093 Bulwer's Petrel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seabirds in Southeastern Hawaiian Waters

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 30, Number 1, 1999 SEABIRDS IN SOUTHEASTERN HAWAIIAN WATERS LARRY B. SPEAR and DAVID G. AINLEY, H. T. Harvey & Associates,P.O. Box 1180, Alviso, California 95002 PETER PYLE, Point Reyes Bird Observatory,4990 Shoreline Highway, Stinson Beach, California 94970 Waters within 200 nautical miles (370 km) of North America and the Hawaiian Archipelago(the exclusiveeconomic zone) are consideredas withinNorth Americanboundaries by birdrecords committees (e.g., Erickson and Terrill 1996). Seabirdswithin 370 km of the southern Hawaiian Islands (hereafterreferred to as Hawaiian waters)were studiedintensively by the PacificOcean BiologicalSurvey Program (POBSP) during 15 monthsin 1964 and 1965 (King 1970). Theseresearchers replicated a tracklineeach month and providedconsiderable information on the seasonaloccurrence and distributionof seabirds in these waters. The data were primarily qualitative,however, because the POBSP surveyswere not basedon a strip of defined width nor were raw counts corrected for bird movement relative to that of the ship(see Analyses). As a result,estimation of density(birds per unit area) was not possible. From 1984 to 1991, using a more rigoroussurvey protocol, we re- surveyedseabirds in the southeasternpart of the region (Figure1). In this paper we providenew informationon the occurrence,distribution, effect of oceanographicfactors, and behaviorof seabirdsin southeasternHawai- ian waters, includingdensity estimatesof abundant species. We also document the occurrenceof six speciesunrecorded or unconfirmed in thesewaters, the ParasiticJaeger (Stercorarius parasiticus), South Polar Skua (Catharacta maccormicki), Tahiti Petrel (Pterodroma rostrata), Herald Petrel (P. heraldica), Stejneger's Petrel (P. Iongirostris), and Pycroft'sPetrel (P. pycrofti). STUDY AREA AND SURVEY PROTOCOL Our studywas a piggybackproject conducted aboard vessels studying the physicaloceanography of the easterntropical Pacific. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Important Bird Areas in Hawaii Elepaio Article

Globally Important Bird Areas in the Hawaiian Islands: Final Report Dr. Eric A. VanderWerf Pacific Rim Conservation 3038 Oahu Avenue Honolulu, HI 96822 9 June 2008 Prepared for the National Audubon Society, Important Bird Areas Program, Audubon Science, 545 Almshouse Road, Ivyland, PA 18974 3 of the 17 globally Important Bird Areas in Hawai`i, from top to bottom: Lehua Islet Hanawī Natural Area Reserve, Maui Hanalei National Wildlife Refuge, Kauai All photos © Eric VanderWerf Hawaii IBAs VanderWerf - 2 INTRODUCTION TO THE IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS PROGRAM The Important Bird Areas (IBA) Program is a global effort developed by BirdLife International, a global coalition of partner organizations in more than 100 countries, to assist with identification and conservation of areas that are vital to birds and other biodiversity. The IBA Program was initiated by BirdLife International in Europe in the 1980's. Since then, over 8,000 sites in 178 countries have been identified as Important Bird Areas, with many national and regional IBA inventories published in 19 languages. Hundreds of these sites and millions of acres have received better protection as a result of the IBA Program. As the United States Partner of BirdLife International, the National Audubon Society administers the IBA Program in the U.S., which was launched in 1995 (see http://www.audubon.org/bird/iba/index.html). Forty-eight states have initiated IBA programs, and more than 2,100 state-level IBAs encompassing over 220 million acres have been identified across the country. Information about these sites will be reviewed by the U.S. IBA Committee to confirm whether they qualify for classification as sites of continental or global significance. -

Cytochrome-B Evidence for Validity and Phylogenetic Relationships of Pseudobulweria and Bulweria (Procellariidae)

