1959, the School recognized Lower with a Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism. Thanks to the support of many friends and alumni, the Missouri School of Journalism named a bench near Lower's old office in his honor. Schedule 6-7p.m. Reception 7p.m. Banquet Presentation of Medals Dean Mills Dean, Missouri School of Journalism David Bradley Chairman, University of Missouri Board of Curators CEO, News-Press & Gazette Company of St. Joseph, Mo. Aboutthe Missouri Honor Medal The Missouri School of Journalism has awarded its Missouri Honor Medal for Distinguished Service in Journalism since 1930. Medalists are selected by the faculty of the School on the basis of lifetime or superior achievement, for distinguished service performed in such lines of journalistic endeavor as shall be selected each year for consideration. -

[IRE Journal Issue Irejournalmayjun2004; Thu Apr 1

CONTENTSFEATURES THE IRE JOURNAL 20 - 29 TRACKING SEX OFFENDERS TABLE OF CONTENTS MAY/JUNE 2004 OFFENDER SCREENING Likely predators released 4 Media insurers may push despite red-flag testing strong journalism training By John Stefany to manage risks, costs (Minnneapolis) Star Tribune By Brant Houston The IRE Journal STATE REGISTRY System fails to keep tabs 10 Top investigative work on released sex offenders named in 2003 IRE Awards By Frank Gluck By The IRE Journal The (Cedar Rapids, Iowa) Gazette 14 2004 IRE Conference to feature best in business COACHING THREAT By The IRE Journal Abuse of female athletes often covered up, ignored 16 BUDGET PROPOSAL By Christine Willmsen Organization maintains steady, conservative The Seattle Times course in light of tight training, data budgets in newsrooms By Brant Houston The IRE Journal 30 IMMIGRANT PROFILING 18 PUBLIC RECORDS Arabs face scrutiny in Detroit area Florida fails access test in joint newspaper audit in two years following 9/11 terrorist attacks By John Bebow By Chris Davis and Matthew Doig for The IRE Journal Sarasota Herald-Tribune 19 FOI REPORT 32 Irreverent approach to freelancing Privacy exemptions explains the need to break the rules may prove higher hurdle By Steve Weinberg than national security The IRE Journal By Jennifer LaFleur Checking criminal backgrounds The Dallas Morning News 33 By Carolyn Edds The IRE Journal ABOUT THE COVER 34 UNAUDITED STATE SPENDING Law enforcement has a tough Yes, writing about state budgets can sometimes be fun time keeping track of sexual By John M.R. Bull predators – often until they The (Allentown, Pa.) Morning Call re-offend and find themselves 35 LEGAL CORNER back in custody. -

NOMINEES for the 31St ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED by the NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS &

NOMINEES FOR THE 31st ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Winners to be announced on September 27th at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frederick Wiseman to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, N.Y. – July 15, 2010 – Nominations for the 31st Annual News and Documentary Emmy ® Awards were announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy ® Awards will be presented on Monday, September 27 at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. Emmy ® Awards will be presented in 41 categories, including Breaking News, Investigative Reporting, Outstanding Interview, and Best Documentary, among others. “From the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the struggling American economy, to the inauguration of Barack Obama, 2009 was a significant year for major news stories,” said Bill Small, Chairman of the News & Documentary Emmy ® Awards. “The journalists and documentary filmmakers nominated this year have educated viewers in understanding some of the most compelling issues of our time, and we salute them for their efforts.” This year’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award will be given to Frederick Wiseman, one of the most accomplished documentarians in the history of the medium. In a career spanning almost half a century, Wiseman has produced, directed and edited 38 films. His documentaries comprise a chronicle of American life unmatched by perhaps any other filmmaker. -

