Raze Or Recycle: the Challenge of 'Recycling' Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Borough of Windsor & Maidenhead Planning Committee

ROYAL BOROUGH OF WINDSOR & MAIDENHEAD PLANNING COMMITTEE DEVELOPMENT CONTROL PANEL 3 March 2021 Item: 1 Application 20/01251/OUT No.: Location: Site Known As Nicholson Quarter Bound By High Street And Broadway Maidenhead Proposal: Hybrid planning application (part-outline, part-full) for comprehensive mixed-use redevelopment of the site including: (1) OUTLINE planning application (with all matters reserved) for four buildings that range in height, with the highest being 88.70m AOD and the lowest being 66.20m AOD, on the site for a comprehensive mixed-use redevelopment comprising: Residential Institutions (Class C2) - up to 29,400 m2 (GEA); Business Use (Class B1) - up to 29,700 m2 (GEA); Flexible Retail, financial and professional services, restaurants and cafes, drinking establishments, hot food takeaways, non-residential institutions and assembly and leisure (Class A1 / A2 / A3 / A4 / A5 / D1 / D2) - up to 4,400 m2 (GEA); Parking and plant space - up to 13,600 m2 (GEA); Formation of new pedestrian and vehicular access; Means of access and circulation and car parking within the site; and Provision of new public open space and landscaping. (2) FULL planning application for the demolition of all existing buildings on site, except Nicholsons House and Brock House, site preparation, construction of two residential buildings comprising 25 storeys, and part 15/part 10 storey and a landscaped podium (Class C3), construction of a 4 storey office building (Class B1), the provision of a new public open space, and landscaping and the erection of a multi-storey car park and flexible retail, financial and professional services, restaurant and cafes, drinking establishments, assembly and leisure uses (Class A1 / A2 / A3 / A4 / A5 / D1 / D2). -

Smart Parking System with Dynamic Pricing, Edge-Cloud Computing and Lora

sensors Article Smart Parking System with Dynamic Pricing, Edge-Cloud Computing and LoRa Victor Kathan Sarker 1,* , Tuan Nguyen Gia 1, Imed Ben Dhaou 1,2,3 and Tomi Westerlund 1 1 Department of Future Technologies, University of Turku, 20500 Turku, Finland; tunggi@utu.fi (T.N.G.); imed.bendhaou@utu.fi (I.B.D.); tovewe@utu.fi (T.W.) 2 Department of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, Qassim University, Unaizah 56453-2865, Saudi Arabia 3 Department of Technology, ISIMM, University of Monastir, Monastir 5000, Tunisia * Correspondence: vikasar@utu.fi Received: 9 July 2020; Accepted: 14 August 2020; Published: 19 August 2020 Abstract: A rapidly growing number of vehicles in recent years cause long traffic jams and difficulty in the management of traffic in cities. One of the most significant reasons for increased traffic jams on the road is random parking in unauthorized and non-permitted places. In addition, managing of available parking places cannot achieve the expected reduction in traffic congestion related problems due to mismanagement, lack of real-time parking guidance to the drivers, and general ignorance. As the number of roads, highways and related resources has not increased significantly, a rising need for a smart, dynamic and effective parking solution is observed. Accordingly, with the use of multiple sensors, appropriate communication network and advanced processing capabilities of edge and cloud computing, a smart parking system can help manage parking effectively and make it easier for the vehicle owners. In this paper, we propose a multi-layer architecture for smart parking system consisting of multi-parametric parking slot sensor nodes, latest long-range low-power wireless communication technology and Edge-Cloud computation. -

Print Ebsteins Anomaly Prog

Ebstein’s Anomaly A Comprehensive Approach The Congenital Cardiac Unit Southampton University Hospital Trust 14th & 15th April 2008 Programme Course Organisers Dr Marcus Haw, Southampton General Hospital Dr Nicola Viola, Southampton General Hospital CPD points applied for Tel: 01438 751519 www.cfsevents.co.uk Aim of the meeting: To demonstrate treatment of Ebstein’s Anomaly in 2008 and to stimulate debate on the management of these patients with life long cardiac disease. This meeting is aimed at consultant cardiologists and senior and trainee surgeons involved in the management of patients with Ebstein’s Anomaly. The course is limited to 120 delegates and will be on a first come first served basis. Morphology will be correlated with the latest imaging techniques. Current management will be discussed by world experts and live surgery demonstrated by recognised experts in the field. Sponsors This meeting is sponsored by unrestricted educational grants from the following companies: How to find Southampton General Hospital Heartbeat Education Centre F Level, North Wing, Southampton General Hospital Tremona Road Shirley Southampton SO16 6YD From the car park entrance, face the hospital main entrance and, turning to the left, follow the road around the building to the North Wing (light green and brick building) entrance. The lift and stairs to level F are inside, on your left, at 20 metres. Parking Entrance to the site's main multistorey car park is off Tremona Road. When parking in the multistorey car park, collect your ticket on entry and keep it with you. Please exchange ticket at the reception desk within Heartbeat Education Centre for a subsidised all day car park token which will cost £6:00. -