The Auk 115(1):188-195, 1998 CYTOCHROME-B EVIDENCE FOR VALIDITY AND PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF PSEUDOBULWERIA AND BULWERIA (PROCELLARIIDAE) VINCENT BRETAGNOLLE,•'5 CAROLE A3VFII•,2 AND ERIC PASQUET3'4 •CEBC-CNRS, 79360 Beauvoirsur Niort, France; 2Villiers en Bois, 79360 Beauvoirsur Niort, France; 3Laboratoirede ZoologieMammi•res et Oiseaux,Museum National d'Histoire Naturelie, 55 rue Buffon,75005 Paris, France; and 4Laboratoirede Syst•matiquemol•culaire, CNRS-GDR 1005, Museum National d'Histoire Naturelie, 43 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France ABSTRACT.--Althoughthe genus Pseudobulweria was described in 1936for the Fiji Petrel (Ps.macgillivrayi), itsvalidity, phylogenetic relationships, and the number of constituenttaxa it containsremain controversial. We tried to clarifythese issues with 496bp sequencesfrom the mitochondrialcytochrome-b gene of 12 taxa representingthree putative subspecies of Pseudobulweria,seven species in six othergenera of the Procellariidae(fulmars, petrels, and shearwaters),and onespecies each from the Hydrobatidae(storm-petrels) and Pelecanoidi- dae (diving-petrels).We alsoinclude published sequences for two otherpetrels (Procellaria cinereaand Macronectesgiganteus ) and use Diomedeaexulans and Pelecanuserythrorhynchos as outgroups.Based on thepronounced sequence divergence (5 to 5.5%)and separate phylo- genetichistory from othergenera that havebeen thought to be closelyrelated to or have beensynonymized with Pseudobulweria,we conclude that the genusis valid, and that the MascarenePetrel (Pseudobulweria aterrima) -

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-B 17 January 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species 02 05 Restore Canada Jay as the English name of Perisoreus canadensis 03 13 Recognize two genera in Stercorariidae 04 15 Split Red-eyed Vireo (Vireo olivaceus) into two species 05 19 Split Pseudobulweria from Pterodroma 06 25 Add Tadorna tadorna (Common Shelduck) to the Checklist 07 27 Add three species to the U.S. list 08 29 Change the English names of the two species of Gallinula that occur in our area 09 32 Change the English name of Leistes militaris to Red-breasted Meadowlark 10 35 Revise generic assignments of woodpeckers of the genus Picoides 11 39 Split the storm-petrels (Hydrobatidae) into two families 1 2018-B-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 280 Split Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus into four species Effect on NACC: This proposal would change the species circumscription of Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus by splitting it into four species. The form that occurs in the NACC area is nominate pacificus, so the current species account would remain unchanged except for the distributional statement and notes. Background: The Fork-tailed Swift Apus pacificus was until recently (e.g., Chantler 1999, 2000) considered to consist of four subspecies: pacificus, kanoi, cooki, and leuconyx. Nominate pacificus is highly migratory, breeding from Siberia south to northern China and Japan, and wintering in Australia, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The other subspecies are either residents or short distance migrants: kanoi, which breeds from Taiwan west to SE Tibet and appears to winter as far south as southeast Asia. -

Value Island Biodiversity It’S Our Life!

VALUE ISLAND BIODivERSITY It’s Our Life! Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme 1 CONTENTS Introduction Introduction David Sheppard, Director SPREP 3 VALUE ISLAND BIODIVERSITY Campaign Launch Kosi Latu, Deputy Director SPREP 5 It’s Our Life! Pacific getting ready to meet new targets 6 Emerald of the Isles 7 David Sheppard, Director, SPREP Rare giant box crab 7 he Pacific islands region swung into action The hive of activity across the region culmi- Micronesia’s Go Local 9 T with determination to observe 2010 as the nated at the 10th Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD International Year of Biodiversity (IYOB). COP10) in Nagoya, Japan. The region’s COP10 Climate Change and Invasive Species 10 communication strategy, The Pacific Voyage, The Biodiversity Bus 11 In 2009 following discussions with participants a flower, was used to convey the over-arch- highlighted the unique biodiversity of the Pa- at the Nature Conservation Roundtable held in ing message that we are all intertwined with cific islands and showcased our PYOB activities Pacific Ocean for your Children 12 Solomon Islands, a draft framework for imple- nature. to the world. The Pacific Voyage also served to menting the International Year of Biodiversity enable the Pacific islands to be heard during The slogan, Value Island Biodiversity – it’s our life, (IYOB) in the Pacific was circulated regionally negotiations and discussions as one voice. And Island Wear Biodiversity and Fashion 13 resounded well with many of SPREP’s Pacific for comment and input. Member countries and we were successful! Issues of importance to island members and was used extensively in territories then endorsed the framework at the the region – invasive species, climate change, Polynesia, Micronesia Challenged 18 correspondence and other publications, and 20th SPREP Meeting held in Apia in 2009 and coastal and marine biodiversity and financing on stickers and posters. -