31St Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES 31st Annual News & Documentary EMMY AWARDS CONGRATULATES THIS YEAR’S NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES AND HONOREES WEEKDAYS 7/6 c CONGRATULATES OUR NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES Outstanding Continuing Coverage of a News Story in a Regularly Scheduled Newscast “Inside Mexico’s Drug Wars” reported by Matthew Price “Pakistan’s War” reported by Orla Guerin WEEKDAYS 7/6 c 31st ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT / FREDERICK WISEMAN CHAIRMAN’S AWARD / PBS NEWSHOUR EMMY®AWARDS PRESENTED IN 39 CATEGORIES NOMINEES NBC News salutes our colleagues for the outstanding work that earned 22 Emmy Nominations st NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION CUSTOM 5 ARTS & SCIENCES / ANNUAL NEWS & SUPPLEMENT 31 DOCUMENTARY / EMMY AWARDS / NEWSPRO 31st Annual News & Documentary Letter From the Chairman Emmy®Awards Tonight is very special for all of us, but especially so for our honorees. NATAS Presented September 27, 2010 New York City is proud to honor “PBS NewsHour” as the recipient of the 2010 Chairman’s Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism. Thirty-five years ago, Robert MacNeil launched a nightly half -hour broadcast devoted to national and CONTENTS international news on WNET in New York. Shortly thereafter, Jim Lehrer S5 Letter from the Chairman joined the show and it quickly became a national PBS offering. Tonight we salute its illustrious history. Accepting the Chairman’s Award are four S6 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT dedicated and remarkable journalists: Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer; HONOREE - FREDERICK WISEMAN longtime executive producer Les Crystal, who oversaw the transition of the show to an hourlong newscast; and the current executive producer, Linda Winslow, a veteran of the S7 Un Certain Regard By Marie-Christine de Navacelle “NewsHour” from its earliest days. -

NOMINEES for the 40Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 40th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED NBC’s Andrea Mitchell to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award September 24th Award Presentation at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 25, 2019 (revised 8.19.19) – Nominations for the 40th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019, at a ceremony at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “The clear, transparent, and factual reporting provided by these journalists and documentarians is paramount to keeping our nation and its citizens informed,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “Even while under attack, truth and the hard-fought pursuit of it must remain cherished, honored, and defended. These talented nominees represent true excellence in this mission and in our industry." In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to honor Andrea Mitchell, NBC News’ chief foreign affairs correspondent and host of MSNBC's “Andrea Mitchell Reports," with the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award for her groundbreaking 50-year career covering domestic and international affairs. The 40th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar -

85Th National Headliner Awards Radio and TV Winners

85th National Headliner Awards Radio and TV winners The 85th National Headliner Award winners honoring the best journalism for radio and television stations were announced today. The awards were founded in 1934 by the Press Club of Atlantic City. The annual contest is one of the oldest and largest in the country that recognizes journalistic merit in the communications industry. The print and online awards will be announced on Monday. The Best in Show for radio was a story by NPR’s Yuki Noguchi titled “Anguished Families Shoulder The Biggest Burdens Of Opioid Addiction.” The judges complimented the story for its “extraordinary and excruciating detail of the physical and financial costs of drug addiction. Information most of us probably have never thought of, but should have.” The Best in Show award for television went to the staff at CBS News’ “48 Hours” for a story titled “Click for a Killer.” “From the darkest recesses of the Internet to arrests on various continents, CBS’s ‘48 Hours’ leads us on a bizarre yet penetrating investigation into the world of murder for hire,” the judges said of the story. Congratulations to all of this year’s winners! Below is the complete list. RADIO STATIONS Radio stations newscast, all markets First Place “A Blue Wave” Texas Standard staff Texas Standard, Austin, Texas Judges’ comments: Good mix of experts with attention paid to diversity and inclusion. Clips and soundbites from reporters and the people whom they interviewed make for a thorough picture of midterm results' who, how and why. Second Place WTOP staff WTOP-FM, Washington, D.C. -

The Society of Environmental Journalists to Cover December’S COP15 Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen and the to Convene in Wisconsin