Bp1 / Llv Impacts + Beyond

BP1 / LLV IMPACTS + BEYOND Games Monitor [ Briefing paper on London 2012 Olympic Games ] Games Monitor, December 2015 (fifth edition) – replacing previous background papers and extensively revised Other papers in the series: BP 2 / Finance, profit + infrastructure BP 3 / Apparatus (state + media) http://www.gamesmonitor.org.uk/contact_media_centre Games Monitor was founded in 2005 to raise awareness on issues around the London 2012 development process. We can be contacted at [email protected]. Questions on the background papers specifically should be addressed to Carolyn Smith [email protected]. CONTENTS 1. Loss of habitat and Common Land 7 1.1 Wildlife casualties and habitat destruction 7 1.2 Loss of Common Land, historic landscape and open space 8 Lammas Lands Exchange land (Hackney Marshes) Greenwich Park Wanstead Flats Leyton Marsh Drapers Field 2. Clearance of settlements, firms and local sport 13 2.1 Population displacements 13 Homelessness Gypsies and Travellers Clays Lane estate Students living on the Park Village estate Carpenters Estate, Stratford Manor Garden allotments River Lea bargees 2.2 International context of residential displacement 19 Erasure of Roma settlements, Athens 2004 Forced removal, Beijing 2008 Gentrification and resistance, Vancouver 2010 Clashes and inadequate infrastructure, Sochi 2014 Repression in the favelas, Rio 2016 2.3 Local economy: displacement of small businesses 23 2.4 Sporting losses and targets 25 Grassroots sport Cycling Football (soccer) Swimming Cuts to sports finance Sports participation 3. Contamination fears and impact of construction 27 3.1 Radioactive contamination and hazardous waste 27 3.2 Air pollution associated with construction 28 3.3 Impacts of construction on local residents 29 3.4 Sewage contamination 29 4. -

Bournemouth Bh2 6Ej

NCP BOURNEMOUTH BH2 6EJ LONG INCOME CAR PARK INVESTMENT LET TO THE 5A1 COVENANT NCP LIMITED FOR A FURTHER 18.2 YEARS. NCP THE SQUARE RICHMOND HILL BOURNEMOUTH BH2 6EJ ENTRANCE EXIT INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS PROPOSAL Prime multi-storey car park located in the very heart of the Large strategic town centre investment providing 236 parking Offers sought in excess of £5,540,000 (Five Million Five popular and affluentcoastal town of Bournemouth spaces arranged over 8 levels with a site area of Hundred and Forty Thousand Pounds) subject to contract Let to the strong covenant of National Car Parks (NCP) approximately 0.48 acres (0.19 Hectares) and exclusive of VAT. This reflects anet initial yield of Limited (5A1) for an unexpired term of 18.2 years Virtual Freehold 5.25%, after allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.63%. Situated adjacent to Bournemouth’s principle retail and Direct Town Centre access from Bournemouth’s main arterial leisure offerings, a short ten minute walk to Bournemouth’s road the A338 beach and pier Based on a purchase at asking terms the property has a very Topped up rent passing of £310,065 pa subject to RPI low capital value of £82.15 psf annual increases (1.5%-5% collar and cap) NCP THE SQUARE RICHMOND HILL BOURNEMOUTH BH2 6EJ LONG INCOME CAR PARK INVESTMENT LET TO THE 5A1 COVENANT NCP FOR A FURTHER 18.2 YEARS A338 BOURNEMOUTH BROMPTON LIBRARY COURT BOURNEMOUTH TOWN HALL SITE AREA: 0.48 Acres (0.19 Hectares) LEVELS: 8 TOTAL SQ FT: 67,436 BOURNEMOUTH CENTRAL GARDENS NATIONWIDE OFFICES THE SQUARE THE BOURNEMOUTH ORATORY BOURNEMOUTH BH2 LOWER GARDENS ST PETER’S CHURCH BOURNEMOUTH BOURNEMOUTH BOURNEMOUTH INTERNATIONAL CENTRE BEACH & PIER PAVILION THEATRE 0.1 MILES SOUTH ▼ 0.2 MILES SOUTH ▼ 0.1 MILES SOUTH ▼ Outline for indicative purposes only. -