Vocal Repertoire of the Tahiti Petrel Pseudobulweria Rostrata: a Preliminary Assessment

Rauzon & Rudd: Vocal repertoire of Tahiti Petrel 143 VOCAL REPERTOIRE OF THE TAHITI PETREL PSEUDOBULWERIA ROSTRATA: A PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT MARK J. RAUZON1 & ALEXIS B. RUDD2 1Laney College, Geography Department, 900 Fallon St. Oakland, CA 94607, USA ([email protected]) 2Marine Mammal Research Program, Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology, P.O. Box 1106, Kane’ohe, Hawai’i 96744, USA Received 7 February 2013, accepted 15 May 2014 Tahiti Petrel captured on Mt. Lata, December 2002 (Photo: M. Fialua). SUMMARY RAUZON, M.J. & RUDD, A.B. 2014. Vocal repertoire of Tahiti Petrel Pseudobulweria rostrata: a preliminary assessment. Marine Ornithology 42: 143–148. The Tahiti Petrel Pseudobulweria rostrata is a little-known seabird of tropical Pacific islands. Nocturnal at the colony and a burrow nester, the species relies on acoustic signals to communicate. Its vocalizations have not been intensively studied, and our study is the first to analyze the vocalizations made by the Tahiti Petrel in American Samoa. We found two main vocalizations, a ground call and an aerial call. The ground call consists of seven parts that allow variation to occur in duration and frequency in any portion of the call. That would be important to individual and gender variation, which may be critical to finding mates in burrows in the montane rainforest. The aerial call appears to be a condensed version of the ground call, used when approaching the colony in fog and darkness, and may have echolocating qualities. The Pseudobulweria genus has uncertain evolutionary relationships among petrels, and vocalization may provide a link to ancestral relationships to help better understand evolution of this group. -

Conservation Status of New Zealand Birds, 2008

Notornis, 2008, Vol. 55: 117-135 117 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. Conservation status of New Zealand birds, 2008 Colin M. Miskelly* Wellington Conservancy, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 5086, Wellington 6145, New Zealand [email protected] JOHN E. DOWDING DM Consultants, P.O. Box 36274, Merivale, Christchurch 8146, New Zealand GRAEME P. ELLIOTT Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, Private Bag 5, Nelson 7042, New Zealand RODNEY A. HITCHMOUGH RALPH G. POWLESLAND HUGH A. ROBERTSON Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand PAUL M. SAGAR National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research, P.O. Box 8602, Christchurch 8440, New Zealand R. PAUL SCOFIELD Canterbury Museum, Rolleston Ave, Christchurch 8001, New Zealand GRAEME A. TAYLOR Research & Development Group, Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10420, Wellington 6143, New Zealand Abstract An appraisal of the conservation status of the post-1800 New Zealand avifauna is presented. The list comprises 428 taxa in the following categories: ‘Extinct’ 20, ‘Threatened’ 77 (comprising 24 ‘Nationally Critical’, 15 ‘Nationally Endangered’, 38 ‘Nationally Vulnerable’), ‘At Risk’ 93 (comprising 18 ‘Declining’, 10 ‘Recovering’, 17 ‘Relict’, 48 ‘Naturally Uncommon’), ‘Not Threatened’ (native and resident) 36, ‘Coloniser’ 8, ‘Migrant’ 27, ‘Vagrant’ 130, and ‘Introduced and Naturalised’ 36. One species was assessed as ‘Data Deficient’. The list uses the New Zealand Threat Classification System, which provides greater resolution of naturally uncommon taxa typical of insular environments than the IUCN threat ranking system. New Zealand taxa are here ranked at subspecies level, and in some cases population level, when populations are judged to be potentially taxonomically distinct on the basis of genetic data or morphological observations. -