NP40_partials.qxp 9/28/09 12:20 PM Page 1 October 2009 Survey Results LOCAL WARMING Environmental Journalists put a journalists worry community focus on about resources a global issue Page 16 Freelancers Fight a Glut Scratching out work in a crowded marketplace Page 5 Is TV News on the Ball? Why the ACORN story should have come from the pros Page 50 COVER IMAGE BY GIO ALMA WTVJ-TV’S JEFF BURNSIDE 09np0012.qxp 7/21/09 11:12 AM Page 1 The Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Awards HONORING THE BEST IN BROADCAST NEWS FOR 40 YEARS www.dupont.org 09np0012.pdf RunDate: 08/ 03 /09 Full Page Color: 4/C NP40_partials.qxp 9/28/09 12:28 PM Page 2 FROM THE EDITOR The Beat Goes On Welcome to NewsPro’s special Enviro-Journalism issue. The environment remains a crucial beat with ongoing CONTENTS developments that affect all aspects of our future. And despite the crunch of shrunken resources being felt throughout the OCTOBER 2009 business, dedicated news organizations are finding ways to keep it fully covered. FEEDS As you will learn in these pages, the Society of Environmental Newspapers and TV newsrooms Journalists plays no small role in helping its members stay merging to cut costs ..... Page 4 abreast of the field, and one of the organization’s key contributions is its annual conference, where new ideas are Journalists scramble for work in a exchanged and vital information imparted. It’s being held this crowded freelance market ...... Page 5 year in Madison, Wis., Oct. 7-11. -

ELECTION HOMESTRETCH Bush Headlines Dukakis Budget ‘Mess’ URY 18 — Story on Page 3 Mdad

ERAM IP . Cap 19 OTA lY r. AC 19 iC. iR I iianrtefitrr Mmli iO Manchester, Conn. — A City of Village Charm OLN 30 Cents !AR dad 19 S' pa, A C ELECTION HOMESTRETCH Bush headlines Dukakis budget ‘mess’ URY 18 — Story on page 3 Mdad IC. lad JT % AP photo CLOSE TO VICTORY - A jubilant Vice after a speech at Fairfield University Bush a wide margin over Demorr««r President George Bush receives applause Friday. All national polls continue to give presidential candidate Michael Du^kakis - w m m ii i. V .«♦ t»t ♦ ♦»*1 i < • » I'l’tVt'i’i t , 1 j i , < « « t‘tV»V*'t 111 t r t'l' M t ! I Tt’i'i’i'i : ' ' V . .* * I ' Connecticat Weather IRS ruling could illegalize Bush assails REGIONALWEATHER Dukakis on Accu-Weather® forecast for Saturday condo owners’ tax breaks Daytime CotKfitions and High Temperatures Hundreds of condominium said. statement that while a private- owners across the state could be budget ‘mess’ Some of those who participate letter ruling applies to a single affected by an Internal Revenue in such tax districts have taken case, it can be applied in other Service ruling that makes it property tax deductions on fed cases in which facts and circum By David Espo illegal for members of property eral income tax returns, but the stances are similar. The Associated Press owners associations to claim tax IRS said in its ruling that in some Holsten said he didn’t know exemptions for security, road cases these deductions are exactly how many people are George Bush brandished a newspaper headline maintenance and other costs. -

Projectreport.Pdf (4.019Mb)

USE OF NARRATIVE STYLE IN BROADCAST NEWS JENNIFER KRISTIN LONG MAY 2013 Randy Reeves, Chair Kent Collins Greeley Kyle To my parents: Thank you for being the rock I know I can turn to for emotional, mental and financial guidance. If it weren’t for you two I might be in a ditch in Kansas somewhere because I didn’t have the cash to rotate my tires before road tripping across the heartland. Thank you for paying for my hotel in Madison and my gas in Minneapolis. Your faith in me and in this project is what made it special. If it weren’t for your investment it just wouldn’t have been possible and for that I’m extremely thankful. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4,500 miles, countless coffees and one too many karaoke sessions later, this project turned out being much more than I ever thought it could be. I went to places I never thought I would go and met so many great journalists I never dreamed of talking to in person. From knocking on trailer doors in Beloit, Wisconsin, to hiking through the muddy trails of Big South Fork Tennessee, this project let me see some of the best journalists and storytellers at work. Even the dream of doing this project would not have been possible without the support and love of my family, friends and the faculty members at the University of Missouri School of Journalism. The biggest support came from my graduate faculty committee members. I truly believe I had the best committee a girl could ever ask for. -