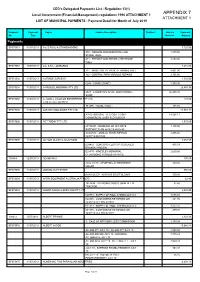

Attach7brf190910.Pdf

CEO's Delegated Payments List - Regulation 13(1) Local Government (Financial Management) regulations 1996 ATTACHMENT 1 APPENDIX 7 ATTACHMENT 1 LIST OF MUNICIPAL PAYMENTS - Payment Detail for Month of July 2019 Payment Payment Payee Invoice Description Contract Invoice Payment No Date Amount Amount Payments EF079951 31/07/2019 A & S PUGLIA STONEMASONS 5,720.00 470 - REMOVE AND REINSTATE LIME 1,870.00 STONE WALL 471 - REPOINT AND REPAIR LIME STONE 3,850.00 WALL EF079058 10/07/2019 A A & R L LOMBARDO 7,216.00 121 - WINDERMERE PARK RETAINING WALL 4,851.00 122 - CENTRAL PARK VARIOUS REPAIRS 2,365.00 EF079592 31/07/2019 A GRADE SURVEYS 1,300.00 6243 - CONSULTANCY 1,300.00 EF079608 31/07/2019 A PROUD LANDMARK PTY LTD 26,450.36 2827 - LANDSCAPE MTCE NORTHSHORE 26,450.36 SUMP EF079658 31/07/2019 A.J AND L.J DALTON ENTERPRISE PTY LTD 178.80 T/AS CLARK RUBBER 781496 - RUBBER MATT 178.80 EF079600 31/07/2019 A2K TECHNOLOGIES PTY LTD 18,568.17 A2KSITQ320506 - AEC COLLECION 18,568.17 COMMERCIAL USER ELD SUBSCR EF079606 31/07/2019 ACT TODAY PTY LTD 4,593.60 20194843 - RENEWAL OF ULTIMATE 1,188.00 SUPPORT PLAN 26/06/19-26/06/20 20200013 - ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION 3,405.60 06/07/19-06/07/20 EF079590 31/07/2019 ACTION GLASS & ALUMINIUM 3,087.59 B24412 - DUNCRAIG LEIS CTR REGLAZED 458.59 BROKEN WINDOW B24475 - KINGSLEY MEMORIAL 2,629.00 CLUBROOMS VARIOUS REPAIRS 108649 12/07/2019 ADAM POAT 300.00 8032 1/7/19 - SPORTING ACHIEVEMENT 300.00 GRANT EF079890 31/07/2019 ADRIAN MUIR SYKES 350.00 INV01/26-EP - RIGGING SCAFFOLDING 350.00 EF079609 31/07/2019 AFGRI EQUIPMENT -

4/01821/18/Ful Temporary Change of Use of Land To

4/01821/18/FUL TEMPORARY CHANGE OF USE OF LAND TO CAR PARK PROVIDING 90 SPACES INCLUDING 6 DISABLED SPACES TO DISCHARGE CONDITION 15i OF PLANNING PERMISSION 4/00122/16/MFA (CONSTRUCTION OF 8 HALF STOREY CAR PARK WITH ASSOCIATED WORK TO PROVIDE 312 SPACES + 15 DISABLED SPACES.) Site Address THE MOOR, MILL STREET, BERKHAMSTED Applicant Dacorum Borough Council, The Forum Case Officer Rachel Marber Referral to Council own scheme- Amendments to design since previous Committee committee approval on the 6th September 2018 1. Recommendation 1.1 That planning permission be Granted. 2. Summary 2.1 The use of the site as a temporary car park would not result in detrimental impact to visual or residential amenity of the immediate area, or highway safety and operation. The low level harm which would result to designated and non-designated heritage assets and loss of open recreational space would be off-set by the long term benefit of the multi-storey car park construction and provision to secure a higher quality public open space once the temporary permission seizes to operate. The proposed development is therefore considered to accordance with the NPPF (2018), Policies NP1, CS1, CS4, CS8, CS10, CS11, CS12, CS25, CS26, CS27, CS29, CS31 of the Core Strategy (2013) and Saved Local Plan Policies (2004) 10, 12, 51, 55, 57, 73, 75, 99, 100, 101, 113, 116, 118, 119, 120 and Appendices 5, 6 and 8. 3. Site Description 3.1 The application site comprises the Moor Recreation Ground which is located to the west side of Mill Street within Berkhamsted Town Centre and is designated as open land. -