Christmas Shearwater Egg Dimensions and Shell Characteristics on Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Short Communications Wilson Bull., 11 l(3), 1999, pp. 421-422 Christmas Shearwater Egg Dimensions and Shell Characteristics on Laysan Island, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands G. C. Whittow1,2 and M. B. Naughton ABSTRACT-The mean fresh egg mass of Christ- counted the number of pores in the shell of ran- mas Shearwaters (Puflnus nativitatis) on Laysan Is- domly-selected sub-samples of eggs after drying land, in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, was 44.9 the shells in a desiccator. We measured pore 2 3.4 (SD) g, and the mean egg volume was 42.3 2 2.9 cm3. The measured length and breadth of the eggs, density using the procedure described by Tyler the shell mass, shell thickness, and number of pores in (1953) and Roudybush and coworkers (1980). the shell were within 10% of predictions for procel- The mean fresh egg mass of 18 Christmas lariiform birds, based on fresh egg mass or on both Shearwater eggs was 44.9 -C 3.4 (SD) g. fresh egg mass and incubation period. These data con- Knowledge of the fresh egg mass provides an form with evidence that there are few allometric dif- opportunity to compare some of the other mea- ferences between the eggs of tropical Procellariiformes and those of Procellariiformes from higher latitudes. sured values (Table 1) with predictions for pro- Received 19 Oct. 1998, accepted 25 Feb. 1999. cellariiform eggs, based on the mass of their freshly laid eggs (Rahn and Whittow 1988). There are no predictive equations for the vol- ume of the eggs of Procellariiformes, but mea- The Christmas Shearwater (Puffinus nativ- sured egg lengths and breadths were similar it&is) is a tropical procellariiform seabird that (100.3% and 96.0%, respectively) to predicted breeds on islands in the central North and values (Table 1). -

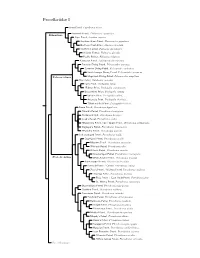

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Seabird Observations Off Western Mexico

SEABIRD OBSERVATIONS OFF WESTERN MEXICO STEVE N. G. HOWELL, Point ReyesBird Observatory,4990 ShorelineHighway, StinsonBeach, California94970 STEVEN J. ENGEL, 1324 SecondStreet, Bismarck,North Dakota 58501 Southern Mexico's offshore Pacific avifauna has been rather little studied. Murphy (1958) and Jehl (1974) reportedobservations from cruisesthat passedthrough Mexican waters in Novemberand December1956 and in April 19.73, respectively.Pitman (1986) mappedthe relativeabundance of 57 speciesof seabirdsin the easterntropical Pacific on the basison 4333 hoursof observationbetween 1974 and 1984; only a small number of these4333 hours(81 noon positions,55 of which were off Baja Califor- nia), however,pertain to Mexicanwaters (i.e., within 200 nauticalmiles of Mexican territow), and 74% of the 81 noon positionswere between Octoberand March (R. L. Pitmanpers. comm.).Pitman's atlas provides an excellentlarge-scale picture but lacks data on seasonalstatus of species,and the scale employeddoes not enable one to interpret local distributions. Other recordsof seabirdsoff western Mexico are widely scatteredand mostlyderive from nearshoreland-based trips of a day or less(e.g., Binford 1970, 1989). The Middle AmericanTrench runs from the vicinityof the IslasTres Marias,Mexico, to the CocosRidge, south of CostaRica. The trenchlies some 55-110 km (mean distance 75 km) offshore between Jalisco and Guerreroand is 15-50 km (mostly20-30 km) wide. The trenchis at least 3600 m deep, mostly4300-4650 m deep from centralJalisco south, and increasesto 5000-5200 m deep off central Guerrero;submarine moun- tains in the trench off Colima (Manzanillo)and Guerrero (Zihuatanejo) reduce depths to 3600 m. On either side of the trench waters quickly shallowto 2700-3200 m, and inshorethe 1000-fathom (1800-m) contour line lies 20-55 km (mostly35-55 km) off the coast. -

Shearwatersrefs V1.10.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2018 & 2019 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Ashley Fisher (www.scillypelagics.com) for the cover images. All images © the photographer. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.3 accessed August 2017]). Version Version 1.10 (January 2018). Cover Main image: Great Shearwater. At sea 3’ SW of the Bishop Rock, Isles of Scilly. 8th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Vignette: Sooty Shearwater. At sea off the Isles of Scilly. 14th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Species Page No. Audubon's Shearwater [Puffinus lherminieri] 34 Balearic Shearwater [Puffinus mauretanicus] 28 Bannerman's Shearwater [Puffinus bannermani] 37 Barolo Shearwater [Puffinus baroli] 38 Black-vented Shearwater [Puffinus opisthomelas] 30 Boyd's Shearwater [Puffinus boydi] 38 Bryan's Shearwater [Puffinus bryani] 29 Buller's Shearwater [Ardenna bulleri] 15 Cape Verde Shearwater [Calonectris edwardsii] 12 Christmas Island Shearwater [Puffinus nativitatis] 23 Cory's Shearwater [Calonectris borealis] 9 Flesh-footed Shearwater [Ardenna carneipes] 21 Fluttering