[IRE Journal Issue Irejournaljulyaug2004; Wed Jun

CONTENTSFEATURES THE IRE JOURNAL TABLE OF CONTENTS JULY/AUGUST 2004 18 - 27 INVESTIGATIONS OFF BREAKING NEWS 4 NICAR has served roles as educator, incubator FLIGHT 5481 in 10-year IRE association Fatal crash reveals commuter airplane By Brant Houston maintenance flaws The IRE Journal By Ames Alexander The Charlotte Observer 6 Annual conference draws more than 900 to Atlanta By The IRE Journal staff SHUTTLE BREAKUP Disaster plan helps 8 PEACE CORPS team to keep focus Violence against volunteers worldwide in yearlong probe found in database checks, interviews By John Kelly By Russell Carollo Florida Today Dayton (Ohio) Daily News CLUB FIRE 10 CHARITY ACCOUNTABILITY ‘Who died and why’ serves as Scrutiny shows leading environmental group focus after 100 perish cut insider deals, drilled for oil in sensitive area By Thomas E. Heslin By Joe Stephens The Providence (R.I.) Journal The Washington Post BLACKOUT 12 NONPROFITS Power shortages, interruptions Charities lend millions to officers, directors could become more common story By Harvy Lipman By The IRE Journal staff The Chronicle of Philanthropy 14 HANDSHAKE HOTELS 28 Turning your investigations Radio reporters find hidden into books costs of NYC homeless housing deals By Steve Weinberg By Andrea Bernstein and Amy Eddings The IRE Journal WNYC-New York Public Radio 29 POWER PLAYS 15 FOI REPORT Varied state records show Summer records work perfect election preparation abuse of power by public officials By Charles Davis By Phil Williams and Bryan Staples WTVF-Nashville 16 PLEA DEALS Criminals avoid felony records even after pleading guilty 30 Plenty of election year left By Jason Grotto and Manny Garcia for pursuing campaign stories The Miami Herald By Aron Pilhofer and Derek Willis The Center for Public Integrity ABOUT THE COVER 32 VOTING RECORDS Disaster and aftermath Mapping and analysis provide deeper grasp of Justice Department’s balloting investigation pictures from Florida Today, By Scott Fallon and Benjamin Lesser The Providence Journal The (Bergen, N.J.) Record and The Charlotte Observer. -

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: TELEVISING the SPACE AGE: a DESCRIPTIVE CHRONOLOGY of CBS NEWS SPECIAL COVERAGE of SPACE EXPLORATION

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: TELEVISING THE SPACE AGE: A DESCRIPTIVE CHRONOLOGY OF CBS NEWS SPECIAL COVERAGE OF SPACE EXPLORATION FROM 1957 TO 2003 Alfred Robert Hogan, Master of Arts, 2005 Thesis directed by: Professor Douglas Gomery College of Journalism University of Maryland, College Park From the liftoff of the Space Age with the Earth-orbital beeps of Sputnik 1 on 4 October 1957, through the videotaped tragedy of space shuttle Columbia’s reentry disintegration on 1 February 2003 and its aftermath, critically acclaimed CBS News televised well more than 500 hours of special events, documentary, and public affairs broadcasts dealing with human and robotic space exploration. Much of that was memorably anchored by Walter Cronkite and produced by Robert J. Wussler. This research synthesizes widely scattered data, much of it internal and/or unpublished, to partially document the fluctuating patterns, quantities, participants, sponsors, and other key details of that historic, innovative, riveting coverage. TELEVISING THE SPACE AGE: A DESCRIPTIVE CHRONOLOGY OF CBS NEWS SPECIAL COVERAGE OF SPACE EXPLORATION FROM 1957 TO 2003 by Alfred Robert Hogan Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2005 Advisory Committee: Professor Douglas Gomery, Chair Mr. Stephen Crane, Director, Capital News Service Washington Bureau Professor Lee Thornton. © Copyright by Alfred Robert Hogan 2005 ii Dedication To all the smart, energetic, talented people who made the historic start of the Space Age an unforgettable reality as it unfolded on television; to my ever-supportive chief adviser Professor Douglas Gomery and the many others who kindly took time, effort, and pains to aid my research quest; and to my special personal circle, especially Mother and Father, Cindy S.