Public Forum D C Committee a (Remote) 30 September 2020 @

Development Control Committee A Public Forum D C Committee A (Remote) 30th September 2020 @ 2pm 1. Members of the Development Control Committee A Councillors: Don Alexander (Chair), , Stephen Clarke, Mike Davies, Margaret Hickman, Olly Mead, Steve Smith, Chris Windows (Vice‐Chair) Mark Wright; Sub: Fi Hance, Barry Clark, Hibaq Jama 2. Officers: Zoe Willcox – Director, Development of Place; Gary Collins ‐ Development Management; Laurence Fallon, Matthew Cockburn – Transport Development Management. Development Control Committee A Statements/Petitions/Questions No. Name Application Page Speakers 18/06722/F Land at Little Paradise & Stafford Street Bristol BS3 4DE Q01 Cllr Clive Stevens – Question p.1 S 01 Amanda Tchoc Vegan Café ‐ p3 S As Above 02 George Grace BID Bedminister p.4 S 03 Jo Davis Avison Young p.5 S 04 Zoe Sharpe Dandara p.6 S 05 Darren Jones East Street Fruit Market p.7 S 06 Gareth Jones p.8 07 Dianne James p.9 S 08 Daniel Fryer p.10 09 Matthew Montagu p.11 S 10 Margaret Bartlett p.12 11 Kay Oliver p.13 12 Naomi Berry p.14 13 Helen Adshead p.15 S 14 Louisa Birkin p.16 15 Ross Kirsten p.17 S 16 Roland Oliver p.18 S 17 Aileen McLoughlin p.19 S 18 Andy Kemp p.20 19 Wolfgang Kuchler p.22 S 20 Tessa Fitzjohn p23 S 21 Mr T Kaminer p.24 22 Cllr J Wellington p.25 S 23 Olivia Nava p.26 24 Sean Cork p.27 S 25 Simon Dicken p.28 S 26 Mr C Brockman p.29 27 Cllr Charlie Bolton p.30 S 28 James Jackson p.31 S 29 Tony Dyler p.32 Development Control Committee A 30 Mike Howshall p.33 Continue as above 31 Sally Cavanagh p.34 32 James Young p.35 -

Park Street Car Park Planning Guidance Note

Park Street Car Park Planning Guidance Note joint URBAN DESIGN Marchteam 2016 Front cover picture by Matthew Paul This publication has been produced by: Cambridge City Council Urban Design & Conservation Team PO Box 700 Cambridge CB1 0JH Tel: 01223 457000 This document can be downloaded from www.cambridge.gov.uk Printed on recycled paper. Please recycle. CONTENTS PARK STREET CAR PARK PLANNING GUIDANCE NOTE Contents 1. Introduction and Background 4 1.1. Introduction and Background 4 1.2. Purpose and Scope of the Brief 4 1.3 Site Location, History and Analysis 6 2. Planning and Design Advice 14 2.1 Development Principles 14 2.2 Scale and Massing 14 2.3 Key Views 16 2.4 Finer Grain Development 16 2.5 Rediscovering ‘The Yards’ 16 2.6 Retail Use 16 2.7 Car Park Access 17 2.8 Public Realm 17 2.9 Amenity Space 17 2.10 Activate the Edge 17 2.11 Cycle Provision 17 2.12 Sustainable Development Guidelines 17 2.13 Public Art 18 2.14 Planning Obligations 18 Glossary 19 List of Figures 21 All maps in this document have been reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationary Office © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings (Cambridge City Council Licence No. 100019730 2016) 3 PARK STREET CAR PARK PLANNING GUIDANCE NOTE INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND site through providing clear information 1.1. Introduction and Background on the form of development likely to be 1.1.1. -

Winning Spaces Our Global Portfolio of Sports Projects

WINNING SPACES OUR GLOBAL PORTFOLIO OF SPORTS PROJECTS 1 WINNING SPACES Melbourne Park Redevelopment Eastern Plaza - National Tennis Centre Image courtesy of Major Projects Victoria - Peter Glenane CONTENTS SPORTING PROWESS 04 OUR PROJECTS 06 Community Icons 06 World-class Experiences 26 Flexibility and Innovation 40 Pace and Efficiency 52 OUR SERVICES 66 ABOUT US 68 Cover image Perth Arena courtesy of Cameron Chisholm Nicol and ARM, photographer Greg Hocking 3 WINNING SPACES WINNING SPACES SPORTING PROWESS WE HAVE BEEN A PROUD PLAYER IN GLOBAL SPORTS DEVELOPMENT FOR OVER FOUR DECADES, HELPING CLIENTS ENRICH COMMUNITIES AND STADIA AQUATICS CENTRES VELODROMES TENNIS CLUBS ELECTRIFY AUDIENCES Mercedes Benz Stadium Pan Am / Parapan Am Aquatics Centre Hong Kong Velodrome Melbourne Park Redevelopment Eastern Plaza – Page 30 Page 24 Page 62 National Tennis Centre WITH STRIKING AND Page 64 SUSTAINABLE VENUES. At WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff, we have a long history supporting the creation of diverse sports facilities for a rich array of clients. Our record covers everything from national stadia to school swimming pools, multipurpose arenas to specialist facilities, in a portfolio spanning the world. We bring a global skill set, passion for beautiful buildings and matchless experience to every project, working with architects, owners, councils and developers to create iconic and cost-effective structures that reward both users and operators. EQUESTRIAN CENTRES SPORTS ACCOMMODATION SPORTS CENTRES MULTIPURPOSE ARENAS Al Shaqab Equestrian Centre Commonwealth Games Athletes Village Abbotsford Entertainment & Sports Centre Seattle Arena With an intimate understanding of international Page 28 Page 60 Page 13 Page 23 sports dynamics and creative and flexible teams, we tailor global best practice to meet the needs of every project. -

A New Kind of Bleak. Journeys Through Urban Britain

A NEW KIND OF BLEAK engineeringwithraj engineeringwithraj A NEW KIND OF BLEAK Journeys Through Urban Britain OweN HatHERleY engineeringwithraj London • New York First published by Verso 2012 © Owen Hatherley 2012 All rights reserved The moral rights of the author have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN-13 978-1-84467-857-0 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hatherley, Owen. A new kind of bleak : journeys through urban Britain / Owen Hatherley. -- 1st ed. p. cm. Includesengineeringwithraj bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-84467-857-0 -- ISBN 978-1-84467-909-6 (ebook) 1. Great Britain--Social conditions--21st century. 2. Great Britain--Economic policy--21st century. 3. Great Britain--Politics and government--21st century. I. Title. HN385.5.H38 2012 306.0941--dc23 2012010811 Typeset in Fournier by MJ Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed by ScandBook AB in Sweden …We wanted something new, and we Would sacrifice most anything (Well, decorum definitely) To get our gawky, sky-jostling Ruck with nature set in knifey Portland stone. Of course, I know Time hasn’t widened out the way We reckoned all those years ago. You plan for that, allow for that. I know the building might have housed The odd careerist democrat Or two, and yes, we missed Our chance to make a truly ideal Hive, a fair organic whole. -

Cladmag 2016 Issue 1

2016 ISSUE 1 CLADGLOBAL.COM mag @CLADGLOBAL FOR LEISURE ARCHITECTS, DESIGNERS, INVESTORS & DEVELOPERS Elora Hardy & Ewe-Jin Low The Green School designers taking on Powder the resort market Mountain Chad Crowd-funded resort Oppenheim taking shape in Utah Balancing fantasy and functionality Zaha Hadid Messner Mountain Museum Corones FRANCINE HOUBEN Designing for unpredictable change WORLD’S H TTEST SAUNA DESIGNS http://www.gocohospitality.com ArenaVision LED Enabling new experiences at sports venues Philips ArenaVision LED system – a new innovative LED pitch lighting solution supporting the latest TV broadcast standards and, thanks to a dedicated control platform, creating a complete immersive experience. Designed exclusively for televised high-end sports and multifunctional lighting applications, fulfilling all contemporary and future field-of-play requirements i.e. light level, uniformity, glare rating, super slow motion broadcasting, ArenaVision LED offers outstanding light quality, effective thermal management, and a very long lifespan. Philips ArenaVision Floodlighting System http://www.philips.co.uk/outdoorlightingwww.philips.co.uk/outdoorlighting EDITOR’S LETTER Children in Japan are helping design the cities of the future. This needs to happen everywhere Seen and heard Japan has embraced UNESCO’s Child Friendly Cities initiative and is involving children in decision-making around design, architecture and urban planning, setting an example for others to follow in both the developed and the developing world he UNESCO Child Friendly Cities initiative, which was founded in 1996, has been enthusiastically adopted by cities in Japan. The initiative was conceived as a T way of empowering children and implementing the Convention on the Rights of the Child at a local level.